At Home With AA Bronson: A Pioneer Of Conceptual And Queer Art

- Name

- AA Bronson

- Images

- Daniel Müller

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

“My mother always claimed that I announced at age three that I was going to be an artist; really then, the whole story starts from there.”

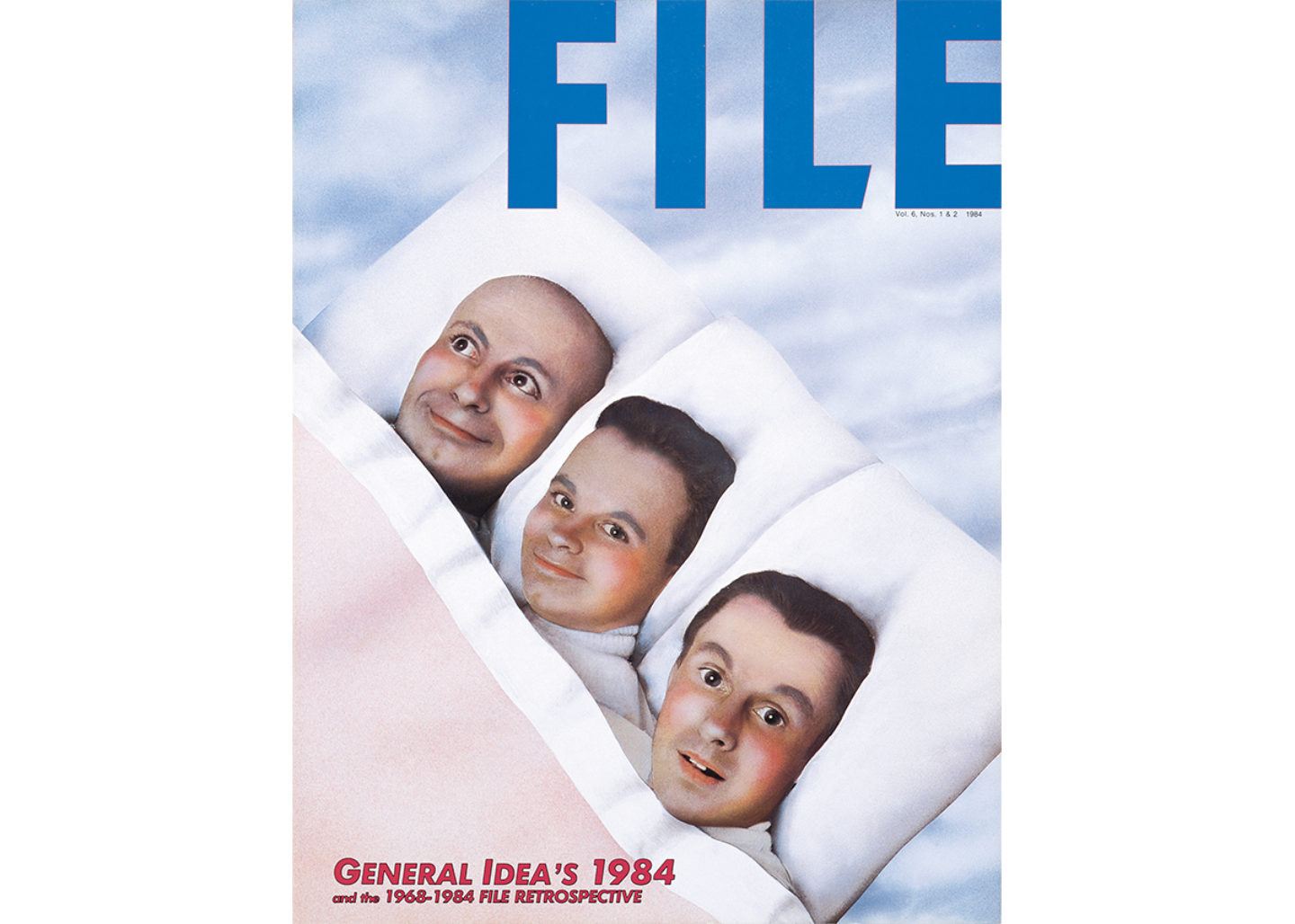

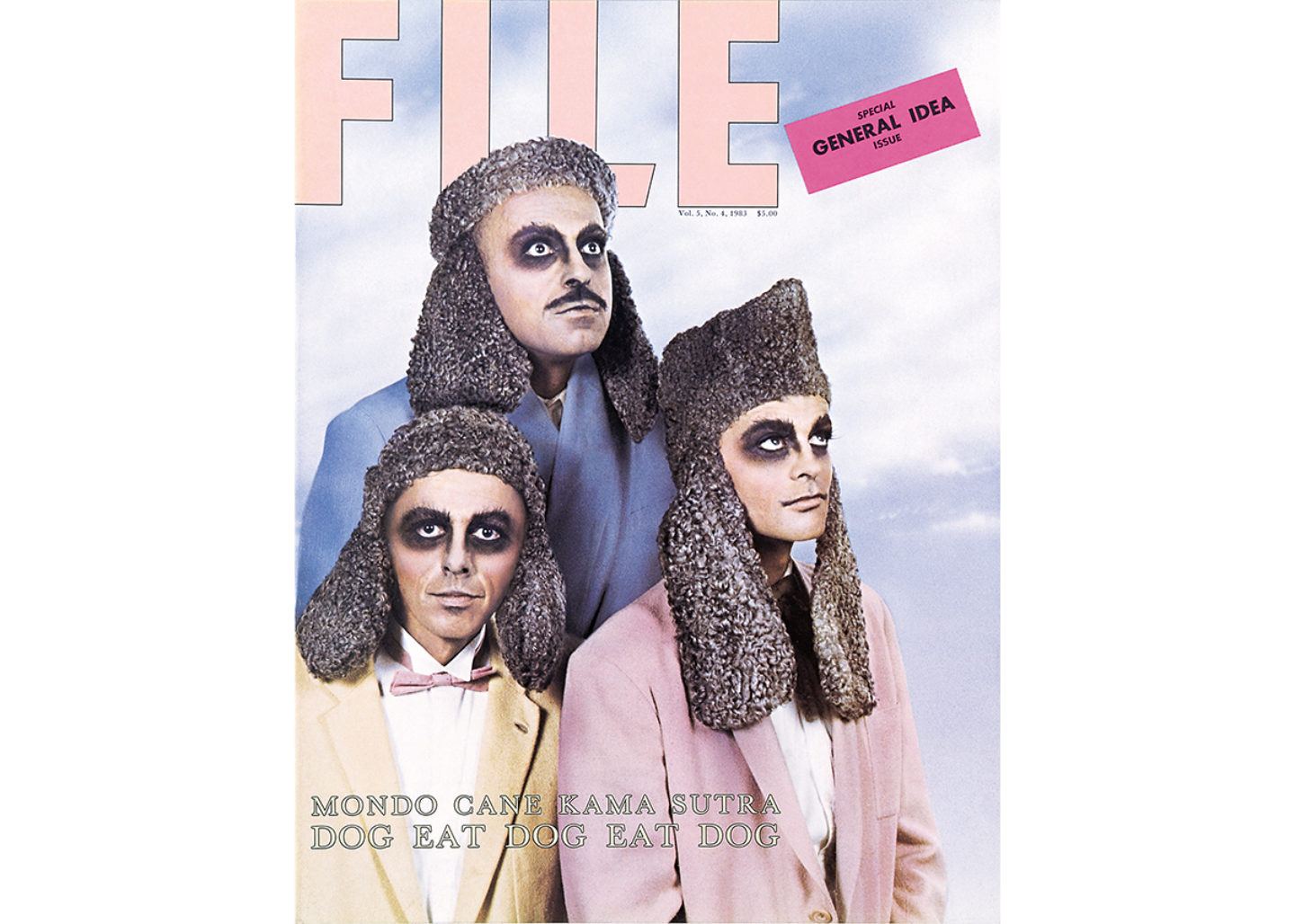

The whole story is no short-read; at 72 years old, AA Bronson (born Michael Tims) has had an artistic career that spans not only decades, but identities; both singular and collective, and mediums as disparate as shamanism and curation. He is the sole surviving member of the art collective General Idea (1968-1994), and is the founder of FILE (published from 1972-1989), a magazine whose first subscribers included Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol; of Art Metropole, an artist-run publishing and exhibition platform; of Printed Matter’s famed Art Book Fairs in New York and Los Angeles; of The Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice; and of the School for Young Shamans.

“At its core, his work has always been about generosity, not about taking”, his husband, fashion designer and architect Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur, explains. We’re visiting the couple at their home in Berlin: a high-ceilinged Altbau that smells slightly like burnt sage—a fitting redolence given AA’s history of conversing with spirits. Over the course of the morning and multiple coffees, the couple generously share with us stories of art, pain, and healing; granting a small window into the world of AA Bronson—a pioneer of conceptual and queer art.

“At its core, his work has always been about generosity, not about taking”

“I never really changed my mind [about being an artist] except in the ’60s when it was time to go to university”, AA explains, “and in the ’60s—being as socially conscious as they were—I decided it was too selfish to be an artist, so I went to architecture school because I thought I could better help people that way.” Noble as his intentions were, AA quickly realized his energy was being poorly directed. He left the University of Manitoba, and with a collection of friends began a commune complete with free school and free press. Today, this act reads as a motif for AA’s creative practice as a whole—concerned as it is with community, radical education and publishing.

