The Work Of Art In The Age Of Compulsive Reproduction: Two Decades In The Oeuvre Of Wade Guyton

- Name

- Wade Guyton

- Images

- Thomas Pirot

- Words

- Anna Sinofzik

Ever since Wade Guyton started pulling lengths of primed linen through his studio printer, critics have riffed on the technique, comparing it to Warhol’s turn to silkscreens. The comprehensive survey at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne contextualizes the artist’s most pithy method within a multilayered, experiential setup.

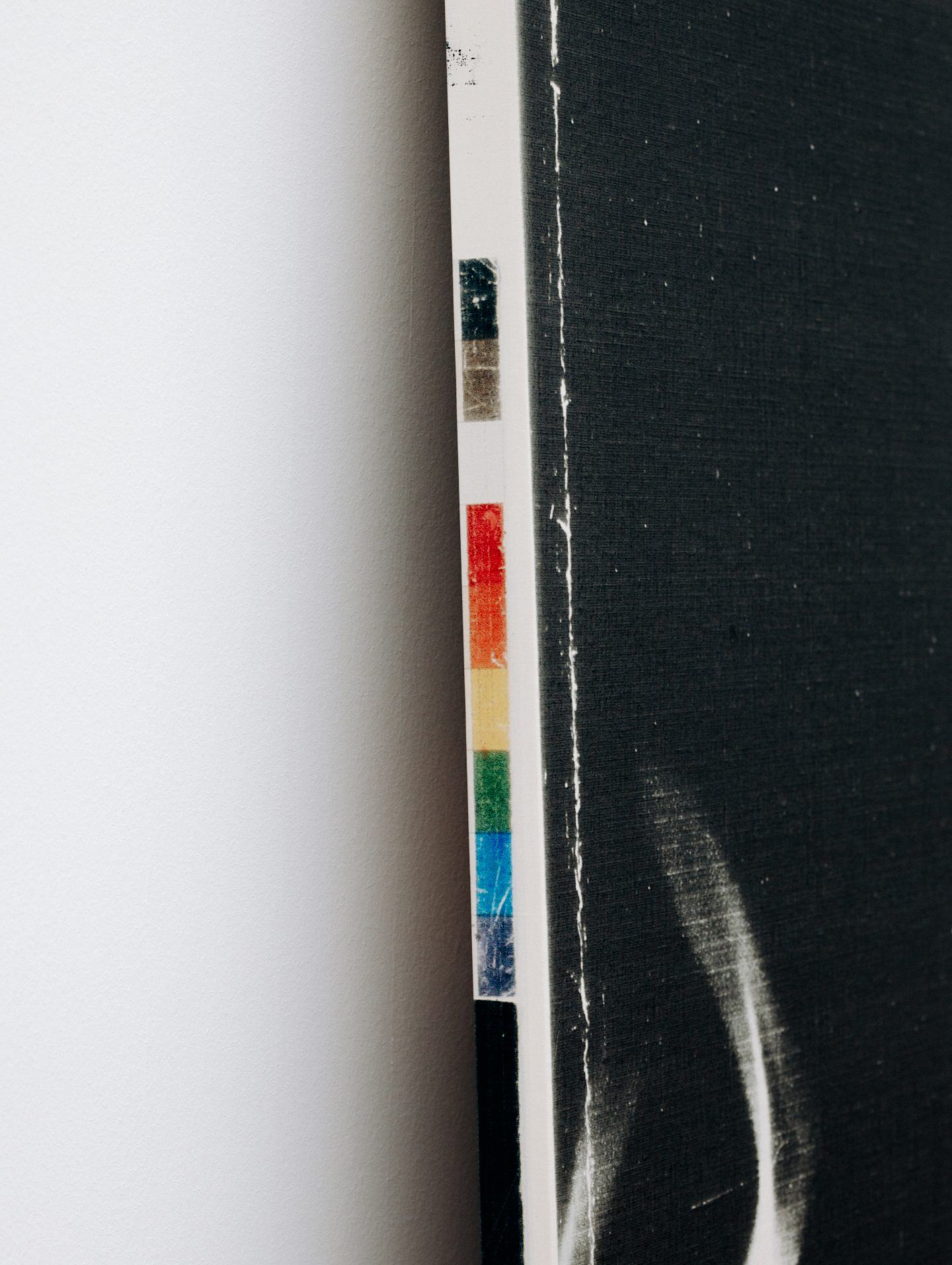

Wade Guyton paints with inkjet printers, draws per air-drop, and bends designer chairs into sculptures. He bends the laws of art historical language, too, referring to his printed works on canvas as paintings, to his smaller paper printouts as drawings, and to scans and screenshots as modes of photography. “There are many ways to capture, transfer and process an image,” the artist notes, addressing the diversity of his Cologne show. Obviously, there are many ways to create exhibitions as well, and this one does not adhere to narrative conventions. Instead, it establishes its own varied rhythm to emphasize the creative range of two decades of production.

“There are many ways to capture, transfer, and process an image”

