Alec Soth’s Tender View On American Realities

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Dubbed “the greatest living photographer of America’s social and geographical landscape,” Alec Soth has been turning his lens to contemporary American realities for decades. Tender, intimate and often surprising, his photographs – which span portraiture, landscapes and still life to transcend the boundaries of traditional documentary-style photography – are arresting and engulfing in equal measure.

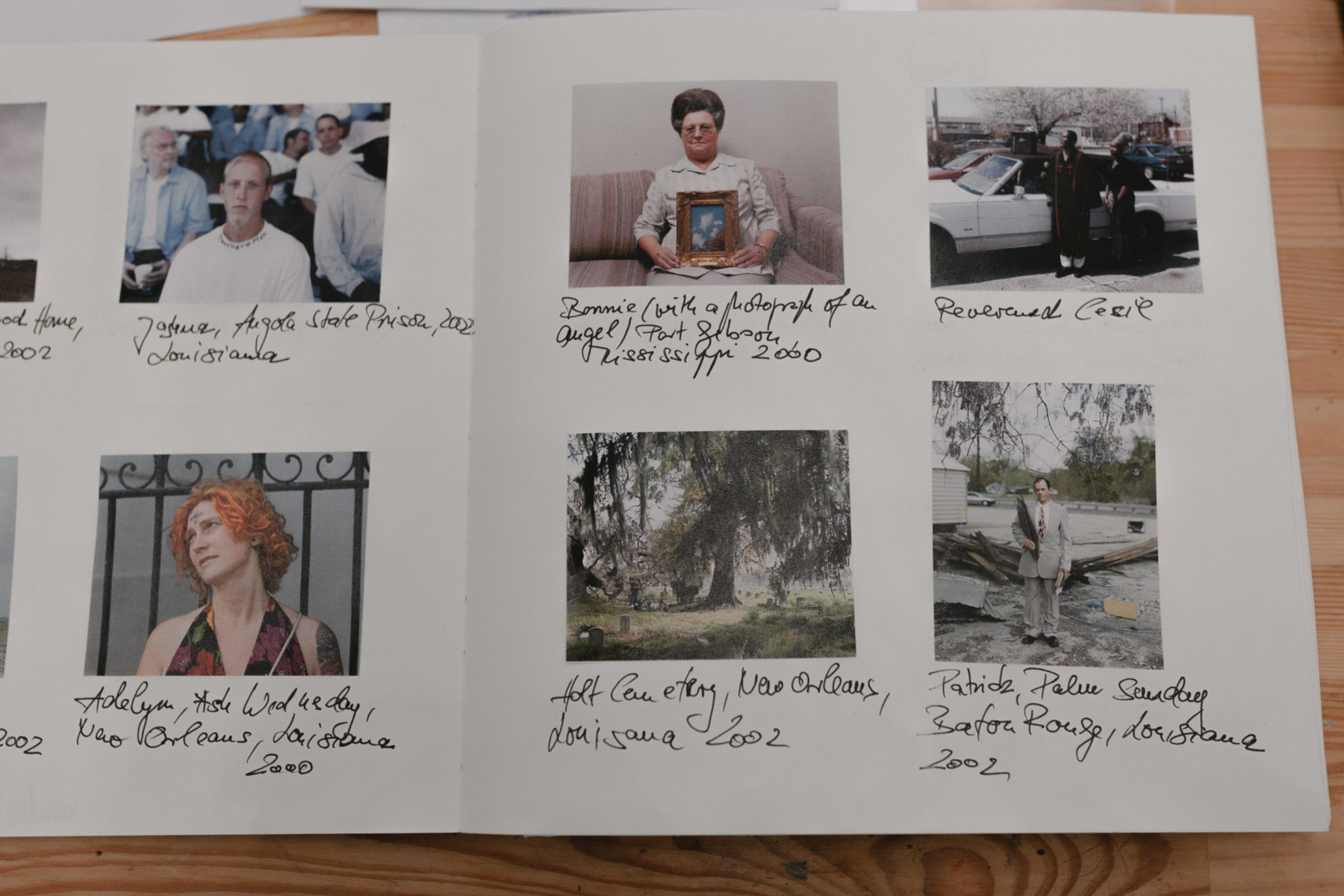

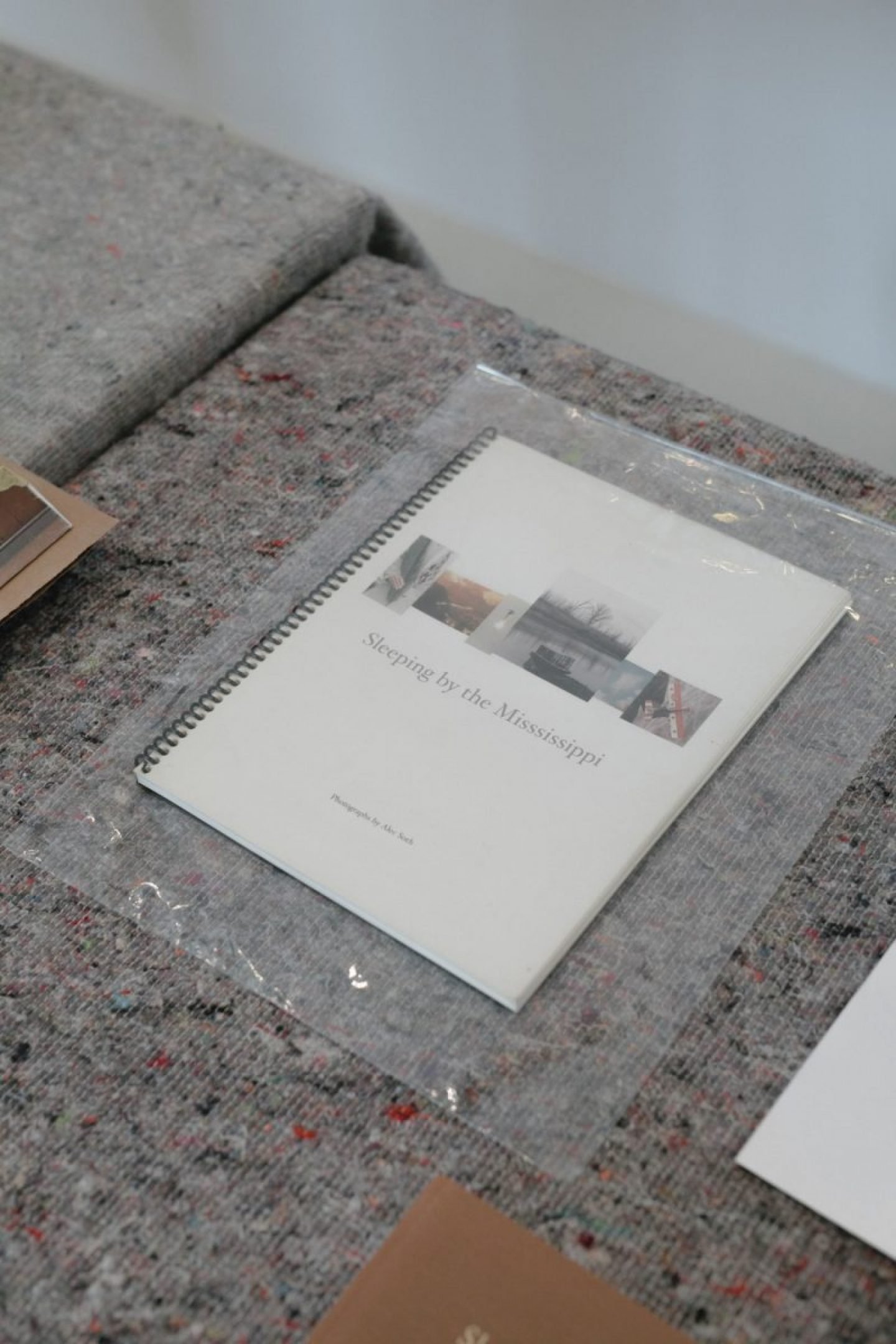

From today (8 September 2017) until 7 January 2018, four of Soth’s most renowned series are on view at the House of Photography at Hamburg’s Deichtorhallen. Entitled “Gathered Leaves,” the travelling exhibition – curated by Kate Bush, Director of London’s Media Space – encompasses “Sleeping by the Mississippi” (2004), “Niagara” (2006), “Broken Manual” (2010), and “Songbook” (2014). Developed in collaboration with Magnum Photos, the exhibitions will be shown together with German photographer Peter Bialobrzeski’s “Die Zweite Heimat”, a survey of the idiosyncrasies of daily life in Germany. Ahead of the opening, we paid a visit to both Ingo Taubhorn, Curator at the House of Photography during the exhibition build and Soth in his Minnesota home and studio.

Interview with Ingo Taubhorn

Our journey begins in Hamburg, at the House of Photography, Deichtorhallen during the exhibition build. Amongst white-gloved gallery assistants carefully hanging large-format photographs in the spacious exhibition hall, we sat down with curator Ingo Taubhorn for an overview of the background to — and walk through — Soth’s survey show. After sharing his own professional pathway into curation, Taubhorn filled us in on how Soth’s work moves him, what we can expect from this show of grand proportions, and the qualities museums offer that Instagram will never replace.

Can you fill us in on your career as a curator so far, and the professional journey that led you to your role at Deichtorhallen’s House of Photography?

