Behind The Bouroullec Brothers’ Samsung Serif Design

- Name

- Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec · Samsung

- Project

- Samsung Serif TV

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Bouroullec is a name that needs no introduction. Ronan and Erwan, the duo of brothers that bears it, are amongst the most prolific designers of their generation, renowned for their considered aesthetic and extensive output.

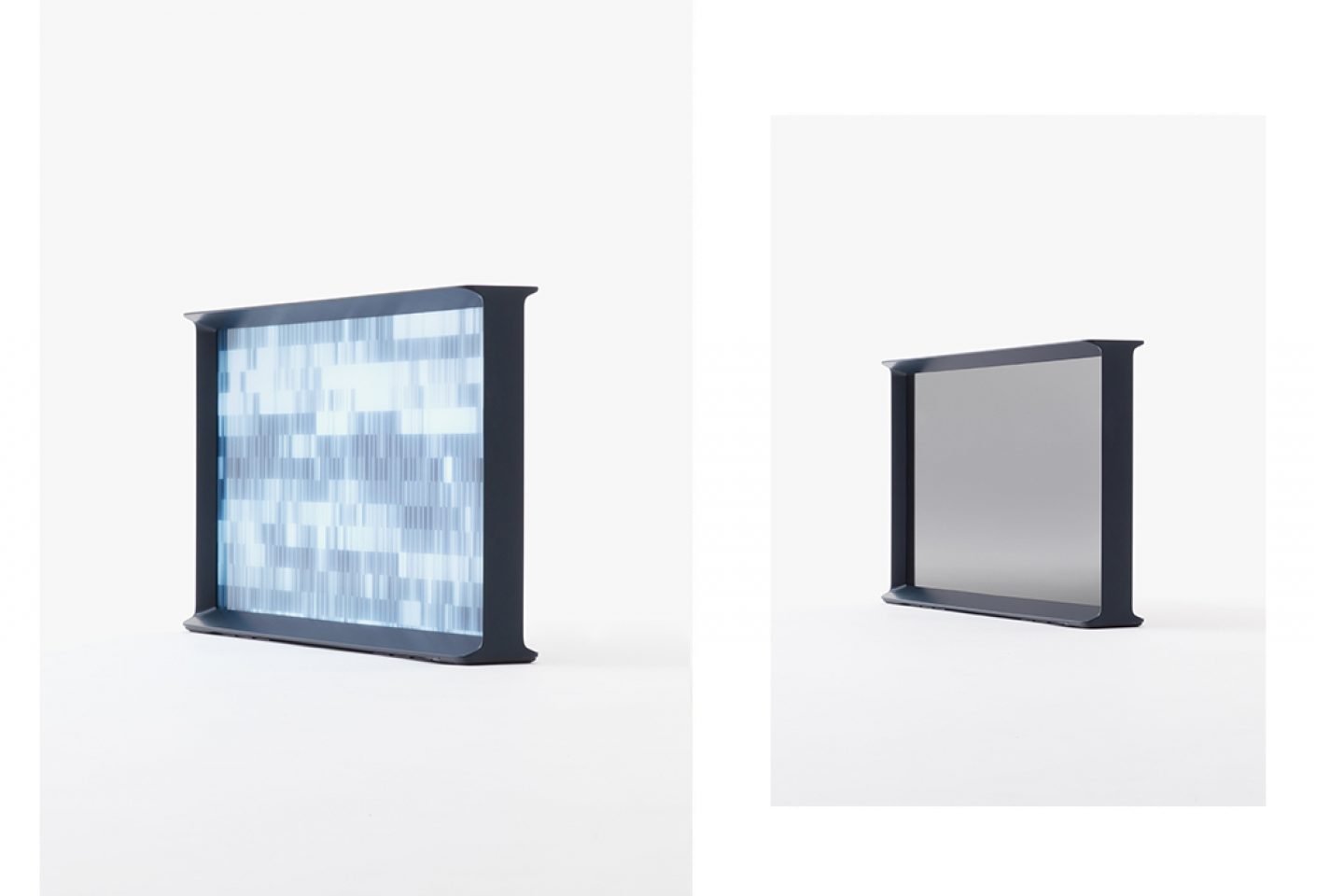

Their Paris-based studio of eight has applied their refined design philosophy to everything from jewelry to architecture, in collaborated with the design industry’s biggest names. One of their latest projects saw them join forces with Samsung to create the Serif – a sleek, subtly-designed television intended to seamlessly fit into everyday life. We had the chance to catch up with Erwan Bouroullec to delve deeper into what it’s like to work in a sibling team, his appreciation for typographic design, and the design process behind the creation of the Serif.