“It just evolved because it was fun”

It was also a combination of these things that brought AA into contact with Felix Partz (born Ronald Gabe) and Jorge Zontal (born Slobodan Saia-Levy) in the late 1960s. The three were living in Toronto and crossed paths because of their involvement with the experimental commune, Rochedale College. During this period, a mutual friend convinced them to move into a house together. There, General Idea was born. “It just evolved because it was fun”, AA explains with a laugh. “We lived around the corner from a nurses residence, and there were several bookstores in the neighborhood, and one day one of them threw out boxes and boxes of nurse romances. So we made a kind of nurse romance bookstore in the store window of the house, and put a little sign up that said ‘back in five minutes’. We were always closed of course, and would hide behind the window and, you know, wait for the nurses to come by.”

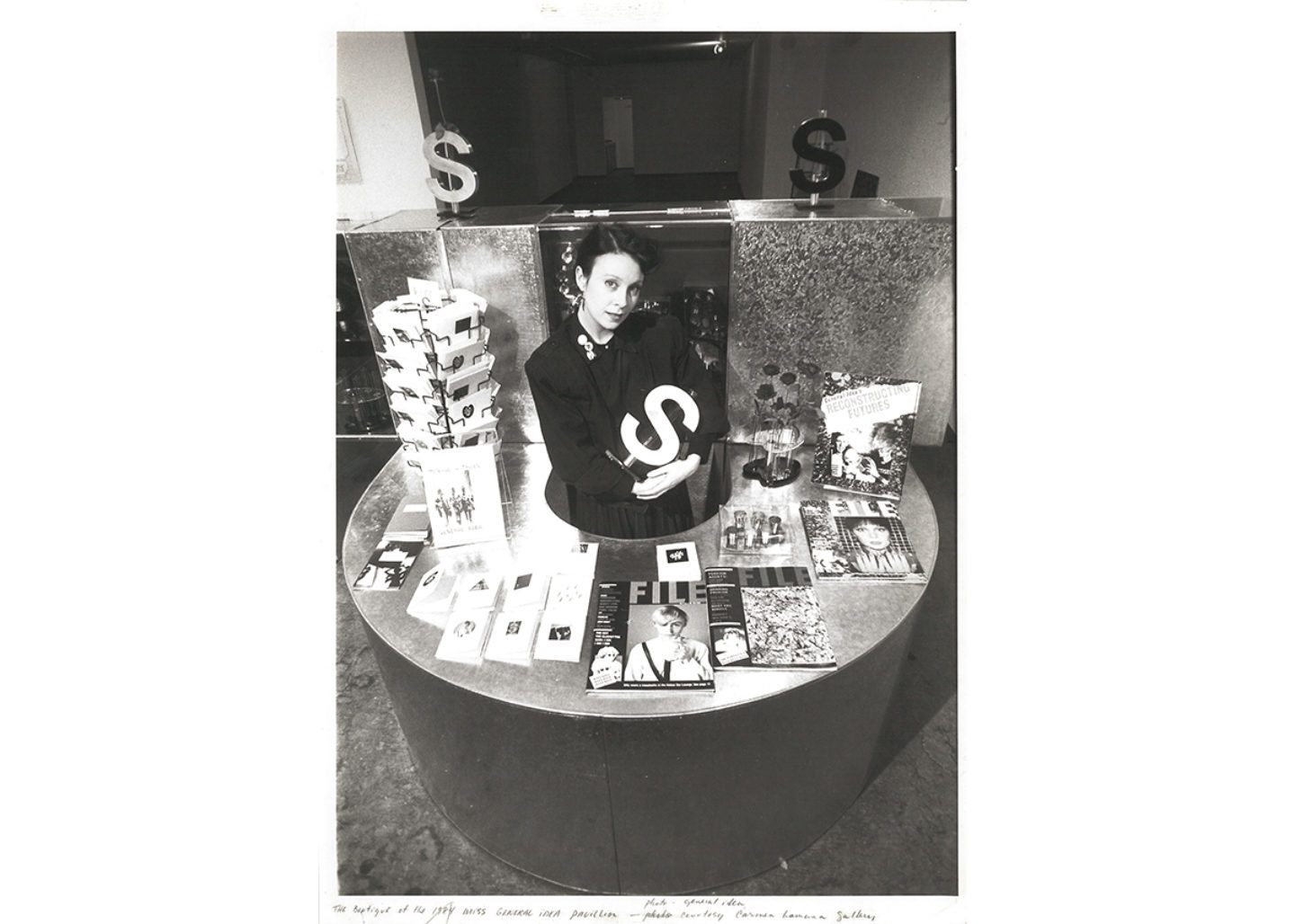

This early project gives insight to General Idea’s creativity. Seemingly unbound to a single genre, their emergence as a queer collective of three challenged more than just heteronormative conceptions of relationships. Utilizing humor and criticism equally, they staged beauty pageants, opened themed boutiques, and created TV talk shows where they were the stars—upending gender ideologies and subverting pop culture and media in the process. Determined to create art outside of white cube conformity, they produced and distributed material in unconventional ways. They established an underground press, and disseminated magazines, posters and postcards to their audience via mail out. Every part of their art seemed personal, and every part of their life seemed like art.

“I guess we never really thought of ourselves as activists. We were just trying to create visibility for a disease that was not being talked about.”

