At Second Glance: Guillermo Santomà

- Name

- Guillermo Santomà

- Images

- Silvia Conde

- Words

- Julia Keller

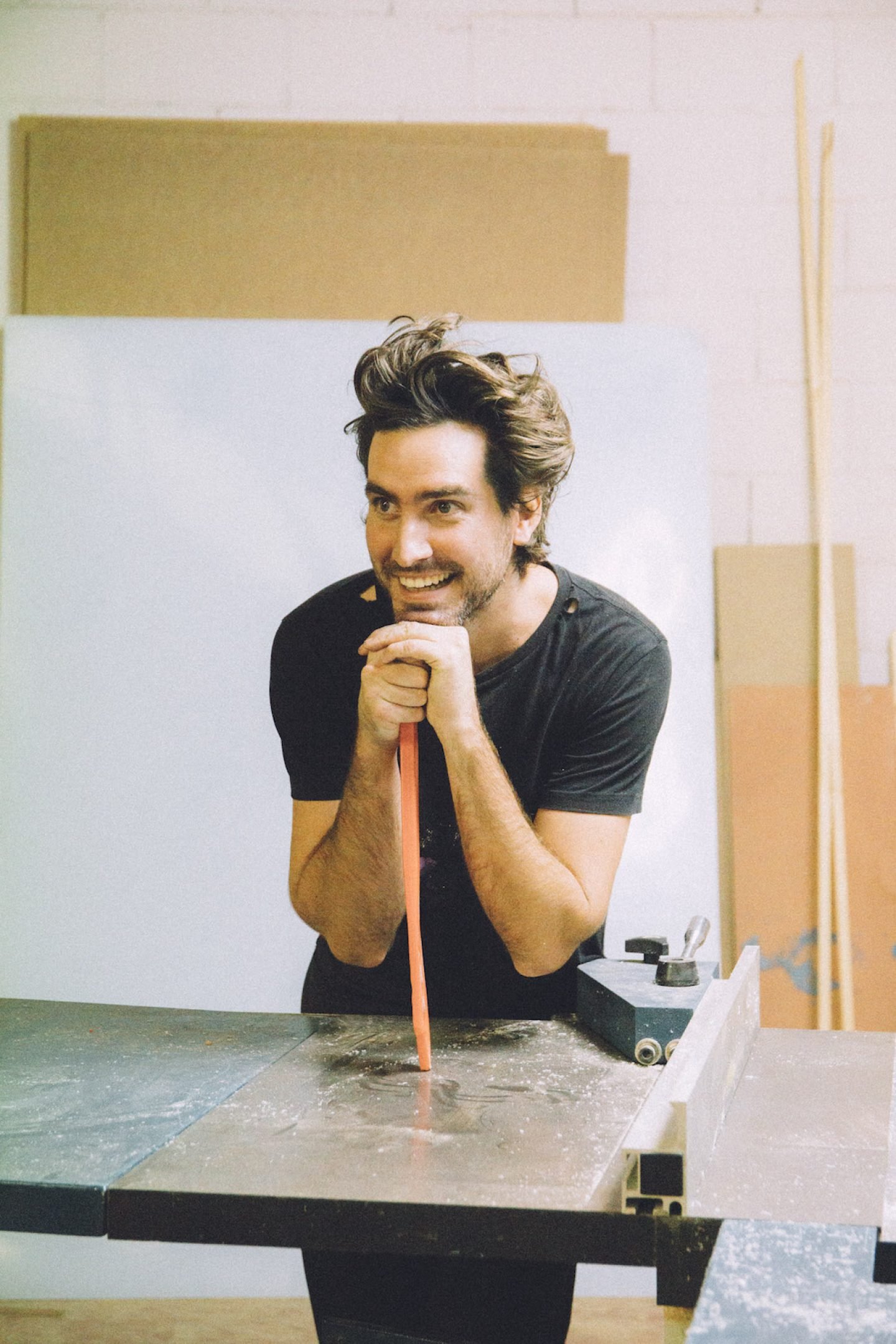

When a makeshift cardboard hut makes it to the cover of one of today’s most ubiquitous interior magazines, there has to be more to it than meets the eye. The designer of this hut is the Barcelona-based architect and designer Guillermo Santomà, and as it turns out, the structure’s urban shelter look wasn’t designed as an eyecatcher but was born out of a need for affordability, paired with a penchant for functional and unassuming materials.