Your brother started his own design studio in the mid-nineties. And you joined him after your studies at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts in Cergy-Pontoise. Can you briefly tell us how you started working together?

“What’s rewarding is the simple pleasure of seeing our work in an everyday context.”I can’t really pinpoint the first time we started working together, but when I was studying art, I came to help Ronan in his studio as I had some free time, and I was happy to use it to experiment and explore. Ronan and I are five years apart in age, so we never had the same friend group, never studied at the same school. We were always together, of course, but there was enough distance between us so that we could learn and live – not totally differently, but not like twins either. One of the motifs of design in general is collaboration, and right now we feel like our relationship is based on discussing our points of view.

Basically, you’re a family business. Isn’t it challenging at times to work together with your brother?

I think the more challenging aspect is that at we pour so much of ourselves into our work. As we are brothers, we even sometimes find it difficult to know exactly who we are, because it looks like we’ve always been together, always been building things together. What’s rewarding, though – I think – is the simple pleasure of seeing our work in an everyday context. Like going to a friend’s house and seeing the furniture we’ve made, and how they live with it.

Do you also work together on client projects or do you split up your workflow completely?

Well, the first thing that is quite important to understand with our studio is that we really are super independent. The main income of our studio comes from royalties from some of the products we made early on. So we don’t need to earn money from present projects, which means we can be super independent, and allows us to make choices that are driven by desire. When we work with a company, it’s because we really want to. Ronan and I are quite hard on ourselves – we’re constantly questioning, also within the context of the studio. It’s always bubbling with energy – positive and negative at the same time. Some projects can go quick, but some can take quite some time. But we always start is with discussion. What we could do, who they are, etcetera.

