On Concept-Driven Design With OS ∆ OOS

- Name

- Os & Oos

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

Oskar Peet and Sophie Mensen of OS ∆ OOS studied together at Design Academy Eindhoven, “but we didn’t really see each other at the beginning”, explains Oskar. It wasn’t until Sophie returned from a residency in Estonia that the pair met at a party, and the rest — in both love, and design — you could say, is history.

After working together on a number of projects, they quickly realized that instead of invoicing one another for their work separately, it would make sense to launch a company together — and so OS ∆ OOS was born. The Dutch industrial design duo creates work that is firmly situated on the edge of art and design: rational in form, but conceptual in basis. Speaking to the pair from their studio in Eindhoven, the complementary nature of their relationship in both work and life is evident. They have a rhythmic and relaxed means of communicating, speaking somehow together — though from different mouths. Oskar tells me that Sophie is a creative force, and Oskar, Sophie explains, makes sure their design ideas don’t fall apart. We spoke at length about their working process, concept-driven design and the climate of creativity in Eindhoven (which, despite their initial misgivings, is becoming “more and more difficult to leave”).

How did OS ∆ OOS begin?

Sophie: Well, we didn’t really start off saying “Let’s start Studio OS ∆ OOS”, I think it was two years after our graduation work that a big company asked us individually to be part of a group exhibition with some other old students from the Academy… and we thought, yeah, let’s do this and see if we can really work on a project together! So that’s when we started making the Syzygy light series and that got quickly picked up by the galleries, and there it grew actually. From there it took another two years before we really said, “Ok let’s really start our own business, it’s doing pretty well, and we like to do this”, then we started the studio.

Oskar: And we also had side-jobs up until we started selling more and more of these lights, and that’s when we thought “Hey, we can actually maybe make a living from this”. At that point we realized that we needed to have a name, we needed to have a website, because up until then we were just invoicing each other — we were still two individual businesses.

Do you feel like you have a division between home life and studio life? Or are you very much always working?

S: Perhaps (laughs). I just got my [motorcycle] license three years ago and we do these track days, where you go and do races —and on those days you are in a totally different world. It’s something that’s very helpful. I mean, we also like to go to museums and to see other things, but sometimes you also need to be in a place with a difference, a different world.

O: Somewhere really different from design, you know. You need that contrast because even a museum can feel like work in a way, because it’s aesthetics, its compositions, and shapes and every time you see something it inspires you, and you immediately associate it back to your work, so that’s why the other hobbies are pretty important. For the most part, we are still at until 7 or 8 o’clock at night, and then on Saturdays, we are usually working as well…

S: No…

O: Well, we are trying our best to divide it!

You work across a very broad spectrum of design: how do you approach these different elements of design?

O: We really like to work with concepts — we have a feeling of what we want to work with. Since the beginning, we’ve sort of initiated our own projects, all we needed was an exhibition or a deadline and then we would go off and make something and then, we’d sort of put it into the world and then people would react. We also try to work with modern or new materials instead of working with materials that it was possible to work with many hundreds of years ago, or techniques.

I think that kind of flexibility is required of designers today

S: I think it’s more important to be true to yourself, to be confident and comfortable in projects.

O: And to be honest, as a young designer starting out, you have to be a bit of a jack of all trades, because you can’t pay the photographer, you can’t pay the manufacturers, you can’t be just the graphics guy and expect to be able to produce work. Luckily, I have an engineering background so I am comfortable with figuring out connections and working with machines, and so I’m not afraid of trying to make things work. I think it helps a lot in realizing our projects. It’s absolutely necessary, if you work for yourself you have to be able to do everything, you have to be bookkeeper too.