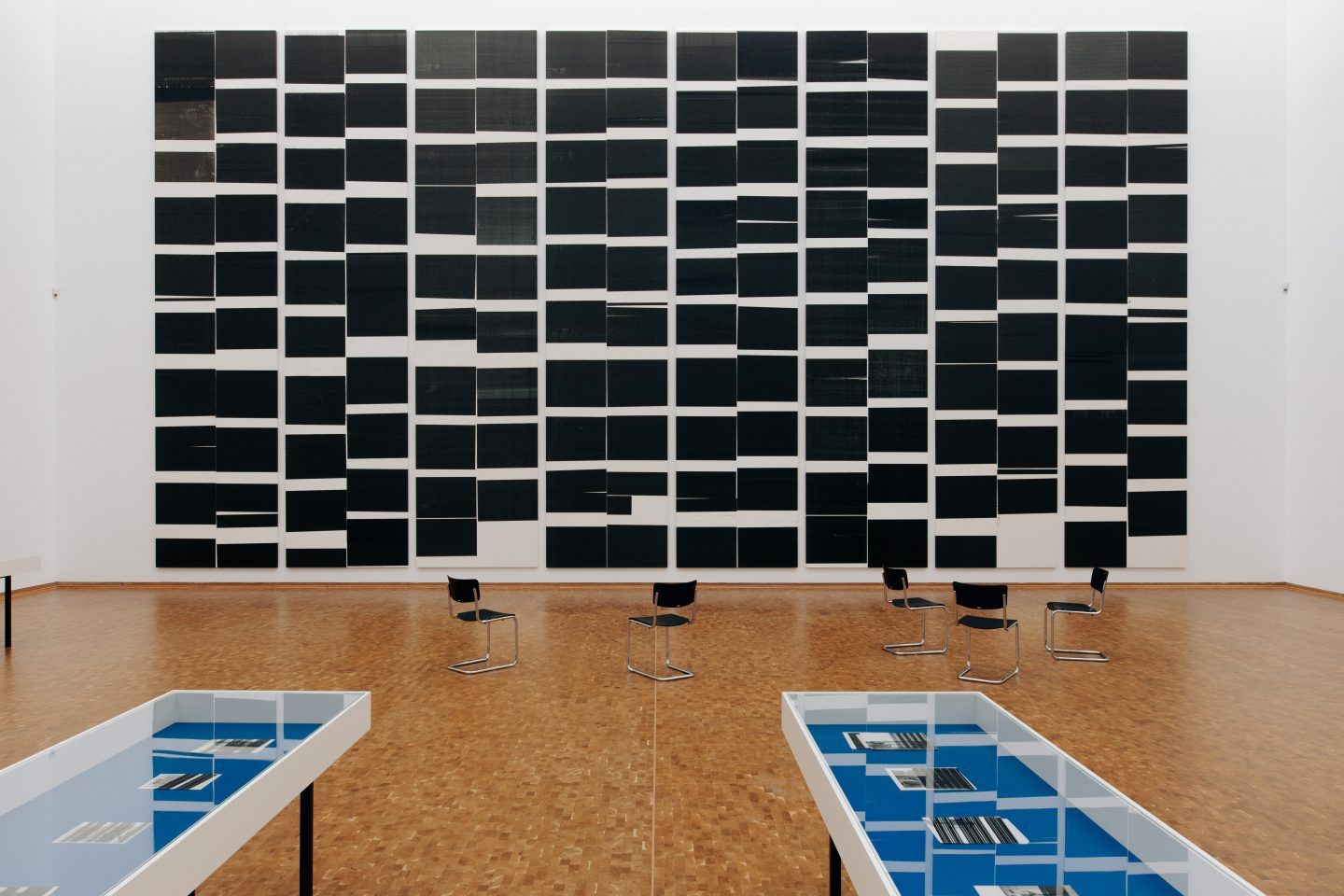

The characteristic architecture of the Museum Ludwig correlates with the exhibition’s nested structure. Its distinct spaces and staircases posed some challenges and predetermined the positioning of some of the largest works, Guyton shares, pointing at a 15-meter long painting made of several panels. But the necessity to really work with the building also brought about new visions of how to organize the exhibits. The result are multiple chronologies that drive visitors forward while sending them backwards in time, too.