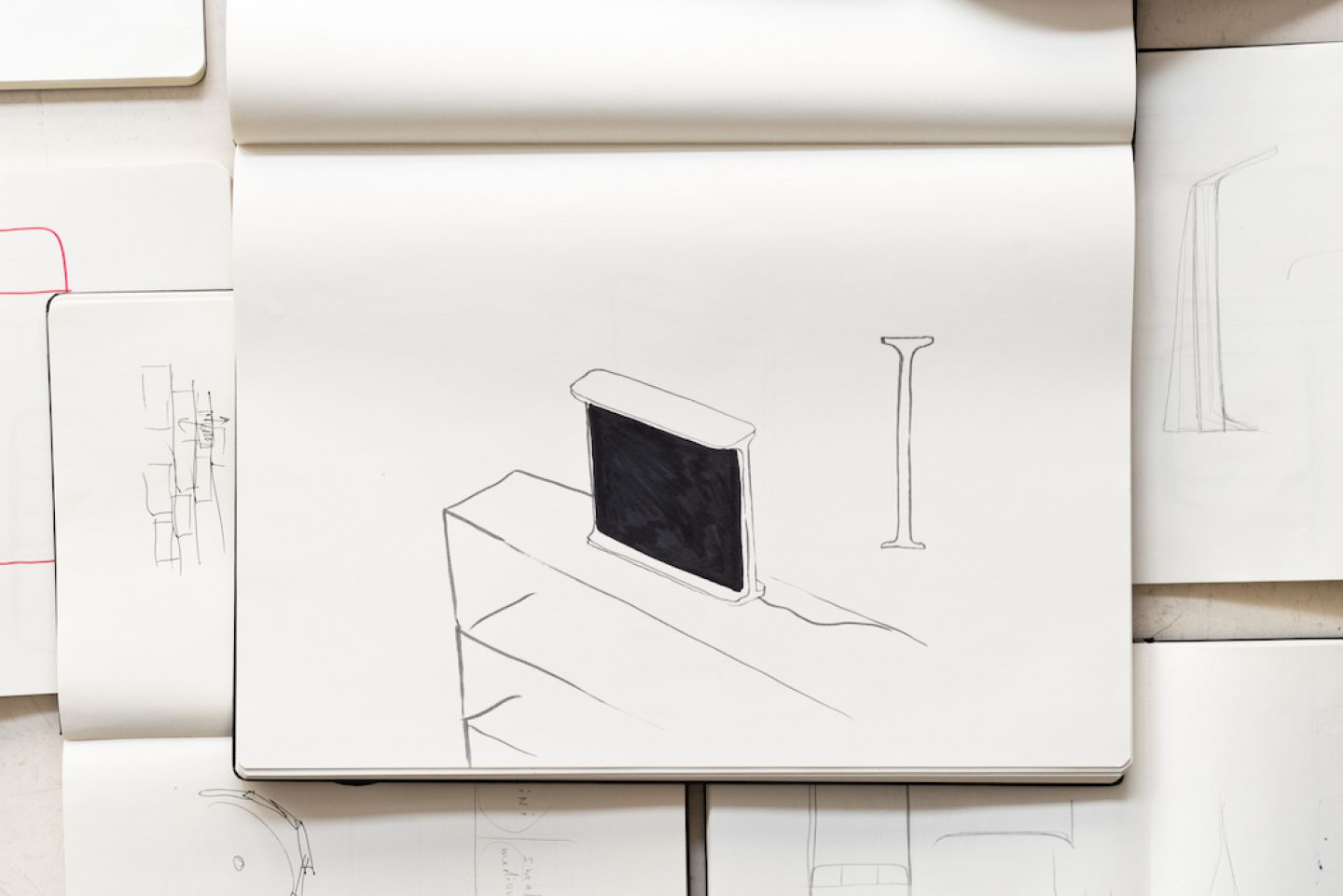

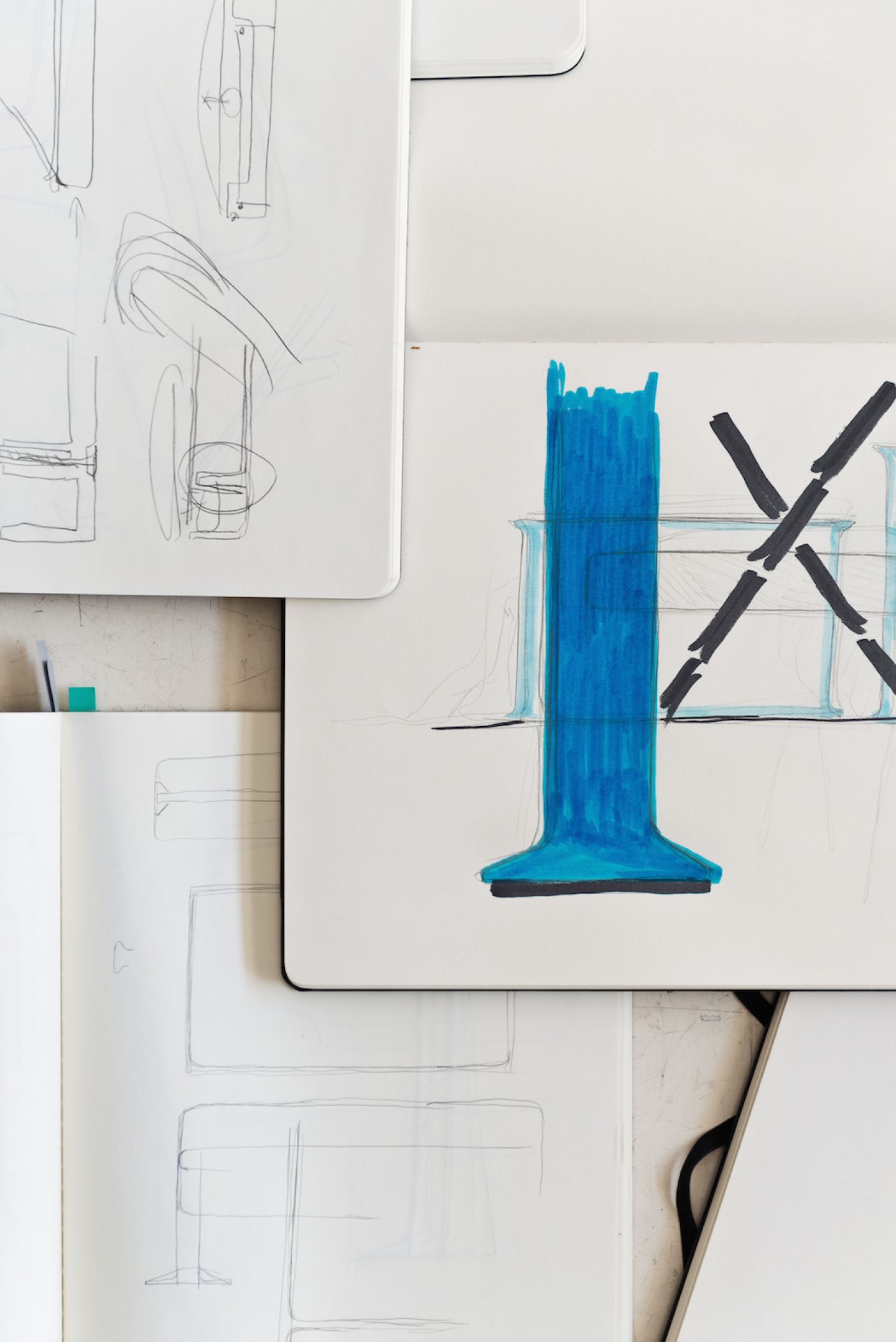

It can go on for quite a long period of time – one month, three months, half a year, and during this time, we might not even start drawing anything, but step by step, we start to define how we will approach a project, guided by intuition. This is the way we start things, and it’s a super fundamental step. In the case of the Samsung Serif, we spent nearly a year and a half discussing how we would work with Samsung, what a TV could be, and how we feel about TV in general. This was a super important part of the job, even though there’s nothing tangible that comes out of this part of the process.

How do you make decisions when you’re not of the same opinion on an issue?

“The big issue with design is the question of culture, of behavior, so you can’t always come back to simple questions like production technique or ergonomics.”We can’t compromise, because product design doesn’t allow for that. We’re dealing with one object, one piece of furniture – it’s so simple. There’s nothing inside it. It’s not like we can put a little bit of Ronan’s idea into it, and a little bit of mine. We have to make a choice. So we find one way or another to make the decision. There are a certain number of rational arguments you can use around design, but quite often they disappear. The big issue with design is the question of culture, of behavior, so you can’t always come back to simple questions like production technique or ergonomics. After a while, all these questions disappear.

I can’t say exactly how we make each decision when we disagree, I just know that at some point one point of view wins out over the other. But of course, we’re not always in disagreement. Often, we kind of naturally go in the same direction. As brothers, we grew up in the same environment so in a certain way, we’ve got the same basic reaction to things like color and proportion. If you would take the two of us, put us in different rooms and ask us the same question regarding a project, we would probably say exactly the same thing.

Throughout the years, you’ve been very successful, which has many positive aspects, but of course it’s not without its downside. How do you deal with media responses to your work, and the pressure resulting from that?