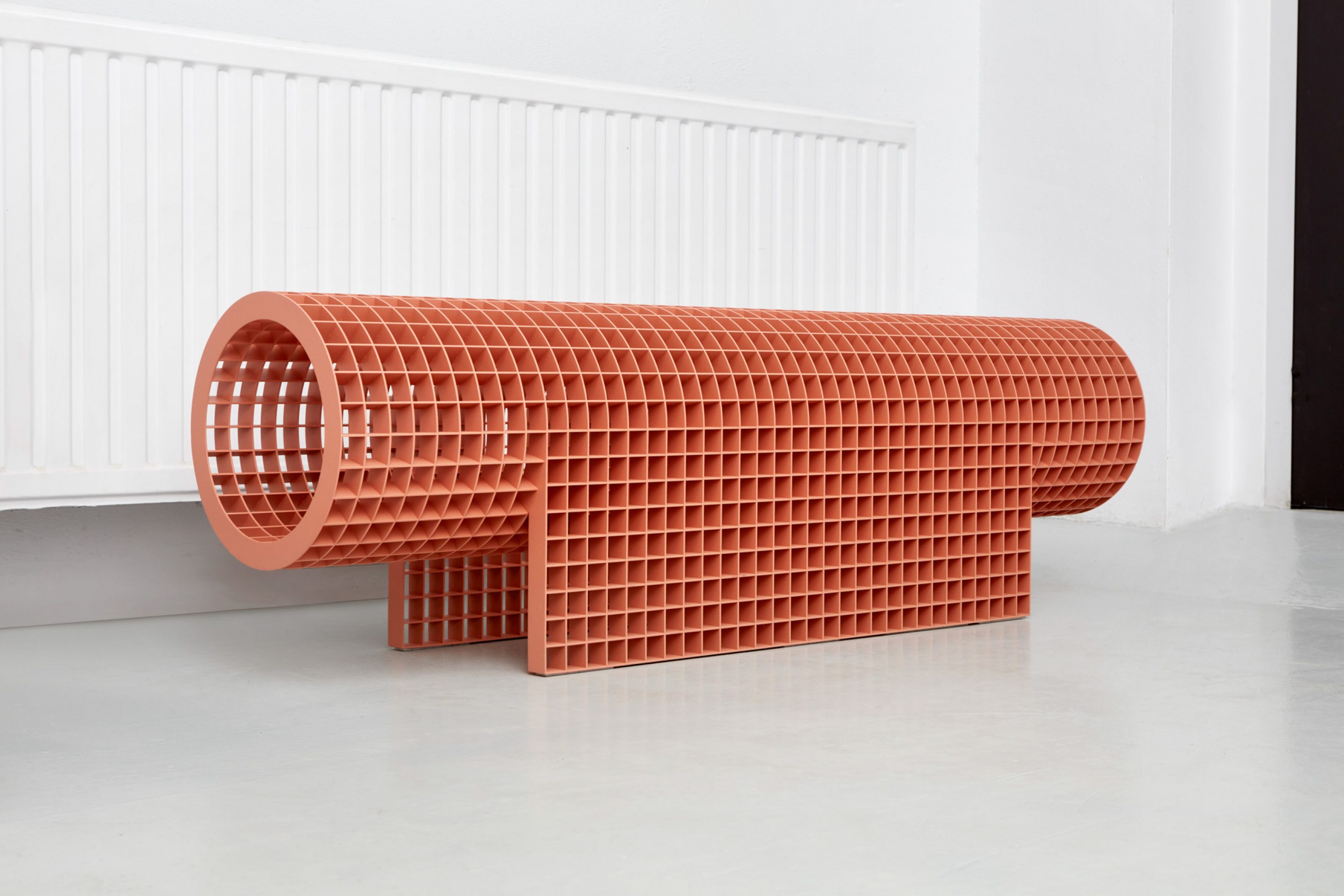

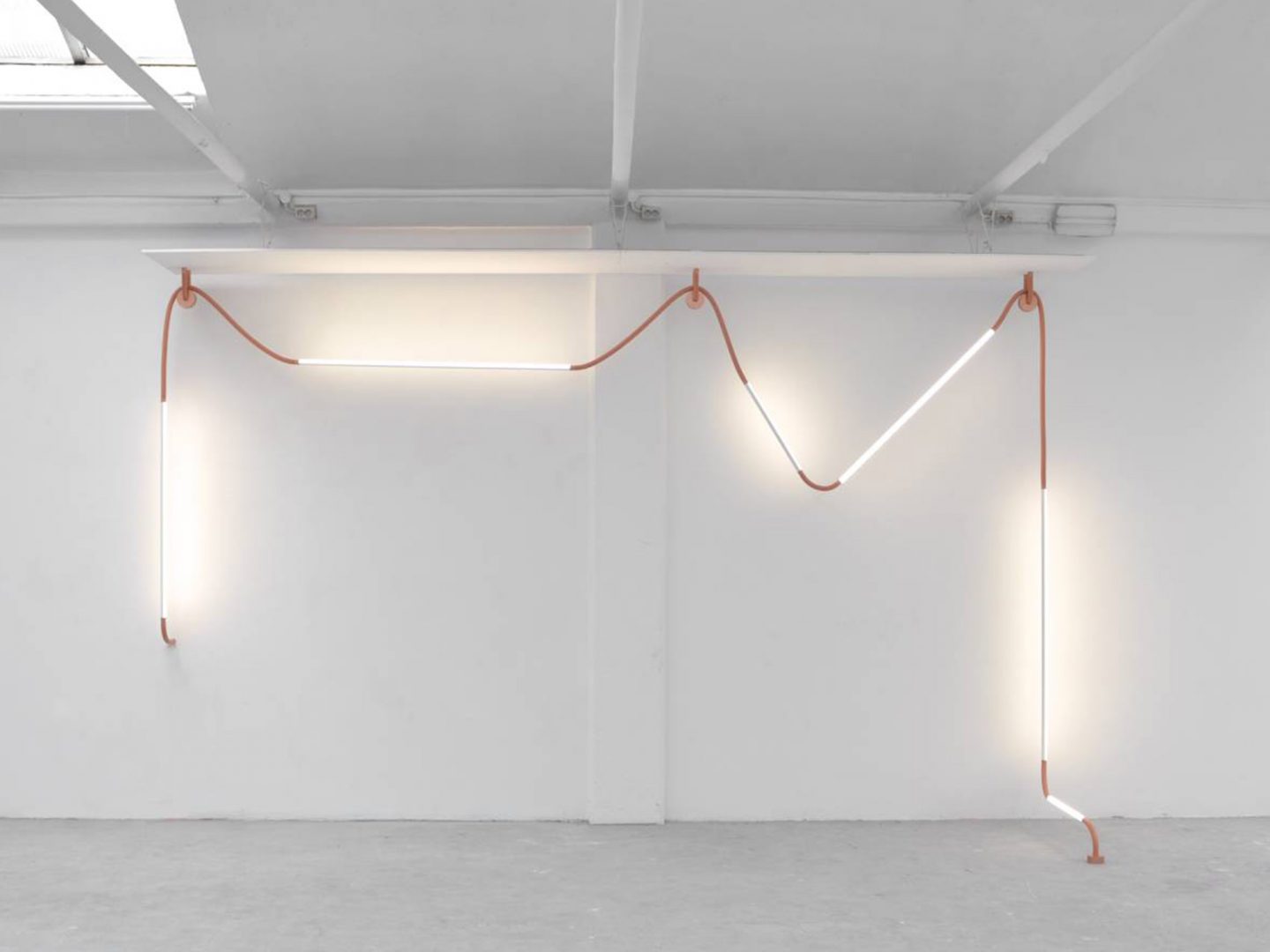

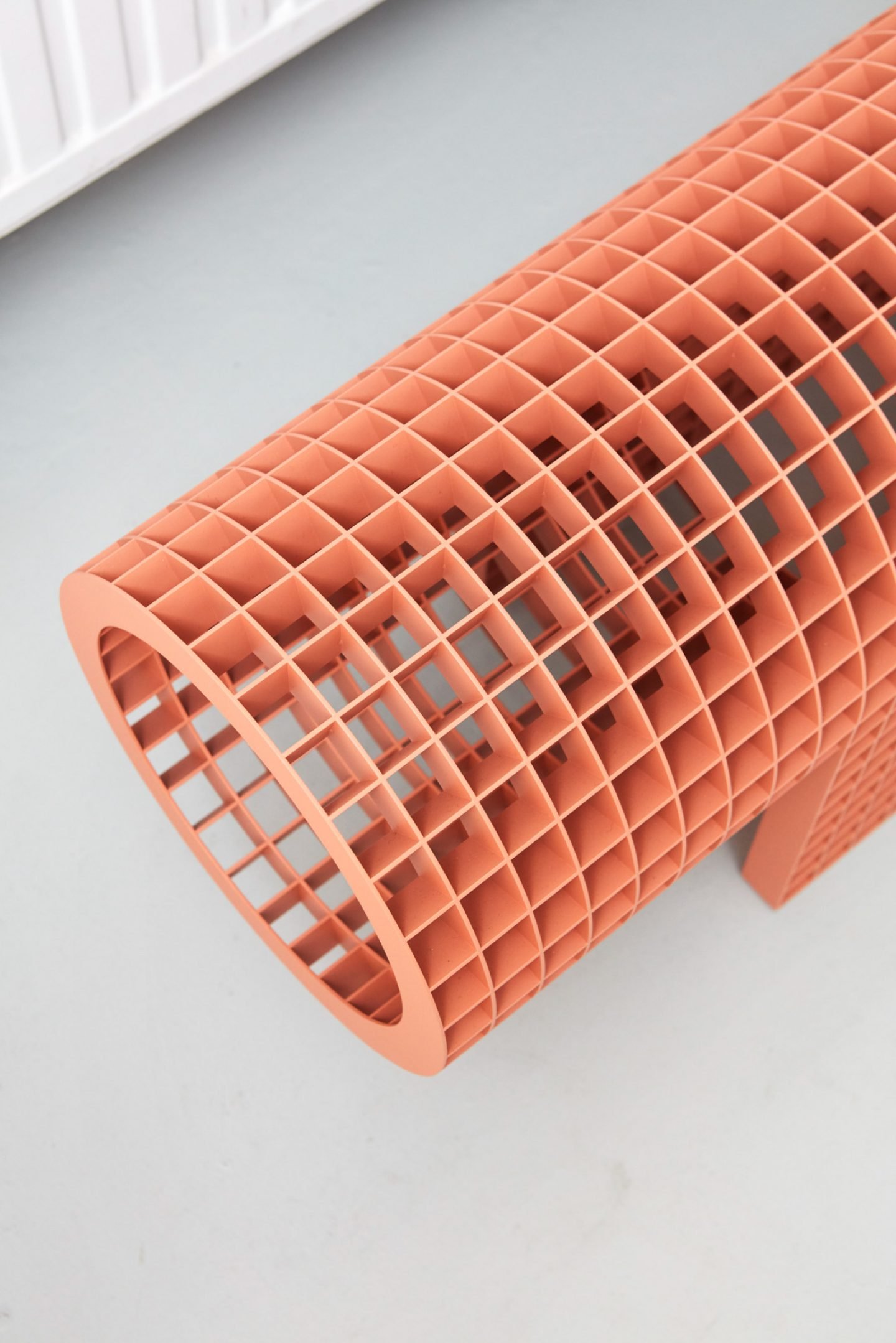

A Selection Of Work From OS ∆ OOS

001 Mono – Light, the Copper Edition

002 Ace & Tate Eindhoven (photo by Jeroen van der Wielen)

003 Ace & Tate Eindhoven (photo by Jeroen van der Wielen)

004 Colouring Table: Concrete

005 Perspective no. 1

006 Heliacal for FontanaArte

007 Side Table of the Thriliton Collection

008 “TALISMAN – Contemporary Symbolic Objects.”

Do you think your skill sets complement one another?

S: Yeah, for sure. I think Oskar is a lot better at making sure things don’t fall apart, and that means when we first start I can think about the shape and the composition and the materials and then Oskar can tell me, “That’s not gonna work”, and even though I know that maybe it’s not going to work we have to go through this process first (laughs)! So it’s a bit faster in that way, and I think we’re quite balanced, I like to make sure that things are running well, but that means doing multiple things at the same time, whereas Oskar is a bit more focused on one thing at a time —

O: I’m not a multi-tasker!