Besides this project being one of Santomà’s briefest — he built the whole thing in less than a week — amongst a large and varied body of work that taps into the territories of interior and furniture design, installation, scenography and exhibition design, its simplicity makes it the perfect starting point from which to understand the architect’s modus operandi.

Here’s the backstory: Santomà was approached by his friend, artist Maria Pratts, who asked for help setting up her new living quarters in a large studio space in the outskirts of Barcelona. One of the premises of the design was that it had to be low-cost, as Pratts had only a thousand euros to spare for her future home. Despite this limitation, or perhaps stimulated by it, Santomà decided to take on the challenge. The brief was to create a space that the artist could retreat into, a refuge of sorts, counterbalancing the large, open warehouse that served as her workshop during the day.

In an attempt to humanize the scale of the space, as Santomà puts it, he built a small, lower structure into one end of the room, aiming to create something that stuck its nose out into the work area. “The structure itself is very simple”, he says, “but complex at the same time. Reaching simplicity is much more work than doing something overloaded. Behind it lies a big effort to geometrize, to break it down to its essence in order to make it easy to build.” The use of cardboard as cladding material was a cheap way to provide isolation, but Santomà also found its humble appearance appealing: “It’s like creating something very architectonic and then stripping its value away from it, in order to achieve something that doesn’t look like it was entirely thought out.” Looking around Santomà’s own warehouse studio, located just ten minutes from Pratts’ place, it becomes clear that using modest materials, and twisting and turning them in order to create something much more complex and refined, is a recurring feature in his practice.

