The Melancholic Lyricism Of Robert Montgomery

- Name

- Robert Montgomery

- Images

- Anna Dorothea Ker

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

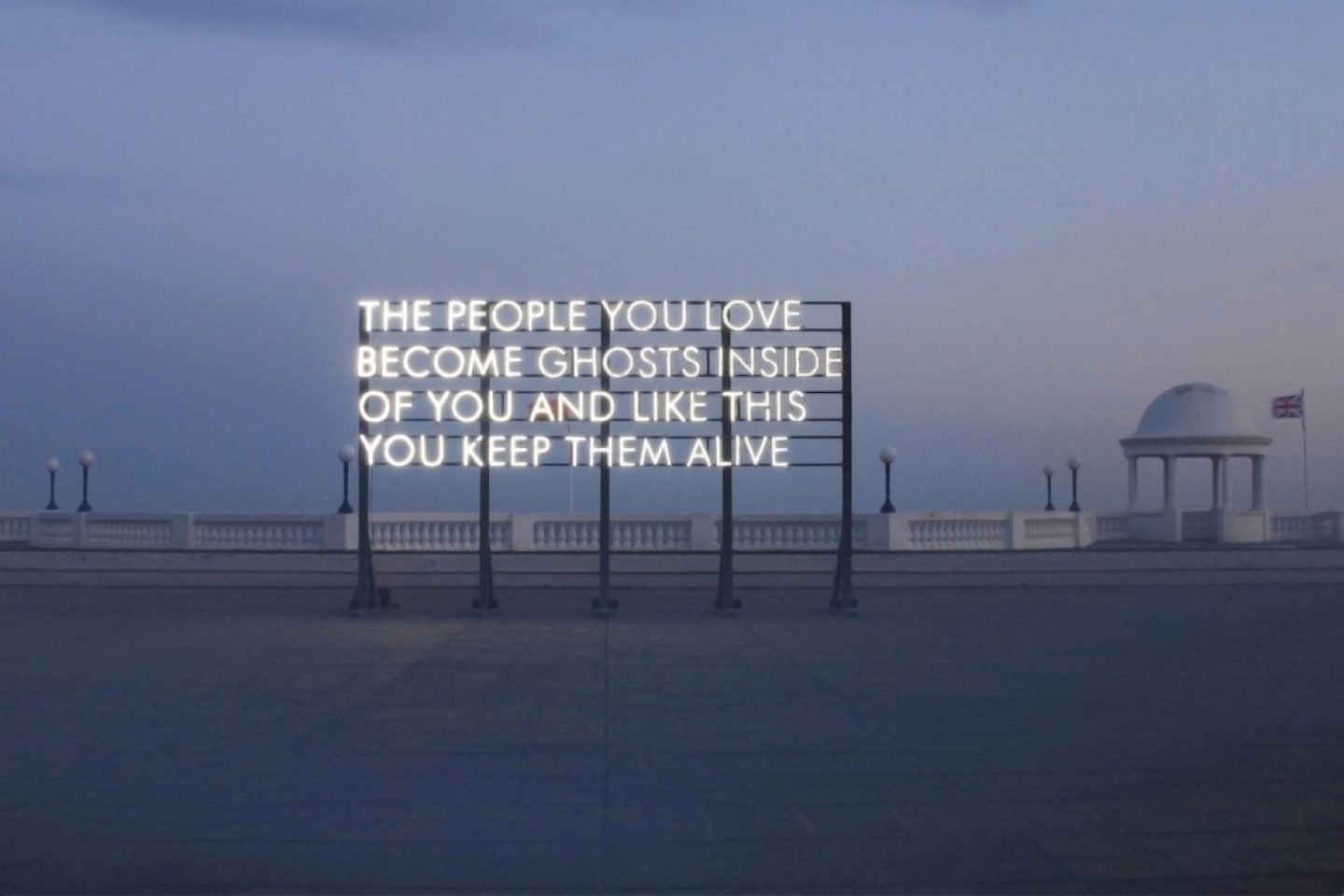

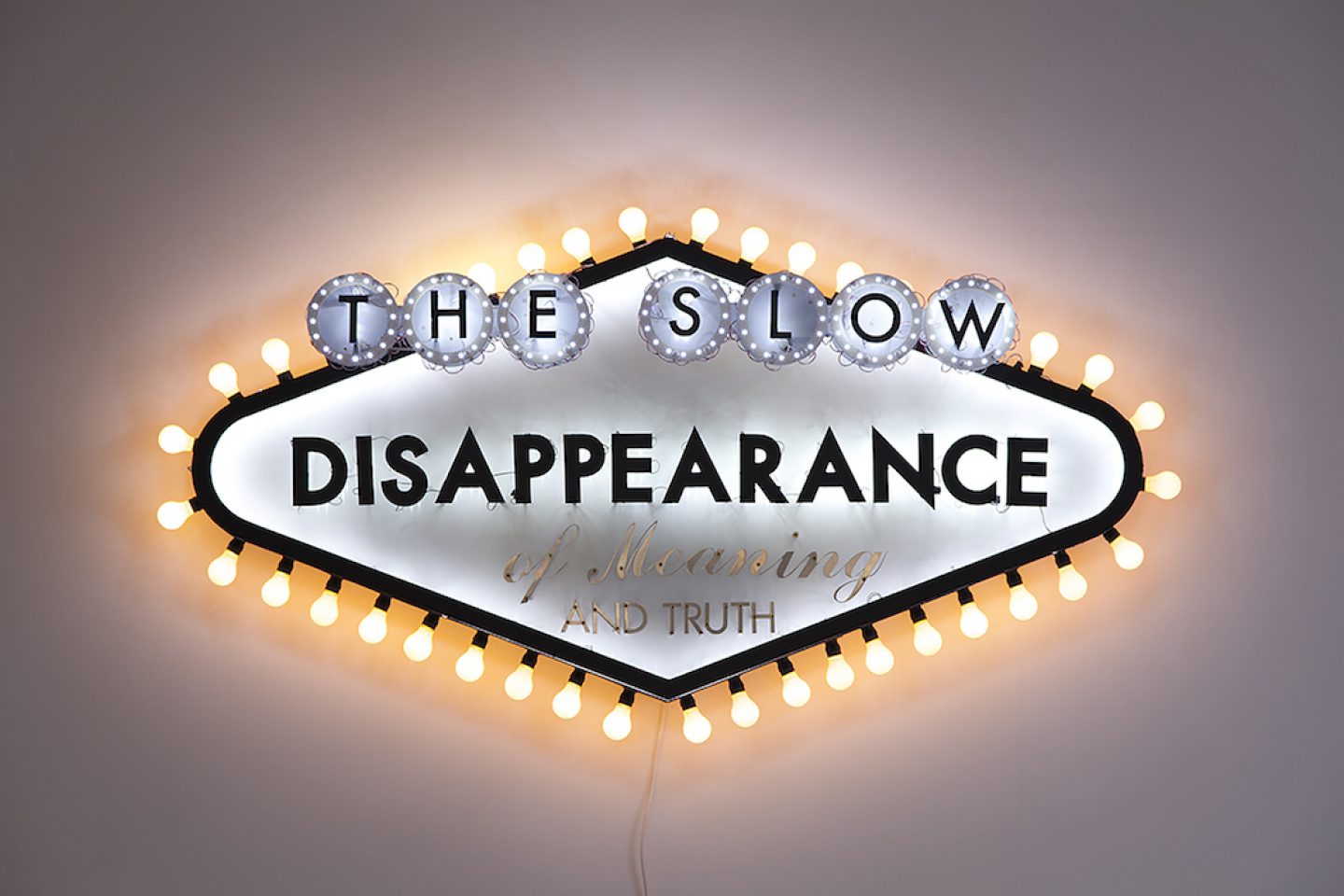

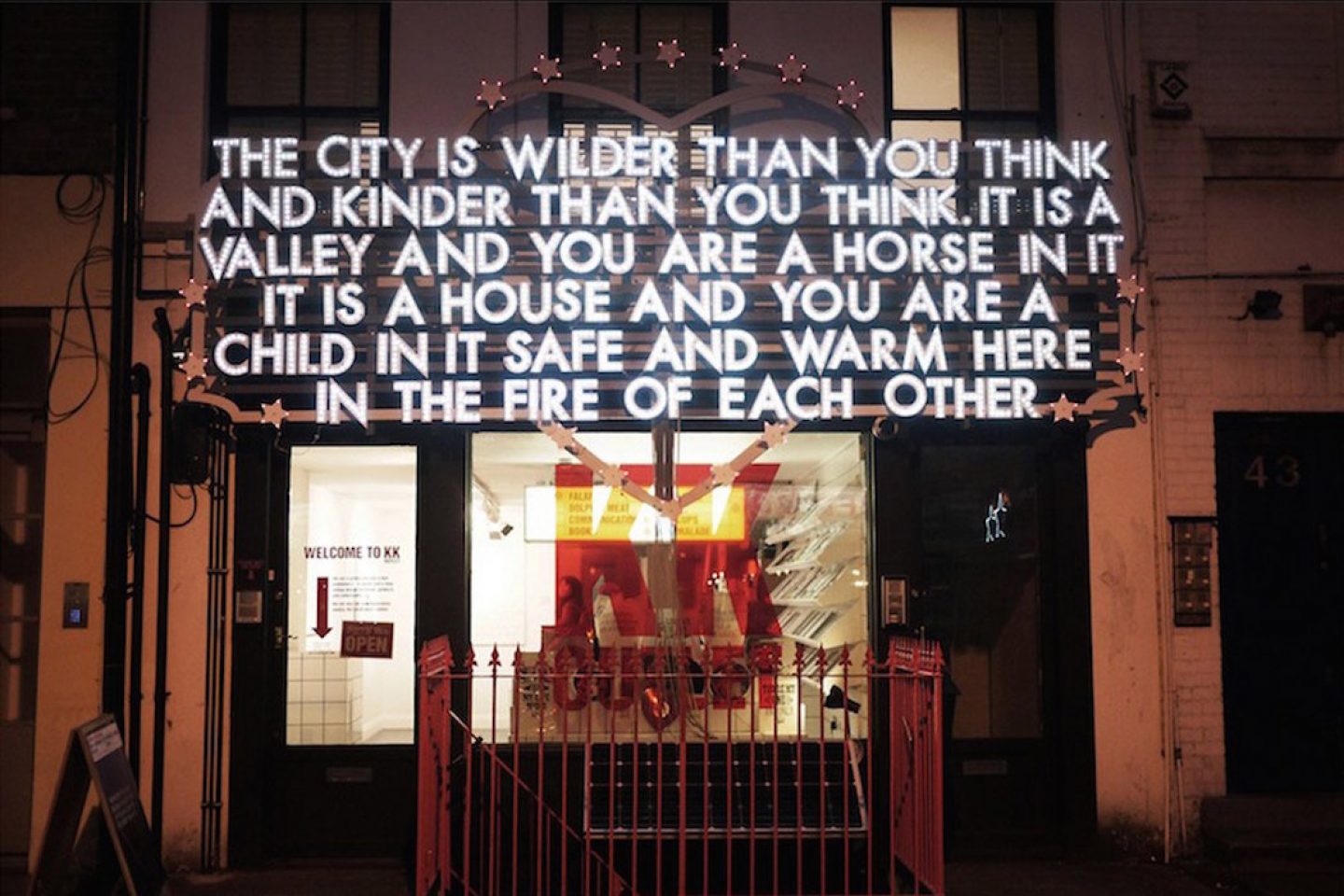

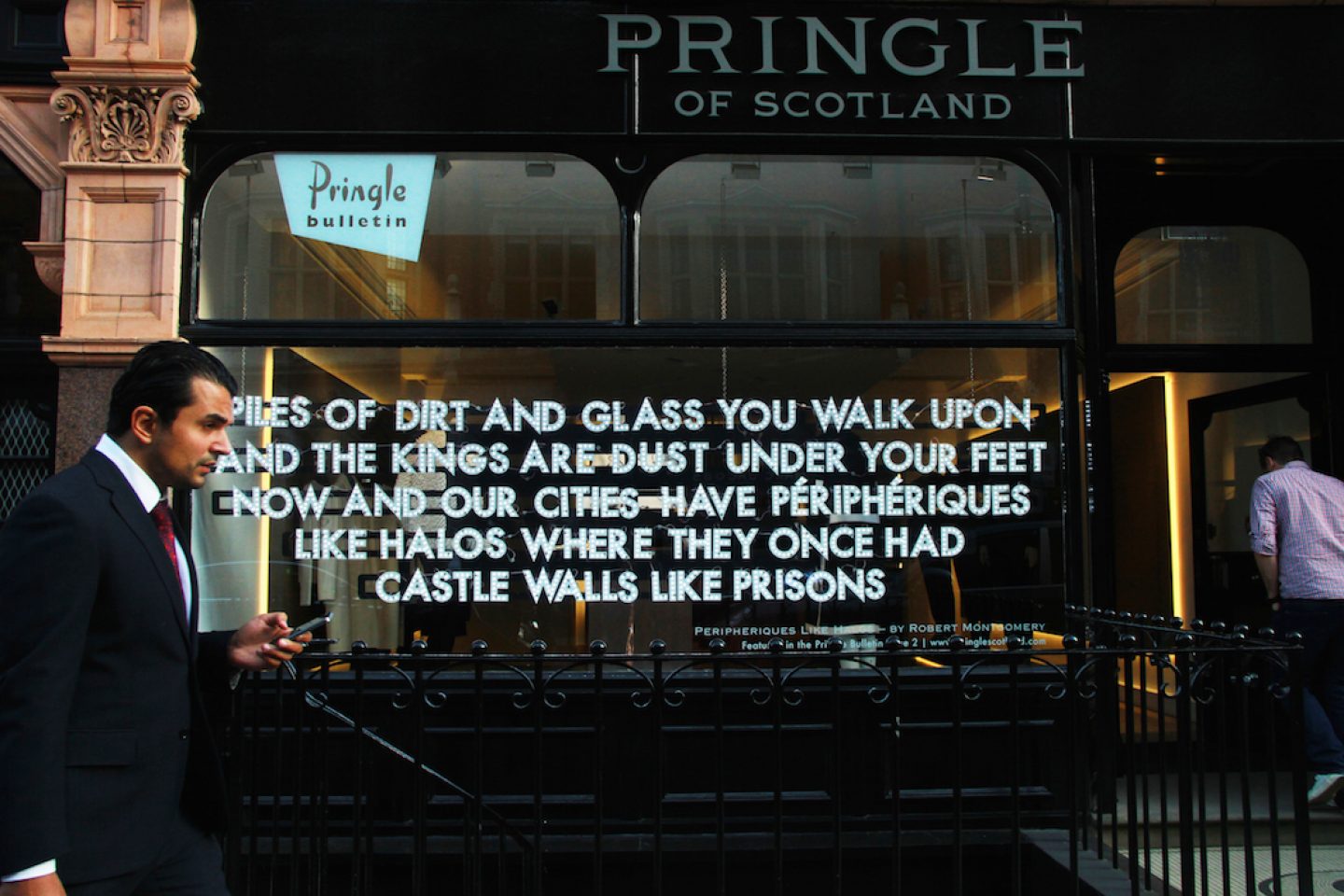

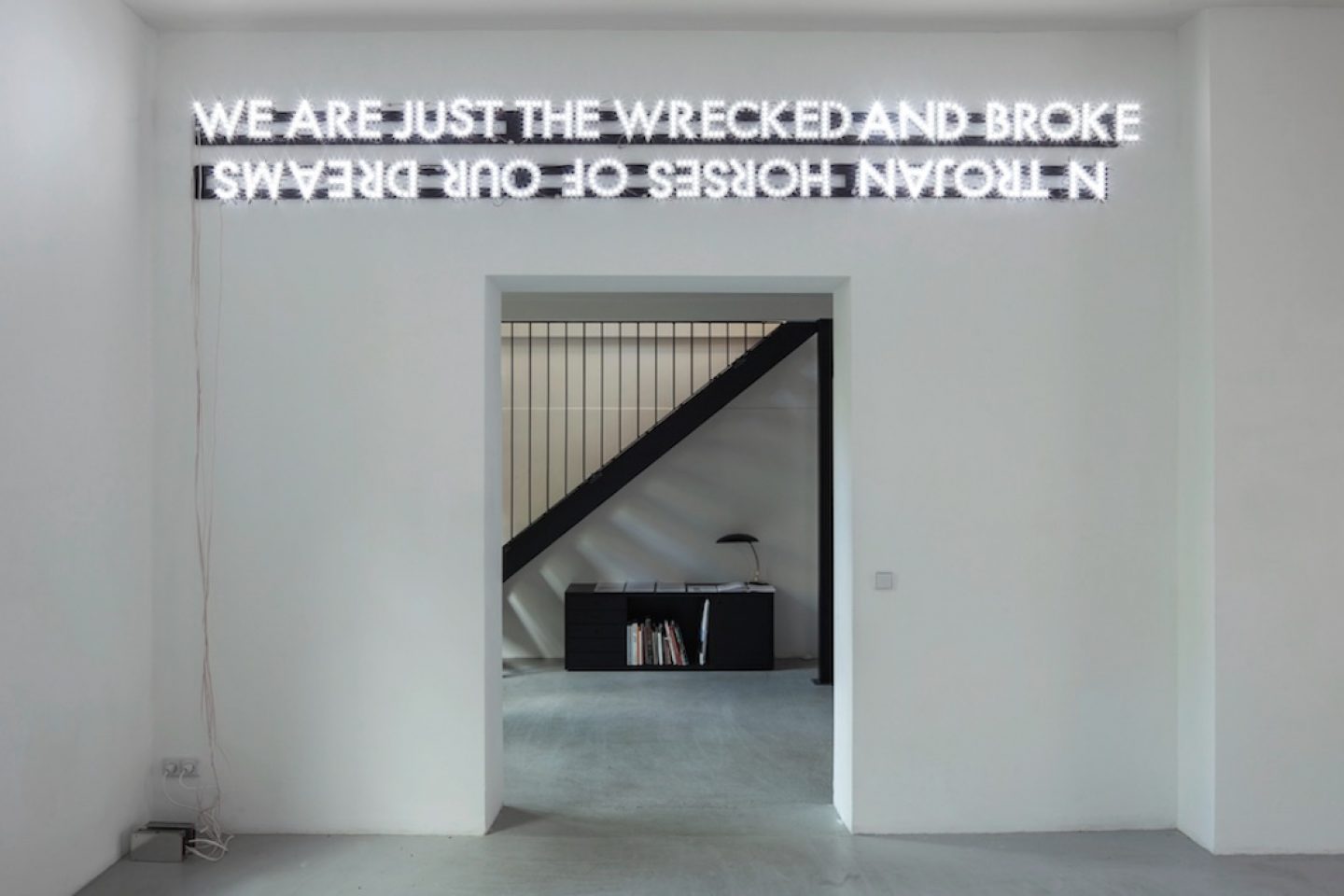

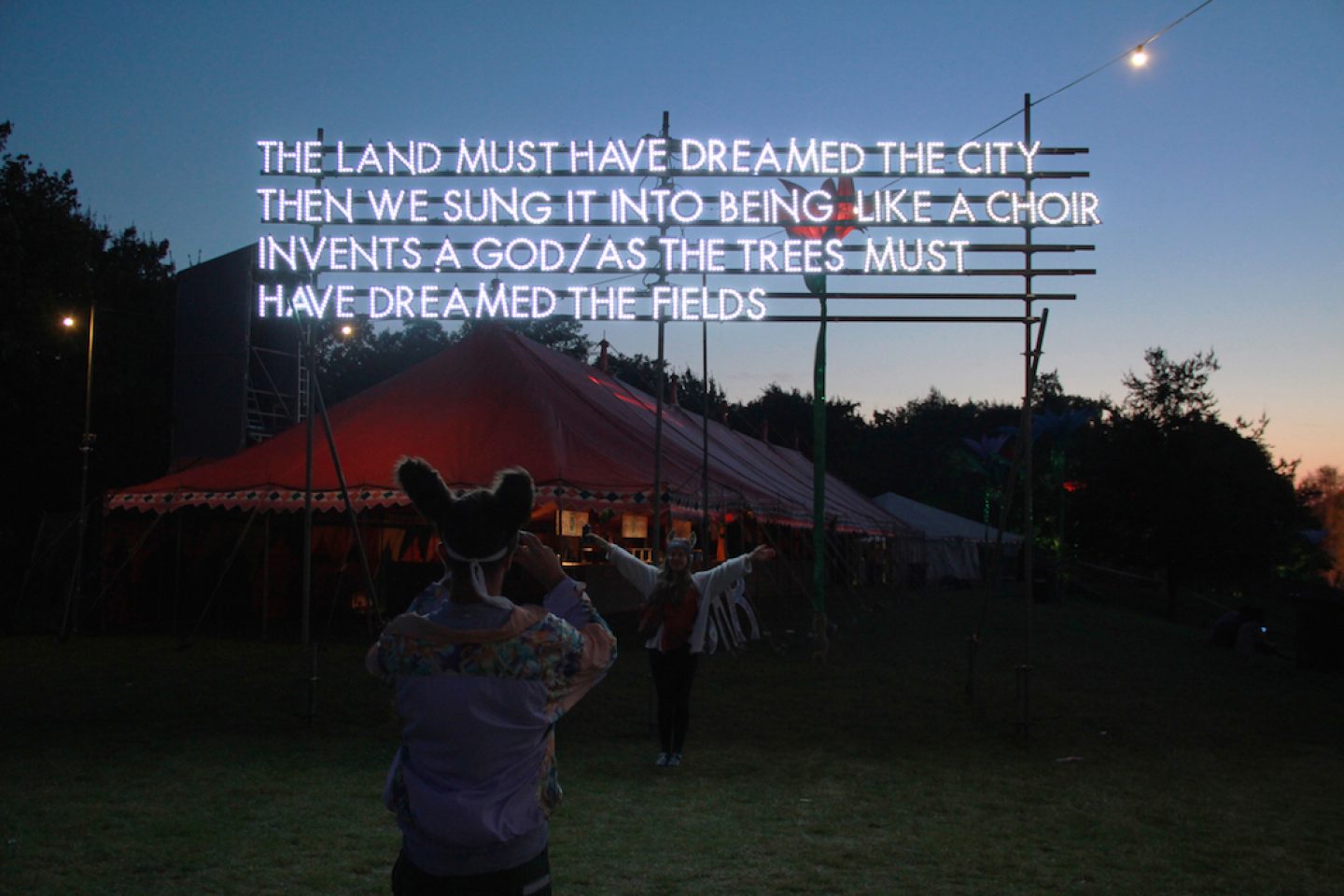

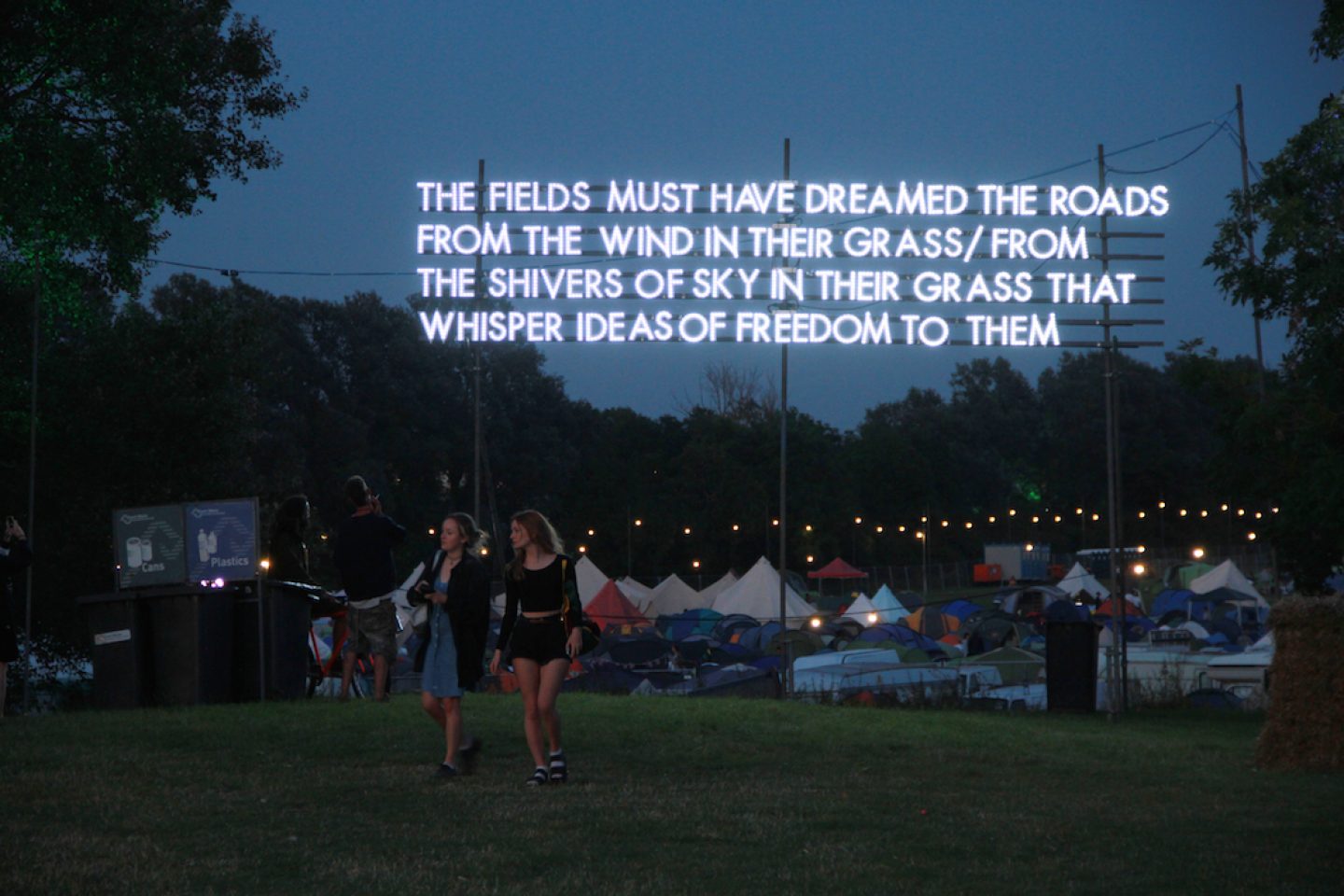

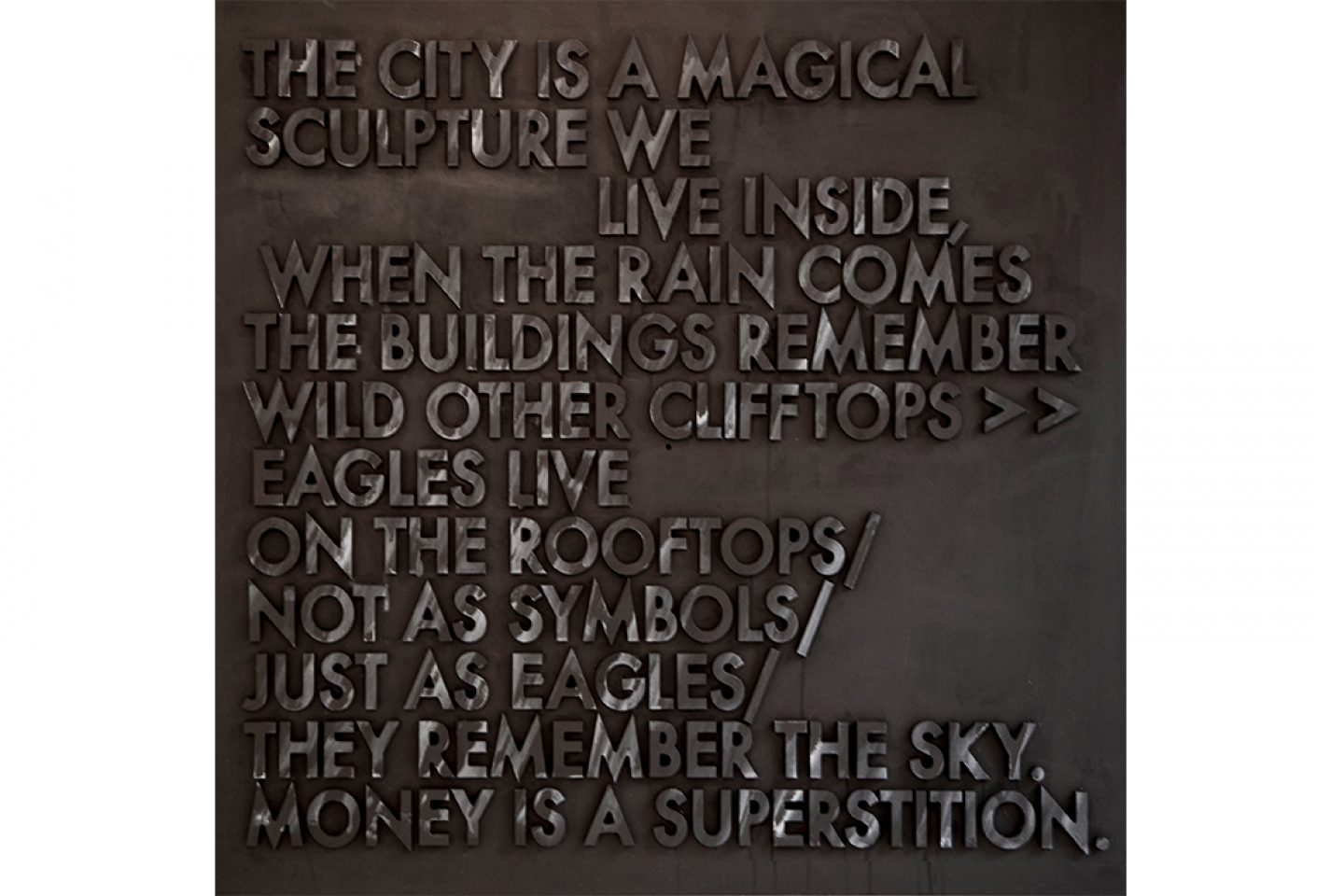

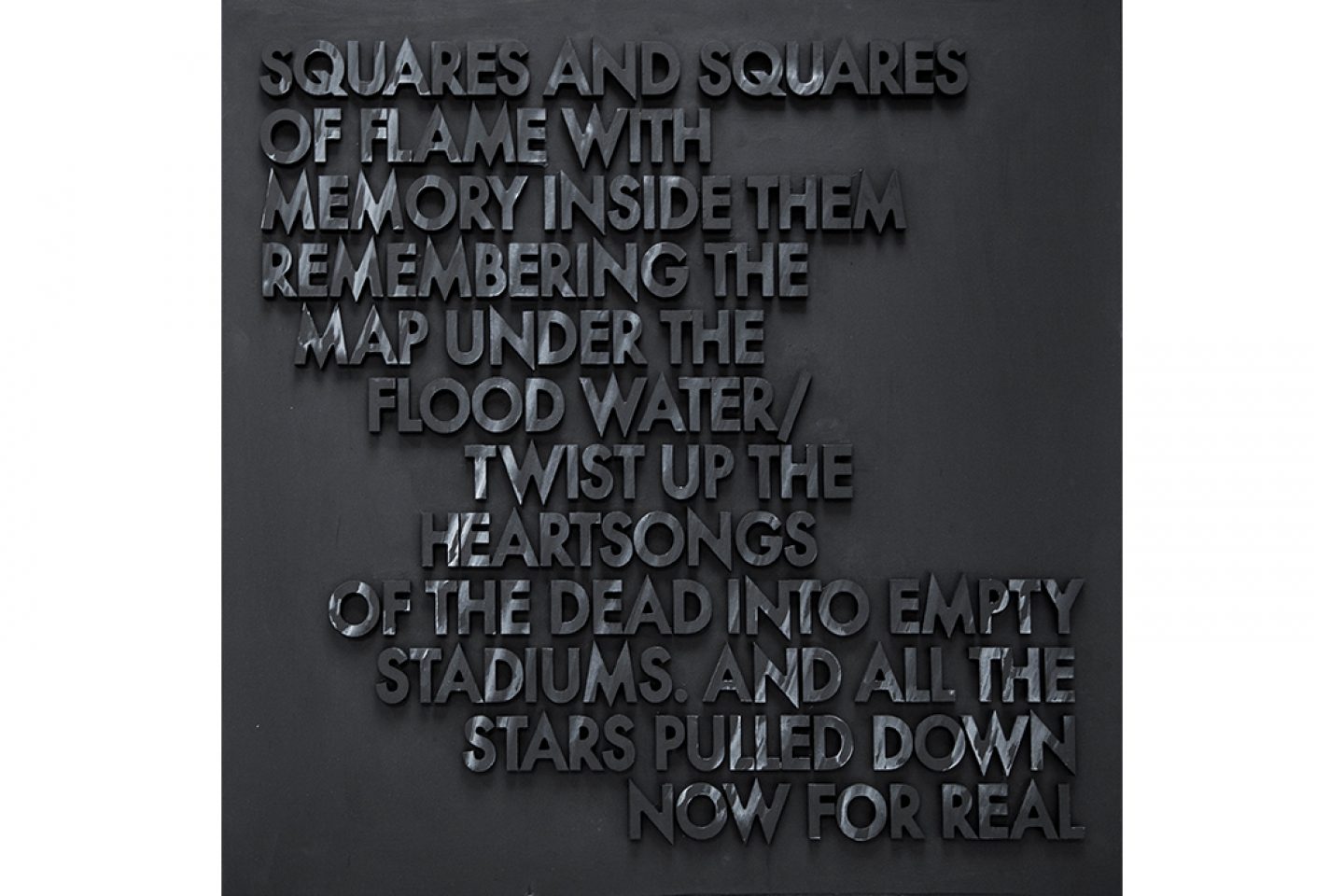

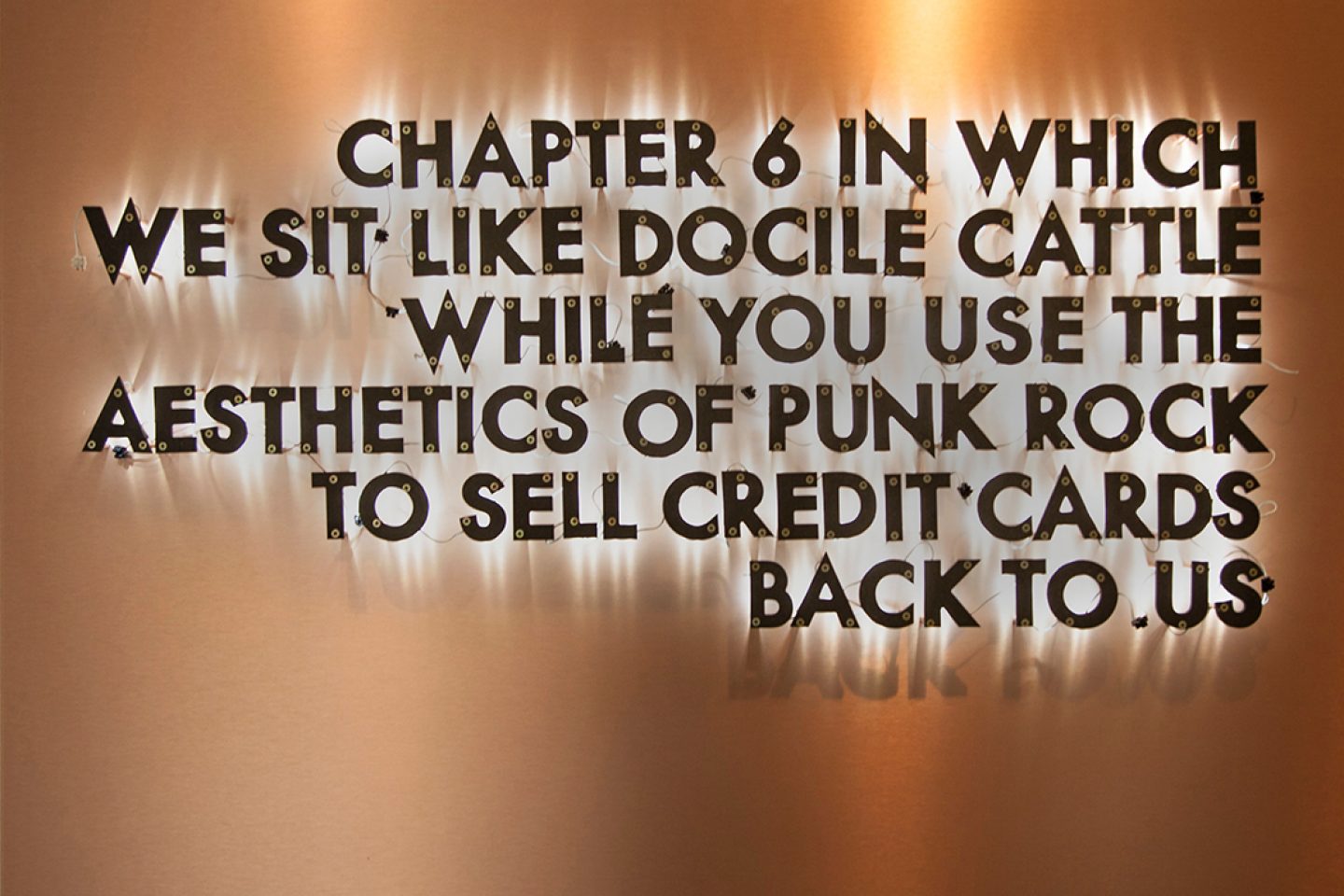

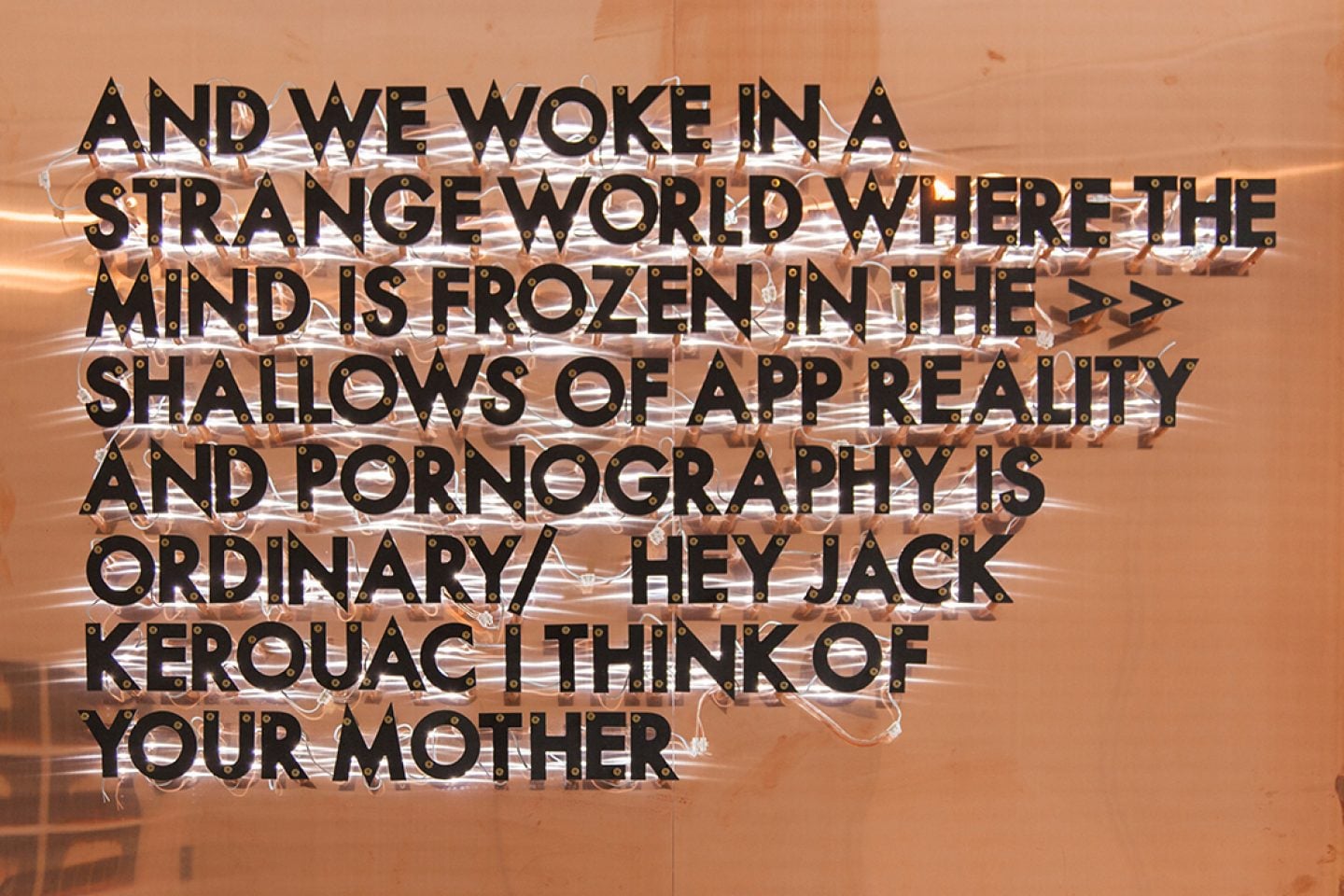

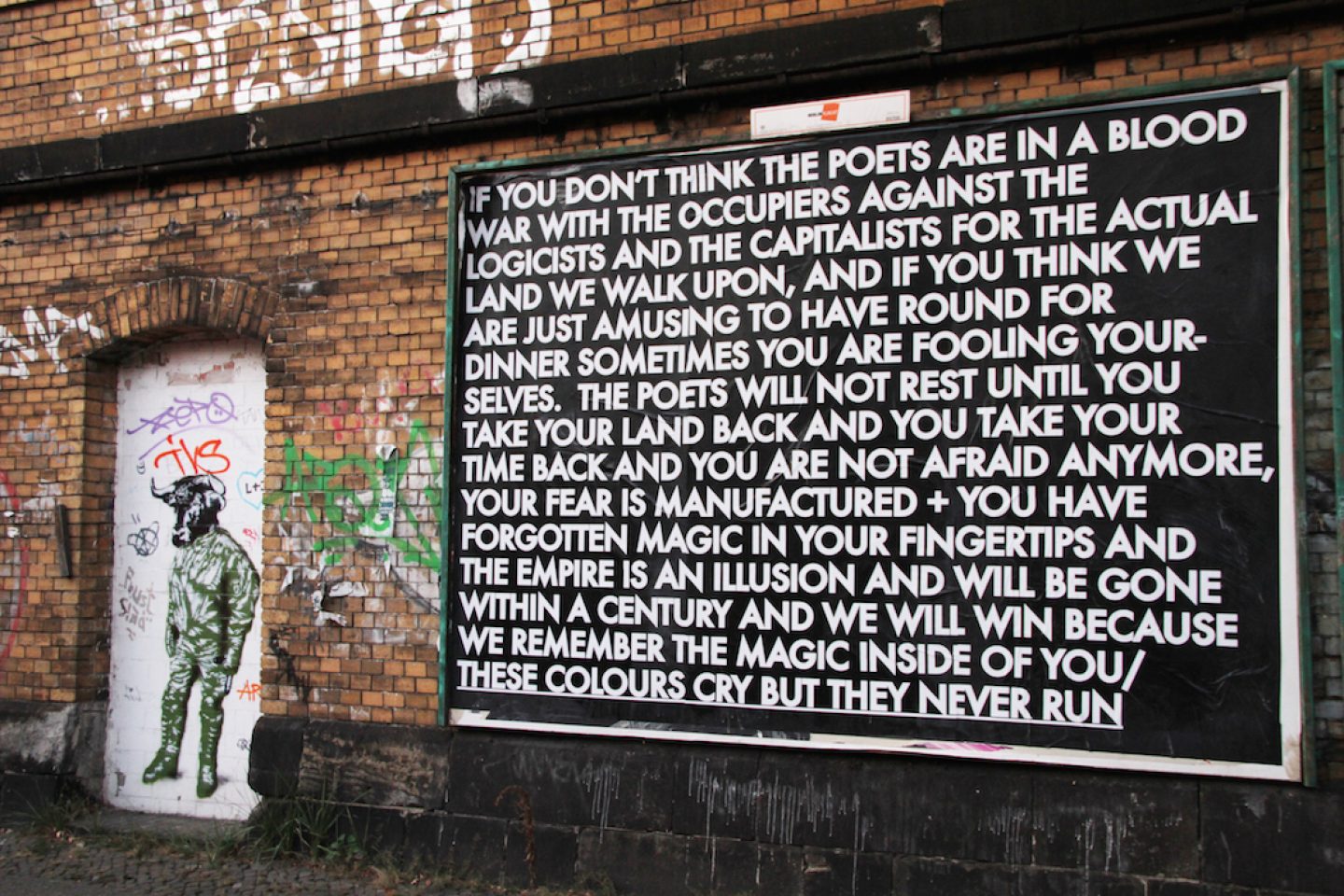

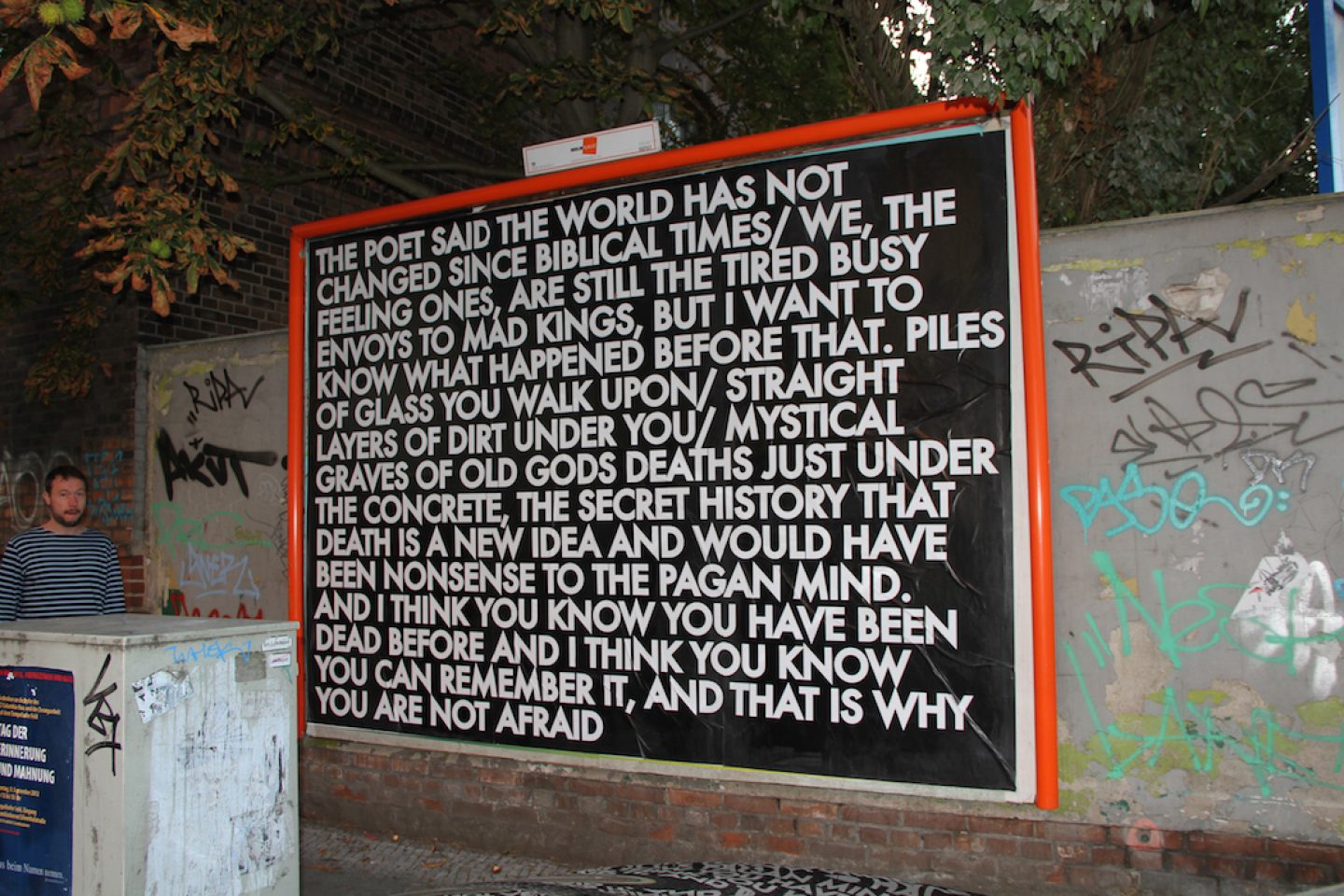

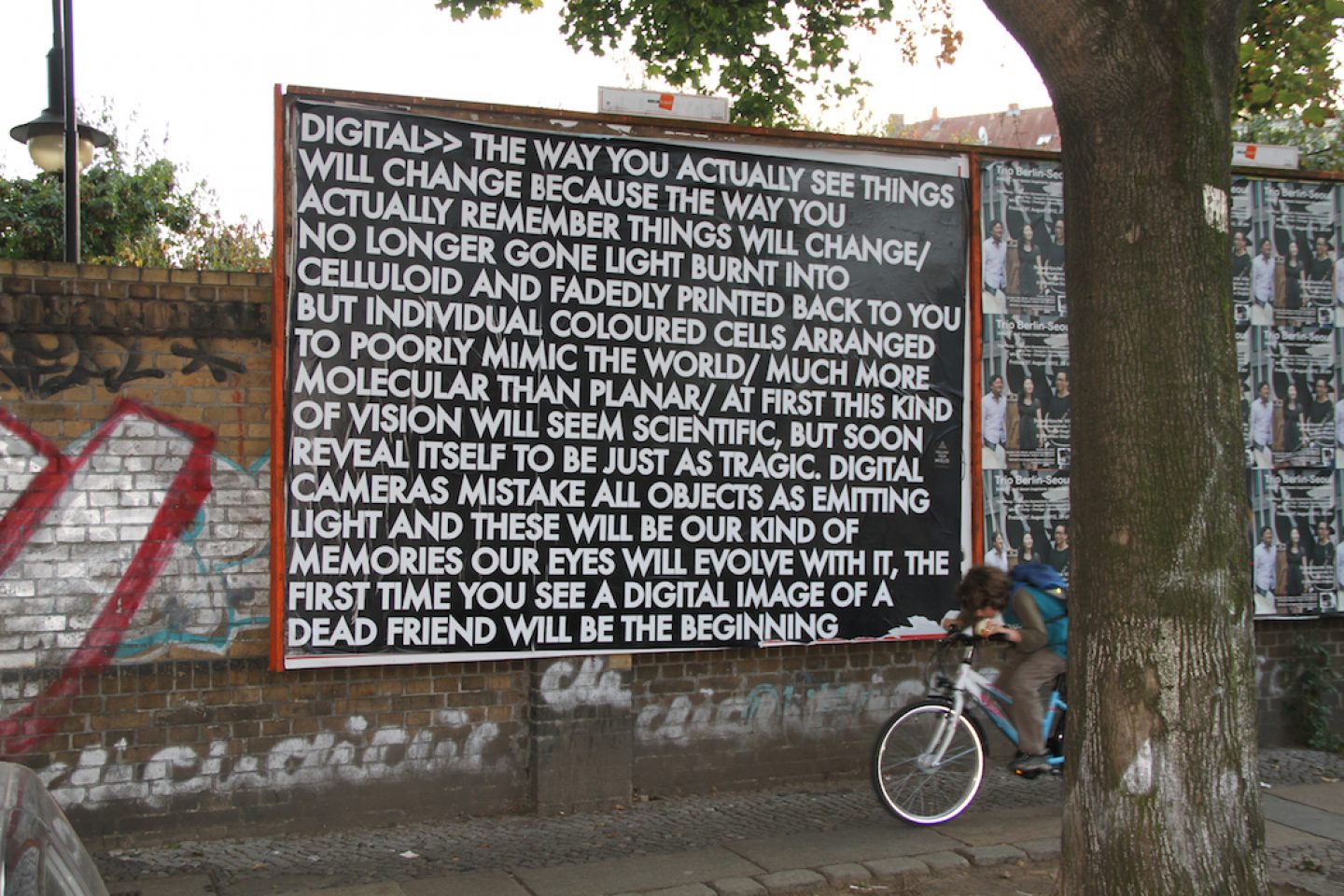

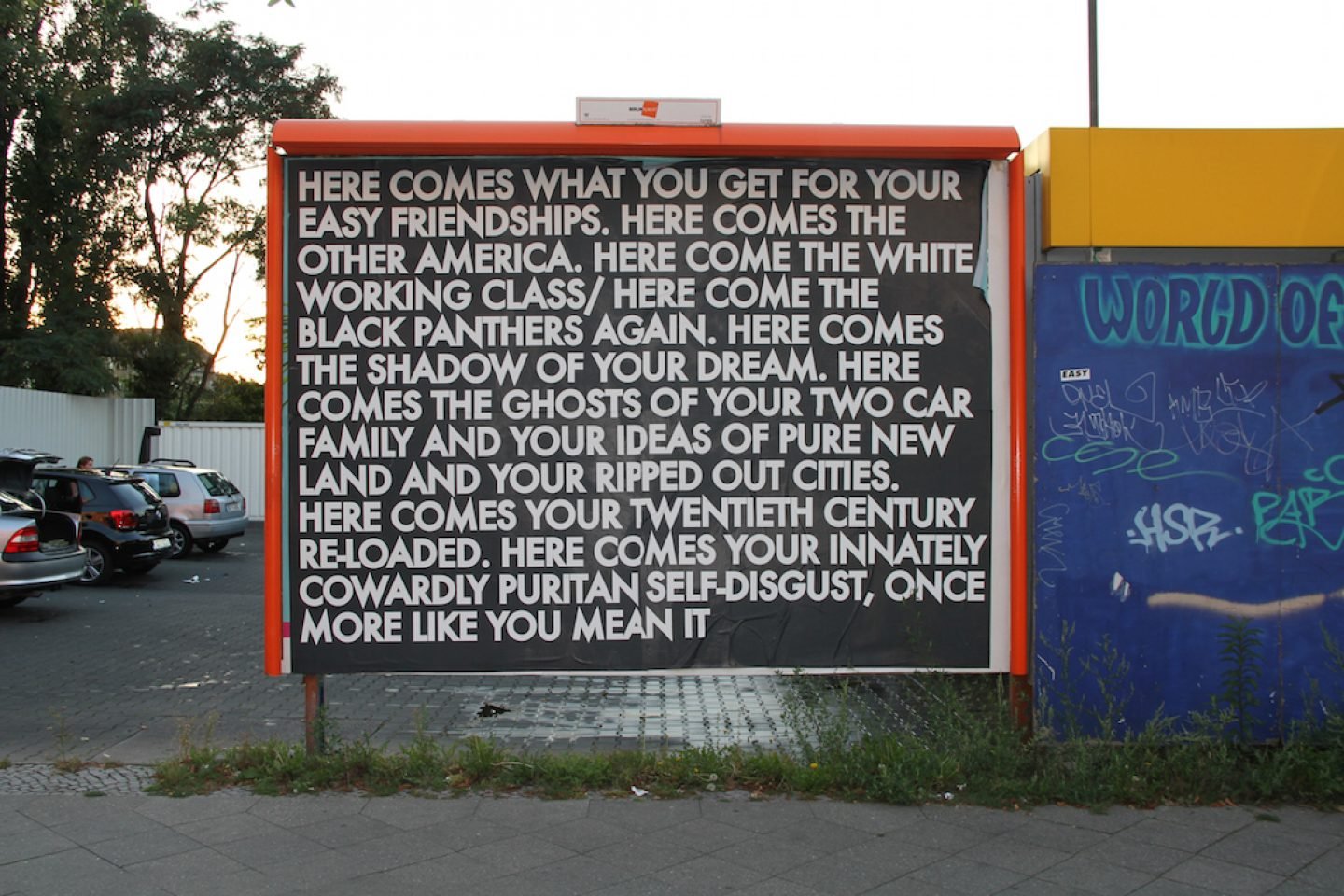

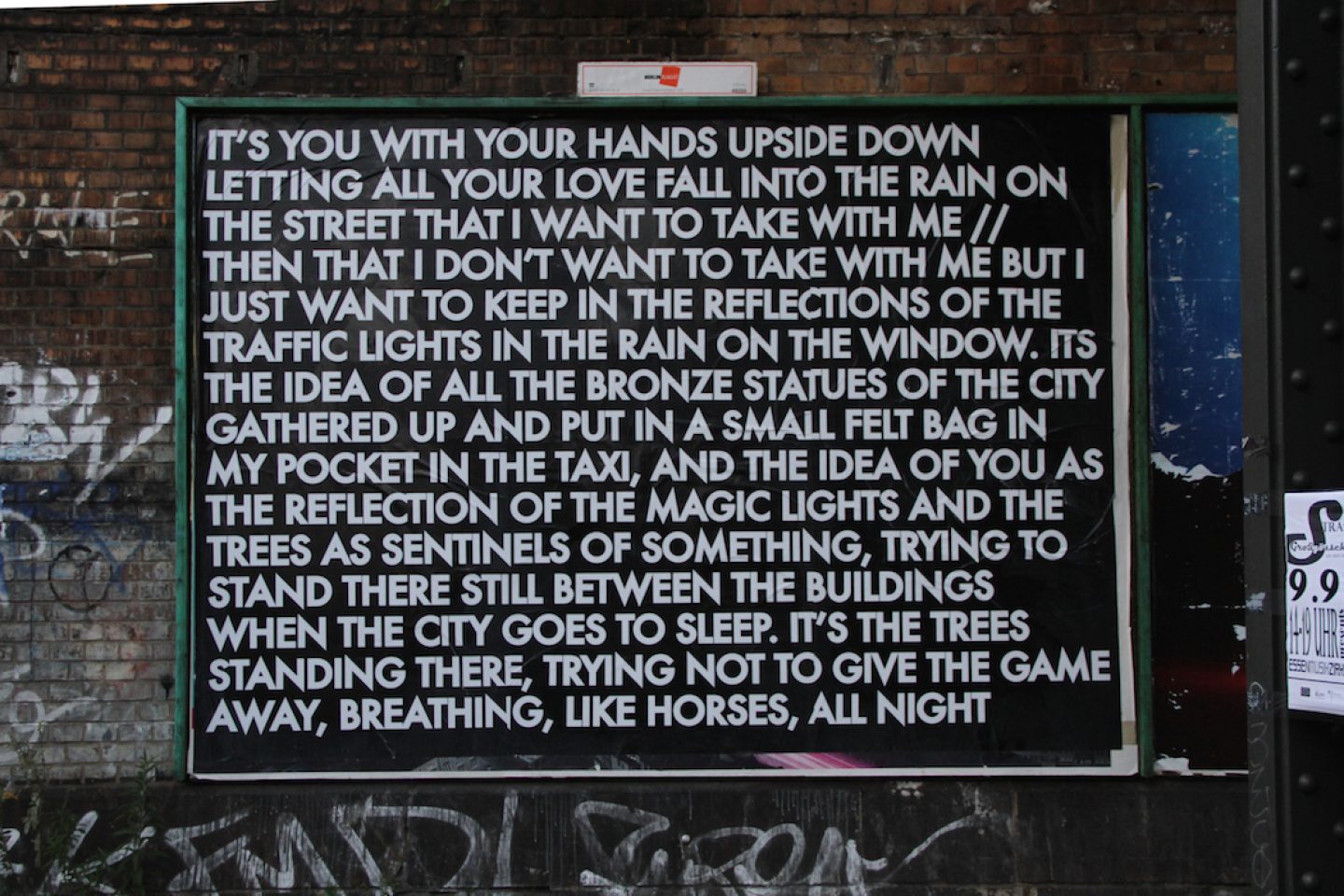

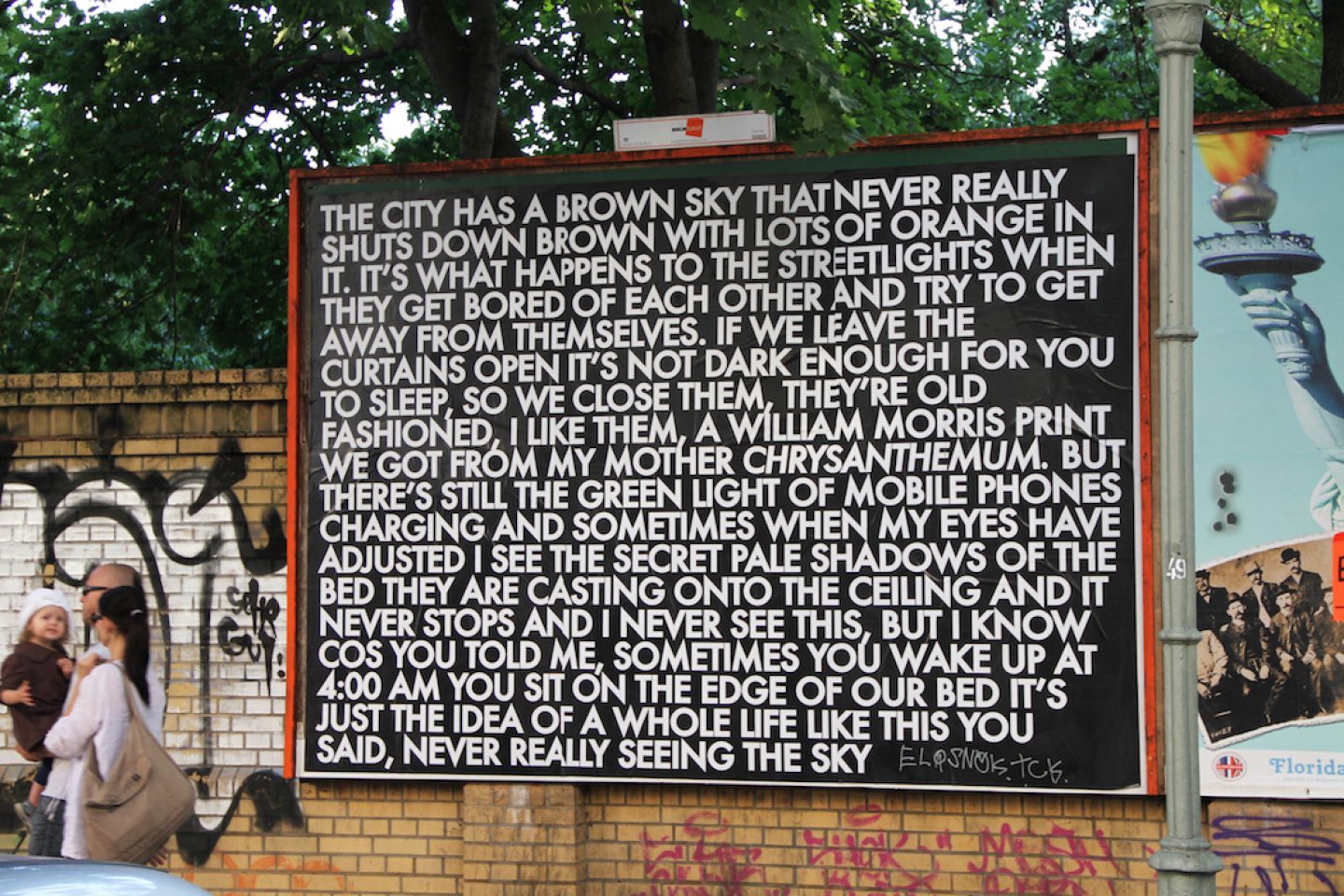

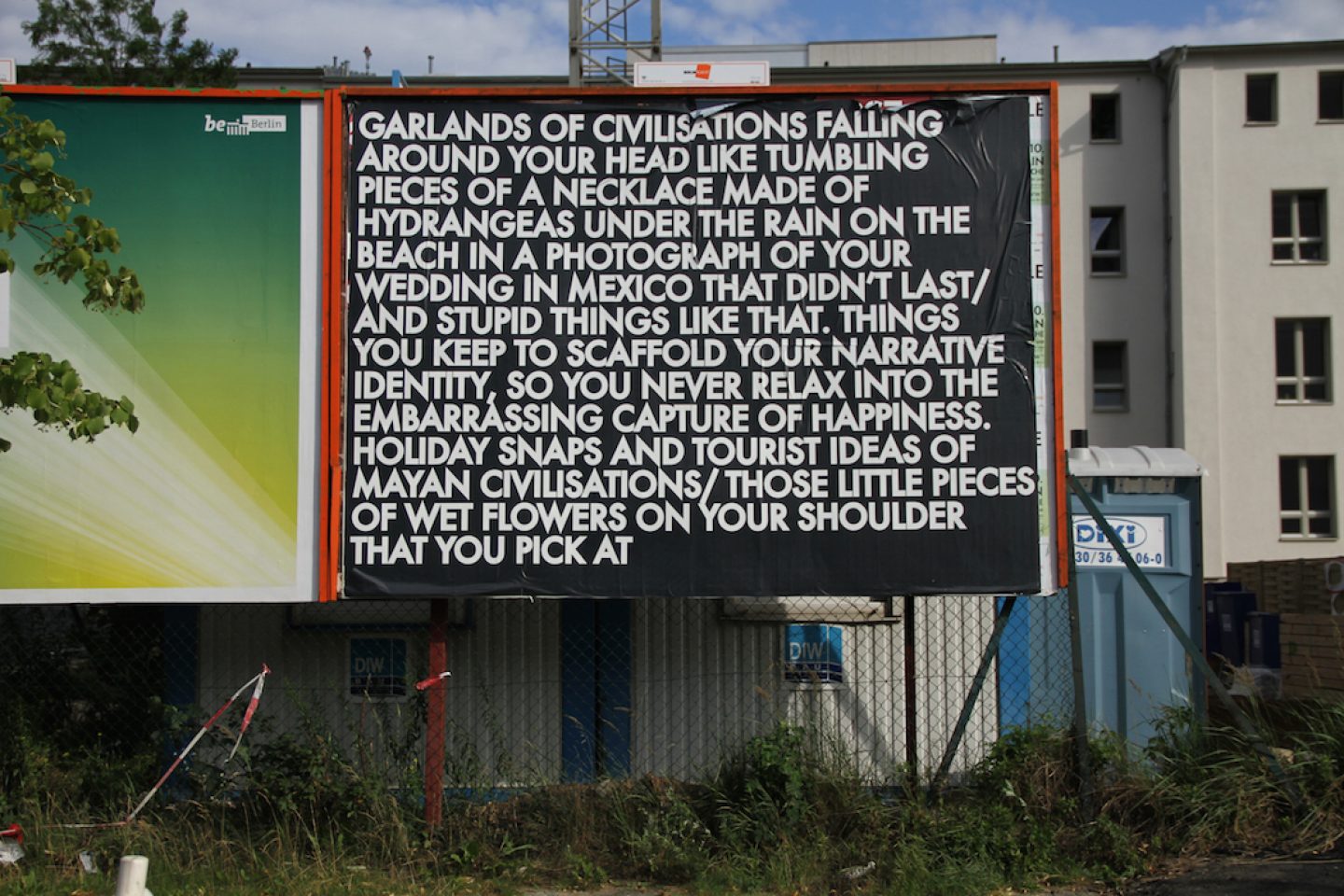

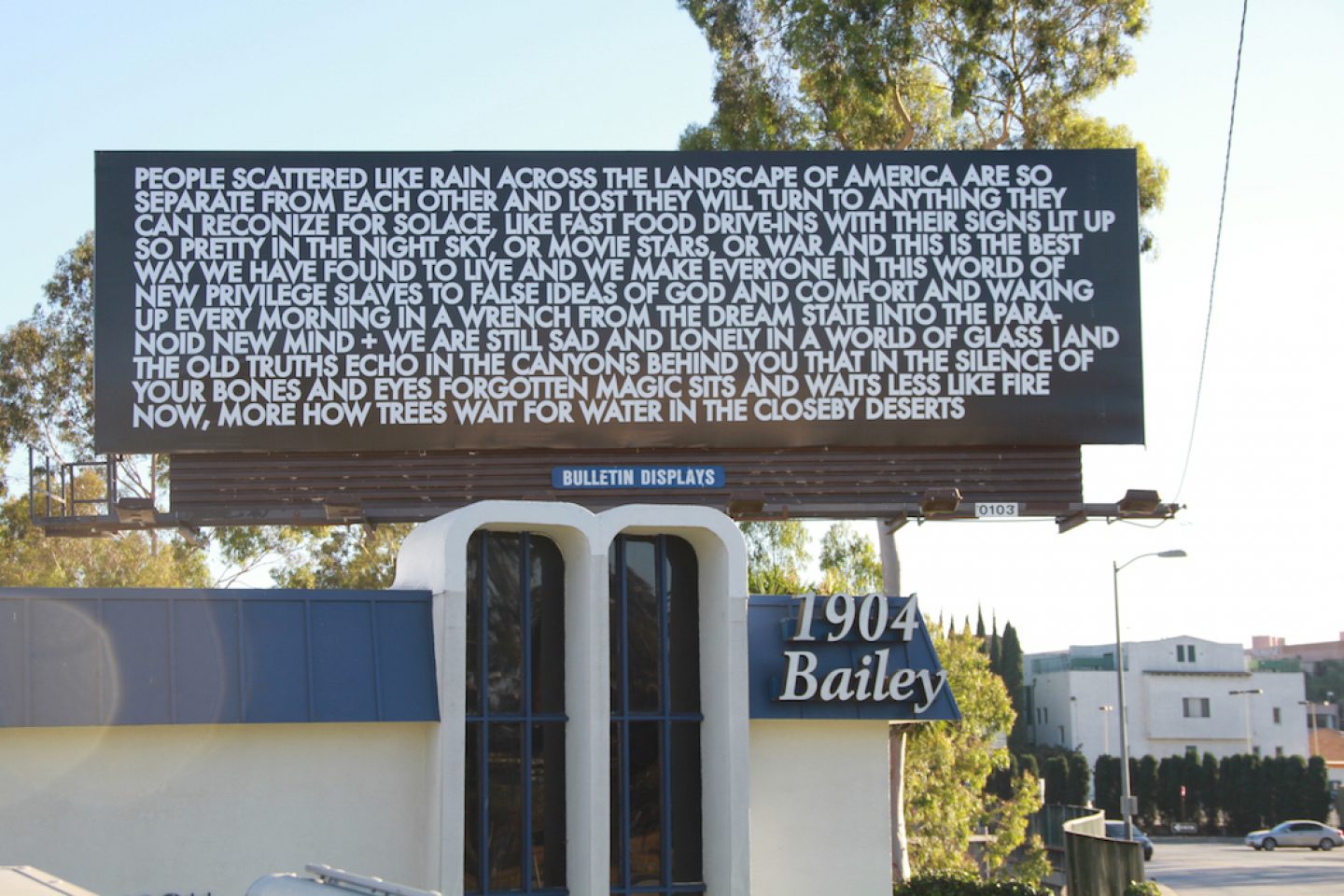

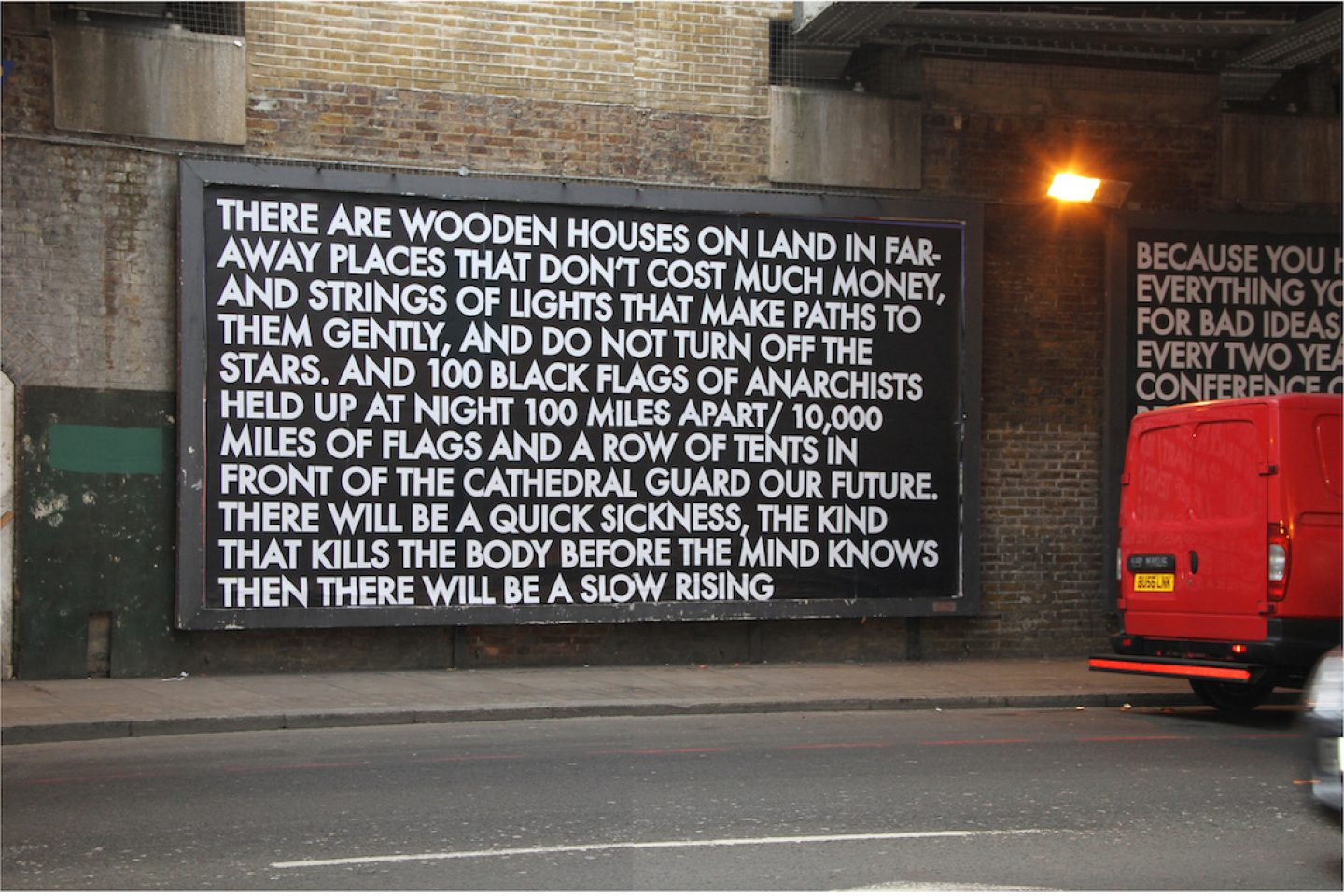

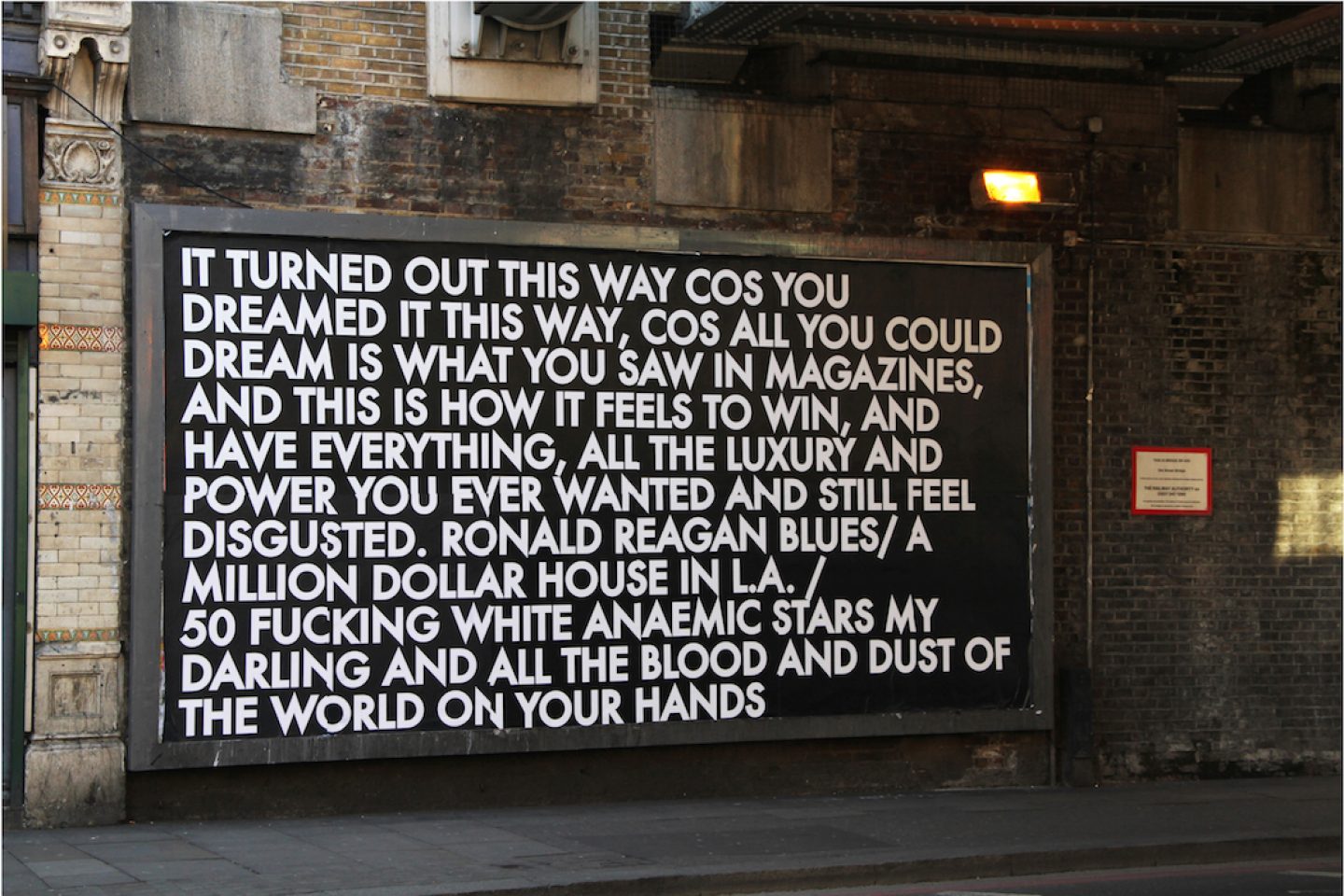

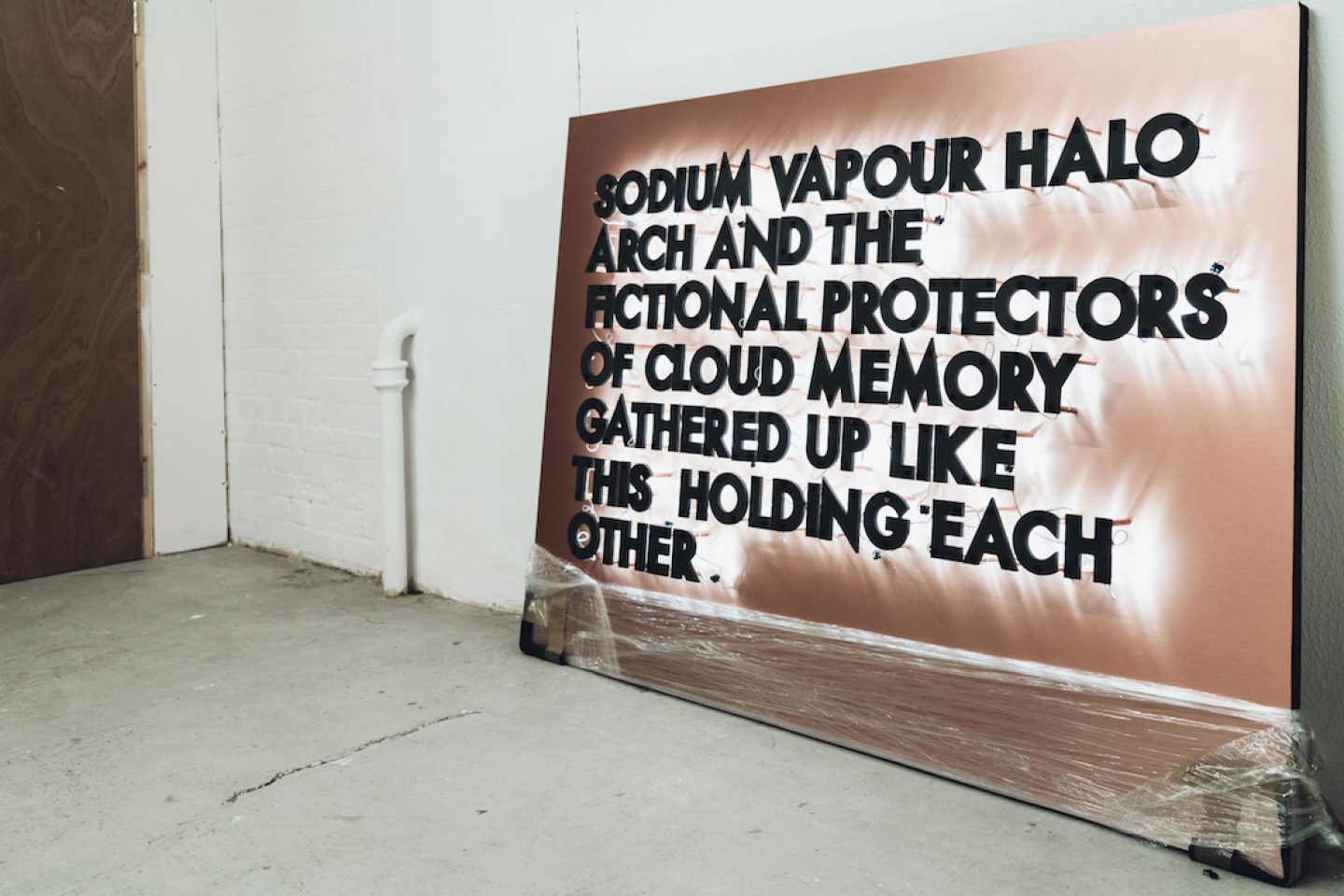