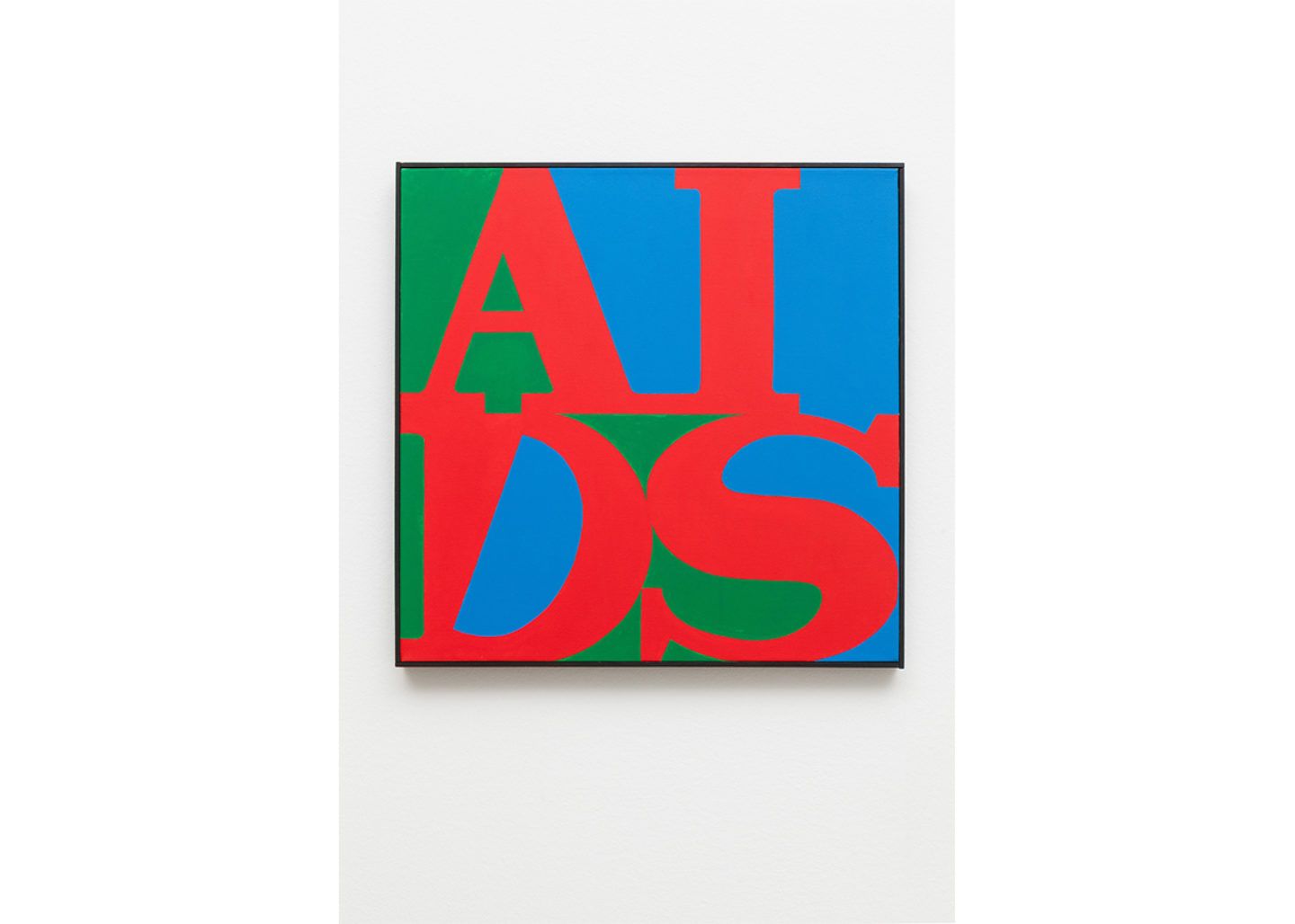

Today, they are best known for their response to the AIDS epidemic that swept America in the 1980s—a crisis that would cause the tragic deaths of both Felix and Jorge in 1994. During these years, personal politics became inseparable from General Idea’s creative output: “I guess we never really thought of ourselves as activists”, AA explains. “We were just trying to create visibility for a disease that was not being talked about.” Their reinterpretation of Robert Indiana’s ubiquitous ‘LOVE’ is as striking as it is heartbreaking. Replacing Indiana’s letters with the AIDS acronym, it somehow represented the unspoken nature of the disease. Visually arresting, colorful and insistent, it refused to be silenced. “For the first few years it was just the word, and nothing else”, AA explains. “You know, we didn’t deliver any other message, it was a kind of void, people would interpret it to mean multiple things; it was unique and powerful in that way.” Later, their pieces about AIDS took more personal form; colorful pills inspired by the medications that populated their home, intimate portraits of Felix and Jorge, bodies ravaged by AIDS.

A Selection of Works from AA Bronson and General Idea

1. AA Bronson, Felix, June 5, 1994 (1994/1999), image © AA Bronson

2. General Idea, AIDS (1987), image © Andrea Rossetti

3. General Idea, Anya Varda Presents Liquid Assets at the Boutique from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion (1980), image © The Estate of General Idea

4. FILE Megazine, volume 6, issue #1-2 (1984), courtesy AA Bronson and Esther Schipper, image © The Estate of General Idea