I studied film and photography in Dortmund in the 1980s, and was always very interested in the medium of photography, especially from an artistic perspective. At the same time, I was very open to other approaches to photography, and never really made a clear distinction between the commercial and the artistic. And then of course there’s the fact that photography touches many subjects. My approach to photography has always been two-fold: from both an artistic and a theoretical perspective. I applied these professionally for many years as a freelancer, as well as taking photos and organizing exhibitions. From very early on I took a great interest in the history of photography, and not only studied the bodies of work of historically significant photographers but also presented catalogues I made to feature them in exhibitions. I started working with the P.P.S. Galerie F. C. Gundlach in Hamburg, which was one of the first galleries in Germany that was also a photo agency, and which is also connected to the [House of Photography, Deichtorhallen] today. F. C. Gundlach, the great fashion photographer of the ’50s and ’60s: Photographer, collector, gallerist, business man, teacher. He started collecting photography very early on, and also ran ‘P.P.S’: a service for professional photographers. He started a gallery on the fifth floor of the so-called “creative bunker”, where he showcased the works of international photographers, and furthered his collection.

I worked with F. C. Gundlach to do a retrospective of a photographer from the 1920s, and together with colleagues at the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK, the New Society for Visual Arts) in Berlin Oranienstraße — I developed a series, “Unterbrochen Karrieren”, which ran from 1997 to 2002 and was shown in seven exhibitions. At one point I received a call from Gundlach — after it was established that there should be a House for Photography here in Hamburg — in which we’re sitting right now. He suggested I pull together a professional team and a program. That wasn’t too dissimilar to my work at the Galerie F. C. Gundlach. I organised workshops and artist talks. So what at first looked like a limited-term job eventually developed into a particular focus, and in 2006 I was offered the position of Curator-in-Chief of the House. I never foresaw that I would once lead a museum. But the challenges and opportunities that this institution and this role offer are so unique — not only in Germany but worldwide, I’d say — that I simply couldn’t turn it down.

