Digital Art: Beyond The Hype

- Words

- Charmaine Li

If you think of the term ‘digital art’, you might conjure up images of twitchy GIFs or glitchy videos. You might think it’s a recent development, but in fact its practice has roots dating back to the 1960s. So – what is considered ‘digital art’? And why are people paying for it? Is it all just hype? We delved into this topic and spoke to some key artists and gallerists about what it means to create, consume and sell digital art…

While digital technologies touch on almost every aspect of our lives, digital art belonged predominantly to hacktivists and nerds until recently. Now, it’s a phenomenon attracting growing interest and examination from the mainstream art world and general public. In 2014, Google announced a global initiative, dubbed ‘DevArt’, with the aim of inspiring coders and artists to further delve into how technology and creativity intersect. A year before that, the Tate also unveiled the IK Prize, an annual award for digital artwork ideas.

Left: Daniel Temkin, Glitchometry Circles #4, (2013) Right:Joe Winograd for 15folds, GIF Sculpture VII, (2015) Bottom:Mark Dorf, //_path/untitled21

And yet, the fuzzy space where art and new media/technology intersect remains marginalized and mysterious. It seems there are multiple perspectives and no clear answers, but perhaps it’s less about those things and more about paying attention to how people create, consider, experience and respond to digital art.

CREATING & CONSUMING

A significant amount of digital art is created for and consumed online where each image can be easily seen, reproduced and adapted into the context of your own life. Unlike staring at a framed painting in a gallery, experiencing digital art might mean watching a video of an interactive installation that was uploaded on Instagram. Or it might involve staring at a GIF on Tumblr among countless open tabs while Drake is blasting on Spotify. The speed at which images can now be replicated, reused and altered means we’re inundated by more information and imagery than ever before. So is this broadening or narrowing our experience of art?

Top: Matthew DiVito, new_ideas (2012) Left:Mark Dorf, //_path/untitled37 Right:Matthew DiVito, trigon (2012)

Last year, ‘Ways of Something’ – a project by Canadian artist Lorna Mills – garnered the number one spot for Artnet’s Top 10 digital artworks of 2014. For the piece, Mills compiled and curated a remake of John Berger’s influential BBC documentary Ways of Seeing (1972), which delved into how we look at images and consume visual culture. To produce the four-episode project, Mills invited more than 115 artists to contribute one-minute segments to depict art-making after the Internet. The result was a cacophony of visuals ranging from 3D renderings, GIFs and web cam performances.

Mills, who makes a living predominantly working on children’s software and games, has also been creating GIF art since the early 2000s. In an interview, she told us she’s particularly drawn to imagery relating to Internet filth, cross-species romance and people playing with blow-up toys. When asked about her creative process in GIF-making, she responded, “I spend many hours online each day looking at GIFs. I look at the open-source stuff, on Reddit and a bunch of Russian GIF sites – and collect it all. I don’t use everything, but I have a huge collection. After that, it’s editing down the ones that appeal to me and that I think I can work with. It’s very intuitive… I go where my eyes take me.”

Giselle Zatonyl, Ways of Something, Episode 1, Minute #22

Like digital art, the GIF dates further back then most would expect. The invention of the GIF—also known as ‘graphics interchange format’—traces back to 1987, when a CompuServe employee named Steve Wilhite debuted the file format. In the past decade, GIFs have had an immeasurable influence on the way we present imagery, spread news and interact with each other on the Web.

For a group of three UK-based creatives, including Margot Bowman, Sean Frank and Jolyon Varley, the format inspired them to start a digital art project called 15folds in 2012 with the aim of elevating the status of GIFs as an art form. In the past decade, GIFs have had an immeasurable influence on the way we present imagery… Each month, 15folds selects a theme, such as democracy and migration, and creates a GIF on the topic. Then the team commissions a set of 14 artists to respond to the theme with a GIF. The result is an online ‘show’ that consists of a chain of strange and beautiful works displayed on a clever Tumblr site built by Varley’s startup company.

