Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee · Berlin, Germany

- Name

- Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee

- Location

- Berlin · Germany

- Images

- Clara Renner

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Elegant architecture can be hard to reconcile with the darkest era in a country’s history. Yet this was precisely the challenge faced by the architects Andreas Veauthier and Dr. Nils Meyer with the restoration of the ‘Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee’, a swimming pool located in southern Berlin.

“The design was considered highly modern and elegant both for its time, and still is today.”Originally designed by architects Karl Reichle and Karl Badberger as a paragon of Nazi architecture, the pool opened in 1938 as a physical training facility for the SS Leibstandarte, the personal bodyguard division of Adolf Hitler. Despite its distressing origins, the design was considered highly modern and elegant both for its time and still is today with its lofty windows and Neoclassical proportions. We sat down with Andreas Veauthier to find out more about and the challenges of restoring a warm, humid space, the struggle to save historical buildings from demolition, and the role of an architect in coming to terms with a building’s troubled past.

Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee is not the first swimming pool that you’ve worked on. How the architectural design of swimming and sports facilities in Berlin come to be one of your areas of specialization?

The question of specialization is always a tricky one, because at a certain point, you simply come to have certain areas of specializations. It’s not like you say, “now I want to become a specialist in swimming pools”, but rather you do your work, and the credentials you earn eventually turn you into a specialist. The key point is those credentials.

“The pools we’ve worked on represent an incredible type of architecture, one that’s becoming increasingly rare today.”What particularly interests me about working on swimming pools is that they are public spaces. They’re big open rooms that play host to many people. In comparison to say, an office building, they have much more foot traffic – people who come to swim because of the architecture, perhaps. The second thing that comes to mind is that we work on existing public buildings of a certain caliber. The pools we’ve worked on represent an incredible type of architecture, one that’s becoming increasingly rare today. Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee represents a very modern style of architecture. It’s an unbelievable space, and so to be able to work on it was an incredible opportunity.

What are the specific aspects when working on a swimming pool? What makes it different to the refurbishment of other types of buildings?

That’s an easy one: A swimming pool is very warm and very humid. So each element of its construction is under constant strain. Every element that is built – be it wood, plasters, or stone – must be able to withstand a lot of moisture and a lot of heat over the decades. This is what distinguishes swimming pools from gymnasiums – which are cold – or town halls, which vary between the warm and the cold. The whole task takes on a whole new dimension when you’re working with historical buildings, say 80- or 100- year old surfaces, which still need to be able withstand heat and moisture today, whilst many pools built in over the past 20 years are already in decay.