As someone who inhabits the role of both artist and curator, how do you regard the relationship between the two?

I’m always the artist’s assistant. I’m at their service to realise the idea they have in their mind. I’m the agent between the artist and the public. In terms of ideas, information, experiences, rooms — all these elements need to be addressed to allow the visual concept to be conveyed. How a dialogue or a confrontation is built between artist and viewer, that’s the responsibility of the exhibition maker. And the fact that the artists I work with also know me as an artist helps, I think — we work on a similar level. It’s not like I’m just the art- or photo historian who imposes my academic ideals on the artist work and says it needs to be presented in a certain way.

The exhibition has been traveling — from Media Space at he Science Museum in London and London’s National Media Museum to The Finnish Museum of Photography in Helsinki and the Photo Museum in Antwerp. How did it come to be at the Deichtorhallen House of Photography?

So as this is a traveling exhibition that was curated by Kate Bush, Curator of Media Space at the National Science Museum in London, it was offered to me two years ago, and I’ve been following the exhibition tour since. I actually wanted to have it in 2007-2009, when Alec Soth was also exhibiting at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, because I find him one of the most important and influential contemporary documentary photographers, who goes beyond the framework of the style in terms of his themes and aesthetic language. I mean, it’s not a totally new way of photographing — he draws heavily upon the greats of the New Colour movement of the 1970s, like Joel Sternfeld, or Stephen Shore. Yet the way in which he approaches themes offers a new, unique take on our reality. He allows us to bask in them, to lose ourselves in them for hours, both in terms of what we see in them and also what we project onto them.

Although I didn’t work personally with Alec, given the nature of the show, what I tried to do was to create a dialogue between the four “groups” of work within the museum walls. I didn’t take the approach that an art historian might have — that’s to say, to set up the exhibition chronologically — so starting with “Sleeping by the Mississippi”, then “Niagara”, then “Broken Manual” and then at the end “Song Book“. What I’ve done differently is to create an entrance space in which works from both the oldest and the youngest exhibitions come together so the visitor can get an impression of how Alec’s work — and his motifs — have developed and changed over the last 10 years.

Alec is very relaxed when it comes to his images. He trusts in them so much that he allowed me to determine the position of each photo in relation to another, even within each series. I closely followed the show as it traveled around Europe, from London to Antwerp — the curator of each institution chose to show them differently. Here, we give the photos a lot of space — sometimes just one per wall. And that’s a tribute to their power — there’s so much in them that they take my breath away every time I look at them.

Can you walk us through the flow of the exhibition and briefly describe the journey you hope to take the viewer on?