“Previously, with a lot of visual art forms, it was quite a niche means of expression and you had to be highly technically skilled to interact in the medium. What we really liked about GIFs and the reason why we started using the format was because it was a way to make something that was totally digital as a non-developer and non-coder,” explained Bowman in an interview.

However, the trio weren’t satisfied with leaving the GIF inside the browser and in May 2014 they hosted a real-life GIF exhibition in London that required viewers to download an app on their phone in order to access the artworks. “We’ve been frustrated in the past as to how GIFs have been exhibited in gallery spaces – they were always on TV screens or projectors. You’d end up burning your GIF as a movie file to a DVD and just putting out on loop,” Frank pointed out, “And we didn’t think that was pure to the GIF art form, which was made for the Internet.” Instead, the three members decided to hang custom QR codes on gallery walls and asked viewers to scan it with their phones in order to see the GIFs to maintain the Internet element.

A more classical instance of the GIF making its way to the gallery space is the latest exhibition at Berlin’s DAM Gallery titled ‘DRKRM’. The familiar white cube is transformed into a darkroom where GIFs by artists, such as Kim Asendorf and Olia Lialina, are displayed through projections and screens. Established in 2003 by Wolf Lieser, DAM Gallery represents a range of artists using digital media in their work. “…transferring digital aesthetics or representational aspects to I is a common trait of the ‘post-Internet’ generation.” Bringing a format that only exists online to a brick-and-mortar space may sound strange to some, but Lieser insists that transferring digital aesthetics or representational aspects to IRL (In Real Life) is a common trait of the ‘post-Internet’ generation.

An example of this kind of digital art is Asymmetric Love (2013) by American artist Addie Wagenknecht. For the sculpture, she used steel, CCTV cameras and DSL Internet cables to create a form that mimics a baroque chandelier. By repurposing the CCTV equipment into a familiar object, Wagenknecht wanted to reflect on our current digital infrastructure and how surveillance has become so deeply entrenched into everyday life that it is often overlooked as a threat.

Left: Addie Wagenknecht, Asymmetrical Love (2013) Right: Matthew DiVito, Rough Seas (2012) Bottom: Andreas Nicolas Fischer, Schwarm (2015)

While usage of ‘post-Internet’ has been floating around since the mid-2000s, only recently did the ambiguous term seep into the mainstream. “Post-Internet is an interesting development,” explained Lieser, “The term was coined by Marisa Olson, an artist from New York, and it didn’t mean ‘after’ the Internet, rather it referred to artists to whom the Internet was something normal and not unusual anymore… It’s really a trend in contemporary art.”

Discussions on what post-Internet encapsulates and how it relates to other artists who have been using emergent technologies in the past have appeared from contemporary art publications like Frieze to Elephant Mag.

While there’s still no definitive description of what it is, the term often alludes to the practice of creating art shaped by the ubiquity of the Internet and its impact on culture.