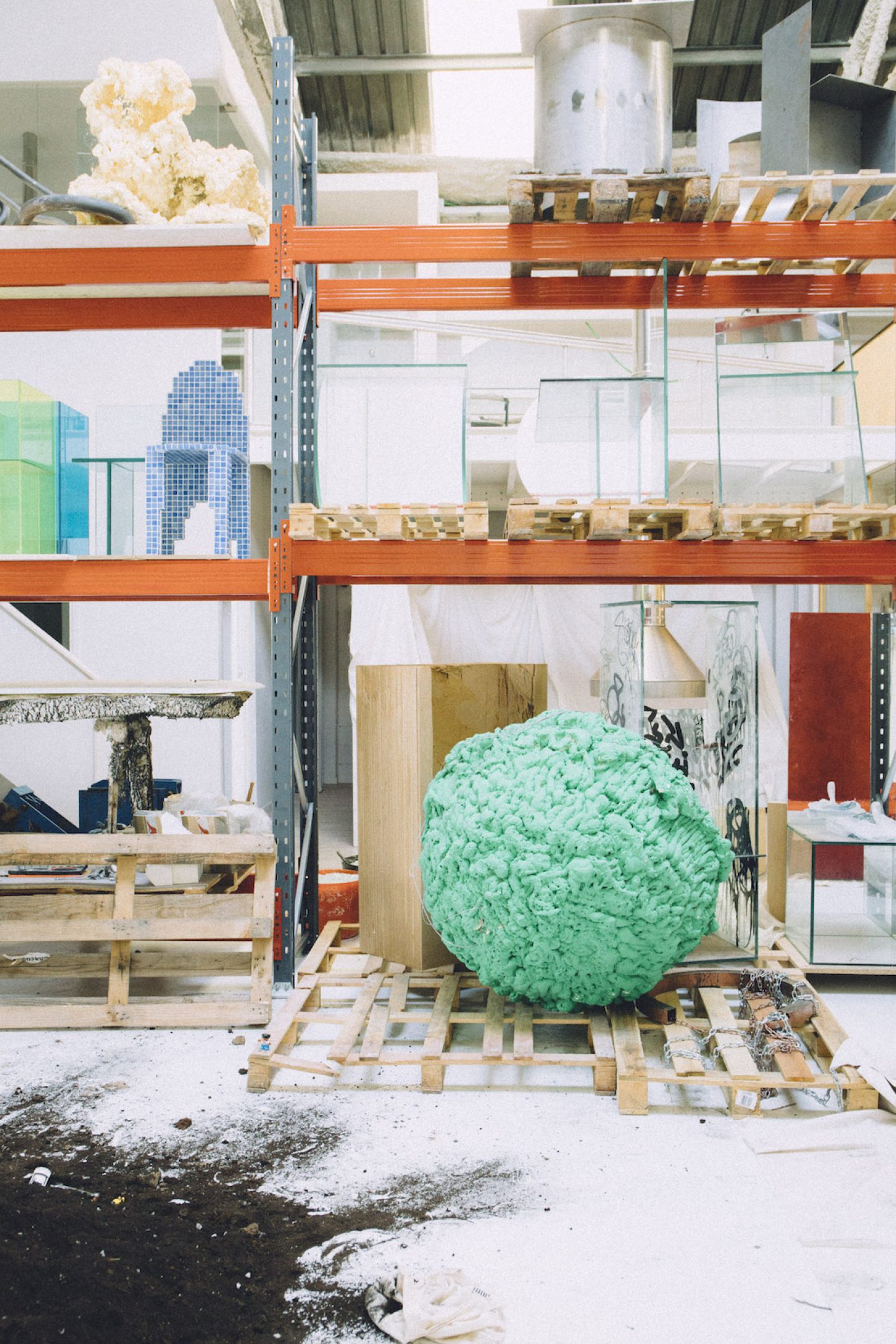

A large industrial shelving unit located right next to the entrance of serves as a three-dimensional portfolio of his work, displaying multiple variations on one of Santomà’s favorite forms: the chair. The objects on display have been created either from scratch, using a plethora of unconventional shapes and unexpected materials — amongst them are pool tiles, broken glass, foam, and rocks — or by modifying existing designs. The latter is the case with his redesign of the ‘Monobloc’, “the world’s most common plastic chair”. By melting its backrest and coating it in powder pink, Santomà has taken the chair from completely mundane to something that would blend seamlessly into Sean Baker’s latest movie, The Florida Project.

Despite his fondness for seating, Santomà isn’t one to remain idle. Time, or the lack thereof since he became a father three years ago, is his biggest challenge, and learning to use it effectively is the sine qua non for the success of his projects. Santomà is utterly committed to the work he does, and being unable to disconnect is an unavoidable side effect: “Nowadays I’m hyper-efficient. But the reality is that you don’t think about anything else. So even if you have a strict work schedule, it’s not entirely true to say that you only work until a certain hour.”

Much like using the narrow budget for the cardboard hut project as an opportunity to boost his inventiveness, self-limitation seems to play an important role in Santomà’s work philosophy. As is true for most creative people, “the internet is everything, both as a source of information and inspiration”, but in order to eschew the perils of the internet rabbit hole, he has chosen not to have a computer in his studio. “I can go out for breakfast and write five emails from my phone. If I sat down in front of a computer, I wouldn’t get up in the entire morning. Owning one is a waste of time.” While that decision might not be entirely surprising, the fact that the working tools in Santomà’s workshop are also subject to his self-restriction strategy is all the more so: “I’m basically against machines. Having only three of them forces me to be very creative and establish strange collaborations with my own tools, to use them in a different manner every time.”

“I’m basically against machines. Having only three of them forces me to be very creative and establish strange collaborations."

As I point out the various ways in which he seems to coerce his mind and body into being more effective, Santomà refers to writer Roberto Bolaño as a source of inspiration: “He used to write in the cold, or while listening to heavy metal as an act of self-limitation. The fear of death also served this purpose — he knew that he would eventually succumb to his illness, which made him super productive.”

In order to foster creativity and gather ideas for new projects, Santomà relies on collaboration, which isn’t limited to bouncing ideas off with his clients or studio assistants: “Collaboration is an essential part of any process. In the end, you’re a computer that processes information and takes it wherever it wants. It’s the same if you’re browsing the internet — you’re actually collaborating with it. When you’re reading a book, you’re collaborating with the author; when you watch a movie, you’re collaborating with the director. It’s a constant dialogue.”

During the research for this interview, we stumbled upon a piece where Santomà mentions that one of his favorite books is a compendium of Andy Warhol interviews, “for his capacity to generate mysteries and come up with absurd answers to absurd questions”, he explained. With this in mind, we asked Santomà some of the questions that appear in the book, in exactly the way they were posed to Warhol in various interviews between 1962 and 1987.

Creatively, do you feel in good shape?

Of course, I go to the gym every day!

What was your first work of art?