We certainly don’t ignore media attention, especially when it’s related to a product. A product combines many different aspects of life, and so the media reaction to it is fundamental. What is super clear is that the environment in which we live is changing quite a lot, and typologies of objects and furniture are changing quite a lot. Not year to year, but rather decade to decade, and on a broader time scale, the way we were behaving 50 years ago is not the same way we behave now. At the same time, you can see that many of the basic typologies haven’t changed much.

So there are many things that need to be decoded and explained, and many fields to be explored. To advance these things, the media in general is a super powerful tool. Product design takes place in real life – with real companies producing products, and real people behind them. So there are a lot of limitations. You can’t afford too much risk. Exhibitions are a really important way for us to explore new directions, and books, pictures, and the media are all super interesting ways to develop certain aspects of object design. So in fact, the media is a super positive tool for us.

You’ve had an extremely high output in recent years. What do you do between projects to clear your head again?

[Laughs] I don’t really know. We really do spend a lot of time in the studio. It takes up most of our lives. I don’t really make a distinction between the pleasure of being in the studio and the burden of being there. Our grandparents were all farmers – quite traditional people from the west of France, and the only thing that was important for them was work, all the time. So I go back to the studio over and over again, and sometimes I feel I should move away from it, but actually I can’t.

We’re quite obsessed by things, and we want to succeed at the things we obsess about. So ultimately, yes – we’ve been doing many things but even so, what we do is only a small part of the world we live in. There are so many things to do, so we keep going back to the studio. You know [Italian architect] Andrea Branzi, from Italy? We know him quite well and had an exhibition with him quite a long time ago, in Cologne. I met him again quite recently – three or four years ago – and he told me, “You need to go on holiday – it’s super important for the job you do, to keep some distance from it.” But I never really managed to grasp the meaning of this proposal.

"There are so many things to do, so we keep going back to the studio."