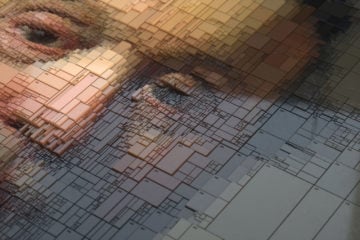

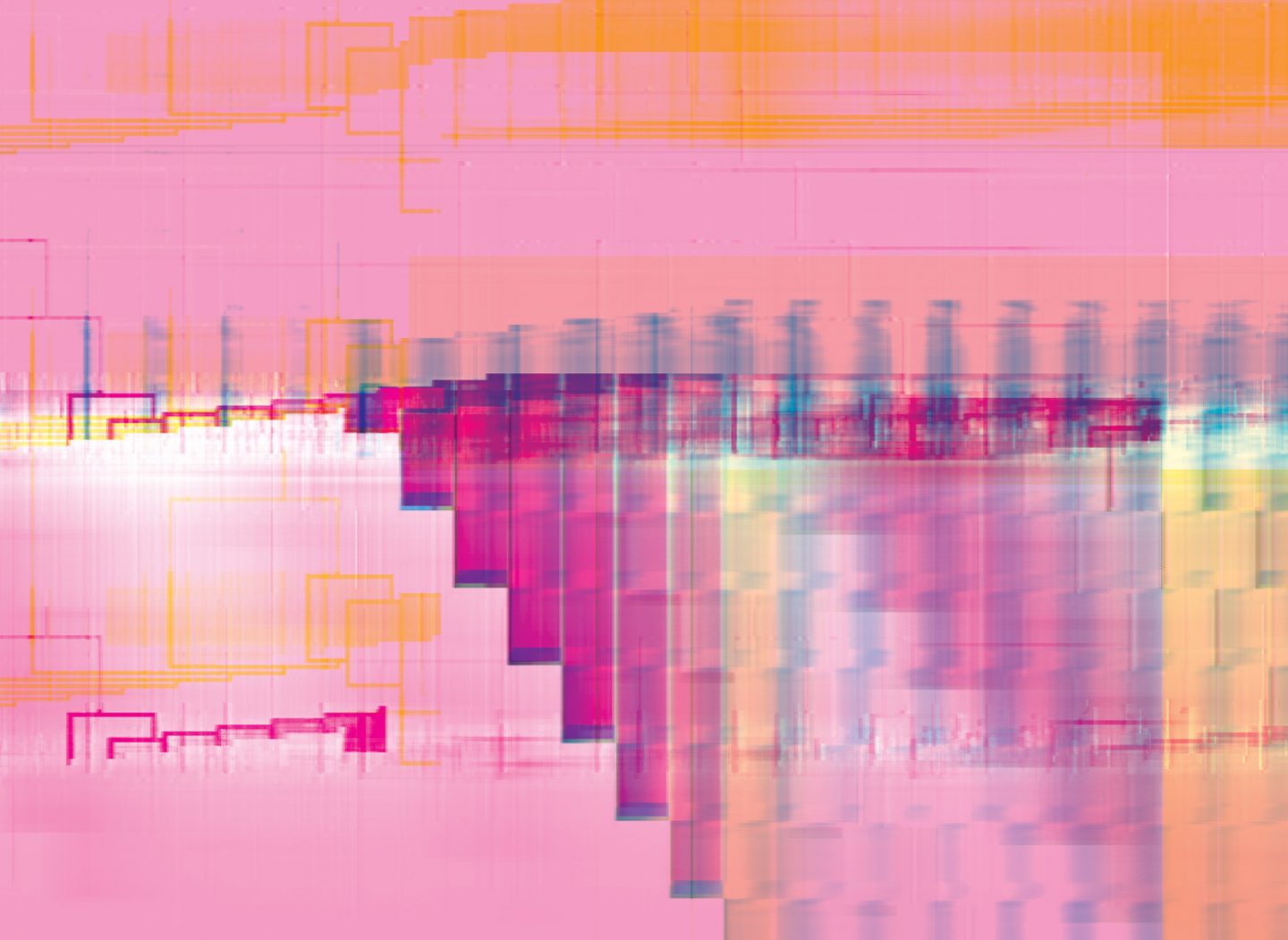

Berlin-based artist Andreas Nicolas Fischer would fit the bill. For Schwarm (Software I) (2012), he developed a custom software that creates an ever-changing abstract composition in real-time – a snippet of the piece in action can be seen above in this article’s header section. Essentially, the software analyzes a sequence of photographs and uses their color value data to create a swarm of color that spreads like a paintbrush on a canvas, randomly. The resulting images have also become part of a print series of the same name.

Even though post-Internet art may be hyped up at the moment, Lieser believes the movement is fairly removed from the origins of digital art in the 1960s. When we visited him in Berlin a couple of months ago, DAM Gallery was featuring its ‘Aesthetica‘ show which highlighted works form the early days of computer-based art.

