On Making Spaces Matter with MeierHug Architects

- Name

- MeierHug Architects

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Together with Zürich Tourismus, we recently visited Michael Meier and Marius Hug of the renowned Swiss architecture practice MeierHug. From their freshly renovated offices in an old pastry factory to a two-family apartment building constructed with minimal plans, we got inside their architectural brains, and in turn, they quickly won over our hearts.

Over coffee and under the eaves of the light, airy office extension that houses their studio, the duo shared their thoughts on trusting your gut instinct and making it up as you go along. They shared with us their considered—yet warm—attitude towards work, their frank approach to partnership, and their shared progressive vision.

You grounded your studio in 2001. How did you come to work together?

Michael: We got to know each other at Miller & Maranta in Basel whilst working on the same project. There we also got to know another architect from Davos, who asked us if we wanted to work on a project for him. We thought it’d be super interesting and said to ourselves, ‘Why not do the project in Zürich instead of Davos?’ This allowed us to have the opportunity to rent a small studio – in Kreis 3 on Werterstrasse. That’s where the project was born. It involved a study on the preservation of sites of historical importance. It went on for a long time, and was only completed five years ago: So a total of 10 years. Well, we found ourselves with a bit of extra capacity in the meantime, so we spent our spare time working as lifeguards over summer: Mornings at the pool at Badi Enge Lake, then we’d head back to the office to continue working on the project. At some point we started taking part in competitions. So our joint career started unfolding pretty slowly and sweetly, which was great because it gave us the time to get to know each other.

How would you describe the philosophy behind your practice?

“The competition culture is very well established here. Each week we can put ourselves forward for an exciting new project.”Marius: We haven’t formulated one particular philosophy to follow, but we’re less interested in loud architecture, and we work largely based on instinct. There are certain things that speak to us. We also have mutual control over out work – so sometimes one of us will say, ‘Hey, this isn’t working’. We’re also very locally grounded. We try to draw upon our experience of the environment that surrounds us, which isn’t very big. Something that perhaps defines our direction is that we want to work with the widest possible range of projects. We’re often interested in smaller conversions that require historical preservation – but we also like working on larger projects. Bridges are of interest to us, but we’re equally happy creating a small outhouse. Switzerland is a great place for this variety. The competition culture is very well established here. Each week we can put ourselves forward for an exciting new project. Initially we focussed on the field of elderly care – so retirement homes, as there were fewer competitors in this field and so of course higher chances of winning. Our first big project was actually a retirement home.

We’re sitting here in your newly renovated office. Can you share a bit about the renovation, and in particular the extension?

“The building was originally a factory that prepared ingredients for pastries – it was called the ‘edible fat factory’.”

Marius: The building was originally a factory that prepared ingredients for pastries – it was called the ‘edible fat factory’. Sugar, fats, glazes, butter and Switzerland’s first nougat were prepared here. We were originally tenants in the floor underneath the one we’re now on. Two years ago there was a fire in the cellar of the factory. The smoke filtered through to our floor so we had to get out while the whole place was cleaned for three months. The silver lining of this incident was that we got to know the owner of the building. He has deep roots here, as one of the grandchildren of the company’s founders. The owners already had renovation plans, and we said we’d love to stay in the building, but needed more space. Michael then sent him a sketch of the roof extension, which he found to be a very strong idea.

He liked the fact that our proposal wasn’t about remodelling the space by packing on more insulation and then sticking a window on top – instead, we wanted to preserve the original character of the space. This was also clever as the roof needed renovating in any case as it was leaking, so we were able to pitch our renovation and expansion within the budget that was already going to be spent on fixing the roof. That was of course ideal for the owner, as it gave him both a fresh renovation and also additional space to rent. For us it was equally satisfying – we know we can stay here for the next 20 years, and even make the office space a little smaller if we have to.

Do you always work together on projects?

Marius: Yes, we have a strong starting point. A competition runs for 8-12 weeks, and in the initial phase, we go through everything together. At this point we engage in a lively exchange where lots of sparks occur. After this phase, we split up. Because building owners usually want someone to attend every meeting, we divide the work between us, but always consult each other in between. It’s really important to both of us that we each have a sense of what’s happening. Of course we don’t know every single detail of every project. But we still have the feeling that we’re a tight team.

