London Cloth Company Revives The Lost Craft Of Loom Weaving

- Name

- Daniel Harris

- Project

- London Cloth Company

- Images

- Owen Richards

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

From the rescue of a rusting loom in a Welsh barn to 41 tons of machinery weaving endless yards of fabric for export around the globe, the story of the London Cloth Company is a captivating tribute to the hard work, vision and determination of the gregarious Daniel Harris.

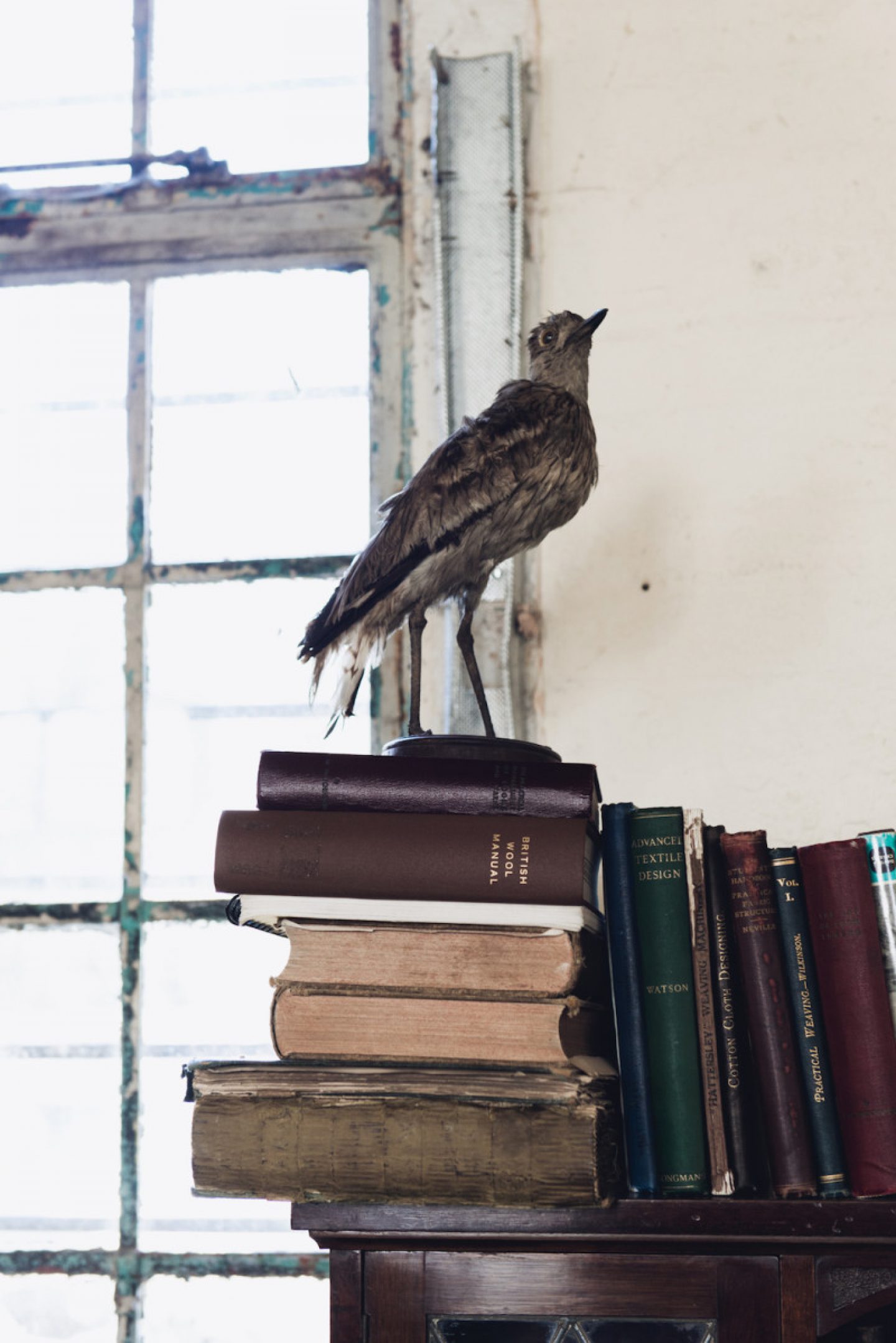

Accompanied by his cat, Flo Rida, in his workshop—located in an old air force hangar on an industrial estate in Epping, London – Harris spent a chilly but sun-dappled morning introducing us to his world of weaving with the industrial machinery he single-handedly rescued and restored.