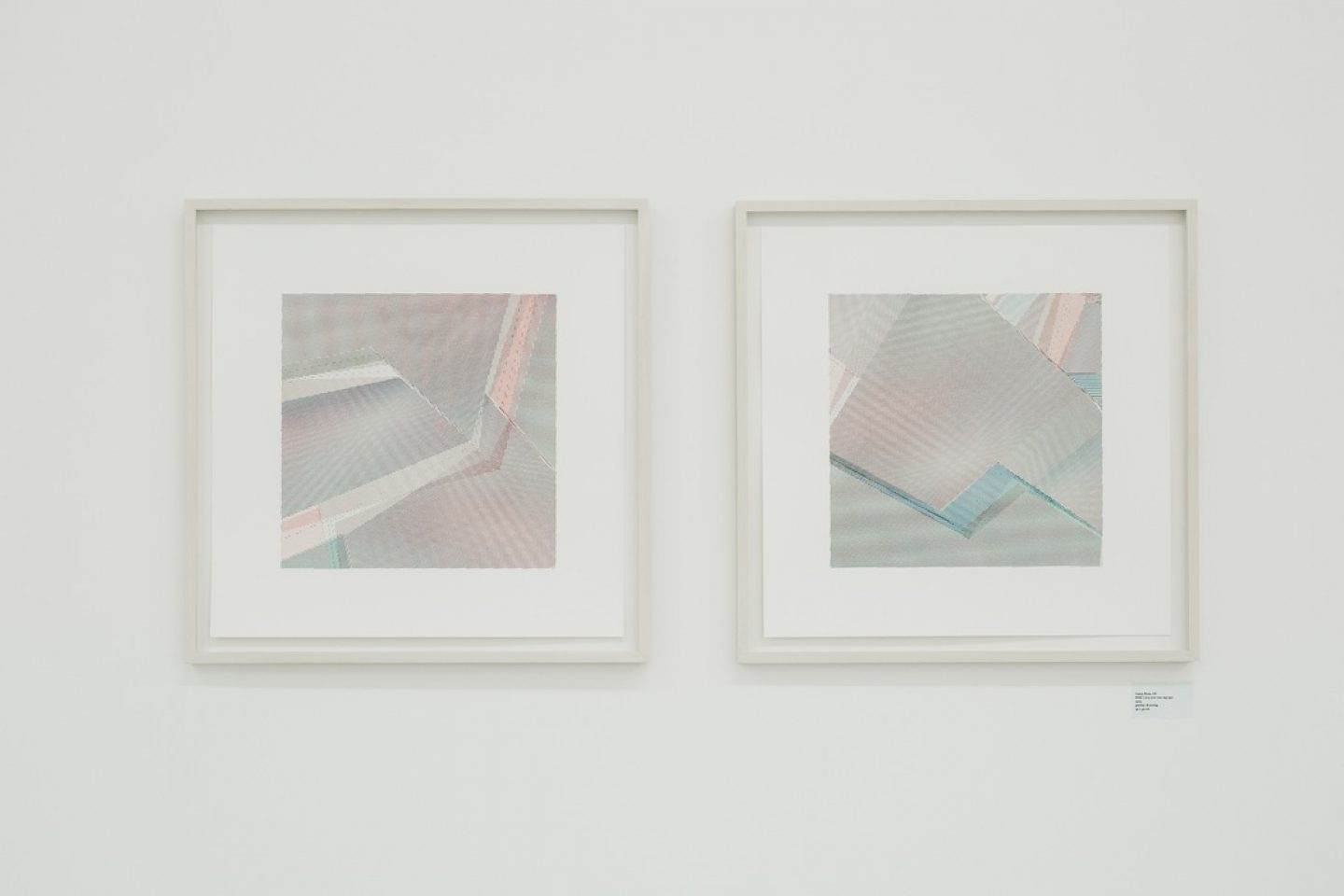

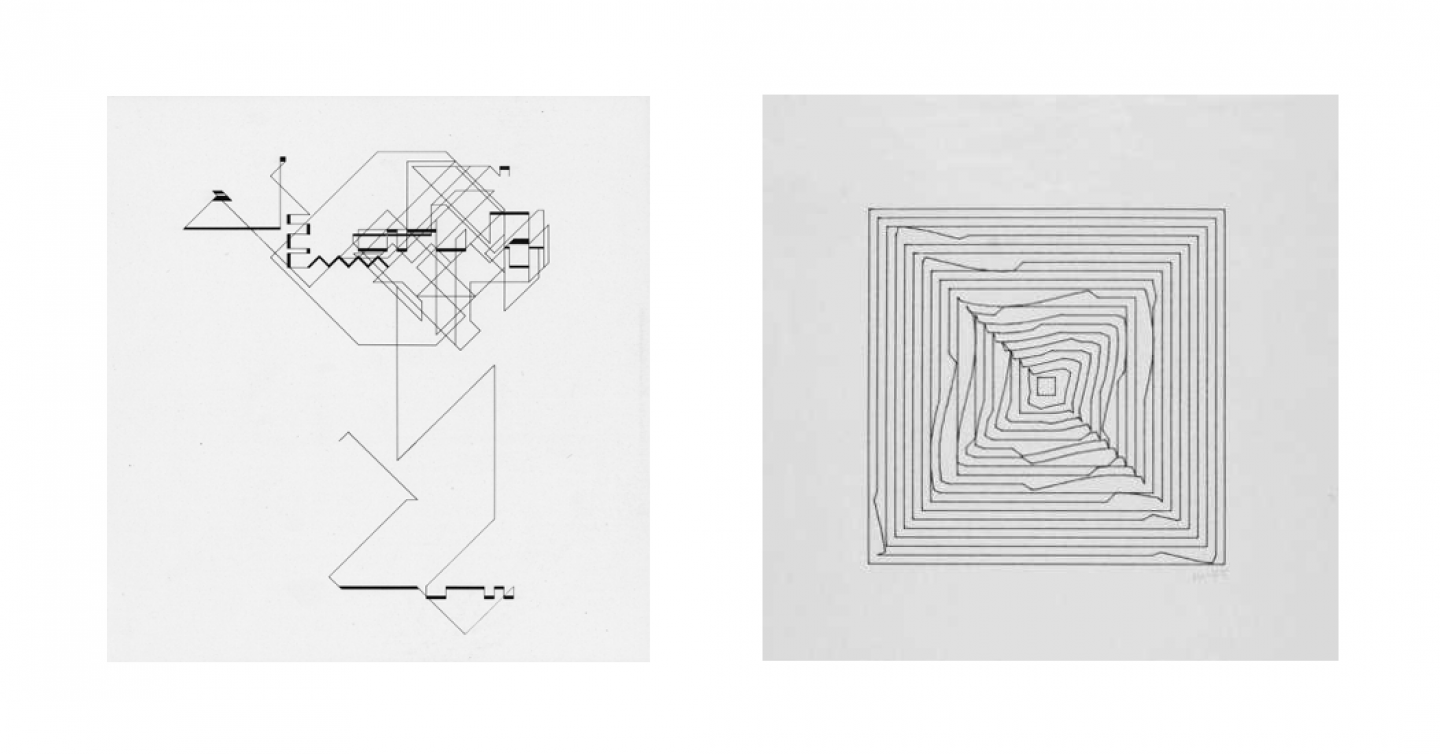

Left: Manfred Mohr, P-18 Random Walk (1969) Right: Vera Molnar, Hypertransformations, variations (1975/76) Courtesy of the artists and DAM Gallery, Berlin.

“People who started working with the computer had to learn to program,” said Lieser, “I’m very interested in artists using programming as a tool, based on this concept of having a rationalized idea. Because when you program, you can’t just have two bottles of wine and then have a wonderful piece suddenly on the screen. “when you program, you can’t just have two bottles of wine and then have a wonderful piece suddenly on the screen” It’s a totally different attitude, you have to refine your concept, define it and put it into programming language, and if you’re lucky it looks good in the end.”

In the middle of the exhibition stood a huge cumbersome gray machine. On loan from the German Museum of Technology in Berlin, the obsolete-looking device built in 1965 is an example of the types of devices artists would use to produce art at the time. To create the plotter drawings hanging in the gallery space, pioneers of this genre—such as Vera Molnar and Manfred Mohr—had to transfer their custom programs to punch cards, which were fed into the computer. The resulting paper strip contained the final processing instructions that would be executed by the pen plotter to produce a drawing typically featuring patterns and geometric forms.

