In Conversation With Bram Vanderbeke, The Belgian Designer Whose Work Translates The Rhythm Of A City

- Name

- Bram Vanderbeke

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

Cities are growing ever-more populous; and with less ground space in urban centers, we’re building up instead of out. To most, such development can seem confused and claustrophobic, architecturally cacophonous. To Belgian designer, Bram Vanderbeke, even aesthetically obtuse urban landscapes are a source of inspiration.

“I am fascinated by the scale, materials, and colors of a city”, Vanderbeke explains. “I like the mix of different styles, heights, and rhythms.” Where others might see chaos, he finds cadence—something that he replicates in his own practice; crafting pieces by hand from industrial materials, each designed with repetition and rhythm of a city in mind.

The connection between building as a trade and Vanderbeke’s practice is powerful; its presence evident in the striking, but unlikely material forms that his work takes. “My grandfather was a bricklayer,” Vanderbeke tells us, “and as a kid, I was always building things with stones out of his atelier. For me, it was a very logical choice to go to a technical school where I learned to work with my hands. When I went to Design Academy in Eindhoven I rediscovered the workshops and learned to materialize concepts by making. I still work as a maker and I’m also sure that my fascination with industrial materials comes from my background. I love to use bricks, concrete, and reinforcement steel to build things.”

Image © Paul-Lou Koci

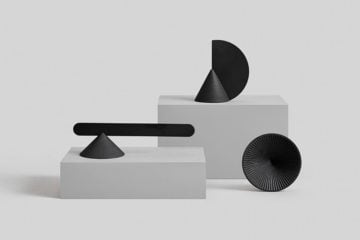

Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu, 'Fat and Regular Pyramid' (2018) | Image © Wendy Andreu and Bram Vanderbeke

Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu, 'Fat and Regular Pyramid' (2018) | Image © Wendy Andreu and Bram Vanderbeke

Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu, 'Fat Pyramid' (2018) | Image © Alexander Popelier

Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu, 'Fat and Regular Pyramid' (2018) | Image © Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu

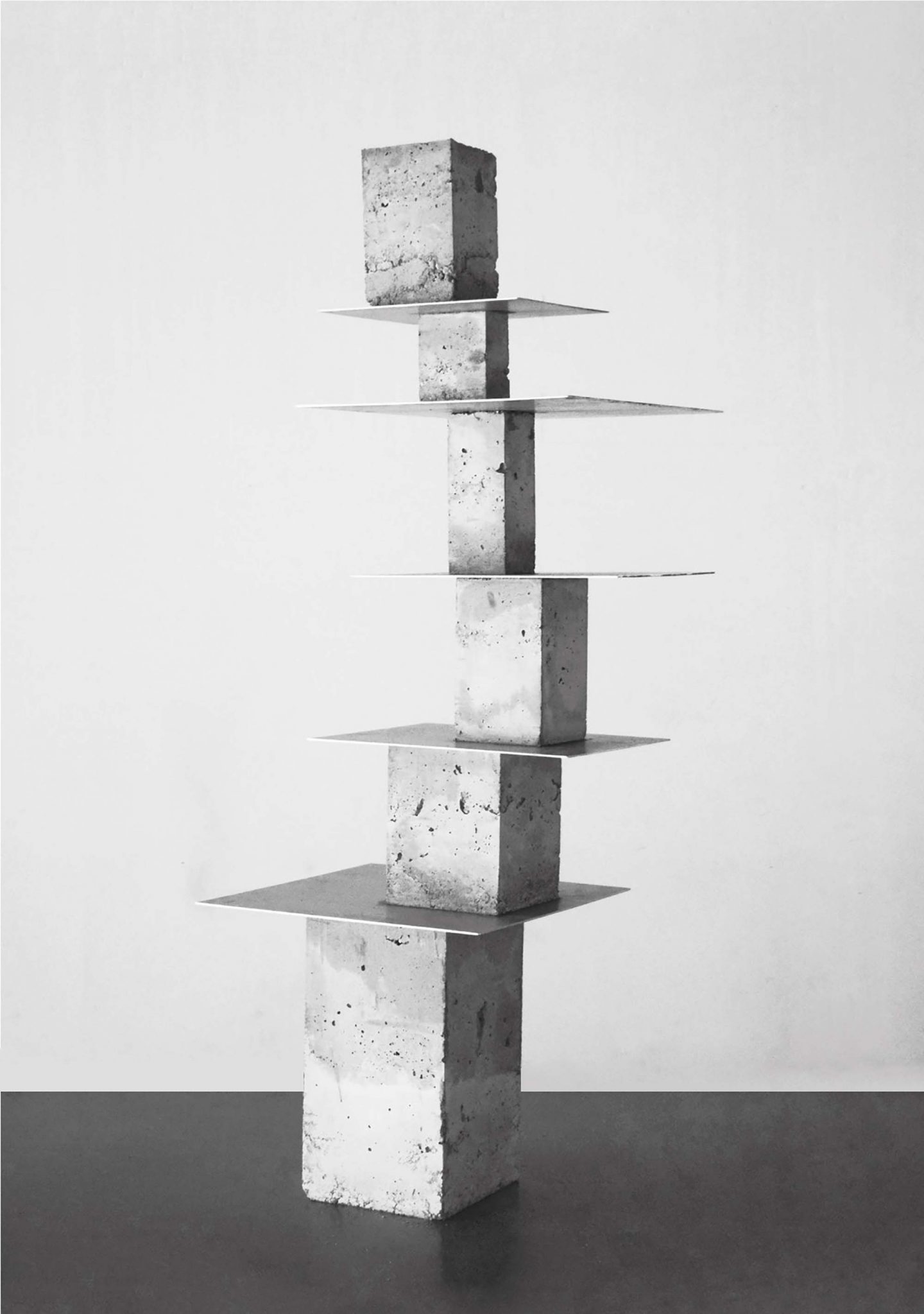

‘Casted Objects’ (2019), and ‘New Primitives’ (2018) are illustrative of this influence; both collections are crafted from typical building materials—the former, bricks, and the latter, concrete blocks. “The process of the ‘Casted Objects’ project felt very close to building things with brick leftovers as a kid”, Vanderbeke explains. These architectural furniture pieces were created using a construction technique where concrete is cast from brick-molds. The result is a collection that pays textural homage to the materiality of bricks and the laborious processes of building. Conversely, the pieces of ‘New Primitives’ (2018) have been sculpted from large-scale concrete blocks; “an intensive and physical process which is explicated by the scars on their surfaces”, Vanderbeke explains. These pieces have been finished with layers of stone wax, creating an unusual character that presents concrete in a new light.

Image © Ronald Smits

Bram Vanderbeke, 'New Primitives' (2018) | Image © Ronald Smits

“Most of the time I begin with a fascination towards a material, technique or a shape, and I will start to play with that.”

It is not a desire to elevate industrial materials that motivates Vanderbeke’s work; but rather, a genuine appreciation and understanding of them. “Most of the time I begin with a fascination towards a material, technique or a shape, and I will start to play with that”, he explains. “I am a maker, so for me, it is very important to go to the atelier directly to experiment with connections and textures. I will often take the time to analyze these experiments, and imagine them in different contexts to see what they eventually could become.”

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stackables', (2017) | Image © Luca Beel

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stackables' (2017) | Image © Luca Beel

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stackables' (2017) | Image © Luca Beel

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stackables', (2017) | Image © Luca Beel

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stackables', (2017) | Image © Luca Beel

“I am interested in how an object can change or improve the way people use a certain space.”

The relationship between material and space is key to Vanderbeke’s practice: “I am interested in how an object can change or improve the way people use a certain space”, he explains. “I also like to see my works as an intermediate, because I believe in their potential to be multiplied, or scaled up and be placed in a different public or private context where they can have a different impact on the space.” In ‘Barriers’ (2017), Vanderbeke enacted this design philosophy quite literally; creating a series of sculptured concrete barriers and obstacles that were positioned in front of Budafabriek, an event space in Kortrijk. Acting as a pathway, they helped guide people to the building—altering both interaction and experience of the space in consequence.

It seems that Vanderbeke is not only fascinated with physical elements of the urban landscape, but with how we relate to them, and how we navigate them on a pedestrian and personal level. At various points during conversation he mentions his love of walking the streets of cities; an architectural flaneur—concerned not only with the beauty of our built environment, but with the chaos as well.

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stacked' (2019) | Image © Jeroen Verrecht

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stacked I' (2016) | Image © Jeroen Verrecht

Bram Vanderbeke, 'Stacked I' (2016) | Image © Bram Vanderbeke

Bram Vanderbeke and Wendy Andreu, 'Regular Pyramid' (2018) | Image © Alexander Popelier