Over the past decade, the words of Robert Montgomery have been lighting up skies and breaking hearts the world over. Working in a conceptual, post-Situationist tradition, the Scottish-born artist has lent his voice to urban spaces from Izmir to Kerala, supplying verse after verse of poetry that, while gently-spun, cuts to the core of the most crucial issues of our time.

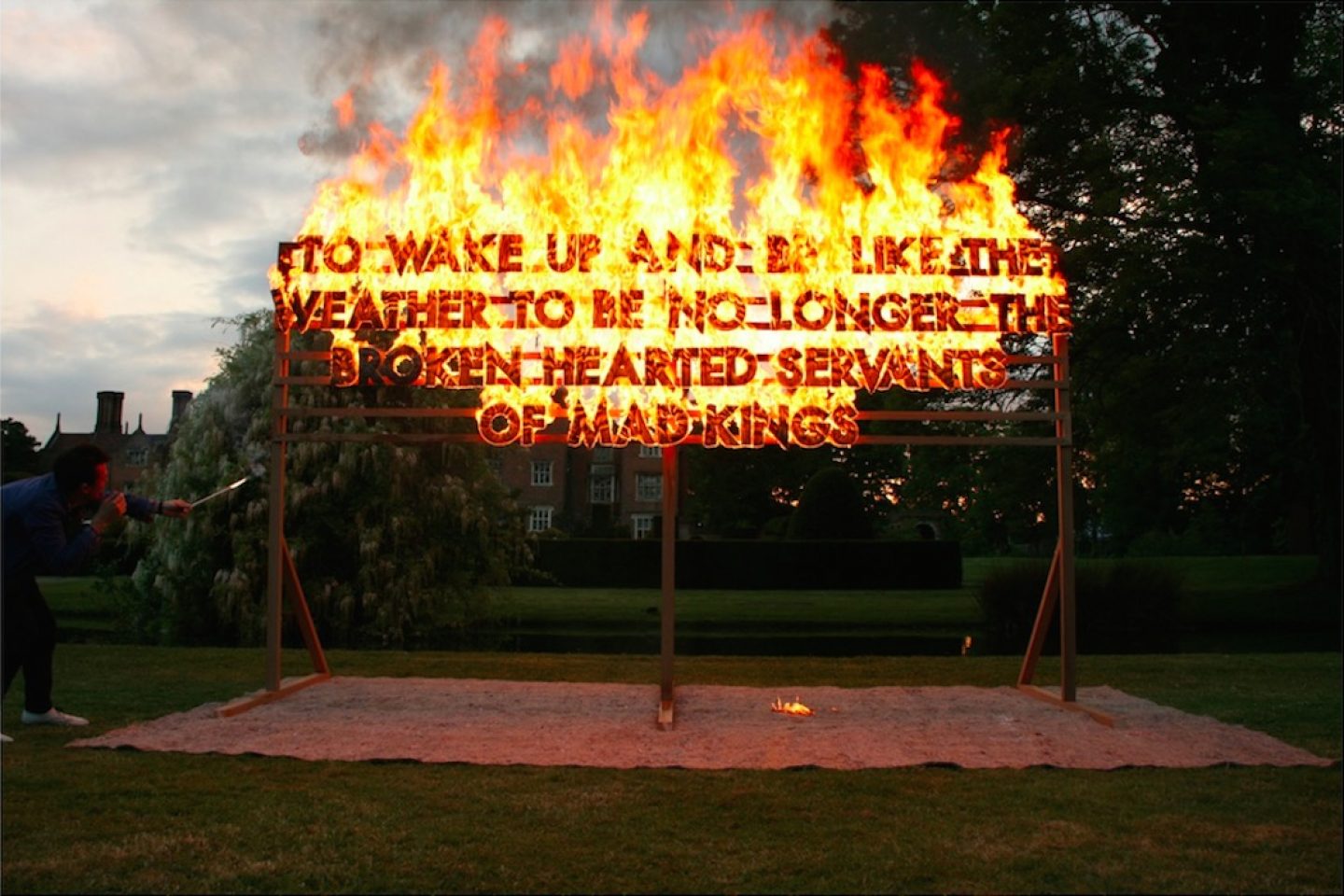

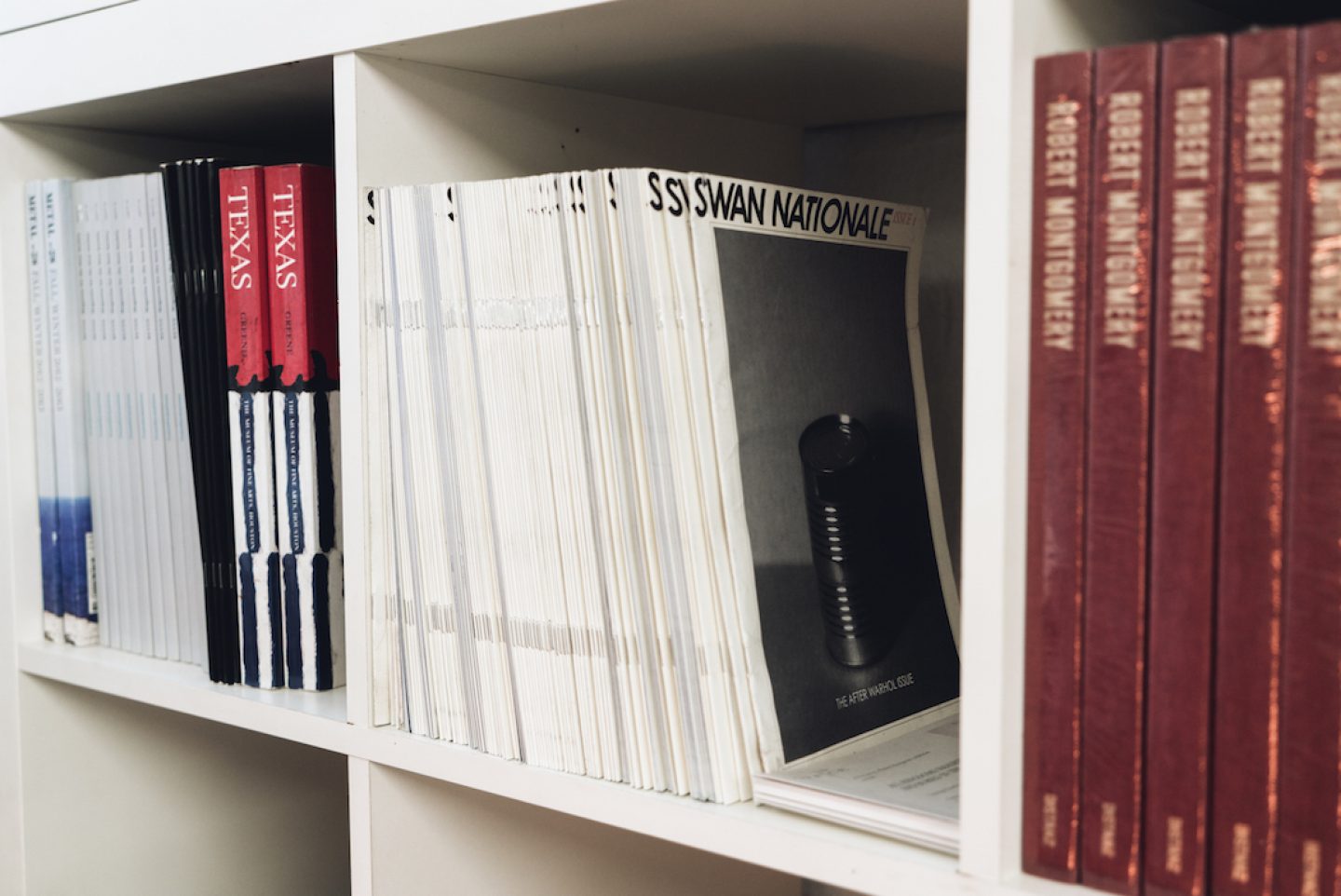

Best known for his fire pieces and light installations and billboards, Montgomery also works with woodcuts and watercolor, combining his formal training in fine art with his evocative, melancholic texts. One of his latest ventures has seen him and his collaborator in life and work, the poet Greta Bellamacina, launch New River Press. Conceived as a platform for ‘new language for sad times’, the press is the first London-based publisher of poetry founded in years.

With a recently-published monograph, several upcoming exhibitions and even more collaborations on the go, Montgomery’s schedule is as relentless as ever. We paid him a visit in his London studio, where we found him working on his “London-Paris Love Letters” series, a mail art project created in collaboration with artist Jean-Charles de Castebajac, which opens on May 19th at The Store at London’s Soho House. Over a cup of tea, we caught up on his latest projects, his shifting perspective on Europe, and his advice for those whose careers in the creative industries are just beginning.

