“One Idea Is Not Enough”: In Conversation With Erwin Wurm

- Images

- Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek

- Words

- Kiri Sulke

Austrian sculptor Erwin Wurm is not an artist with a “lifetime concept”. At his studio in Limberg, Austria, we learn how an artist who began his career interrogating the very definition of sculpture remains skeptical of his audience, the intentions of collectors, and the current environmental movement.

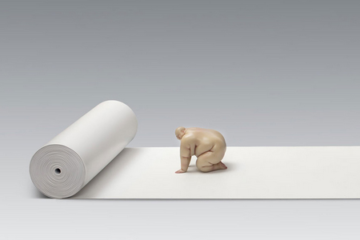

Wurm is more than a sculptor, he’s also a brand. The Red Hot Chilli Peppers featured his ‘One Minute Sculptures’ in their Can’t Stop video and Claudia Schiffer performed a series of them in a Vogue editorial. His ‘Fat’ series—obese resin caricatures of Porsches, VW-Buses and houses—can be found in collections as widespread as MONA in Tasmania, and the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. Wurm is a busy man; every month in 2020 heralds a new exhibition opening of his work. We caught him on a muddy Friday morning in November, when he took the time to personally show us around his studio.

Studio Wurm is located in Limberg; a small, unassuming town in Austria. Concealed by a 12 foot steel door, the studio comprises of Wurm’s workshop, two sheds, an exhibition barn, and an office. In between this amalgamation of buildings stand four large sculptures: headless suits dancing in front of a shed. We are led inside to meet the artist himself, whose movements suggest both athleticism and a sense of urgency. Our tour begins as soon as we shake hands: Wurm briskly walks us through the enormous shed, naming different sculptures in quick succession. He pauses at a mid-century cabinet mounted on a bronze sculpture, titled ‘Bar’, that has been doctored to dispense liquor. The piece is part traditional sculpture, part performance: only complete when the audience themselves get drunk. “The furniture used for the sculpture was part of my childhood,” Wurm explains. “It reflects how I grew up in the ’50s. It’s funny, because now these pieces are considered ‘collectables’.” Wurm’s sculptures question not only the viewing habits of his audiences, but the purchasing habits of collectors. Considering his own collection of artwork and furniture, this is as much self- inquiry as it is a broader societal critique.

The stiff enforcement of a singular point of view concerns Wurm. He describes the current dogma of political correctness as the “new pathos.” Although he admits that “our world is not in the best conditions,” he worries that trends in society’s expectations are “unyielding judgments made by some people about what we must do, and what we cannot do.” For him, rigidity is not only exhausting but dangerous: “Nowadays, you’re not allowed to say certain things; there is control everywhere. Free speech and free thought are fading away. So I ask questions and wonder where is this all going? I understand both sides of the debate but have my doubts that a strict approach to these matters will lead to peace in the end.” In a world that feels more polarized than ever before, Wurm’s attitude is refreshing. His sculptures reflect this ongoing process of interrogation, rather than the passing of judgment.

Inside the storage facility at the Studio, Wurm pulls the plastic covers from his sculptures with a deft tug, pointing out some minor scratches on a fat ‘UFO’ recently returned from Boston. He still remembers the journeys that each of these pieces has made, from their birthplace in Limberg, to exhibitions and museums throughout the world. Despite the size of his empire, he is a perfectionist who understands the value of his work and his brand. “Throughout my 23 year career I’ve only produced 109 ‘One Minute Sculptures’,” he explains, “I could’ve made thousands but this would have minimized and weakened the work; I wanted to be as strict as possible.”

We walk the gravel path toward what Wurm calls the ‘Glass Houses’, which are actually DIY plastic sheds in the distance. ‘Fat House’ has a paddock all to itself, the man-made hill titled ‘The Sleeping Venus’ is its dramatic backdrop. Inside the ‘Glass House’, Wurm becomes animated when describing how he “physically attacked” these more recent pieces inside the ‘Glass House’ with his “full body”, by repeatedly driving over an oversized gun titled ‘Snake’, and doing push-ups on a replica of Japanese wall cabinet. The pieces explore “the concept of sinking into something and leaving a track,” Wurm explains. When asked ‘why push ups’ he clarifies, “I realised it’s an interesting way of creating new things.”

Despite the number of commissions Wurm receives, he admits that he creates practically nothing site specific. “My work all starts in the same place, with me as a person, with my character and its development over the years. The only constant is that I try to look at the world through the lens of a sculptor, and ask questions like, ‘What role might embarrassment play in a sculpture?’, ‘Does the feeling of embarrassment have sculptural qualities?’” Walking back through the Studio’s gardens to Wurm’s office for coffee, we see the grounds are dotted with the artistic manifestations of these questions. Sausage-men appear shy, and cucumbers stand regal. Wurm harnesses emotions for his work in a humane way: by offering participants in his ‘One Minute Sculptures’ a moment to reflect on how they feel in the face of societal pressures; or by casting these moments of friction or discomfort in the recognizable, comforting forms of Austrian food staples.

“When I started out, I made drawings, 3D sculptures, and performative sculptures,” Wurm says of his varied oeuvre. “I didn’t want to restrict myself to one medium, so, depending on the mood, I focused on one aspect of my work more than the others. Sometimes the public was more interested in the ‘One Minute Sculptures’, other times more in the ‘Fat’ series, but it made no difference to my work. I was doing the same thing, continuing to move forward.” What determined the success of certain pieces at certain points in his career? And what drove these trends and his response to them? “Perhaps it’s strange to have worked in different mediums and on different ideas simultaneously, but I adapted to the flux, and somehow it worked out ok for me,” he says.

Wurm strives to deal with the major questions of our lives with levity. He seduces his audience with absurdity and irony, inviting them to join him on a journey. “When I was studying, I realized that the big questions of our lives were treated with ‘pathos’; everything became big and important,” he explains. “Standing in front of these big, heavy works, I felt small, as if I was shrinking,” he says.

Wurm wants the opposite for his audience, and it’s perhaps the reason his work is both approachable and interactive. As a student he was inspired by Picasso, who he felt “was looking at things in a different way; he was playful, he was funny, he was inventive, and he did not follow one style.” Wurm’s own work has also been described in these terms. “It’s not always about following one specific program; my work relates to the character of a person, the character of me as a person. But who knows? Maybe everything is very different,” he says. Despite proving his longevity as a sculptor working across many different mediums, Wurm refuses to be an artist of fixed presumptions.

Wurm is generous with the studio and its grounds, and we are permitted to linger after he drives off to another meeting, the sound of his motor trailing off behind him into silence. Studio Wurm is perhaps one man’s kingdom, but the works in process, in storage, and on display tell the evolutionary story of an artist that is never satisfied with an easy answer.

All images © Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek for IGNANT Production