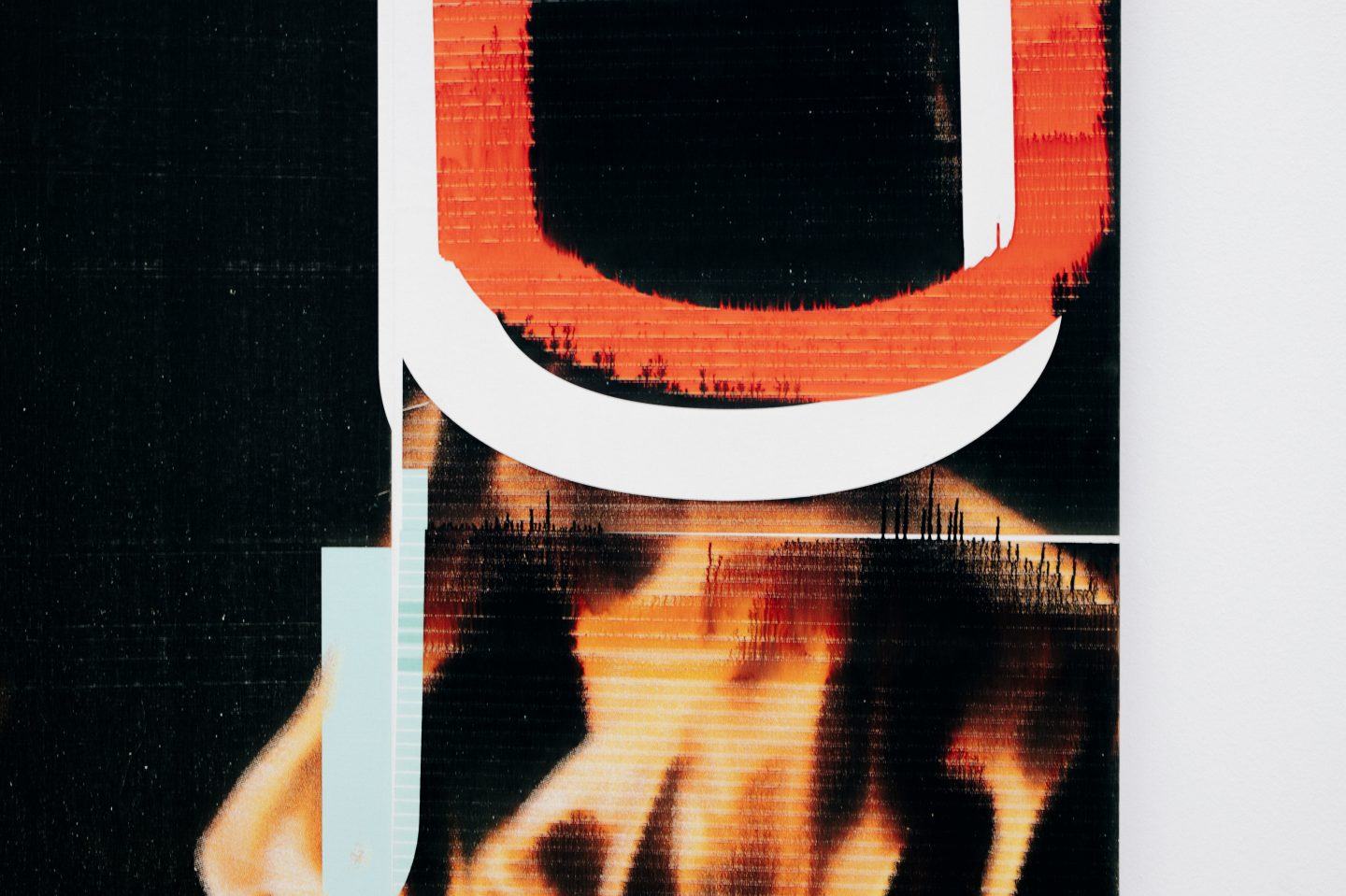

Curated by Yilmaz Dziewior, the museum’s director, Wade Guyton’s survey occupies the entire temporary exhibitions space, the DC Hall, and three adjoining rooms of various sizes. Its non-linear setup mirrors the artist’s mode of production and the sense of “compulsive return” that motivates much of his work. “I keep re-opening and re-executing the same image files,” Guyton comments, explaining his process as an ongoing inquiry into material and technological constraints. The sense of circularity, repetition, and compulsion is present throughout the show. Right in the first room, a wall combines fire paintings from a range of years.

Along with other iconic elements, such as his famous x’s and u’s, flashes of fire and flames have spread across Guyton’s work since the mid-1990s, when he arrived in New York City from Tennessee, with no clear idea of what made the city’s contemporary art market tick. The first time he presented his printed works as “paintings” was in 2006, at his aptly titled exhibition ‘Paintings’ in London. “Once you give something a name, along with it comes all the art historical baggage, but a lot of possibilities and new levels of meaning, too,” he says. Art needs language to be contextualized and, of course, Guyton’s terminology entered art critical discourse as a provocation. Stunned by the seeming simplicity of his process and, perhaps, inspired (or offended) by the artist’s penchant for playing with words, some people dismissed him as a “high-end art director”. Clearly, some people weren’t paying attention.