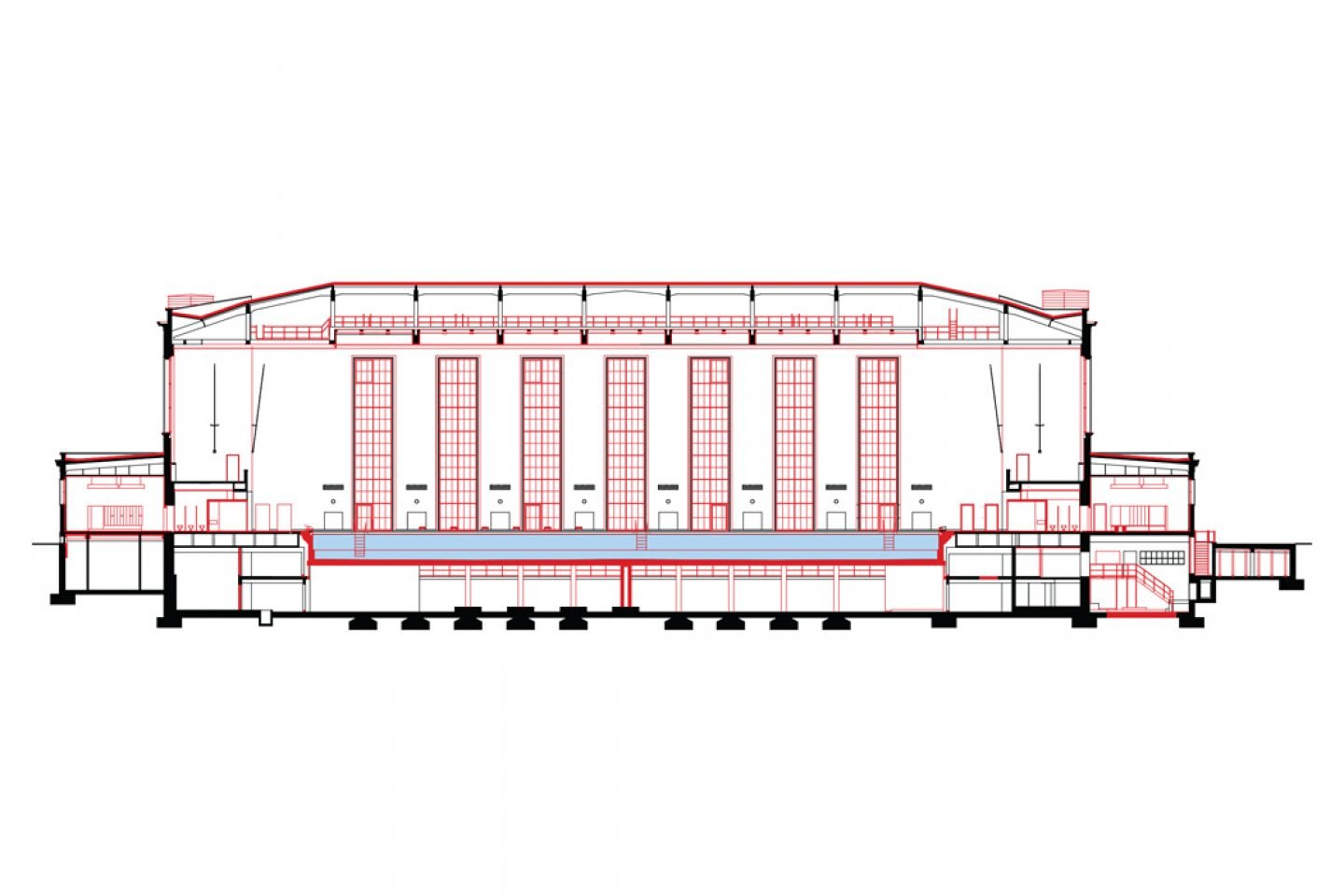

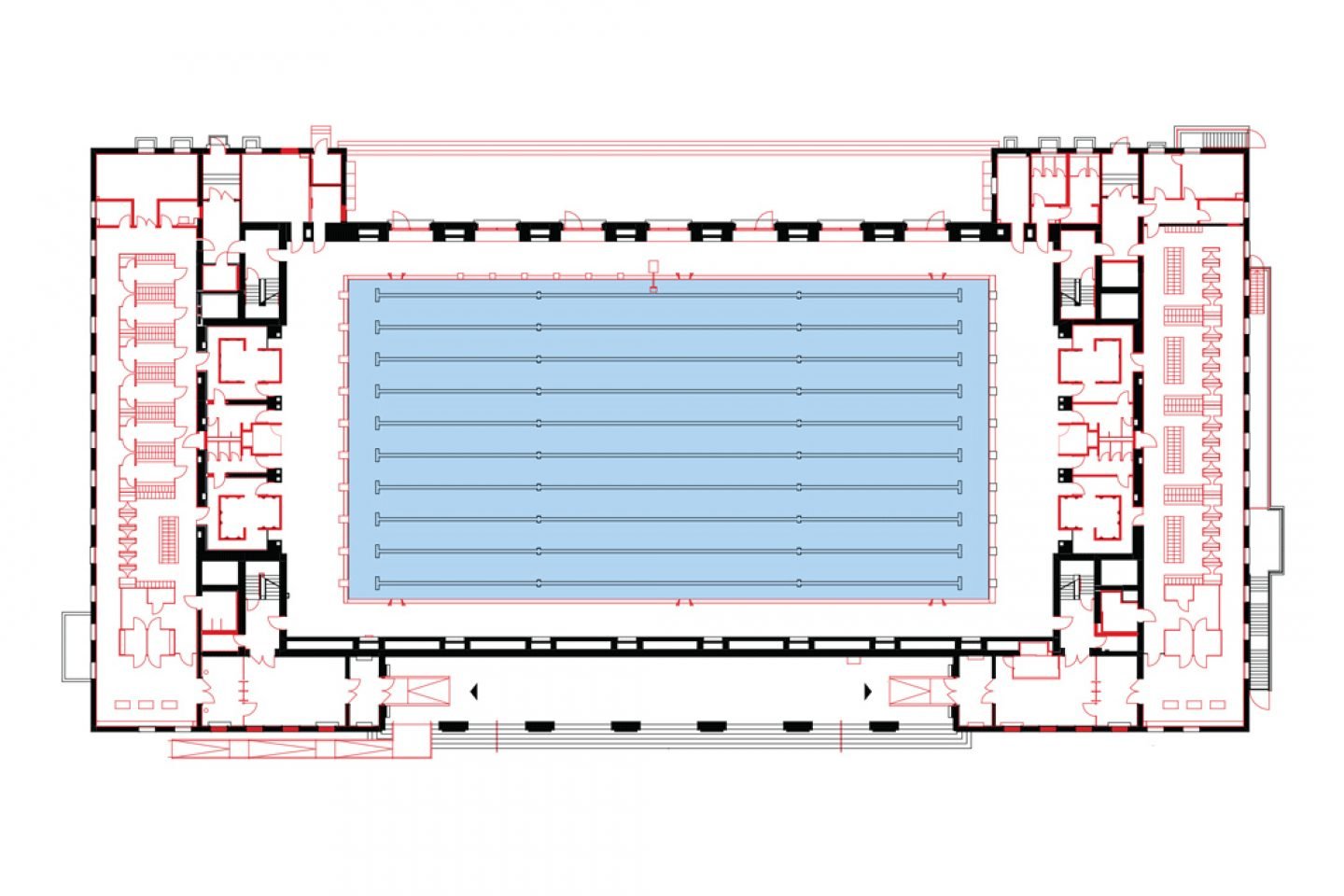

Floor and section plans of Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee.

Which element of the project did you find to be most challenging?

“The big task was to work with these limitations to recreate the original cellingThe most challenging aspect was the ceiling.”There used to be a large, bright ceiling that let daylight flood through, but we couldn’t rebuild it in its the original style as the roof was badly damaged. The ceiling that was inserted by the Americans when they took over the building after the war was a white drop ceiling – it was so hideous! The big task was to work with these limitations to recreate the original celling, without allowing direct daylight through. The work we did on the windows was also very interesting. And we completely replaced the pool itself – it used to be five meters deep, and was destroyed. Our main task was to build a new pool with a lot less water, in order to save energy. We also had to consider the acoustics, which hadn’t been taken into account in the past, not to mention ventilation, which is very complex, especially when working on historical buildings. Since September 2014, the pool has been – for the first time ever – barrier-free: Fully open to the public, to both genders, and accessible via wheelchair.

Could you tell us more about the hall’s original architecture?

“That is of course the challenge: How do you go about democratizing such a building, opening, making it accessible to the public?”Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee was built in 1930s and originally served as a physical training facility for the SS Leibstandarte, as part of a large military complex in the south of Berlin. It was built very quickly, without a paragon at that time. Well, there’s a very modern pool from the 1930s in Gartenstraße, Mitte, but Finckensteinallee was the largest swimming pool in Europe of its time. It was built solely for men, given that the soldiers were all male, and it was created as a utopia for fitness. The ten-meter diving board set the scene, and – for the 1930s – the building was extremely modern, due to its integration of highly technical features. For example, even today the cellar contains ventilation systems that you can walk through – they’re as large as a two-family house.