I remember it very clearly. I was six years old, and I made a clay bust of my grandfather which was like the epitome of a grandfather: he had a cigar in his mouth and wore a beret. Even though my grandfather didn’t smoke, and he never wore a beret, I insisted that it was a portrait of my grandfather. That sculpture is the only object my mother hasn’t let me take with me since I moved out of my childhood home.

Is there anything you would like to do that you haven’t done before?

Well, that’s exactly what I want to do, something I haven’t done yet. It’s what I aim for every time I do something.

If there was a museum dedicated to you, what would it be like?

I hope there will never be a Guillermo Santomà museum, that when I die, we will have outgrown the traditional idea of a museum.

What is your vice?

Everything is a vice. I don’t have a favorite one.

Would you rather be the bad guy or the good guy?

It depends. You sometimes need to be good, and sometimes bad. I don’t mind either. The good ones can seem very bad at times.

Do you go to the beach?

Now that I have a son, yes. But I didn’t before.

Who was the first artist that influenced you?

I don’t know. In the end, you’re not aware of everything. I think I’ve been influenced more by experiences — being in nature, sailing or flying, climbing to the top of a mountain — or relationships, rather than by a particular artist. First, you have images, and then you’re able to construct them, but you always need to have lived or felt them first. It’s the only way to empathize with people. Without the direct experience, you can’t really get influenced by someone. We’re probably all marked by our parents. They are the first people that influence us.

Which was your first professional success?

I don’t think I’ve had it yet. To me, professional success means that you get paid a lot. And that’s the struggle I have with my galleries right now: the fact that they should pay me more. It’s the only way to evolve, to not keep doing the same thing. I’m being represented by two galleries at the moment, Etage Projects, and Side Gallery, for exhibitions and commissions. But I actually don’t do commissions in the sense of “do this again, but smaller, or in a different color”. It’s messed up, but that’s what the clients ask for. At the moment, I’m completely against that.

In the end, galleries have all the bargaining power. You sometimes lose money making an exhibition. But they call you again, and you say yes because it’s the only way to keep doing your work. It’s an unhealthy relationship. The only solution is to keep being yourself. You either sink or swim, there’s no other option. In the end, to spend your life doing things you don’t want to do, you might as well switch careers, start serving coffees or do something else that doesn’t take such a mental and emotional toll on you.

What does Coca-Cola mean to you?

When I feel a bit dizzy I drink a coke. It gives me a sugar high.

Do you watch TV?

Yes, on Sundays. I watch TV and eat pizza in bed. And I drink coke.

Do you believe in magic?

Yes.

What do you usually have for breakfast?

I don’t have breakfast regularly. It depends. You listen to your body, and there are days when you’re just not hungry, and on other days you’d eat an entire chicken. My eating habits are listening to my body rather than eating at designated times. I don’t always need coffee to start the day, I sometimes order tea. Or even a coke. It might seem odd to be having coke for breakfast, I’m disgusted by it myself, but something inside of me tells me that I need it.

