Kerry Tenbey’s Tactile And Grotesque Art Aims To Destroy Assumptions About Gender

- Name

- Kerry Tenbey

- Images

- Kerry Tenbey

- Words

- Steph Wade

Describing her work as “creepy and beautiful”, British artist Kerry Tenbey creates subversive pieces that explore the impact of physical spaces on our emotional state, calling attention to the preconceived social constructs that permeate our lives.

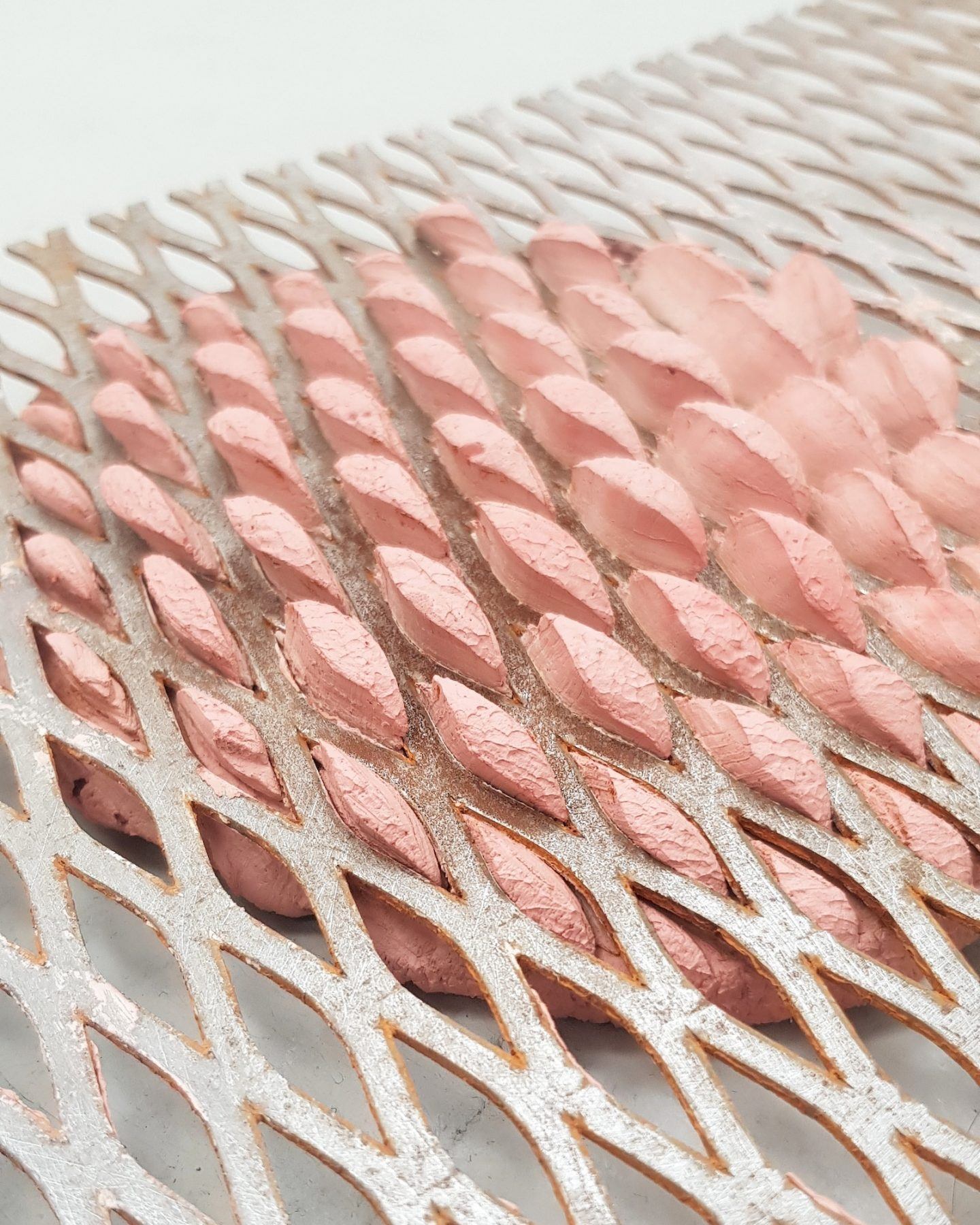

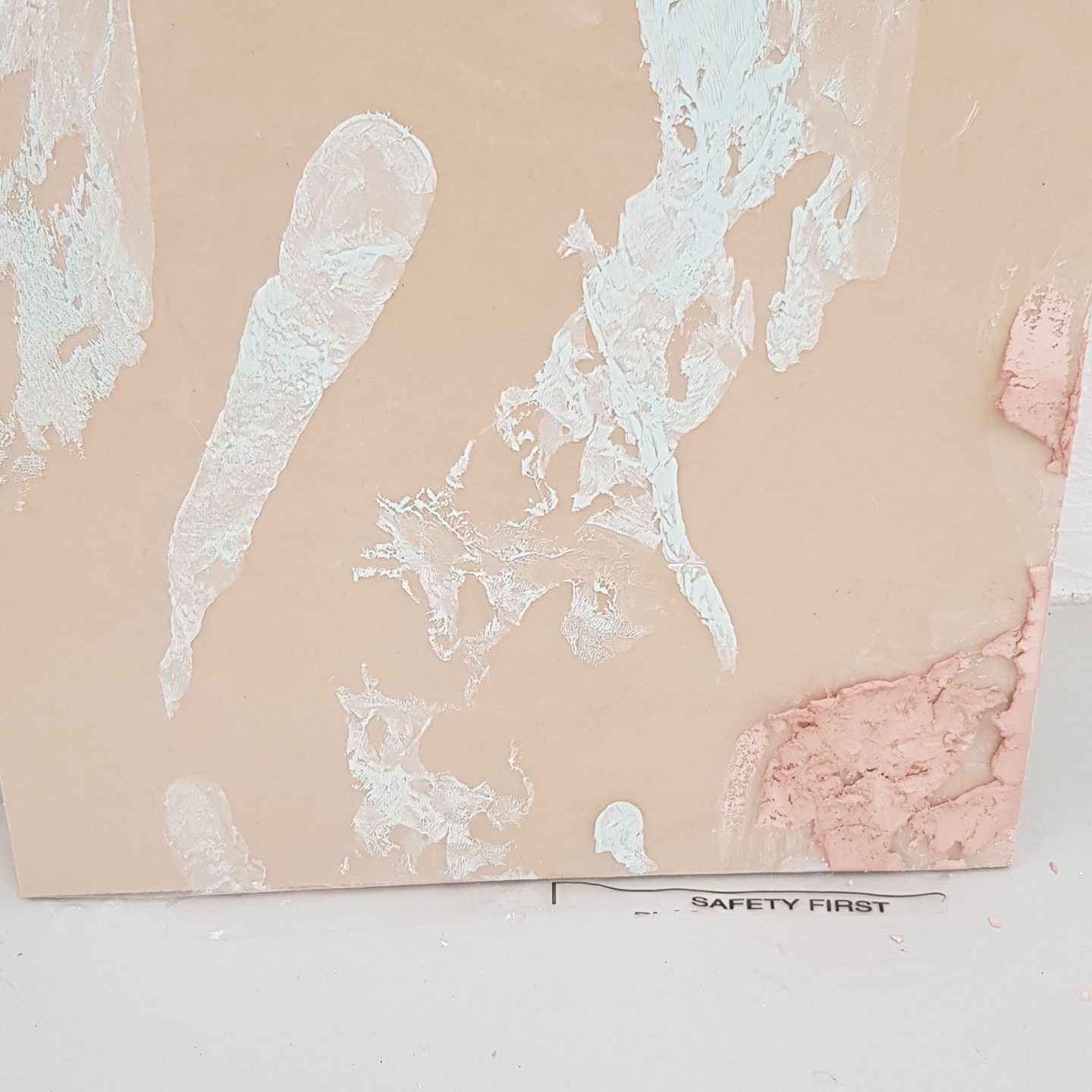

Tenbey’s art directly references furniture, objects, and material compositions that are common in domestic settings. Using a combination of found objects and a plaster and concrete compound mixed in a household blender, Tenbey creates tactile and sensory material forms that aim to overturn ideas surrounding gender, sexuality, and intimacy. Additionally, Tenbey’s perplexing works play with the perception of soft and hard, and the pieces are created in colors that have stereotypical associations to gender, such as pastel pink, in an attempt to reclaim definitions of constructs such as femininity and masculinity.

“We live our lives through a series of situations. We follow schedules, take directions, and navigate through spaces filled with material forms which dictate our movements and interactions”, she says. It’s this tendency to follow habits when occupying spaces that has propelled Tenbey to create her subversive art. We spoke to her about cultural conditioning, destroying gender in art, and why we need to stop categorizing everything.

“I like the outcomes to be playful, slightly absurd, and visually appealing”

How did your interest in the relationship between art and sociology develop?

It has naturally grown from personal intrigue and a desire to investigate the obvious connections between both. Making is my process of understanding, that is, how our social surroundings and interactions can influence how we view ourselves and others. Our entire lives are dictated by navigating through spaces and interacting with objects and functional items, all of which are made, designed or imagined. I am curious about our emotional responses to the materialistic world around us.

Your work revolves around critiquing social constructs of gender, sexuality, and intimacy. How does this desire to question our cultural conditioning affect your work?