5. FILE Megazine, volume 5, issue #4 (1983), image © The Estate of General Idea

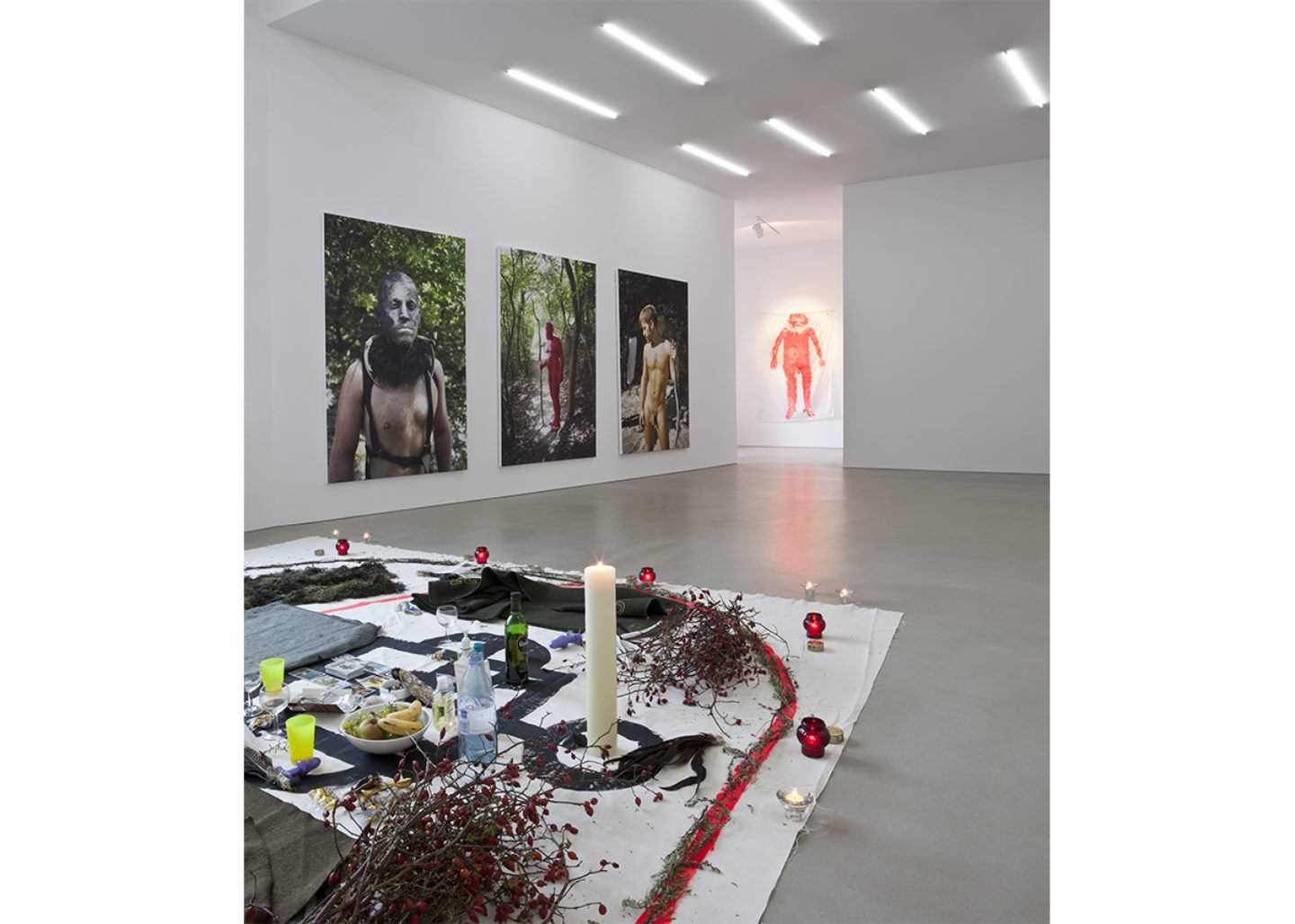

6. Exhibition view: AA Bronson, Queer Spirits and other Invocations…, Esther Schipper (2011), image © Andrea Rossetti

7, 8. AA Bronson, Voodoo Doll (AA Bronson and Mark Jan Kray- enhoff van de Leur) (in collaboration with Rei- ma Hirvonen) (2013), image © Andrea Rossetti

All images courtesy AA Bronson and Esther Schipper Berlin

“Well, I think the whole AIDS endemic really took that out of me. There are too many important things that we need to think about now.”

As silence around the disease mounted the death toll rose, and AA’s interest in healing was given greater purpose. Where midwives had traditionally brought new life into the world, it was suddenly necessary that they help ease pain as life departed—and so AA began training to be a midwife for the dying. It is difficult, if not impossible, to comprehend the effect of such experiences on a person. His work, Mark tells us, changed notably as a result: “General Idea was distant, playful and ironic—but that is gone now. Your work today is sincere and open, you’re no longer distant in the way you were.” Taking a moment, AA replies: “Well, I think the whole AIDS endemic really took that out of me. There are too many important things that we need to think about now.”

His solo work has interrogated such things: focusing on outsider topics related to healing and spirituality, queer identity and marginalization through a creative prism that combines Tibetan Buddhism, shamanism and ceremonial practice with the enlightenment of age and the humor of youth. “You know, in psychological terms, it is always seen to be a problem if someone has multiple personalities”, AA tells us, laughingly. “But in a way, I think everybody is made up of multiple aspects, and some often fight with each other. And, you know, at a certain point I realized that I needed to get them all working together, because then it works—especially if they’re having a good time.”