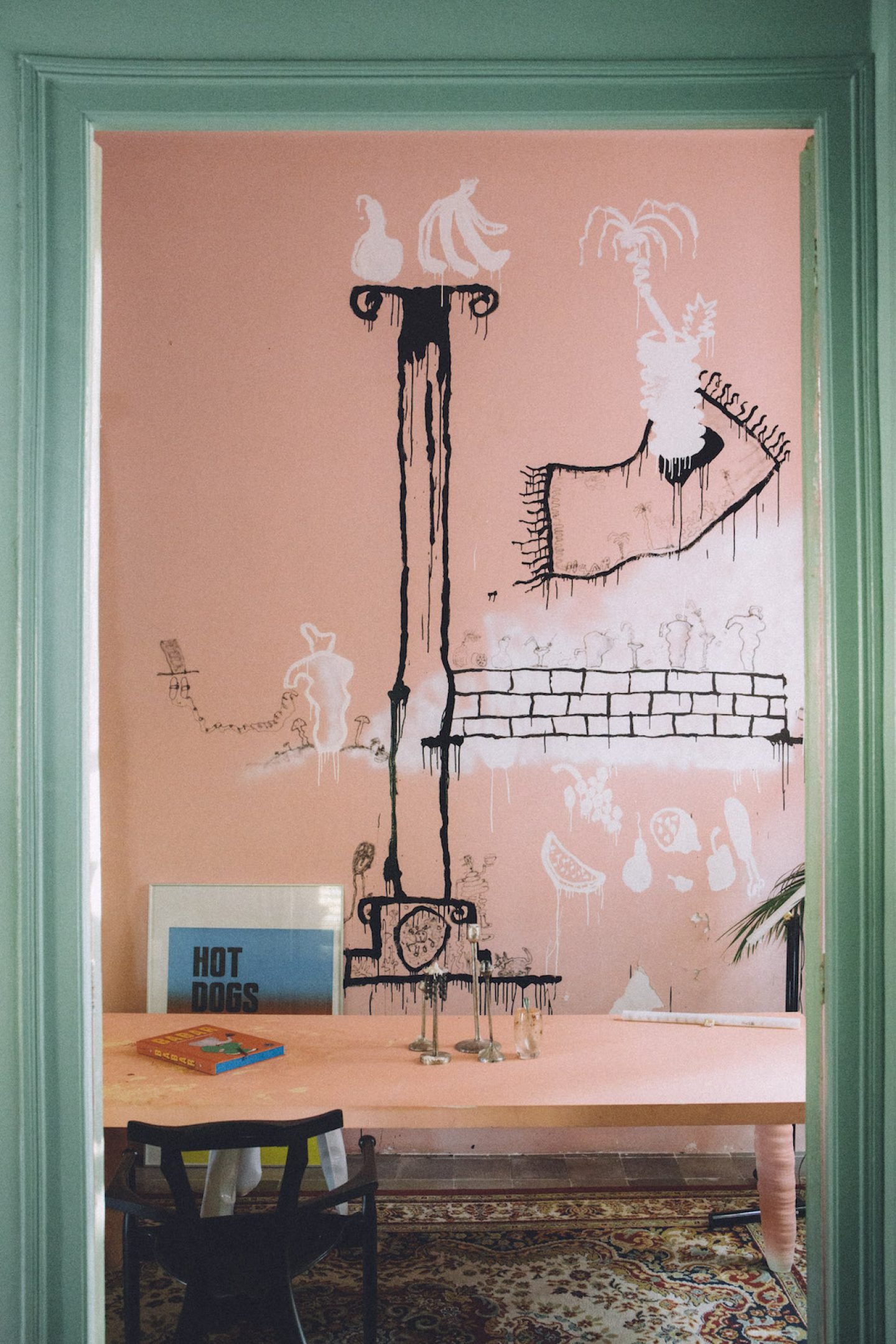

The same thing happens when you work on a project. A hidden voice tells you: you have to paint it yellow. Or: paint it pink! I remember that, when I was renovating my current home, nobody wanted me to paint it pink, everybody was completely appalled at the idea. I have a painter friend who told me I was crazy, that it wouldn’t work chromatically. I ended up looking at a ton of shades of pink before I decided on one, but it had to be pink.