For me, the architecture isn’t ‘Nazi architecture’, as in, conservative. Yes, the hall was built by Nazis for Nazis, but today fewer Nazi elements remain – and that is of course the challenge: How do you go about democratizing such a building, opening, making it accessible to the public? It’s not easy. We approached it by focusing on the important elements of its architecture – the precious stones, the construction of the windows – and went about restoring and refurbishing these.

Can you elaborate on your approach to the uneasy historical background of the building? What do you think is most important for an architect when dealing with the architecture with such a difficult past?

“I think the most important thing for an architect facing such a challenge is not to lie, not to suppress the past or turn away from it.”I think the most important thing for an architect facing such a challenge is not to lie, not to suppress the past or turn away from it, but rather respect the original characteristics of the building. We didn’t transform it into something else, because we didn’t overrate or place too much importance on the characteristics of a Nazi building. For me, it’s a modern 1930s design. Of course, the dimensions hark back to a certain time – you can compare it to the departure hall of [the now defunct] Tempelhof Airport, for example, which is also a particularly beautiful space – but it’s not like we built the place anew, it doesn’t represent my style of architecture. If we built it from scratch, it would of course be totally different. But our task was one of restoration, of which I fully understand the purpose, because it’s a testimony of the architecture of its time. As architects, our contribution was to ensure that nothing was misplaced or put aside: That it remained intact as a testimony. It’s doesn’t represent the Nazi architecture of 1945, but instead the very early Nazi architecture of 1936, that – as a typology of a sports facility – was not dictatorial or manipulative. It’s principally a bright, transparent and modern example of 1930s architecture, and one that was completely justifiable to refurbish.

Berlin is a city with a layered history and an eclectic architectural landscape. Are there any other recent renovations of historical buildings that you find noteworthy?

I think we’re living in a moment in time in which we misunderstand history, in which we haven’t yet come to terms with it. On the one hand, we have many memorials that aren’t restored, as the ‘public domain’ says there’s no money for it, and on the other hand, we have new buildings that are designed completely eclectically, even in historical styles. Many new apartment buildings look like they were built 100 years ago, without the quality and integrity that existed at that time. In this respect, we approach history in a complicated, burdened way. The imbalance is highly prevalent in Berlin, though it hasn’t always been this way, looking back over the past two decades. Up until the turning point, we took a very modern, avant-garde approach to history, to historical structures, and then came the turning point and the critical reconstruction of Berlin, where it was said that Berlin is ‘almost there’, we just need to complete it.

“We don’t have the money to preserve our own heritage – take the Olympiapark Schwimmstadion, for example.”At this time, all questions of ‘how could we do it differently?’ were ignored. And from this eventuated the architectural tendency towards the conservative, which set the direction of the city’s evolution. Today we’re at a point where we have a very repressed, burdened approach to history. We don’t have the money to preserve our own heritage – take the Olympiapark Schwimmstadion, for example. This city is full of incredible historical buildings that are partially in decay, as we’re not restoring them. Therefore I saw it as very important that the Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee was renovated, because I think Berlin is the swimming pool capital of Europe: We have many designs and it makes sense to restore them, as there are hardly any more of their kind them remaining in Germany. We have the Olympic Stadium from the 1970s in Munich, and in Wuppertal there’s the Schwimmoper from the post-war years – but we have very few remaining large swimming pools in which the public can swim in today. Here in Berlin, it was hard to convince the Senate of Berlin that it was necessary to renovate the Schwimmhalle Finckensteinallee. It was too expensive. “Why can’t you tear it down and build it again, much smaller?” They asked. We replied, “No, it’s a monument. It can’t be torn down, and neither should it be – it’s beautiful.

The interview was edited and condensed. Text by Anna Ker and Monika Mróz. Photography by Clara Renner. Plans © Andreas Veauthier & Dr. Nils Meyer.