The London Cloth Co is the city’s first micro-mill. How did it all begin?

“I started off with one loom, and now I’ve got 41 tonnes or machinery, at least. This isn’t even all of it.”I started off with one loom, and now I’ve got 41 tonnes or machinery, at least. This isn’t even all of it. See that black one over there [points] – I was buying something else, and they said, “If you don’t take that one too, we’re going to smash it up.” It’s from an 1880s mill, so I had to rescue it. All the stuff I didn’t take, I had to watch them destroy. It was pretty crushing. The ceiling had caved in on it, and I had to get it out with a winch. I’ve reconfigured all of them. I’ve got another one of these in bits, a whole one in pieces. One’s in a place called Peebles in Scotland, another two are in Langham – they’re in storage, just waiting. I’ve got a cone winder in north Wales, three more of those little looms in Preston.

Originally, I had to go all over the place looking for them and talking to people, but now what happens is that you have northerners who are cleaning out their sheds, and say “Well, we could call up the scrap man to come and take it away and pay him for it. But oh, let’s not do that – let’s get Danny Harris to come and take it away. And he’ll give us money for it.” They can see me coming. It’s quite entertaining.

What was the turning point at which you realized you wanted to turn your passion for weaving into a business?

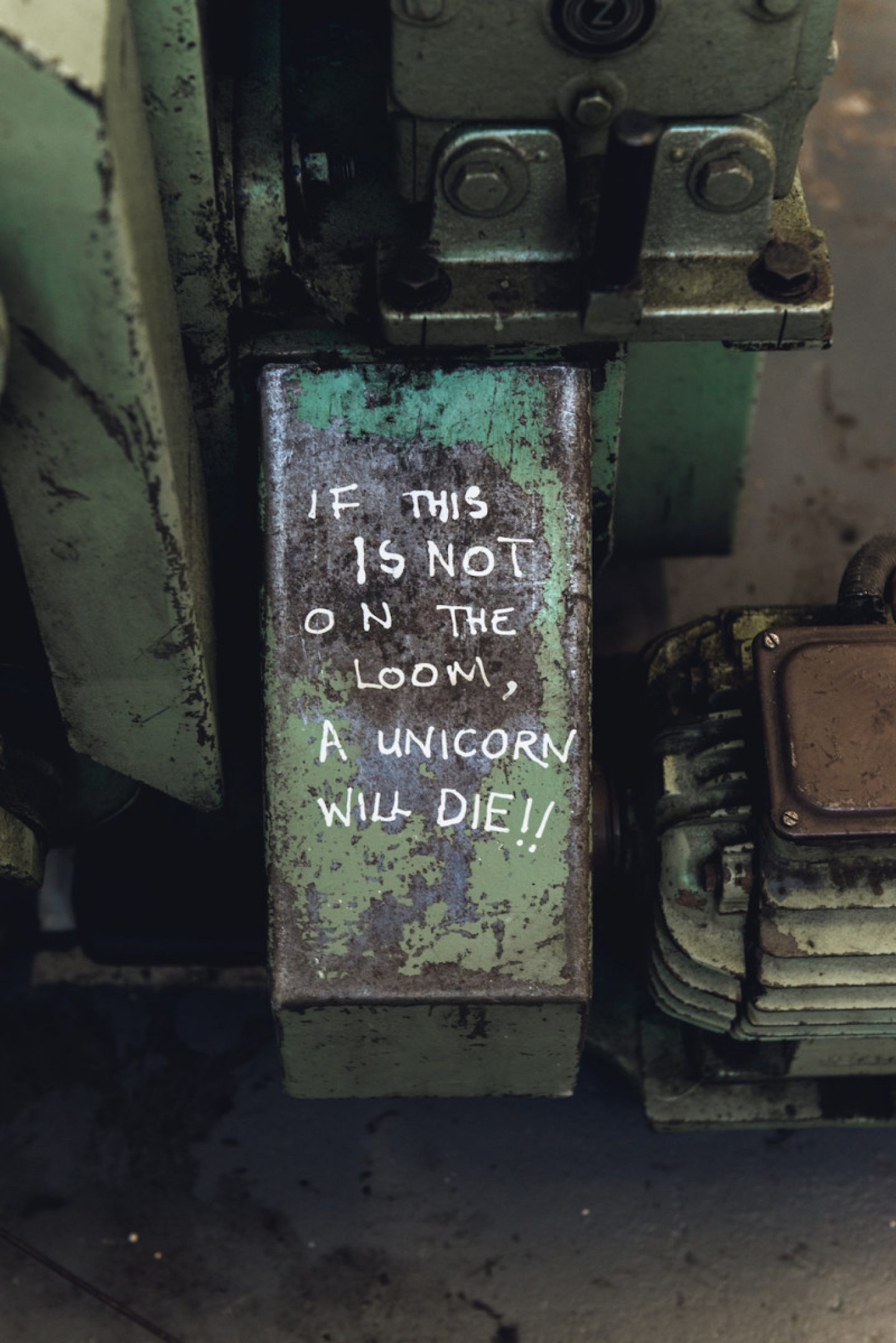

I got the first loom, and I didn’t even do a Facebook page for the first year. I didn’t tell anyone until we’d sort of gotten the hang of it, because that would have been really stupid. I mean – you can have a disaster with anything, but when you have a disaster with this, it is spectacular. I mean, it’s limb-renderingly spectacular. So knew there would be a business in it somewhere, but I didn’t know it would be this one. I mean, to have accumulated this much stuff in what is comparatively a short space of time – it’s quite mental. We’re now looking into whether we could go back to sewing a bit. Doing a small amount of clothes. But we’ll have to wait till we’ve got all this production out of the way again.

You learned how to reassemble rescued mills with no prior knowledge of weaving. How did you go about teaching yourself what you had to know?