A selection of Guillermo Santomà’s work

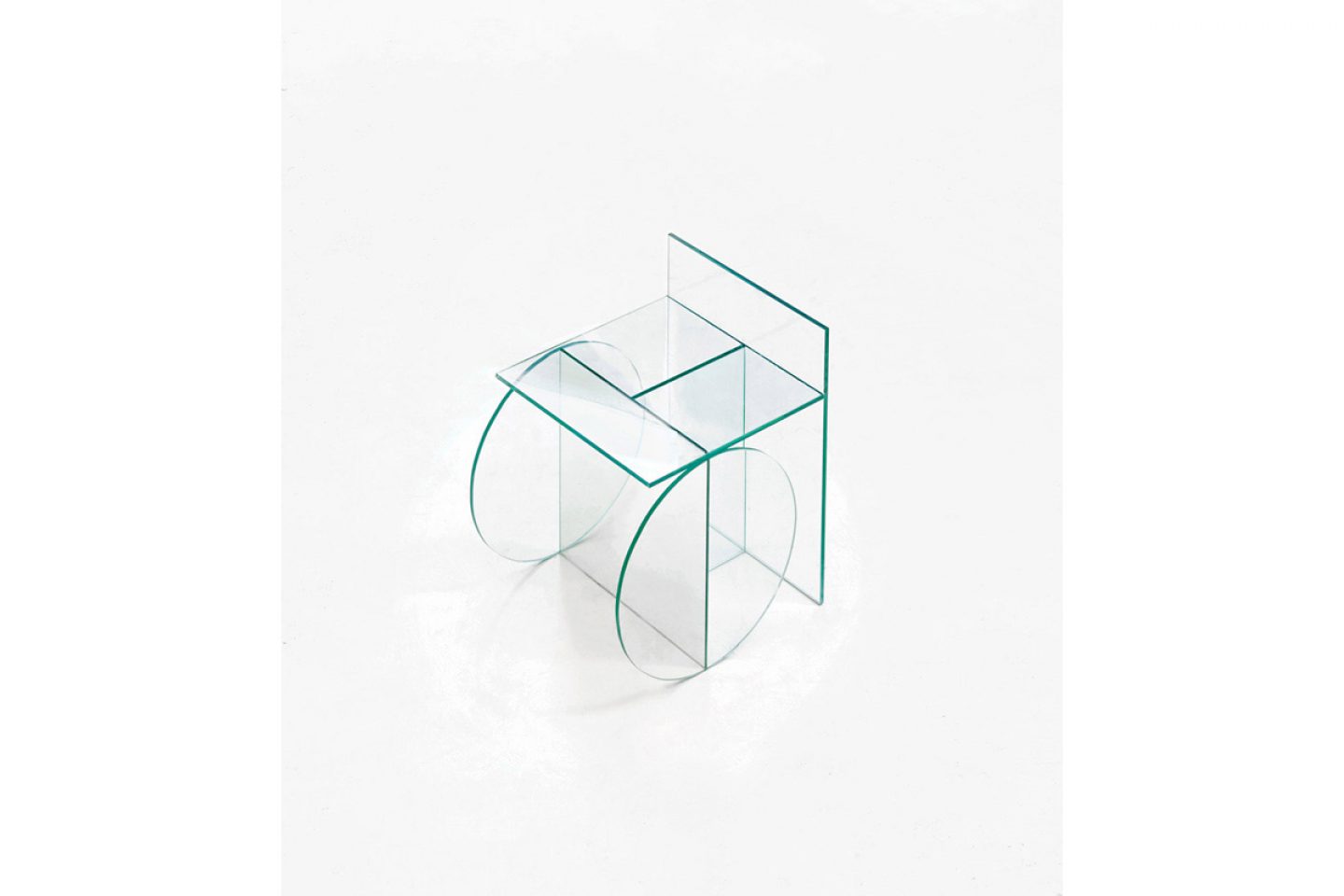

001 ‘Cristobal De Moura’ (in collaboration with Sander Wassink)