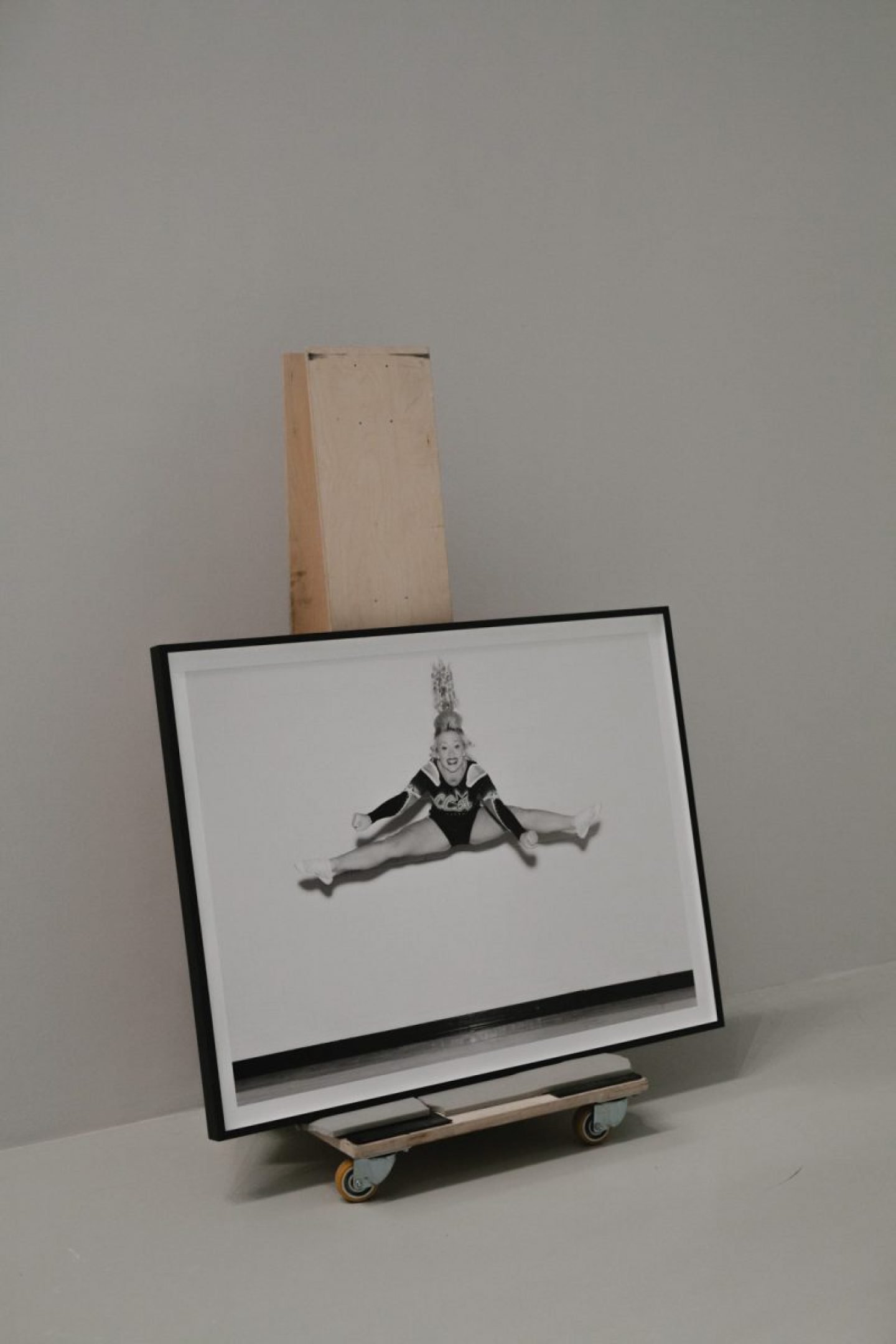

The House of Photography doesn’t function according the the classic round-trip principle, where you wander around a cube from 1 to 4, but instead there’s a reception area — which invites the visitor to find their own way around the exhibition. Say the visitor starts in the large room — they will be confronted with the latest series, “Songbook” — large format black and white works, which reflects the origins of his career, as a pseudo reporter in his homeland, travelling through seven states in the US, where he documented local encounters and published them in fictional newspapers together with the reporter he was travelling with. After this series, we see the differently-sized, vibrant color photos of “Sleeping by the Mississippi”, with which he became internationally renowned. So we can ask ourselves what happened in the 10 years between these two series. Then the viewer can decide to go either left or right. There’s a room with 10 pictures from “Niagara” — which were published in a book themed around love. The Niagara Falls is a place associated with both spectacular acts of suicide and exhilarating honeymoon trips. He kept coming back to the place to take photos of people he met in hotels there, goodbye letters or suicide notes that he found. People who found refuge in a sense of hope, but were also harshly disappointed. People posed for him in an unusual way — say, naked in a hotel room — so opened up to him fully. He juxtaposes these works with almost picture-perfect postcard scenes, and gives us the possibility to project our own feelings onto them. [Curator] Kate Bush only selected 10 of the 37 photos in the series for the exhibitions. So only around one third of the total body of work. But then we see that these 10 photos summarize the essence of the work.