“There is a vision—quite a grand vision in the end. I want to build my own mill next.”I started out with the little ones. Then I moved on to a bigger one, and took it to bits. And put it together again. Then after that, I bought three more. [Points to two mills.] These came out of the same mill. They were side by side. There’s one from 1956. It hadn’t run for 14 years, but all we had to do once we got it in here was replace the leather straps, wire it up, and off it went. This one, right next to it, was destroyed. It had two different users. With modern machinery, you have as few moving parts in contact with each other as possible. With this, everything is in contact with everything, and it’s all moving at once. In the first place, it was probably badly put together, and the [previous owners] didn’t look after it properly. The loom actually wasn’t that old – from the late 1960s. We then had to put an entire 1930s loom into this one to make it work. It was ridiculous. But now I’ve woven thousands of meters of fabric on it. And tomorrow it’s being picked up to go to a museum in South Wales. It’ll be used—but in a museum context—they’ll probably only put it on for half an hour a day or so.

When you acquire new piece of equipment, do you have a vision for what you want to do with it, and how it fits into the rest of your workspace?

The essentials are all here. We can make pretty much anything here now. There’s always more things you can do, constantly. There is a vision – quite a grand vision in the end. I want to build my own mill next. Problem is – and this is why we’ve had to move out this far – when you think we were 12 mins from Liverpool Street now – there’s just no room in London now. No place for anything creative. It’s very depressing. So we got this —a 10-year lease on it—but you outgrow it almost immediately. So—believe it or not—you can build an industrial building for dirt cheap, 50 grand, it’s the land that costs you a lot. So we will endeavour to do that. But this year’s all about consolidating. Moving here, setting up. Last year was truly horrible, we had a whole mill all set up [in Hackney, East London]. Then we had to take it all apart, bring it here, put it all back together. It was truly horrible.

You work with a range of clients from small British heritage brands to designers like Ralph Lauren. Can you share with us the creative process when taking on a new brief?

People can be so pretentious, and have such airs about them, like ‘oh, I’m a designer!’, when really, you’re just making things up. So our creation process is very flexible, very easy. For example, you can weave two cloths simultaneously on this machine. There’s the cloth that’s going to be on the surface, but then we draw the white through to make a complicated white check. We can put a completely perfect white square in the middle of that red check, right where we want it. So you’ll have one side which is heavy color, and a bit of white, and the other side will be mainly white with a bit of color.