002 Glass mirror structures for Dries Van Noten (photo by José Hevia)

003 Cardboard Hut

004 Darial

005 MDF & Wood Swimming Pool (photo by José Hevia)

006 Chandelier (in collaboration with Etage Projects)

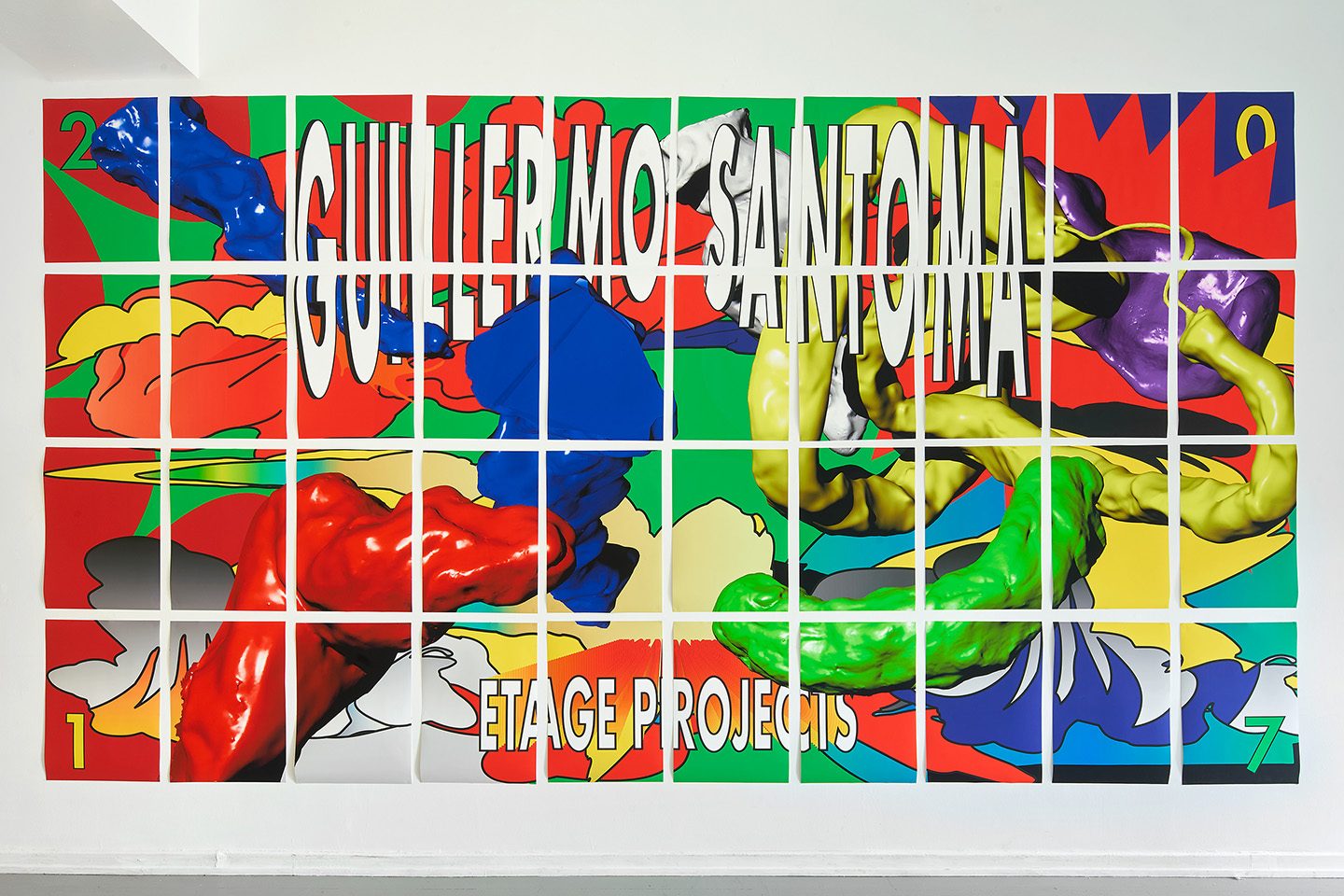

007 Bullet Point Exhibition (in collaboration with Etage Projects)

008 Bullet Point Exhibition (in collaboration with Etage Projects | posters by Raquel Quevedo)

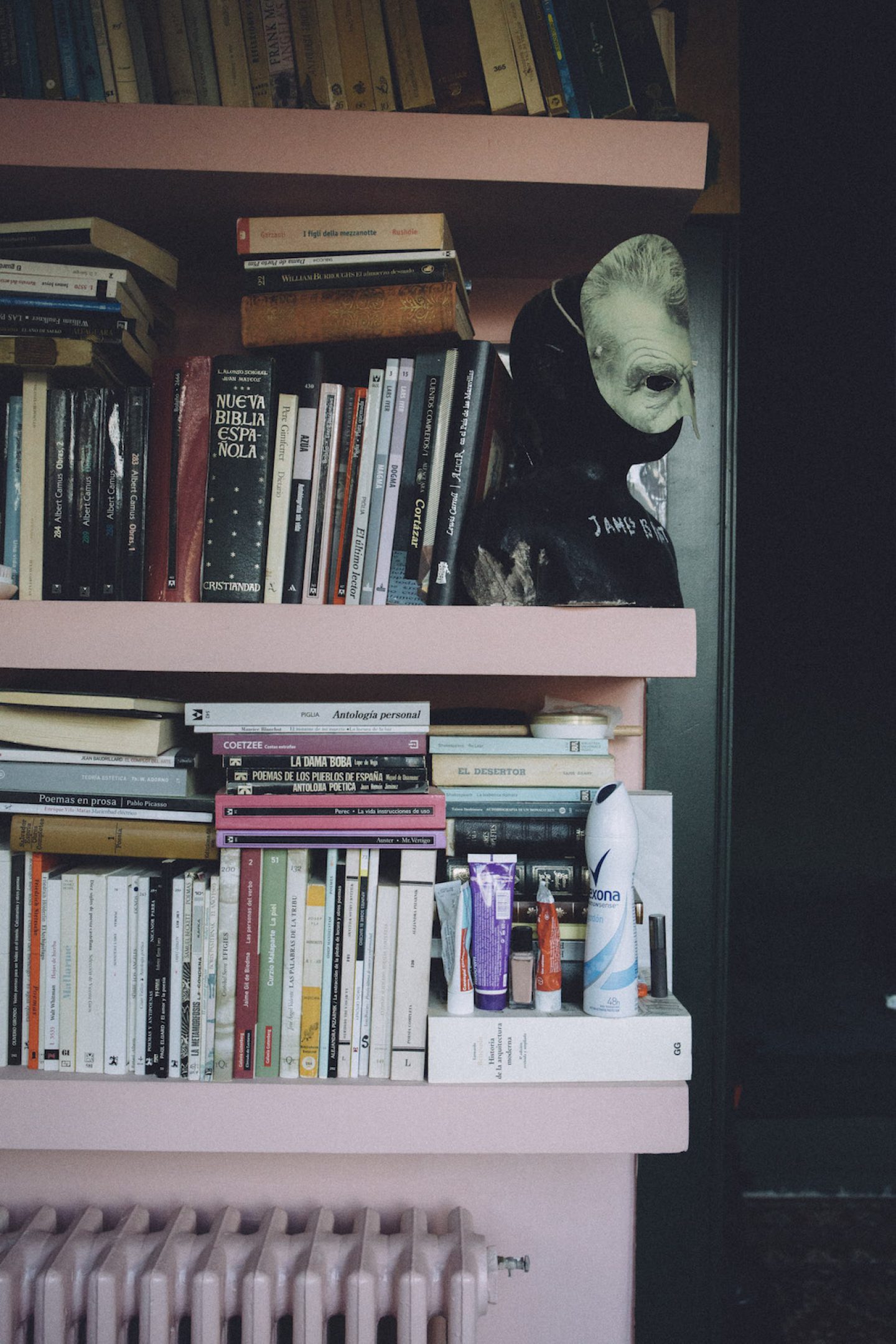

‘Casa Horta’, the name Santomà gave to his pink home in the Barcelona neighborhood of Horta-Guinardó, is the last stop on our interview tour. As one of his most notorious projects, it has been featured in countless interior and lifestyle magazines (including our own), and its utterly photogenic green and pink living room has subsequently colonized Pinterest boards and Instagram posts. But as we walk through the entrance of the pastel green turn-of-the-century building, what we see is something fundamentally different in one crucial regard: this is not a house, but a home.

Contrary to the impression given by the stark, render-like photographs of ‘Casa Horta’ that roam the internet — courtesy of his long-term collaborator Jose Hevia, and which Santomà favors for their similarity to the images created by virtual rendering software — it is in actual fact, a lived-in family home. While the overarching vision that Santomà had for his house in terms of volumes, shapes, and colors is still very much present, a layer of everyday life has been superimposed on the architectural model: crumbling plaster, plants in need of watering, squished couch cushions, childrens toys lingering in the corners.