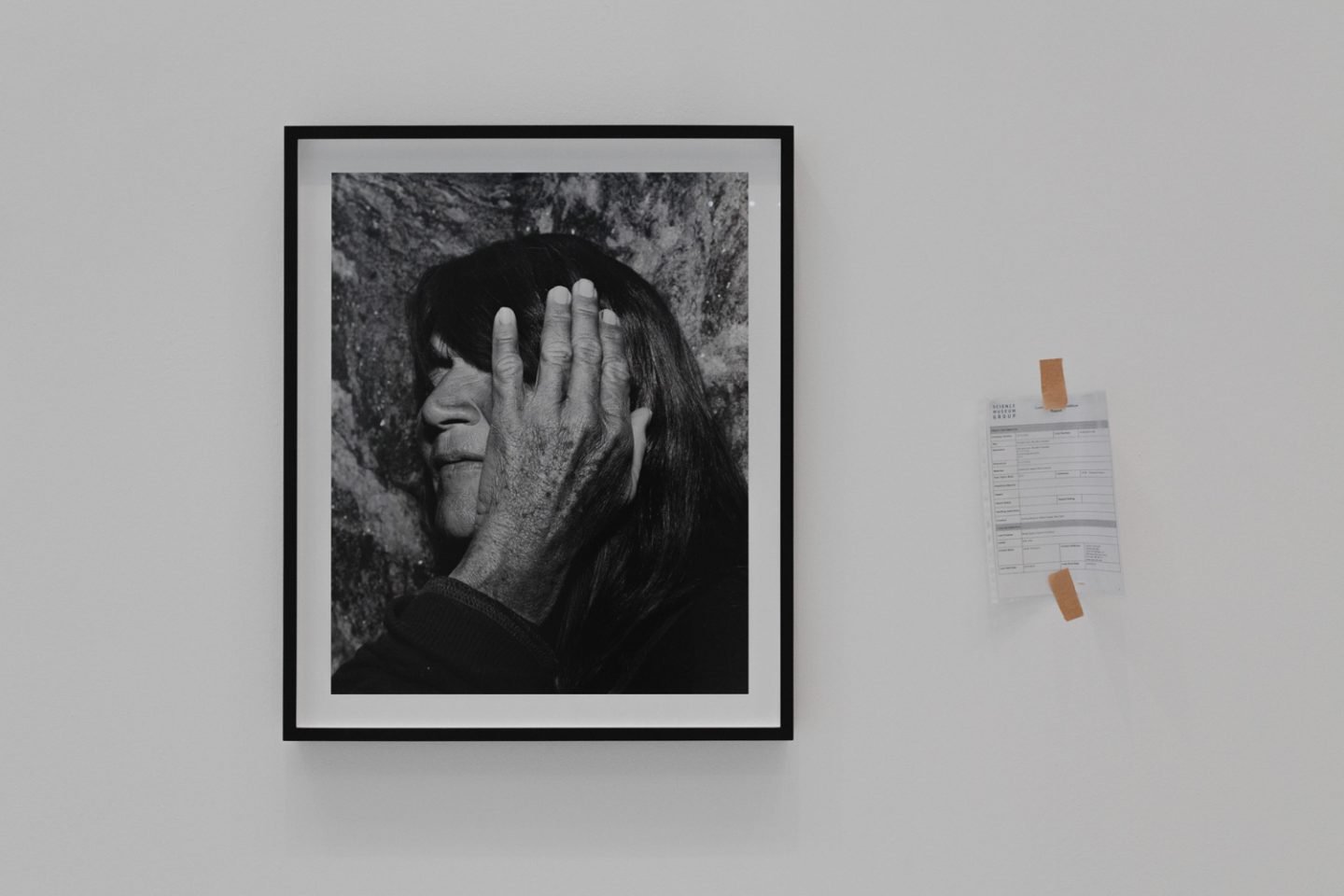

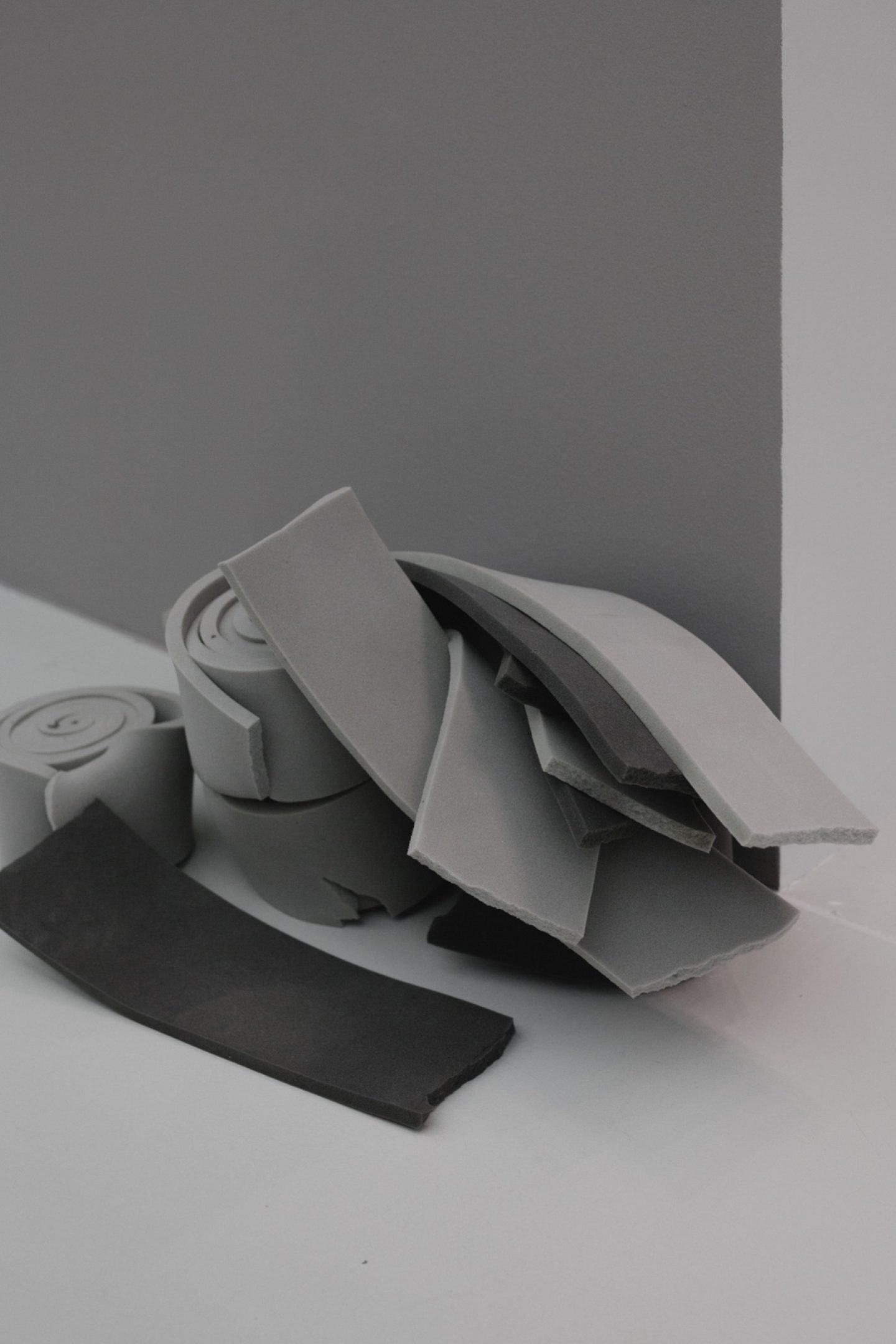

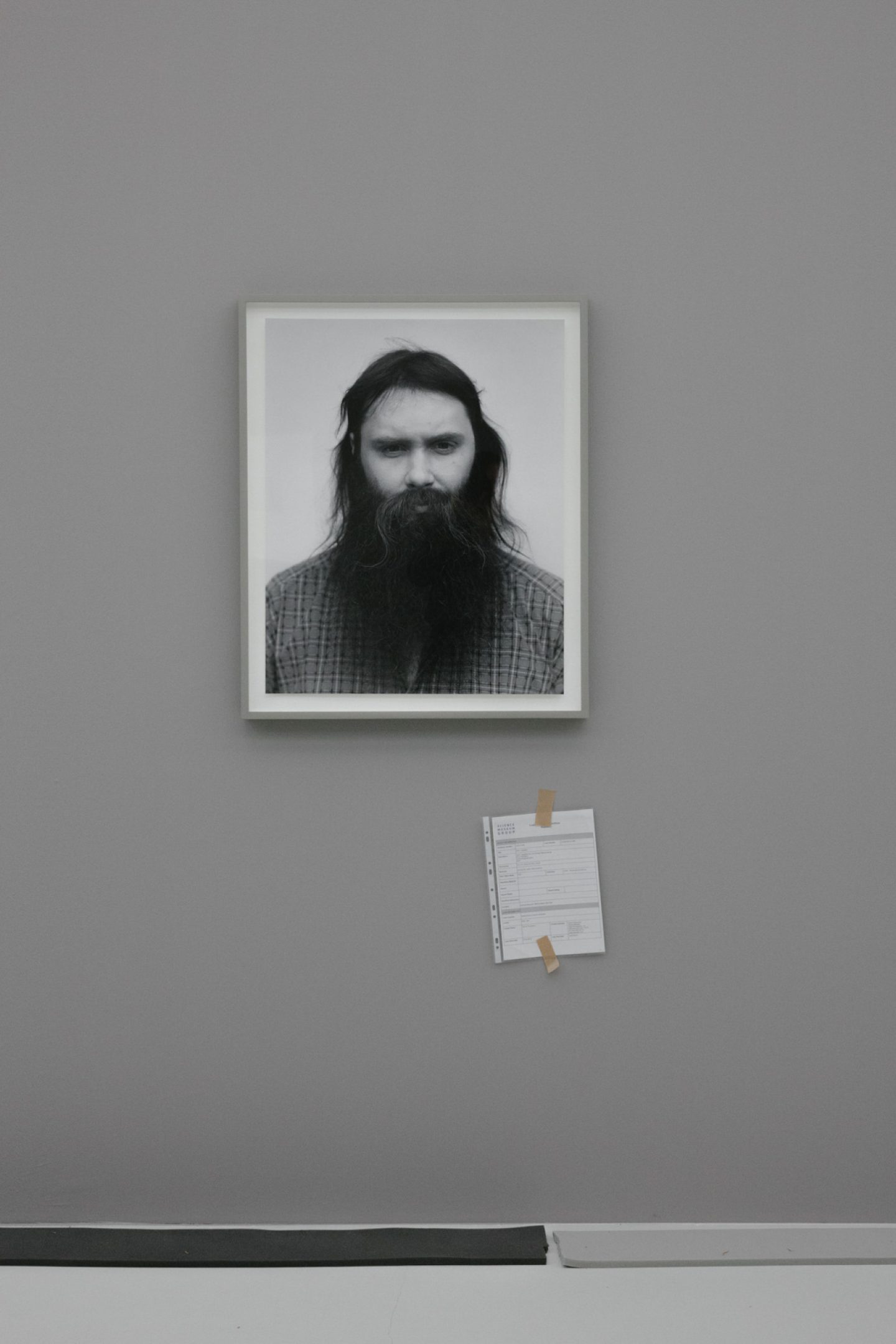

In the cabinet gallery, we have the project “Broken Manual”, which came after Niagara, and was inspired by research he did, addressing the question: What is our place in society? And can we function as part of society while living a hermetic life, removed from it? He was totally fascinated by this subject, and took an approach which transcended his usual documentary style. He photographed objects in a studio, took close-ups of things that are hard to define, and mixed these shots with these hermits and the places they inhabit. In color, in black and white. He builds a story which goes in various directions, which is accompanied by a documentary film which is screened in its own space. What’s new in the exhibition is the very first series, “Looking for Love”, which was 1996 and came out as a book in 2012, we have this in over 40 prints, being shown in a museum space for the first time ever. “Looking for Love” showcases his visual vocabulary, in which he combines a wide variety of motifs, from still lifes and landscapes to portraits. I think this series perfectly describes his love for the medium of photography. And we’re showing this in dialogue with the photographer Peter Bialobrezeski, another documentary photographer who looks at German realities. So there are parallels — both of them draw upon the styles of their role models, like Stephen Shore as I mentioned earlier, both of them work with reality and construct new realities from the realities they see — the difference being Soth looks at the US and Bialobrezeski captures German states of being.

With the oversaturation of imagery that floods the screens on our fingertips, what’s your personal opinion on the difference between viewing a photograph — or a collection of photographs — online and in a gallery space in real life?