We’ve also done a range of incredibly expensive dog coats. What I’ve done here—we’ve got the pattern sorted out. We have a plain weave, then a twill, then herringbone, then back to the twill, but with a darker stripe through it. There’s a huge amount of variation we can get within this.

“That yarn over there, there’s only 50 meters of cloth on that beam, but that’s 2,500 pounds worth of yarn. So you don’t want to get it wrong.”We do lots of different types of development for different things. We just designed an entire range of 60 different fabrics for a mill in China. We can weave anything. But the only way to make it work is to say, well, this is how we do it, and stick to it. Every time you go off-piste, it goes wrong. Just throwing the money down the toilet. This is a two-ply super soft. In the past, we tried using a single, and these looms just won’t weave it. In a way, you have to stick to what you know, then slowly do a bit more, and then a little more, without taking too much on. For example. That yarn over there, there’s only 50 meters of cloth on that beam, but that’s 2,500 pounds worth of yarn. So you don’t want to get it wrong.

Can you tell us more about the process of creating a fabric, from brief to completion?

I used to work in sewing for film and TV, and with that, it was great, because someone would say, ‘I need a jacket in three days’. And you can do it, because you can stay up all day and all night to get it done. With this, it takes as long as it takes, and you can’t speed it up. You say, OK – we want to weave this check fabric over here – so you phone up and order the yarn, which might take two or three weeks to arrive—if it’s in stock.

So then you can start preparing in advance, and then you get it all ready, so you walk it all, get it on to the loom, tie it all in to the loom—there’s a day—then start weaving – a couple more days. Then you take it off the loom, darn it, get it off to the finishers – everything has to be washed when we’ve woven it. So it’s gone for another three weeks. So what they all then do is leave it. They say, yeah, we really want that fabric – but we haven’t got it in stock. So we did tell you this – remember, in all those meetings? Oh, but we thought you could get it done in two weeks. The bare minimum is two weeks. And that’s if everything goes to plan. So we quote 6-12 weeks—which is quite a huge variation, really!

We work with the artist and designer Martino Gamper a lot, and recently we did a fun one together. We put a white warp on that loom, and he just painted the back while it was weaving. It went up on the ceiling of a restaurant, The Marksman, on Hackney Road. That was really cool.

What are you working on at the moment?

We’ve just done some stuff for Radley at the moment, which is pretty cool. I’ve been doing this for five years, and have a really strong archive now. So clients might order something we’ve done in the past, but maybe change it a bit. We just did that for Radley, which is completely different to most of what we do, 70% of which is actually indigo. Like denims. It’s Rope-died cotton, and we have 63 different types. We just shipped 1,000 meters to Japan. Like selling coal to Newcastle. They have so much indigo in Japan, yet they still buy it off us. We do a lot of that, and it’s all this sort of thing. We’re the only ones that do this. And then the wool—it’s all about pattern, whereas indigo is all about structure—the wool is generally more made-to-order. It’s a very expensive way of working. For a double cloth, you’re using twice as much cloth and it takes twice as long to weave it. But that’s why a lot of people don’t do it.

You’ve grown the business so fast in such a short amount of time. What’s next for London Cloth Company?

There are so many tiers of plan. Unless we could get a massive cash injection—like winning the lottery—once you’re in here weaving, it’s hard to move forward, so we need to find a way to take things to the next level. But the ultimate thing would be to have our own mill. Before I did this, I did sewing for eight years. I could sew you under the table. The jackets here (points) I pattern cut all those, I sewed all those. We now have a factory who does them for us. So to have a completely vertical operation would be the dream. There’s only one company in the world who does that at the moment—Pendleton. They’ve gone a bit all Navajo, which isn’t really my thing – though generally I like their stuff.

So to do that would be amazing, though I’d be spreading myself a little thin. It would be nice to start doing a lot more retail, because the brand work is a lot to take on when there’s only one or two of you. And you have to deliver on time. We have to take care of all the export. It would be quite nice to still do the brand work, but do more retail, and build this other mill. [Pauses.] Wow, this is huge! It’s like a lifetime’s work. There’s so much stuff to do. And all the day-to-day stuff. The bespoke stuff is really nice to do. It’s not actually the most lucrative. It takes a huge time to set up. The weaving itself is actually very quick. This year it would be really nice to work towards that, going vertical.

"So to have a completely vertical operation would be the dream."

This interview was edited and condensed. All images © Owen Richards