The last time you were featured on IGNANT, it was 2012, and you were in the process of installing your first German exhibition at [the former airport] Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin. How would you say your artistic focus and practice has evolved since then?

I don’t think it’s really changed. I mean, the Tempelhof project was really important for me. It was with a Berlin-based curator called Manuel Wischnewski, who runs Neue Berliner Räume, which facilitates art projects in previously unused spaces. When I started working with him, he said, ‘Just come to Berlin and tell me the place you’d like to work the most in the whole city’.

“I wanted to work on one of the baseball scoreboards at Tempelhof because they were built by the US military, and I wanted to do a peace poem on military hardware.”And I wanted to work on one of the baseball scoreboards at Tempelhof because they were built by the US military, and I wanted to do a peace poem on military hardware. He did an amazing job of getting permission for that. Since then, my focus and my practice haven’t really changed. I still like to work with the history of a place. Last summer, we did a project in Seattle, Washington State, where we worked with a whole city block that was empty and about to become the power station for Seattle City Light. I did a whole series of billboards and one big light piece there taking an ecological perspective on the electric city, beginning by subverting something Ezra Pound wrote in the 1920s.

I kind of stayed with the theme of ecology at the end of last year. I did a bunch of projects around the COP21 conference in Paris, and I did a solo show in Paris with my gallery there, Galerie Nuke. I did a kind of participation in the official art element of COP21, called ARTCOP21, and then I participated in a completely illegal guerrilla show – Brandalism – with a bunch of artists who took over space in Paris to convey a stronger, more political and hardcore ecological message. I feel like I’m in a period of a natural focus on ecology, as I think the crisis is looming larger and coming faster every year, and we’re doing as little as we were doing a decade ago. That’s a frightening picture.