I think we can’t escape the fact that we live in a time in which the term “image flood” seems outdated. This term was already coined in the 1980s, and right now it’s more about a tsunami. In this very moment, millions of images are being uploaded on the Internet. I don’t want to turn back time, but I think that gallery spaces offer the possibility for a kind of meditation that separates the experience of taking in pictures from the act of scrolling, zapping from one picture to another, of “liking”, of seeing how many of your own photos are liked… we’ve developed a mode of operating on the Internet where we consider it no issue to forget one picture after only seconds we see it, because we’re already on to the next one. Exhibition spaces, on the other hand, give images room to breathe. And that’s perhaps a little how Alec Soth himself works — Songbook was taken digitally, but the other series were taken with an 8×10 camera. So that ensures not only high quality, but it’s also a meditative process for the photographer. One photo, one setting, wait until something manifests, then develop. And in a way, I think that’s also the purpose of a gallery, a museum. You can spend half an hour in front of an image. And you use your own movements as a zoom. Step back, come closer — to understand the context of an image within a room, or then to lose yourself in a detail. The experience involves all of the senses, the whole body — and maybe also interactions with others. It’s a little like going through a city and not listening to music on your own, but to share a song together with someone. And to perceive sensations that we all share as humans in reaction to something. And that’s not something you can achieve when looking at a tablet or a smart phone. And for that exact reason, I’m totally relaxed about the continuing relevance of exhibition halls. It all has to exist, all serve a purpose — but I’m convinced that the role of museums and galleries will not become obsolete.