‘Invocation of Queer Spirits’ exemplifies this synthesis of selves: part performance, part ritual healing, the multifaceted work was created by AA and Peter Hobbs between 2008 and 2010. The work comprised of a series of secret séances that were carried across North America over a period of two years. At each séance, a small group of men invoked the queer and marginalized histories of the location; contemplating exclusion and violence both past and present. ‘Invocation of Queer Spirits’ is an artwork—but it remains mostly undocumented, and few anecdotes from the experience have been shared. This is characteristic of AA’s mode of working: as the art world moved towards capitalist modes of production, he created art that opposed saleability. It is in part, he explains, a response to the cultural climate of New York, where he lived for 27 years before relocating to Berlin in 2013: “There was so much emphasis on selling in New York… everything seemed to have dollar signs attached to it, so I very purposefully started to create work that couldn’t be sold, couldn’t be collected and in some cases, couldn’t even be seen”.

Despite this ‘unknowable’ element to his work, there is a spirit of inclusivity to it too. During his tenure as the director of Printed Matter (2004-2010), AA launched the New York Art Book Fair: an annual event widely credited with cementing independent publishing in the mind’s eye of popular culture. When everything pointed to the end of print, AA saw things differently: “As art gets more and more expensive, the book is the natural next step for something that can be shared more easily”, he explains. Indeed, from the illuminated manuscripts of old to the artist books of new, there has always been a link between the printed page and visual art. And as the commercial art world booms, somehow, independent art book fairs do too. “A friend of ours made such an interesting comment about it,” Mark tells us, “he said if you go to an art fair, it’s really tense because there is so much money at stake and so much social pressure. But, at the art book fair, everybody has a smile on their face and everybody is happy—and I just thought that was such a good observation.”