I think you can’t be making art at this time and not be engaged with that question in some way, unless you’re a coward, or selfish [laughs]. I’m doing a project in August for a Biennale in the south west of France, La Littorale, curated by Barbara Polla and Paul Ardenne, the French curator who curated the Luxembourg Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. The Anglet Biennale has an ecological focus, and I think the art community of curators and artists that I feel connected with at this point is coming more and more to that question, and we all have to inevitably.

A selection of light and fire poems. All images © courtesy of Robert Montgomery.

So much on the go! Can you speak to us about the project you’re working on today?

Today I’m working on some drawings that are collaborative, with a really good friend of mine in Paris, the artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac. We’ve been friends for a long time. I think we actually met at Malcolm McLaren’s funeral. When I had a studio in Paris part-time, we hung out a lot. Since we closed the Paris studio and I moved back to London, Jean-Charles and I have been doing these correspondence drawings. So I begin the drawing with a poem in London, FedEx it to Paris, and he begins with visual drawings in Paris and FedExes them here. Then we do a little bit each and send them back. It’s a really nice thing – kind of a mixture of Exquisite Corpse and Mail Art. We’re doing a show of these called “London-Paris Love Letters”. It opens May 19th at Alex Eagle’s new space in Soho in London. It’s owned by the same people who have The Store in Berlin’s Soho House building.

“I begin the drawing with a poem in London, FedEx it to Paris, and he begins with visual drawings in Paris and FedExes them here. Then we do a little bit each and send them back.”And then I recently finished a really big public piece in Izmir, a very ancient city in Turkey. It’s mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey, in the context of the relationship between the sea and the city. It speaks about the sea dreaming the city as a kind of motif. And then I’ve been invited by the Opera House in Brussels, which is at a very, very nascent stage. The composer is called Anat Spiegel – it’s a reworking of the Orpheus myth: Orpheus coming back from the underworld. She wants to focus on the part of the story where Orpheus comes back lovelorn from the underworld, having failed to save Eurydice. In the ancient text, they talk about his grief singing – the sound of his grief changing the weather, changing the trees, changing how the animals behave. So it’s about elemental scale love grief.