Interview with Alec Soth

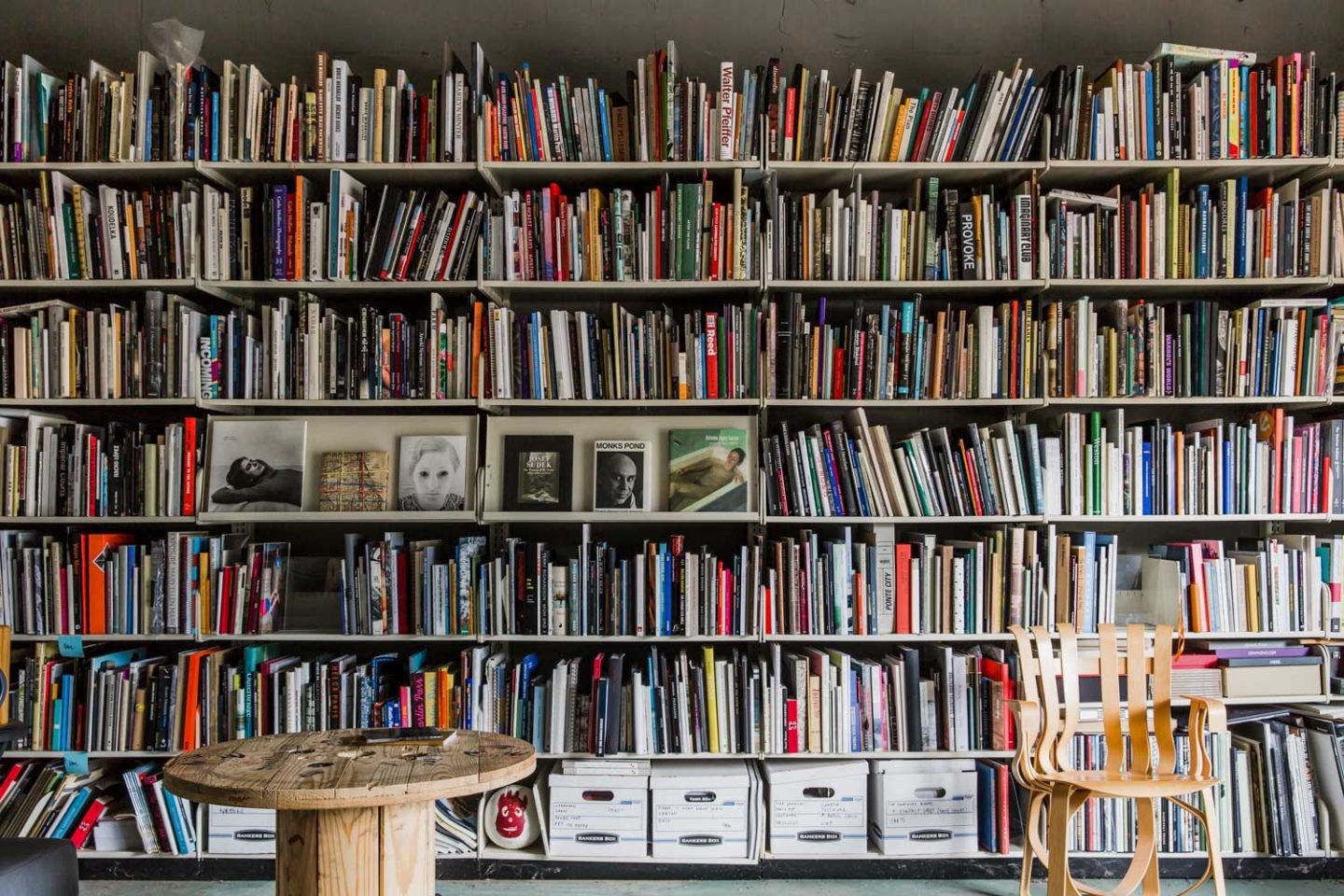

Having experienced the face value exhibition set up, the second part of our interview takes us behind-the-scenes to Alec Soth’s home and studio in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where we had a frank and fascinating conversation with the photographer himself. Humble, warm and reflective, Soth shared with us the motivations behind his work, how he learnt the art of approaching strangers, and his feelings about the current US political climate.

When did you first pick up a camera, and how did you go about turning the craft of photography into your career?

When I first picked up a camera in an art sense was in high school. I had this amazing art teacher who totally changed my life. The first thing he did was to take a map board and we walked around and looked at the world. That made a big impression on me. Then we did a little photography segment, and that did nothing me. [Laughs]. I wasn’t particularly excited by photography. But the idea of that map board made an impression. I was really interested in the idea of making things at that time. So painting and sculptures, stuff like that — till college. And then in college, I was doing sculptures outdoors, which kind of led me back to photography, in a way. It’s like the medium itself was not it. It was more the way it got me moving through the world. It wasn’t about people at all, at first. It was the opposite. It was more like, “here’s this creative thing I can do, moving out in the world, by myself, but not have to talk to anybody. Because I was very shy, and it just wasn’t about that to me. That was much later. I fell in love with photography, with taking pictures, and then I started falling in love with the history of photography, and artists that I love, and I told myself, “I really need to learn how to photograph people.” But it wasn’t fun at first. It was like torture.

Were you learning the technical elements of photography at school?

None of that in school — I was too scared to do it [laughs]. But after I left school, I thought, well I have to learn how to do this. So I started with a medium format camera. Then I got a 4 x 5 with Polaroid — that way I could give people a picture and keep the negative for myself. Because there was so much guilt built up in photographing people, and the Polaroid helped with that. When I was taking those portraits, I was just out of school I knew I was just teaching myself — not doing a serious project but just learning this technique of approaching people. And then I would get a certain kind of thrill from doing it. But it’s funny that I have this reputation that photographing strangers is part of my persona — it’s neither natural, nor something I loved early enough [laughs].