It definitely plays a big part in what I make and the processes I use. I try to be very intentional about the materials I use. Materials commonly found in domestic or institutional settings are familiar to us all; we recognize them, they provoke remembrance of times, places, people, and situations. We collectively share memories of bedrooms, bathrooms, train stations, the classroom, the hospital—the list is endless, and all of these settings are the backdrops to intimate encounters. The materials which make up these backdrops play an equally important role in the outcomes of social situations and connectivity. So if you are critiquing these social constructs, you must include all elements in that investigation.

“Materials are gendered and the processes are gendered. I want to destroy those ideas and start over”

How would you define your sculptures?

I actually have a strange relationship with the term ‘sculpture’ and ‘sculptor’, as it sometimes conjures up outdated ideas of tradition and monument. I have taken to referring to my work and self as ‘making’ and ‘maker’ of material compositions that combine made and found objects in an attempt to change outcomes. It’s been said that my work makes you want to bite it to know how it feels. Is it soft? Is it hard? Although I take my investigations seriously, I like the outcomes to be playful, slightly absurd, and visually appealing. I like to play with colors which have stereotyped connotations to gender. Materials are gendered and the processes are gendered. I want to destroy those ideas and start over.

Why is it important to you to call attention to the situations and actions in which material forms dictate our choices?

For me, making is another form of investigation and an experimentation to learn about subjects we do not fully understand, in the same way that scientists or philosophers would do, with endless potential outcomes. Calling attention to our connections and shared energies with the specificities of material forms is important in re-coding our preconceived understanding. Why, when we see a soft pink fabric, do we suddenly think of femininity? The importance lies in the process of re-learning what our surroundings mean to us and how they impact the way we categorize everything, using antiquated, made up concepts.

All images © Kerry Tenbey