Many of Guyton’s works emerge from spontaneous, ad hoc decisions or makeshift solutions.

At Museum Ludwig, Guyton’s large-scale inkjet prints on primed linen alternate with sculptural work, display cases with publications, and his overprinted book and magazine pages, which he dubs drawings. Upon closer inspection, the diverse body of work unfolds into a complex feedback loop of forms and citations. One object that reappears—both physically and in the paintings—is the deformed chair by Marcel Breuer. Around twenty years ago, Guyton found one on the street and brought it to the studio. “At the time, I thought I could possibly fix it, but I couldn’t. So, I bent it more and it became a sculpture. That action kept being repeated over the years. It felt as much as a performance as it was an object” he shares. It turns out, many of Guyton’s works emerge from spontaneous, ad hoc decisions or makeshift solutions.

The survey opens with an extensive installation that veils one of Guyton’s large printers as well as a couple of tables and crates in bright blue fabric. “This was originally built out of necessity and formed part of an exhibition in Naples,” he shares. “I had produced all the artwork on-site at the gallery, and for some strange Neapolitan reason, it was impossible to get a truck to pick up all the production materials before the opening. So, we simply covered it all up and it looked pretty good.” In Cologne, the curious construction serves as a pedestal for Guyton’s U sculptures. Beside its repurpose, it dragged along anecdotes, like a lot of exhibits in this show.