You’ve said the most beautiful thing to you is vulnerability, and I think your ability to capture is one of the elements that make your photographs so evocative. What role does this characteristic play in determining when you click the shutter?

That’s such a hard question to answer. It’s a funny time for me right now, as for the last year I haven’t been making portraits and I’m just starting again, re-learning how to do this. So oddly enough, I’m having this big survey show, but I feel like I’m coming to it all over again, and realising how mysterious this activity is. Because you’re photographing the surface of another human being. So there’s this brain, and then all this activity going on in their bodies that we can’t see. So we’re looking at this exterior, but we have such an ability to read expressions. It’s so nuanced — quite remarkable. But even that only hints at what’s going on in the interior. So it’s not about time. I could spend five minutes with someone, or five hours, or five days — and I might get the same result, and I don’t know, it’s the indefinable quality of it…if I knew the answer, that would be so great [laughs]. My job would be so easy. It’s just a felt thing. It’s like, “why does a certain song give us a certain feeling?” You can’t describe it as a certain mathematical formulation or chord progression, it’s a feeling. And it’s the same for portraiture, it comes down to this feeling.

I’m interested to know whether over time, having gone from being quite shy to having had a lot of experience photographing portraits, how your taken on approaching people has changed?

It has changed over time. Because I was so shy at the beginning, I think that helped me. It was out of my control, and I was dealing with my own vulnerability, because I was quite nervous. People could read that on me. And it sort of enabled them to be more open in a way. But that’s not the case anymore. I tend to approach with more confidence. So that changes the dynamic. I try to be as honest as I can about the situation. I’m honest about what I’m doing and why I’m trying to do it, even if I know it won’t make sense to the other person — if they don’t have the context to understand what I’m talking about. But I feel like if I’m really honest, that honesty comes through, and it enables the possibility that they’ll be honest in spirit with me.

How do you see the interplay between the role of a photographer and the role of a documentarian? What are the most intriguing and frustrating elements of that duality?

When you say “documentarian”, I can feel myself tense up [laughs]. I’m so uncomfortable playing the role of the journalist. I’m aware that there are so many real, committed journalists in the world, and I don’t feel I’m one of them. Documentarian is a looser term, but I still have an awareness of my own internal motivations that are really the driving engine behind everything, for better or for worse. I realise I work in this quasi-documentary way, but it’s more documentary-style. So it’s not true documentary photography, but it looks like it. I’m more comfortable inhabiting that place.

Can you expand on what you mean by your internal motivations?

I mean, the larger body of work which is represented in the show, usually comes from whatever I’m grappling with at a given time. So whether it’s “Broken Manual” —my own desire for seclusion and retreat, or “Songbook”, the inverse of that, or the desire to reconnect socially — it’s coming from things I’m thinking about in my own life. So I’m projecting that on to the external world, and I guess there are certain ethical implications in that.

How did you first develop your relationship with Magnum, and what does being a Magnum photographer mean to you at this stage in your career?

So as I said I came to photography from this art side of things, and Magnum to me was like war photographers — I didn’t think much about it. And then once I had a career at a certain point, I had to figure out how to sustain myself. And an art career didn’t seem sustainable, so I started doing magazine work, and learned a lot more about Magnum, and realised that it always had this mixture of the arts side and the journalism side. Even [Henri] Cartier-Bresson himself was formerly a surrealist — so it had this sort of built-in tension within it. So that was attractive to me. Fundamentally, it helped globalize me. It helped me meet a lot of photographers, exposed me to different ways of working. The really important thing about Magnum is that it’s a co-operative. It’s owned by the photographers. Which makes it like a family. A super complicated one, like all families are. My relationship to it exists more on that level than the idea of a roving photojournalist. Because it’s always had these outliers, these people who work in different ways.

You’ve been named “the greatest living photographer of America’s social and geographical landscape” (by The Telegraph). That’s an honorable title — but one that bears heavy responsibility. What are the main imperatives for you in documenting life in the current US political climate?

It’s been huge. I mean, this show started before this disaster, and so this conversation is inevitable [laughs]. The current political climate has had a profound impact on me. Because these four projects are all very much made in America, and mostly in middle America — “Trump land”, and all of that — and historically I’ve been a big defender of middle America. That it’s richer and more complicated and weirder and more nuanced and more varied than people give it credit for. Because it’s termed “fly-over country”. Or photographers drive over, but they take the freeway. What I’ve always said is, “just get off the freeway and everything is more interesting.” It’s not Starbucks and McDonalds, it’s more nuanced. So these things I’ve said over and over again, hundreds of times. But I haven’t been traveling since the election, and I’ve really come to question myself. Was I wrong? In part, because I’m in a media-saturated headspace more than talking to other human beings. But I am super jaded. And horrified, and embarrassed, and really confused. I mean, I’m truly baffled by the situation. It’s challenging.

Which country, culture or society that you would love to photograph next, and why?

I was doing a lot of work in Japan for a period of time — I made four trips to Japan, and I’ve sort of put that on the back burner for some time now. I’m fascinated by the ways in which I can’t connect with it — my own distance from it. It’s impenetrable, to some extent. I mean, the northern culture which I come from is a more distant culture. So less emotionally open, and I respond to cultures that have that similar quality, I guess.

Photos of the House of Photography at Deichtorhallen by Ana Santl. Photos of Alec Soth’s Studio by Ashley Sullivan. Interviews Anna Dorothea Ker.

Exhibition: “Gathered Leaves” by Alec Soth

Location: Deichtorhallen – House of Photography

City: Hamburg, Germany

Date: 8 September 2017 − 7 January 2018