S: — which is ok, because we both have different qualities and when we work on a project we both sit there and go through everything, the entire process is really something that we’re doing together.

"As a young designer starting out, you have to be a bit of a jack of all trades... you can’t be just the graphics guy and expect to be able to produce work."

Where is your name from?

S: Well, actually, the name existed before the Studio! Because we’re also a couple. OS is really easy, it’s for Oskar, and OOS is for Oosje, it’s my nickname. My sister, when she was young, she had difficulty saying Sophie, so she said Oos or Oosje, which is like a smaller version of something: I don’t know if you really have it in English?

O: Yeah, if you add a ‘je’ to any Dutch word it means small.

S: So when we were trying to come up with studio names, we kept on coming back to OS and OOS. Our work was quite graphic at that time, so we didn’t really like the ‘&’ symbol, so we thought let’s change it to a triangle, and it’s something you can also easily type — alt j — and you also get a triangle on your keyboard.

You have remarked that your final products are a combination of art and industry, could you elaborate on this idea for me?

O: Yeah, I think we have always been on the edge between what is design and what is art — I mean, the very first project we worked on could have easily been a museum installation, but it also just functioned as a light, and I think that’s something that we always strive for. I think a lot of people see our work as being minimal, but I see it more as being to the essence, hopefully explaining clearly exactly what its intention is, and what it is supposed to communicate.

It sounds like all of your work is very concept driven, where do these ideas come from?

S: In the beginning, it’s all very vague, and then you start digging into a theme, there’s always a small starting point, of course, this is necessary to start making something. We never say, “Maybe we need a chair in our collection because we don’t have any”, you know — it doesn’t work for us to create in that way.

O: It doesn’t make sense for us to work to create something that is just an aesthetic.

S: It’s a feeling or a material or a color, or a size even. It can be very simple! And then we start digging, and then it’s more like digging into yourself, and at the same time I mean, we have inspiration from architecture, art, nature, it can be anything. You have this idea in your head that you are trying to grasp, and all these small things, it’s like a puzzle and in the end you kind of start to continue again, with just a few sketches and materials and ideas and then basically, we sit together and talk about it, and something rolls out.

O: And in a way the materials that we choose, it’s just then logical. You sort of know what you want to make, the materials you choose are the materials that suit the purpose best. If it needs to be heavy, then concrete, if it needs to be transparent, then glass, it all depends on what it needs to do, and hopefully, you can try and get the materials to have more than just one function, that would be ideal. Then it really makes sense: it has to be that material because it does this and it does that. That’s why it should be there and not another material.

Do you think that comes from not only your own creative ability but also the creative climate of a city like Eindhoven?

S: There’s really an openness in the industry and people are really nice, really easy, and happy to do something different, and I think that’s really helpful for the design industry here. To actually make your ideas happen! They don’t just stay in your sketchbook.

O: I think the Dutch just like innovation, they can’t sit still! The Design Academy plays a big role in that — the students are of course very free, and we learnt, of course, that concept way of working, which I think was typical of the time, it sort of gave us the fundamentals — you know, make sure the story makes sense before you make something. And it’s that combination of being free to combine materials and not really worrying about whether it’s going to work out or not, it’s a ‘let’s go out and try it’ mentality. And then it’s being supported by all of the industry, which is so close by, and people who are actually in the top of their field.

S: When we started here in Eindhoven we thought, ugly city, we’re probably never going to stay here, but it’s actually just got better and better over the years…

It does sound like a hub of innovation —

S: Yeah I think Eindhoven was always growing, so it also means a lot of smaller companies, like coffee shops, or stores, they are really popping up now in the center, and you’re going into a city — I mean, it’s still not a big city, but it’s become more a city where you can do all of the things that you would maybe miss just like in Amsterdam or Rotterdam. When we started studying there was only one place where we could go and get a sandwich for example, and now there is already so much to choose from. And a lot has changed, and it’s good for us here.

O: It’s a rewarding space. Just put it this way, Eindhoven is becoming more and more difficult to leave.

"Just put it this way, Eindhoven is becoming more and more difficult to leave."

All images © Ronald Smits for iGNANT Production