Of course, the house is still a far cry from average-looking, most of its furniture could be considered a “statement piece”, but they still manage to blend in with their surroundings quite naturally. And Santomà isn’t too precious about them either. In the basement room, the combination of Starck’s ironic garden gnome and Noguchi’s freeform sofa is counterbalanced by the fact that the space is still unfinished and lacking a window, which has prompted a street cat to use the designer sofa as his new night quarters, Santomà explains with a mix of resignation and amusement. He cares, but not too much, and is willing to let things take their natural course.

The whole house is still very much a work-in-progress, and it seems to grow slowly and organically, adapting to its owners’ evolving needs. The garden wasn’t planted until last year, and what was once destined to be a first-floor lounge area is now being used as a bedroom, at least until the bedroom that is currently being built on the second floor has been finished, which then might be replaced by an outdoor bedroom on the upper terrace, something Santomà has always dreamed of.

This constant quest for change and evolution marks both his personal and professional life and in that quest, getting too attached to something can be a hindrance. That might be the reason why Santomà is trying to convince Pratts to burn down her cardboard house and start from scratch, repeating the process on a yearly basis and using different materials each time. Fittingly, ever since an article about his work with the title “To Create Is To Destroy” was published, Santomà has become the “artist who destroys things”, he tells me. While that might be a catchy label, the truth is that “the artist who destroys things in order to keep creating” seems much more fitting.

Text by Julia Keller | Images studio & home by Silvia Conde for iGNANT Production