“These are sofas from installation at Carnegie International at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, they resemble those I have studio,” Guyton says, pointing at a worn-out leather lounge suite. “I wouldn’t even know if I’d call these artworks. The idea was to not merely bring that painting next to it, but to recreate part of the environment it was first installed in. Apart from this, people need a place to sit down.” There is additional seating, a whole set of chairs the artist bought from the Enron Corporation when it went bankrupt. At first, he wanted to twist them into sculptures at an exhibition in Zurich, but later decided that “they looked great as they are.”

"At first, I didn’t realize those could be artworks at all."

Guyton’s work appears to gather autobiographical clues, much like the human mind gathers memories. However, while many of the artist’s citations relate to his own process or work environment, it would be inadequate to think of them as purely self-referential. Besides personal documentation, broader universal themes and collective experiences also become embedded in his work, most evidently in the New York Times paintings (printed screenshots of the paper’s online edition). One specifically that is part of the Cologne survey shows Trump and Obama shaking hands. A whole series of related works was first exhibited on that fateful Election Day in 2016 (the timing of which being purely coincidental, Guyton remarks).

Guyton’s New York Times and similar “internet paintings” freeze moments in time (e.g. 7:48 AM, 258 comments). Beyond that, their mere object-ness contrasts the increasingly intangible and elusive experiences that dominate our daily lives. “At first, I didn’t realize those could be artworks at all. I was just reading the news and wondering what would happen if I would print them. Then the painting started antagonizing the monochromes that were sitting next to it in my studio and the experience became somewhat unsettling. The energy between these works is really intense—they talk about so many different things,” Guyton shares. His words perfectly describe the energy and tension pervading the entire exhibition as well as much of the world as we know it.

Digital technology and indistinct copy-right laws have set off avalanches of artistic appropriation. But amongst bouts of nostalgia, bland remakes, reenactments, and reconstructions that mindlessly rehash old formulas and found objects, Guyton’s work stands out as a subtle reminder of the complexities and uncertainties of our time. The power of this particular show lies less in the individual exhibits than in the disruptions and relationships between them. With radical shifts in scale and time, interlaced references, nested narratives, and diverse media types, the exhibition creates a familiar sense of fragmentation. Albeit not explicitly, and perhaps unintentionally, Guyton’s manifold oeuvre manages to simultaneously disrupt and reflect the logic of self-refreshing social media feeds, along with their rampant and repetitive image production.

“Obviously, my presence is necessary for my art to become what it is,” the artist declares, when asked about the critical balance between detachment and creative control in his process. For the large paintings in particular, the latter is very physical: any “reprint” is different, depending on how Guyton responds to the file and the way in which he pulls the canvases through his printer. Then again, he likes to delegate large parts of his work to the printer, pulling off a dynamic interplay between his own decisions and the self-reinforcing tendencies of his tools and materials. Harnessing the Cagean element of chance, Guyton’s process involves moments of doubt. As many of the systems we increasingly rely on today, the printer’s data processing unit is run by a black box algorithm. “You never know what comes out of the machine,” Guyton says. “I am always surprised. And often disappointed. Then I realize that what I wanted to do isn’t the right way of doing it. But there is as much doing as there is listening. The artwork tells you what it should be and how it should function. It is very important to stay attentive.”

ADDRESS

Museum Ludwig

Heinrich-Böll-Platz

50667 Köln

OPENING HOURS

Tue-Sun: 10.00-18.00

WADE GUYTON ZWEI DEKADEN MCMXCIX–MMXIX

is showing at Museum Ludwig from the 16.11.2019-01.03.2020.

– This story was produced in collaboration with Museum Ludwig –

All images © Thomas Pirot for IGNANT production