She’s a contemporary composer, and she wants to use the text of my poems as the libretto – the text, the lyrics of the opera. I’m currently compiling everything, which will then become the source material for the composer to select text from and write the music. It’s a really interesting approach to opera, which has quite a classical form, without using historical opera music and historical libretto text. So the text is my work and the music is hers. It’s going to be really interesting, I think. It’s not necessarily a medium I ever thought about working in.

I’m interested in your writing process in general. From short poems to grand-scale operas – how do you start a new project?

“It’s kind of a melange of poetry and text art, what I do, in a sense. I want it to sit awkwardly between the two practices and be neither wholly defined by one or the other.”Everything starts with the notebook poems I’ve been writing since I was a kid. I always wrote poetry privately, and then studied visual art, and at a certain stage, I studied Lawrence Wiener and Jenny Holzer – who are text artists I love from past generations – I got to the point where I couldn’t see any reason not to bring poetry into that form. So I experimented with that.

It’s kind of a melange of poetry and text art, what I do, in a sense. I want it to sit awkwardly between the two practices and be neither wholly defined by one or the other, so that my work makes a space for itself in between text art and poetry. I’m interested in that space, that borderline. I’m really into collaborating at the minute too – I’m writing some poems with Greta Bellamancia, a young London poet with whom I started working organically. Then I’m doing the drawings with Jean-Charles, which are collaborative. Then I have an ongoing art and fashion collaboration with Each x Other in Paris. And I’ve just started a small poetry press in London called New River Press with a bunch of London poets whose work I believe in.

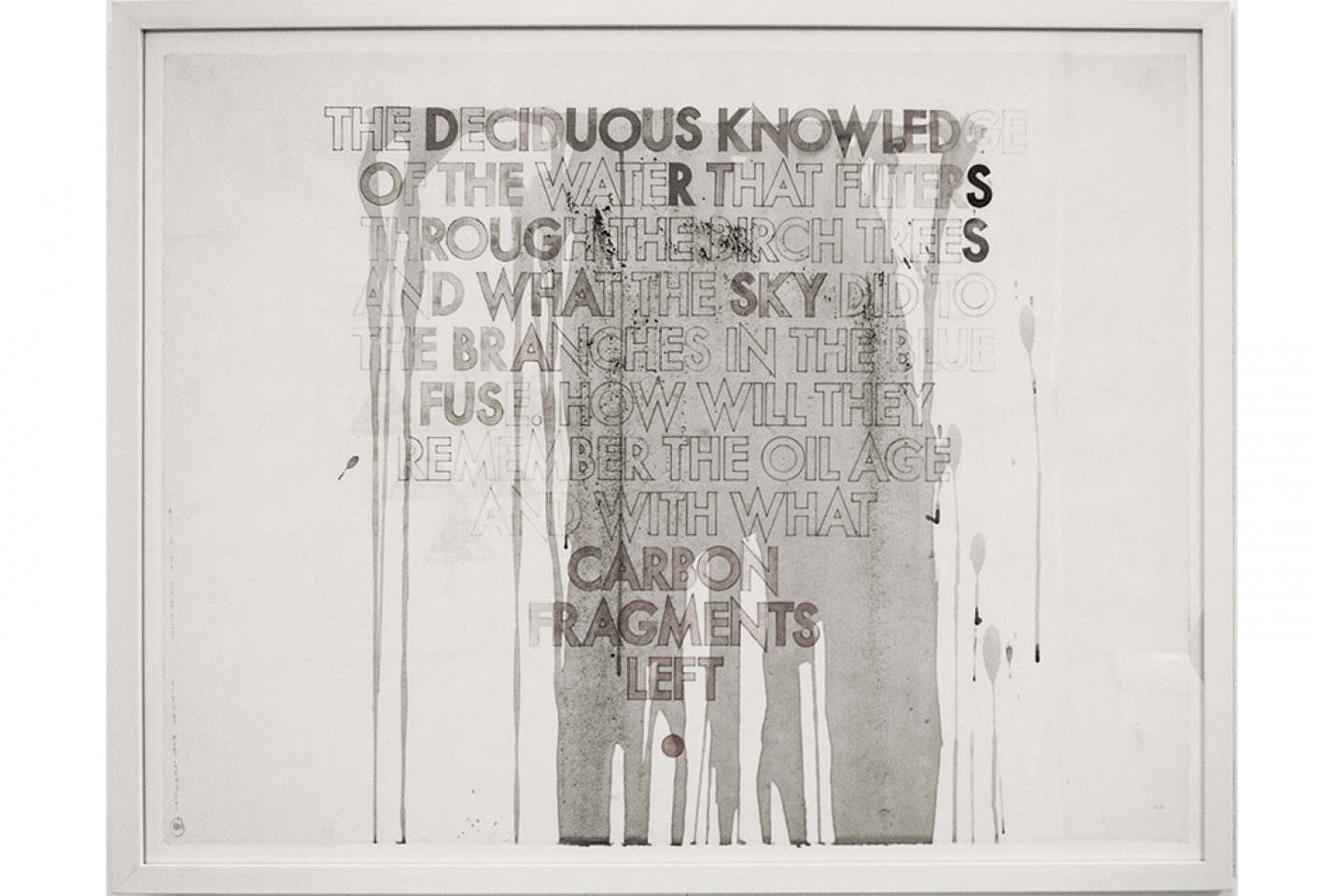

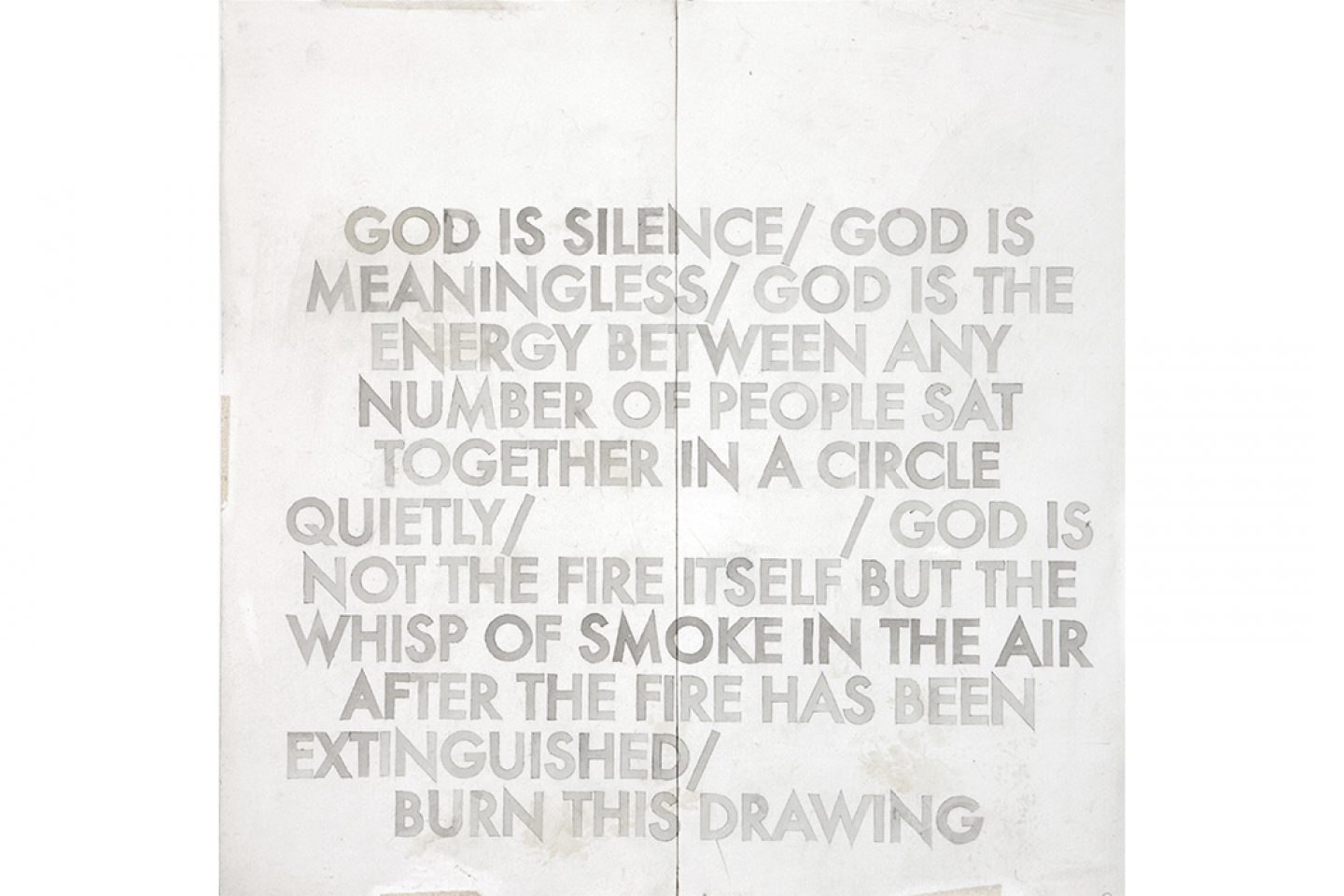

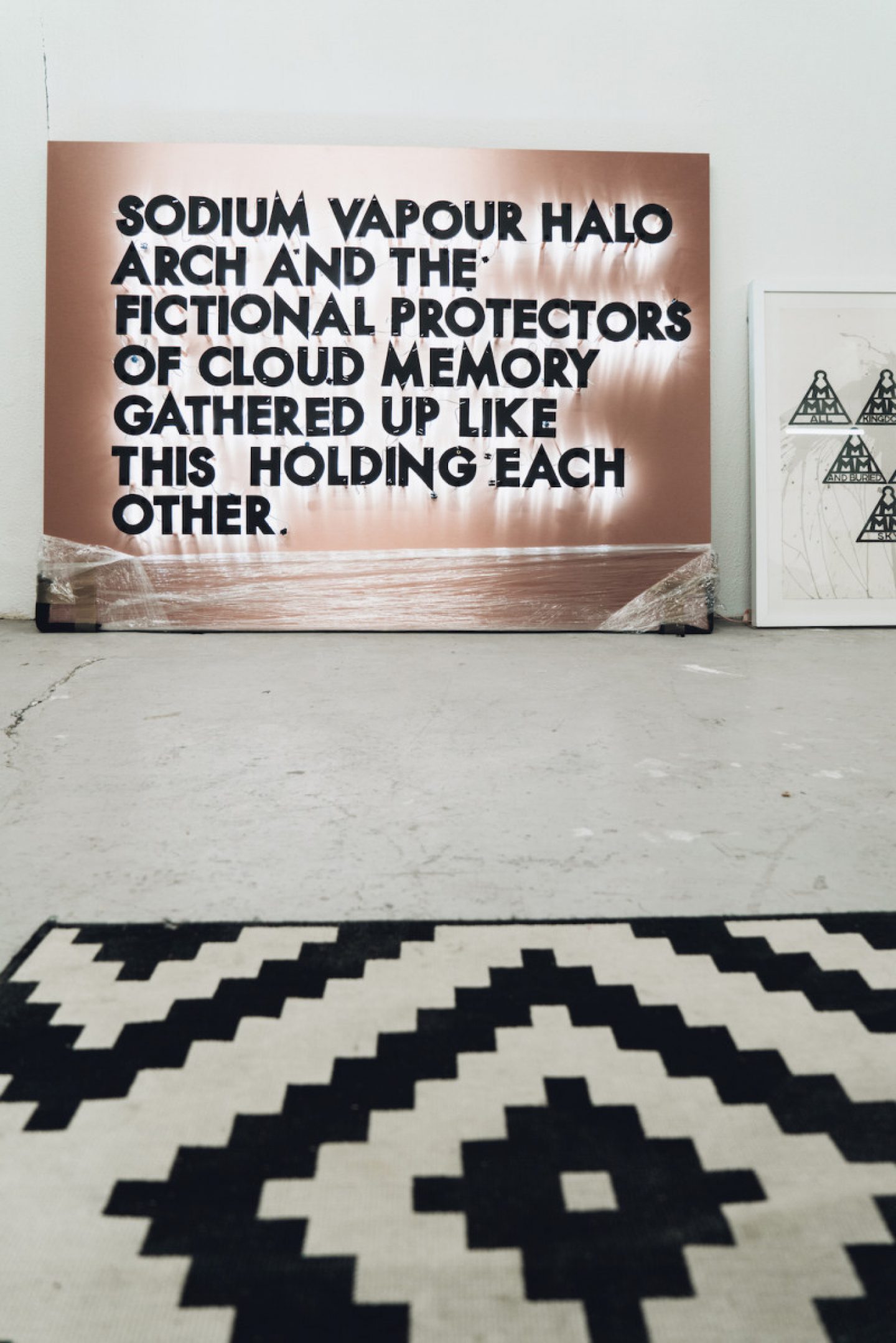

But when I start out with studio practice, I really think about the basic elements of mediums and practices. I start with the texts that are kind of poetry. I studied painting, so I think about drawing, and also print-making, a lot. So these drawings [points] are watercolors – there’s a whole series of those. I’ve always loved watercolor, as it’s quite a trite 19th century English amateur painter medium, and I’ve always wanted to use it as a contemporary art medium. So I go back to watercolor constantly as a reflective practice, in a sense.