What do you do when you’re not on the same page about a project?

“If someone says, ‘That looks like it’s always been there’, that gives us the feeling that we’re doing OK.” Marius: That’s rarely the case. But of course it’s not so great when it is. I have the feeling that we have very similar approaches and if something bothers one of us, the other one will try to reconsider their position, and this usually works really well. I can’t think of a single situation where we both decided we couldn’t move forward. Of course there are challenging confrontations – it’s like a relationship, right? I think we both give each other the freedom to say, ‘Well, I would have done it a little differently…’ but it’s perfectly fine that way.

Michael: It’s absolutely not a charged process – taking the example of Haus Albisrieden, of course at the end we’d both have done a few things differently looking back, as we’re in a different headspace to when we were all in it. That’s also apparent with the teams we have – we don’t always lay out the entire plan for them. We like to let projects evolve naturally. Not everything has to be fixed from the beginning.

Marius: We don’t always know exactly what the best solution will be when we begin. As we start to work, we let ourselves make decisions as we go: Is it round? Square? Thin? And then we run with our decision and at some point we decide on a certain path and apply that choice. Sometimes this works better than other times, but every project becomes a memorable one for us and will contribute somehow to a future project. We have certain approaches and directions that interest us, but no set way of working that we can easily describe.

Michael: So often it comes down to our gut instinct. There’s no theoretical guidebook that dictates our work process and says ‘This is the only possible way in which it can evolve’.

Marius: The kind of architecture we’re involved in isn’t so existentially reflective, so we can approach it in a relaxed way. There’s not one truth we’re searching for. Of course the designs should look beautiful and be relatively timeless, so that they don’t appear dated 15 years later. Instead, they should add value to the place. That’s what we aim for. If someone says about our work, ‘Ah, that looks like it’s always been there’, that gives us the feeling that we’re doing OK.

Can you fill us in on your ‘Haus Albisrieden’ project?

“The kind of solutions we needed to find required the work of a psychiatrist!”

Michael: I grew up in Albisrieden and went for a walk there one day. I passed by an empty lot that piqued my interest. Three to four months later, the plot was on sale online for an absurdly high price. It took half a year of negotiations before I bought the properly. The difficulty was that Albisrieden is not in the most noble part of Zürich, so you need to build a lot relative to the plot size to make it worthwhile. As a single family home was out of question for this bit of land, we thought a two-family home would work better – to offer either as a rental or for sale. We then had one year to obtain approval – only then could we complete the purchase of the land. In the past it could be bought with one payment outright. We had to fight it out along with two or three other competitors.

Marius: It was a very long plot, but we could only build on one part of it. There was a constant back-and-forth regarding maximum building height, because the plot was in a two-story residential zone. This project was not a typical task of our office – rather exceptional. The kind of solutions we needed to find required the work of a psychiatrist, rather than that of an architect!

Michael: The project also went in a bit of a different direction than we first expected. We simply began without a clear timetable or construction plan. But it was always clear that there should be a concrete building, around 60% below the earth. It was a little dangerous, as we went ahead without the plans even being complete. But that also made it a really exciting process, as there was a lot of freedom from the construction managers. That was fine for us as it was our creation – otherwise it would have been impossible, really!

Is there a dream project you’d like to work on one day?

“A convent would be amazing [to work on]. Or the new Berlin airport.”Michael: A convent would be amazing [laughs]. Or the new Berlin airport [laughs again]. There is a museum in St Gallen. It’s a very particular task, as the space has a different function for the public. We hope that we might be able to deal with something similar abroad one day. We’re not often invited to participate in competitions in Germany, even if plans for museums are already underway. We have great respect for the German market, but we’ve heard from colleagues that it can be super challenging to work in, due to all the regulations. We wouldn’t say no to a more ‘exotic’ project either – say, in Brazil. The location – and perhaps also the construction process – has to interest us. It can either grind you down or propel you in an exciting new direction. We’ve been lucky in that respect – we haven’t yet encountered an experience that made us think, ‘Oh no, now we have to compromise to keep the office going’.