Photos by Ana Santl

Despite the history of digital art, it’s taken museums and art galleries a long time to take this realm seriously and acknowledge it as worthwhile.

BUYING & SELLING

In a world where downloading GIFs and images is free, what does it even mean to own digital art? For many people, the commercial potential of art that’s created and displayed on a screen remains hazy, especially since the traditional art market often relies on the exclusivity of a work to determine its price. In 2014, an artist tried to sell a GIF for $5800 – to no avail.

But perhaps the tide is beginning to turn. In 2013, an auction dedicated only to digital art took place – the first of its kind hosted by international auction house Phillips in collaboration with Tumblr.It seems collectors are increasingly becoming comfortable shelling out five-figures. Software artist Casey Reas sold an animation, Americans! (2013), for $11,000 while the highest bid went to Addie Wagenknecht’s sculpture made of security cameras, Asymmetric Love Number 2 (2013), for $16,000. In total, the auction raised $90,600 – a small fraction of what traditional media like painting and sculpture go for. In one evening earlier this month, New York-headquartered auction house Sotheby’s made sales totalling $294 million, including a “blackboard painting” by artist Cy Twombly that went for a record-setting $70.5 million. Even if digital artworks haven’t reached that stage yet, it seems collectors are increasingly becoming comfortable shelling out five-figures.

As for the nitty gritty of actually selling and delivering a GIF to the buyer, Canadian artist Mills says of her latest exhibition: “They [the buyers] will get the animated GIF file and also get an mp4 of the GIF on a small tablet for a small archive and something to stick on the wall to look at right away.” In the past, it was her dealer who put the GIF file on a flash drive – a low-res version for the Internet and a high-res version for the screen.

Top: Taylor Ervin for 15folds, Three Halves (2015) Left: Daniel Temkin, Glitchometry #20 (2012) Right: Matthew DiVito, Temple (2012)

One of the most contentious issues for a working digital artist is retaining ownership of a piece, while one of the most important considerations for a buyer is an artwork’s authenticity and potential value. When discussing this topic with Lieser at his gallery in Berlin, he explained, “When you buy it [a digital artwork], you receive a kind of documentation, a certificate which is signed and says which number and what edition it is – and you own this piece and this limited number.”

In theory, digital-based artworks shared online by artists—with the intention of exposure—can be easily copied and endlessly reproducible.