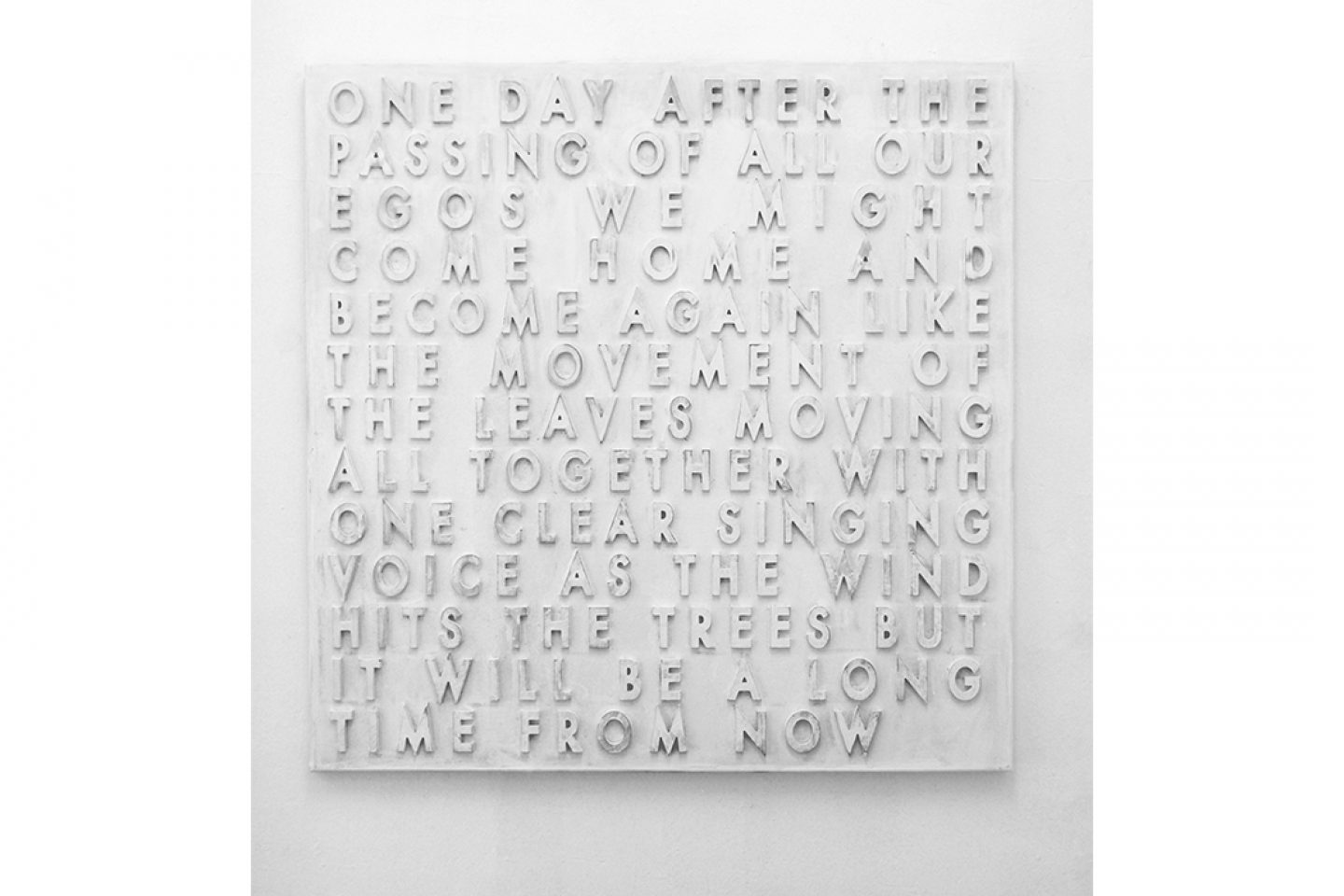

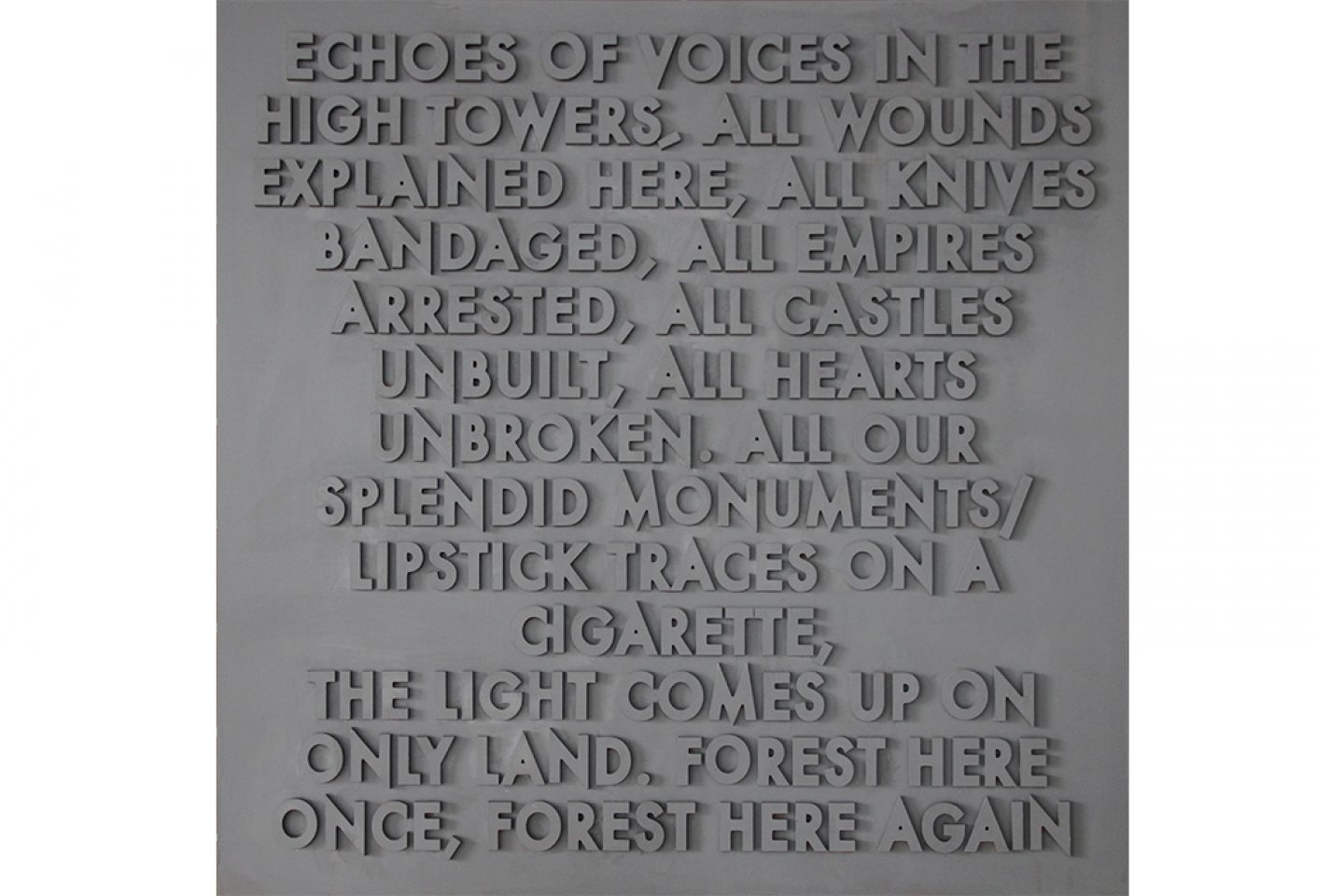

I’ve also ended up with these positive woodcuts, which are pretty much the basic formats of the woodcut panel – quite a Germanic tradition – where you carve into the panel, ink it, and then you make the productions in negative. I did that a lot at college, but I always liked the object more than the prints they’d make, so I decided to make works from just the panels. I call them woodcut panels as they’re an inversion the of the traditional printmaking process. We’re currently experimenting with whether we can use the acid etching printmaking technique to make metal letters that are degraded by acid, and end up looking slightly relic-like, degraded, which is another inversion of a printmaking technique. And that kind of dovetails quite well with the ecological themes in some of the writing I’ve been working on.

A selection of watercolors, drawings, woodcuts and LED works. All images © courtesy of Robert Montgomery.

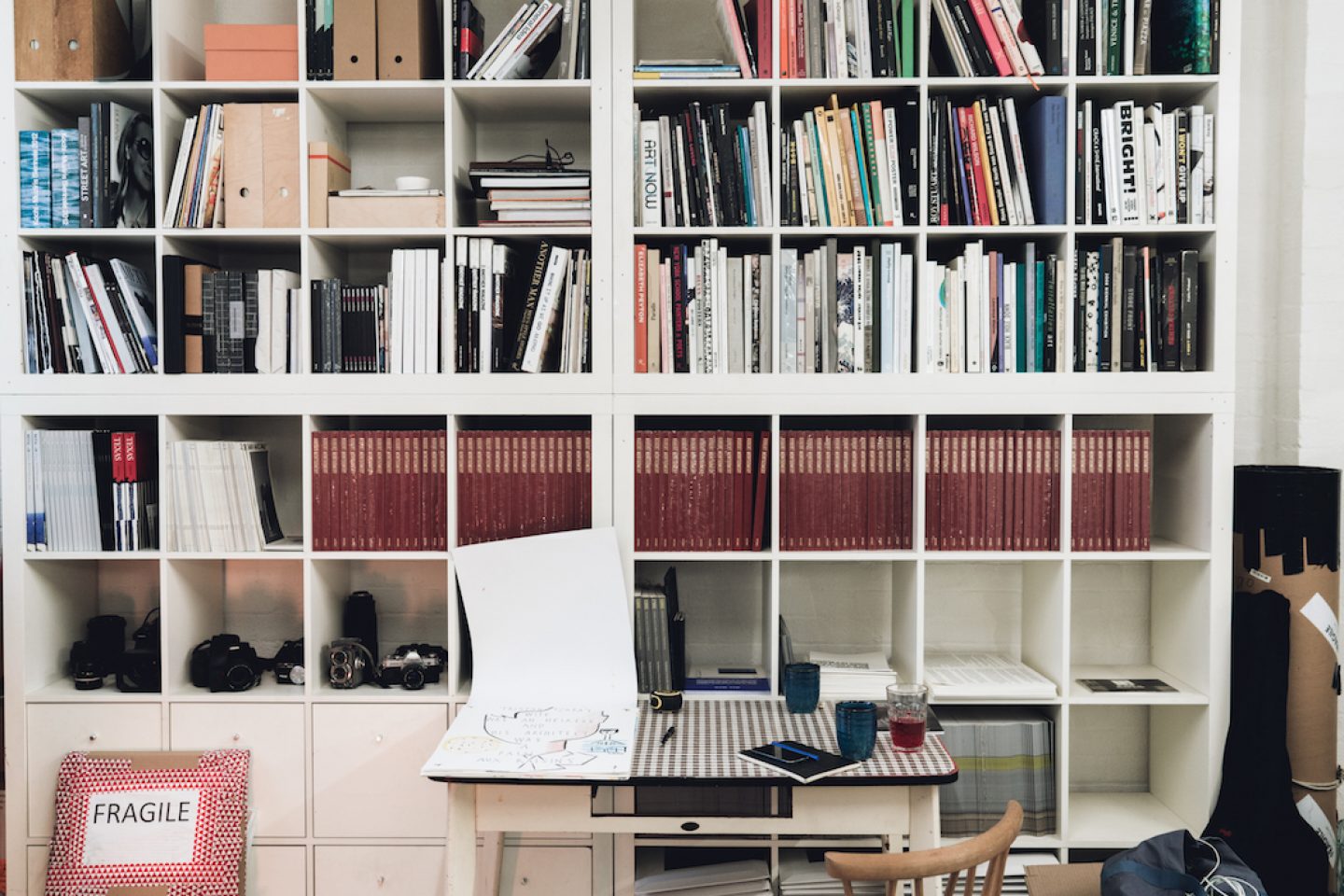

You’ve recently moved into a new studio, located in the Tannery Arts Centre in South London. How did you come to have your studio here, and what are the most important elements of a workspace to you?

“In London, it’s become a question of finding buildings in transition to use as studio space, otherwise it’s impossible for artists to find big spaces like this.”So it’s getting harder and harder to find space in London, as we’re in the middle of a crazy property bubble, I think – I mean, I had my Shoreditch studio for six years, then the lease was up for renewal. The landlord increased the rent by 68 percent from one month to the next. So I left. The space I’m in now belongs to an artist group called Tannery Arts, who have been in this neighborhood, SE1, for a few years, and they’ve just got this building.

Sean Gladwell, the Australian artist, a friend who shows with my gallery in Geneva – Barbara Polla’s Analix Forever Gallery – is also in the building, so there’s a nice little community for me here. Space is really the only thing that’s crucial, and this is a pretty industrial space. This building was an old factory – it’s in limbo between that and becoming something else in a couple of years. In London, it’s become a question of finding buildings in transition to use as studio space, otherwise it’s impossible for artists to find big spaces like this.

This leads into one of the driving themes of your work, post-Situationism. What relevance does the Situationist International movement have in today’s urban context?

Broadly speaking, I think Guy Debord predicts the nightmare really well – of the way that capitalism will reduce the types of discourse available to us, and our mental space, and encroach more and more on our free time, our thinking time, and our dream time. I think my fascination with Debord has always been because he takes that question and applies it to the interior person. So it’s not just a materialist Marxist critique, it’s a real look at what capitalism does to the child inside of you – to your interior life. So the avenue of enquiry remains as valid as ever.

It’s a pretty depressing situation if you just look at it through Debord’s lens, I think. I have to find more hopeful examples. If you look at what Debord writes in the 1980s, like the book “Panegyric”, which is his memoir, I think he ends up being a very depressed person as he feels he’s lost his war, and in the end I think it was a war for him, one that he would win or lose – and he felt like he lost, right? If you look at other writers in the tradition during the ‘80s, like Hakim Bey, in him you see a more playful approach to finding pockets of freedom in contemporary life that remain “Temporary Autonomous Zones”. Bey’s idea of freedom and where you can find it, I think, is hopeful.

A selection of billboards across London, Berlin and New York. All images © courtesy of Robert Montgomery.

One place that has been associated with a sense of freedom – over the past couple of decades, at least – is Berlin, where your work has often been exhibited (Tempelhofer Freizeit, and Stattbad Wedding for example). Can you speak to us about your connection to the city?

Well, I’m coming back to Berlin to do an exhibition with Anna Lüpertz in July. I’m excited to be coming back to Berlin in summer, having done my last works there in winter. The city is so beautiful in July. [Picks up and flips through his monograph] There are a bunch of Berlin connections to this book, which is published by [Berlin-based publisher] Distanz. The introduction is written by Douglas Gordon, who is a Berlin-based artist. He wrote his first ever poem as the introduction, which I love – I managed to get him to tap into his inner poet, which isn’t so far below the surface at all with Douglas. In a sense, this book is made in Berlin, so it’s interesting, actually. It’s my first monograph, and it was completely initiated by Anna Lüpertz and Henrik Wobbe, one of her collectors. They had the idea, and made it happen with Distanz.

I think Berlin represents a space of freedom that London increasingly doesn’t have, simply because we haven’t managed to protect the creative community in London with any reasonable rent control, and Berlin is doing better from that point of view. I feel as though I just made it in terms of being able to survive as an artist in London, but I don’t see how kids of 20 these days can do it actually. So I think the future in terms of art in Europe is probably going to come from the cities with affordable rent. London has to deal with that, otherwise it’s going to become a cultural desert. And I wonder if in ten years, we’ll see the most creative work happening in places like Warsaw and Bucharest. I wouldn’t be surprised. I’m quite fascinated in repositioning our perspective on Europe, I think it’s been really Western-Europe centric.

“I feel as British people in Europe, we really focus on this Anglo-centric tradition, and I have so much to learn about European poetry that’s not in the English language.”I’ve been working with some creatives out of Bucharest in Romania, who have this project with the really old Viennese coffee brand, Julius Meinl, and they had this historic relationship with Viennese writers, which goes back to the 1860s. And they’ve started this program of working with a poet every year. I’m their poet for 2016 and that’s been really interesting, as I’ve been going to Vienna and Romania with them, and gravitating back to central Europe.

In a sense, Berlin is the center of Europe, and London and Paris are the western edge, right? So with Berlin you get a sense of wider Europe. And in Romania, or Bucharest, I really got this sense that what I’d always thought of as Eastern Europe is really Central Europe. Bucharest and Vienna are really central Europe, and we kind of have to re-orientate our longitudinal perspective on that. I’m quite fascinated with this project, to see what I discover about poetry traditions in Europe which are non-English speaking. I feel as British people in Europe, we really focus on this Anglo-centric tradition, and I have so much to learn about European poetry that’s not in the English language. I think Central and Eastern Europe have a lot of creative potential.

Who – or what – else is currently inspiring your work?

I’ve been immersed in the work of this really great Irish poet called Niall McDevitt, who’s been involved in restarting [Situationist International newspaper] the International Times. He’s a profoundly good poet with an incredible depth of vocabulary, and he also does psychogeographical walks tracing the literary history of London, which are incredible lectures in the street. We’re publishing him with New River Press. I’ve been looking at 10th Century English tapestries which I’m subtly referring to in some drawings I’m doing for my show at Anna Lüpertz, and I’m upset and ashamed that Britain hasn’t taken our fair share of refugees from the Middle East crisis so I’m making some billboards in London with a “refugees welcome” message. I think as a country we have to show much more compassion and open our hearts.

Finally, do you have any advice for young people working who are just starting out in their careers within the creative arts?

I mean, the only advice really is to keep going. Because what defines whether or not you become an artist is probably not how good you are coming out of art school. It’s how bloody determined you are to keep going for the next 10 years afterwards. And I think you have to come out of art school with the determination to go at it alone for a decade if you have to, get a day job, work in the studio four nights a week, put in the hours, don’t give up, keep going with the struggle, and that’s it, man. It’s like 10% inspiration, 90% determination, pure grit, and heart.

"Put in the hours, don’t give up, keep going with the struggle, and that’s it, man. It’s like 10% inspiration, 90% determination, pure grit, and heart."

The interview was edited and condensed. All text and images (unless otherwise stated) by Anna Dorothea Ker.