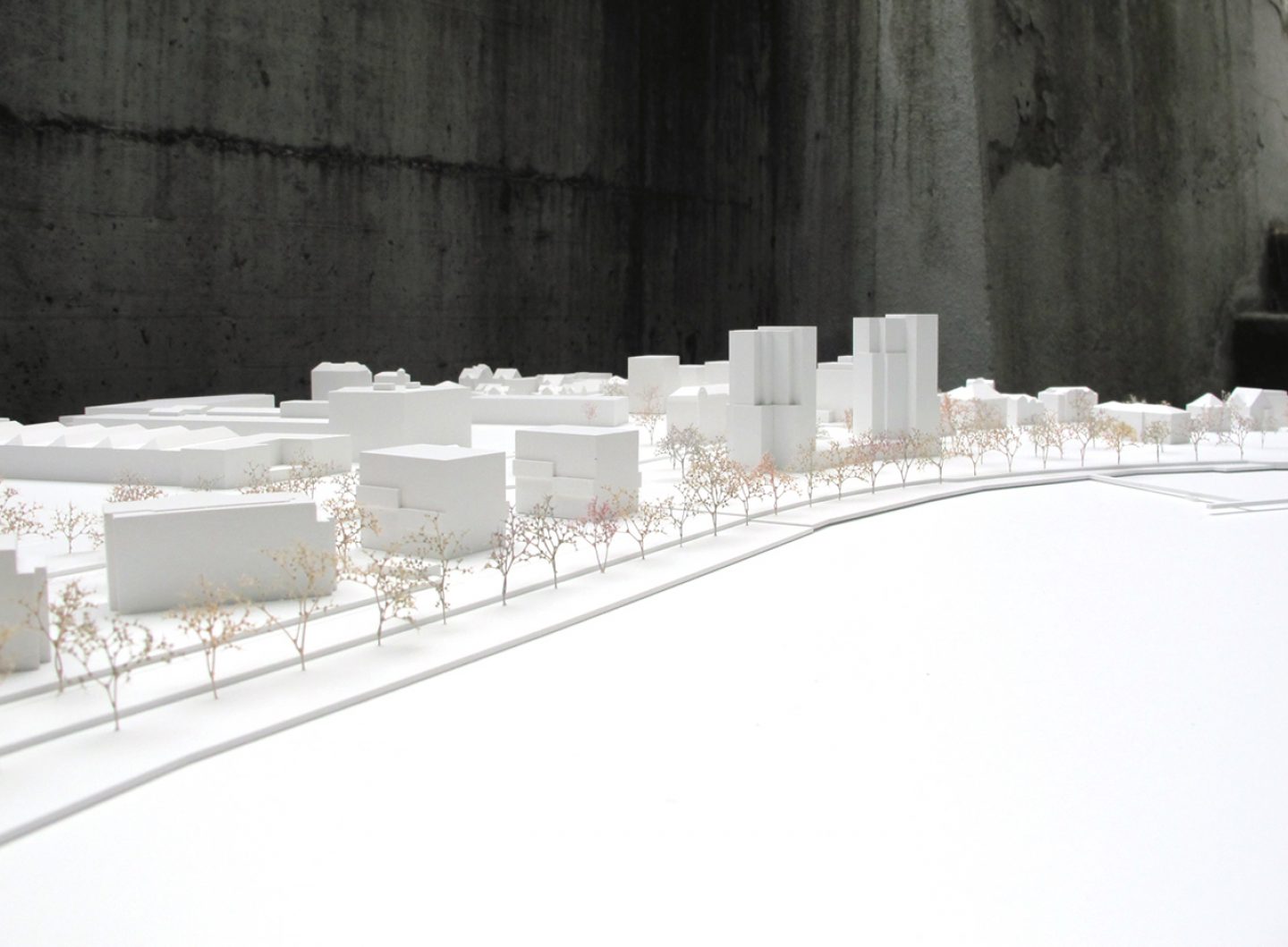

Here’s a selection of projects from MeierHug Architecs:

01: Freibad Jona, 02: Züri WC Stadthausquai, 03: Riva Metropol Arbon, 04: Sonnenhof Wil, 05: Schulanlage Rikon.

Images © MeierHug Architekten

In collaboration with Zürich Tourismus

All images © Clemens Poloczek. Interview by Yasmin Yazdani, translation by Anna Dorothea Ker.