Your work spans various design disciplines, from creating home accessories and jewellery to architecture. What was it like to design a TV in general – and more specifically when the dominant screens in our lives are our laptops and smartphones?

“We felt like we needed to find different attributes, so that the TV would be less of a monument and more something that in a way is more humble.”Because we don’t own a TV ourselves, we spent a lot of time questioning the need for a TV, and on the other hand, we were facing the fact that a TV is something super normal. Most people own one. We were discussing why the TVs around us are not exactly what we would like to own, and why the language and behaviors around TVs are not exactly what we feel is right. So we spent a lot of time discussing these things, and step by step, the conclusion we came to is that most TVs are monuments to themselves. Monuments to their own size. And a TV is slightly like a car, you know – it used to be this very symbolic thing that describes your income, the way you’re progressing in life. And at the end, we felt like we needed to find different attributes, so that the TV would be less of a monument and more something that in a way is more humble at the end, more subtle, and takes place in the context of everyday life. Let’s say it was a conceptual statement.

What process did you follow in creating the Serif?

The way we did it was we asked Samsung to send us a lot of TVs that we opened and destroyed, and then rebuilt again. I think it was a very easy and natural process, where we were not at all fascinated by the technology itself – but step by step it aligned really naturally with our usual product design methods – the way that we assemble prototypes, and the way we explore things by making them. We were not really thinking about future technologies. We were just trying to do something right now with what we had in our hands, and in our studio.

The Serif’s design includes the interface and a remote control. What were some of the main considerations and challenges in creating the complementary elements?

We are obsessed with product design. So in the end, it’s not complicated. We wanted to design everything. At one point, we started to take care of everything, to show Samsung we were taking care of everything. As I mentioned earlier, one quality that Ronan and I share is that we are super independent, and we have quite a particular practice, most of the time our products settle quite well into the company we’re working with. I don’t know how, but we manage to convince people that we want to do well for them. So we quite quickly built up a mutual sense of trust and confidence in each other. So they just let us do our thing. I’m quite fascinated with people who design typography. Because they create something which is super fine, super delicate, really subtle and at the same time slightly invisible, not at all dogmatic. Nobody knows exactly what it is they are doing. Regarding the entire Serif project, we started to take care of everything. We had the idea that it had to be subtle and humble enough not to be this piece of technology claiming to be super strong and efficient. That’s not what we wanted.

What was the inspiration behind the ‘I’-shaped design?

“The ‘I’ shape in itself was never intended at the beginning.”What we wanted – or what we tried to do – was to make one object without too many details – concise enough, condensed enough. And for this, while we were working on the edge of the screen, we discovered that if we brought the bottom of the screen to the edge, it would naturally create the base of the screen, so we could avoid having to create a separate stand. Step by step, the Serif became more of a frame, in a way – a frame surrounding a picture. In this way, the design connects to an idea with a history older than the TV itself: the idea of framing a picture. And yes, the ‘I’ shape in itself was never intended at the beginning. We didn’t plan that the TV would look like the letter ‘I’ – that simply came as a consequence of all the design decisions we made during the process, and that’s why we called the TV ‘Serif’ at the end. It was a way to find a name that subtly described the shape. It’s a name root in a certain simplicity, not the kind of name we could have invented out of nowhere. Sometimes people say, “Oh, this TV was imagined from the letter ‘I’. But no, it actually came the other way around.

You’ve designed chairs, tables, vases, lamps and now also a TV. Is there anything that you’ve always wanted to create?

Well, I think the world that surrounds us is not super well designed in general. So Ronan and I feel like there is so much to do all around us. In principle, many subject would interest us, and the more popular they are, the more thrilling it would be to develop them. For example, I would be happy to design a car, a train, or some transportation…the only thing that we are always making sure of is that we are not putting any pressure on our studio. Our studio is super small – we are eight in total – and we want to keep it a certain size so that we can handle everything on our own, to keep things streamlined and at the scale we want.

So yes, now that you ask me, I would love to do a car, because I’m not a car lover. I would probably have a different point of view than most professional car designers. It became really clear during the development of Serif that everybody wanted to take advantage of the fact that we were totally new to the question of a TV. Because when you start something, of course you make many mistakes, but you bring a different vision to someone who knows a lot about it.

"When you start something, of course you make many mistakes, but you bring a different vision to someone who knows a lot about it."

All images © courtesy of Samsung

– In collaboration with Samsung –