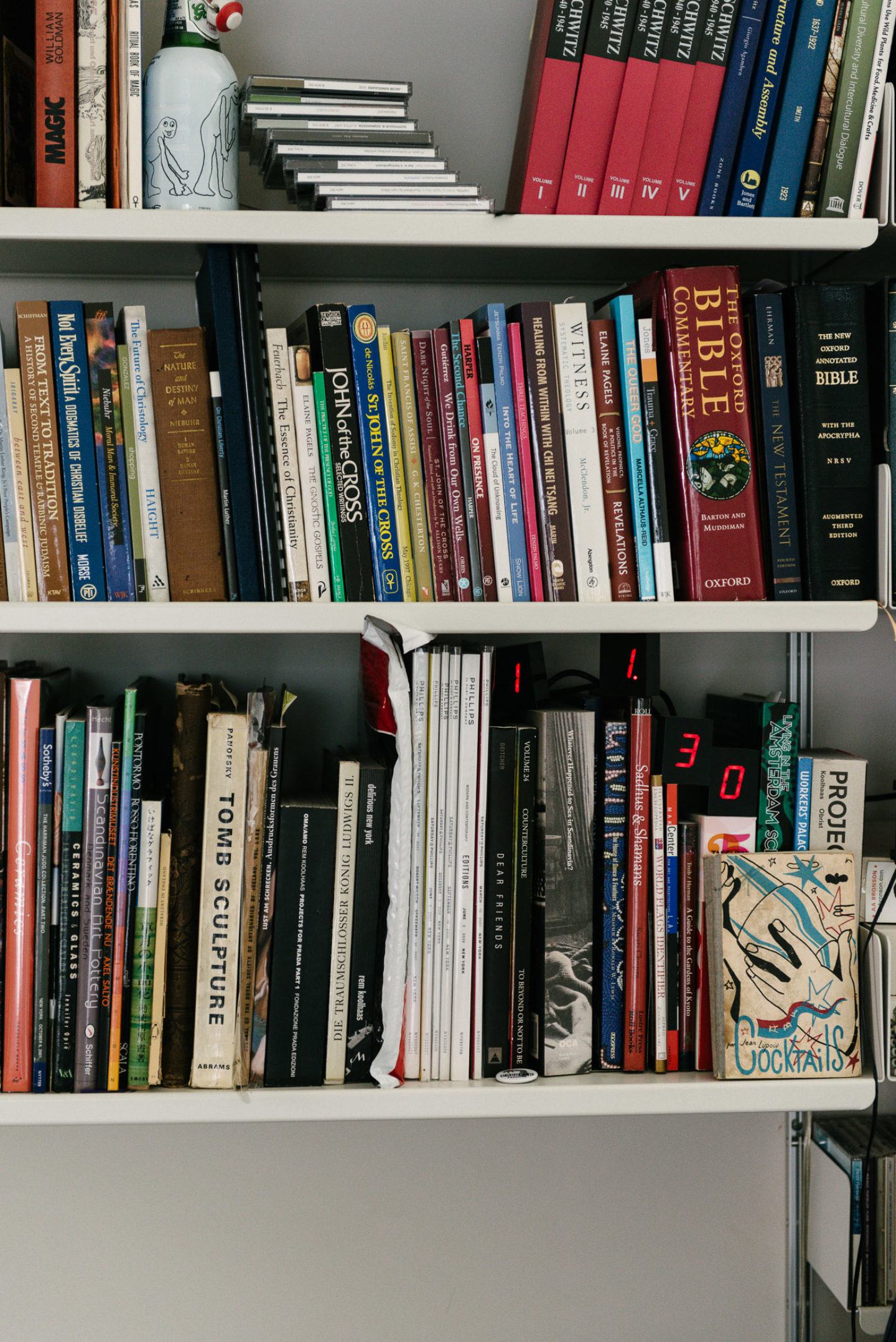

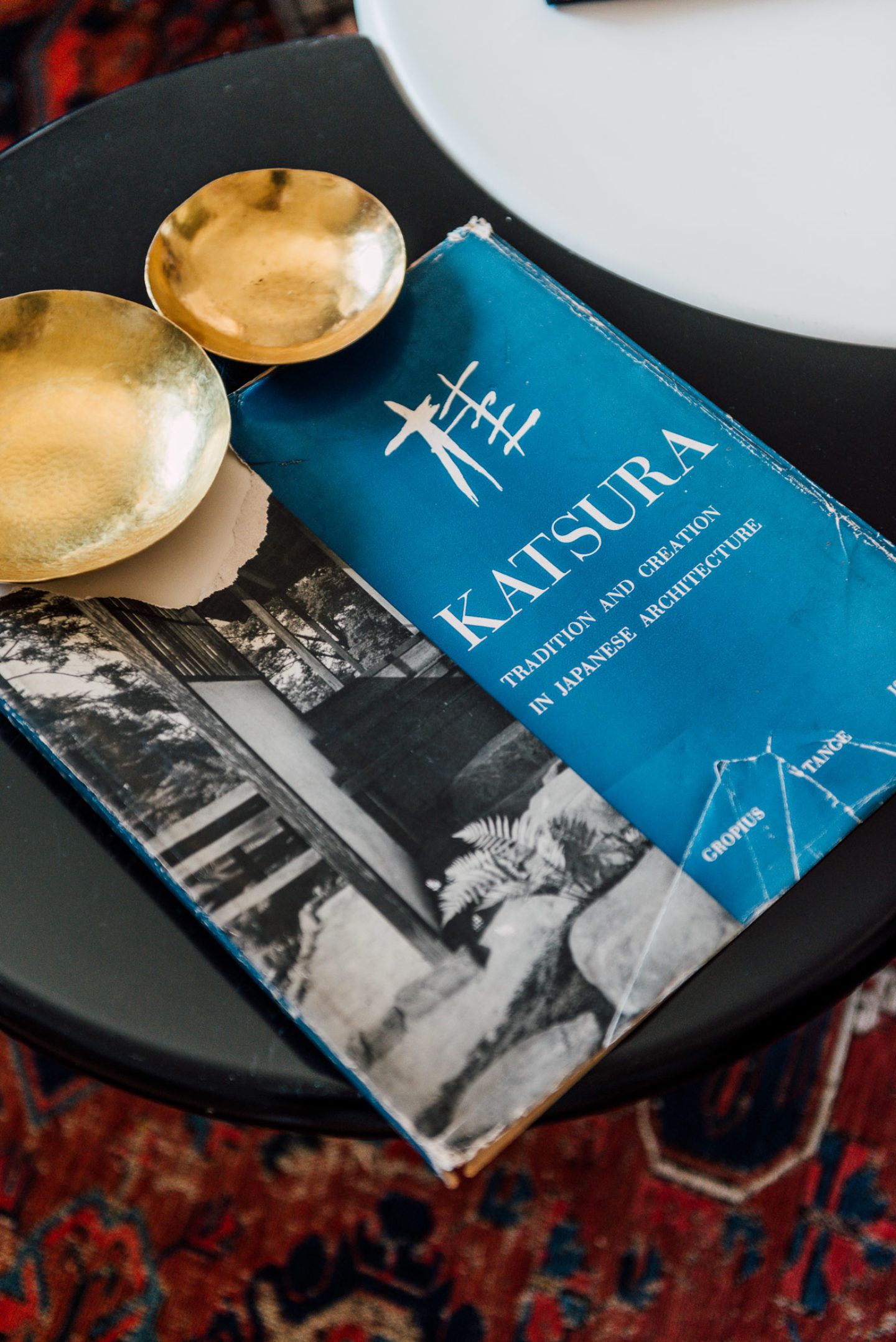

It’s a feeling that is obviously true for AA, who walks to retrieve a copy of his favorite book for us to study, smiling widely as he recounts how he first came across it. “I didn’t normally buy books, I normally got them out at libraries, but this one was a book on the Imperial Palace in Kyoto, and it blew me away. I saved up for months, because my father was very frugal with pocket money, and it was a very expensive book, and every weekend I would go to the bookstore and pore through the pages, and finally one week I went and it wasn’t there, and the sales lady said: ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry, I put it under here so that nobody else could get it!’”.

The book in question is Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese Architecture, by Walter Gropius, Kenzo Tange and Yasuhiro Ishimoto, published by the Yale University Press in 1960. When AA found it, it changed something fundamental for him. He calls it his “landmark book”, and returns to it frequently still. Undoubtedly, his publishing exploits have had similar effects on others; as Mark says pointedly, “I used to hear it quite often, a younger person would come to visit AA and would say ‘I just want to tell you that when I was a lonely teenager in a small town, my bookstore carried FILE magazine, and it let me know that there was a life out there and that I could escape from where I was.’”

Though their love of reading remains, neither Mark nor AA need that kind of golden ticket to magically transport them to another place. Berlin, the “ideal queer space” as AA calls it, has become their home. As we finish our coffees, the pair tells us about their most recent visit to the Auslanderbehörde—the foreign office universally feared by those vying for a visa in Germany. “They saw us arrive, and the woman helping us said, ‘Oh, look, it’s the Künstler pair!’”, Mark tells us, laughing. “Yes”, AA says with a smile, “everyone has been so great, it seems we’ve really lucked out here”.

—

AA Bronson and General Idea are represented by Esther Schipper, Berlin, and Maureen Paley, London. General Idea is also represented by Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich, and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Interview by Rosie Flanagan | All images © Daniel Müller for IGNANT Production