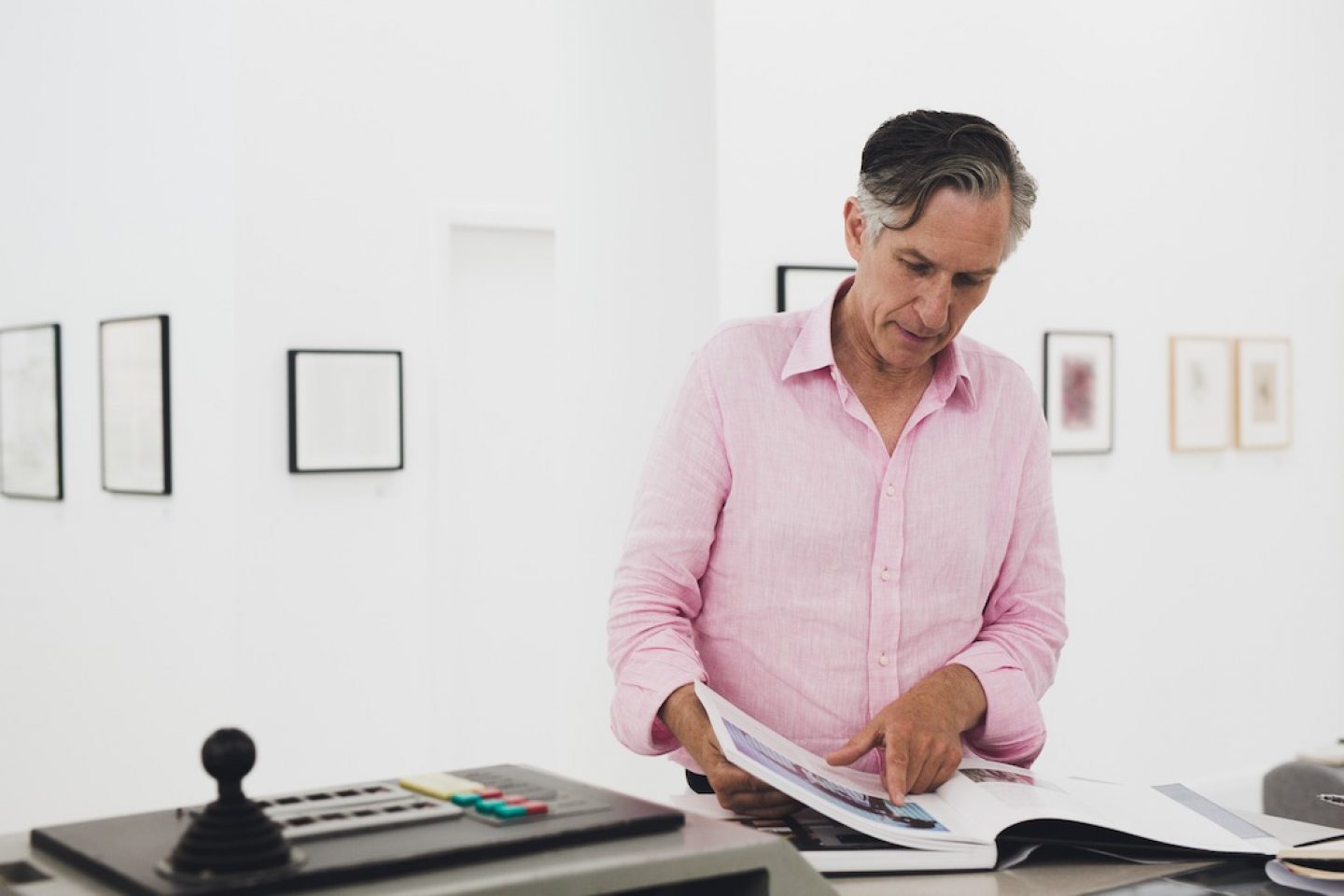

One company tackling this area is Sedition. Launched in 2011 by art world heavyweights Harry Blain (of Blain|Southern) and Robert Norton (former CEO of Saatchi Online), Sedition is an online platform and marketplace for limited edition digital artworks created by contemporary artists ranging from Jenny Holzer and Wim Wenders to Claudia Hart and Mark Dorf.

“The idea for Sedition was to make the best of contemporary art accessible to an audience who are traditionally priced out of that market,” Rory Blain, director at Sedition and brother of Harry Blain, told us. Priced between €7 to €1491, pieces on the platform are either digital editions by established artists anchored to a physical work or artworks made “purely for the digital medium”. Sedition shares a 50/50 cut of the revenue with the artist.

Ryan Whittier Hale, Stone Clouds, 2015 Courtesy of Sedition.

Once an artwork is purchased, it’s delivered to a personal online vault, along an artist-signed certificate of authenticity, where it can be viewed on the web, mobile, tablet or connected TVs/projectors through Sedition’s app or site. “The idea behind that was to keep things in the digital domain,” added Blain, “The artists were really keen that works crafted for a digital display were viewed and displayed digitally.”

With the rise of e-books and online music streaming, it’ll be interesting to see whether art can also make a successful transition to the digital space… and whether digital art can create a big enough IRL demand.

When we asked Blain – who worked at many galleries before starting his position at Sedition – about how he envisions digital art evolving in the next couple of years, he said he had no idea. What he did know, though, was this: “This year is going to be a watershed year for digital art. When people were first starting out with it, they were toying with it at arm’s length and trying to get used to it. Whereas now most of the mainstream has been embracing it and it’s also been set up for mainstream art consumption – online, on-screen or projection… The idea of digital is no longer mysterious.”

Header video by Andreas Nicolas Fischer, Text by Charmaine Li