Chloé Milos Azzopardi On Her Photographs’ Power To Communicate Emotional Depth

- Name

- Chloé Milos Azzopardi

- Words

- Devid Gualandris

French photographer Chloé Milos Azzopardi is not afraid to depict the complexity and psychological depth of the human condition. Centering her work on questions of existence, connection, and otherness, she elicits the interest of the viewer through textured and mystical images. In this interview, she opens up about transcending boundaries and letting her images shape themselves.

Azzopardi has always been an observer, easily awestruck by simple splendor in everything. A fine arts graduate fascinated by the magic of frozen moments, she found her way into photography quite naturally, experimenting with the medium as a source of diversion in her quiet days filled with boredom. Mostly self-trained, the Paris and Catalunya-based photographer creates stunning images that merge views, angles, and scales, with a deep palette of an artist who has mastered her craft. Adding a dream-like quality to her frames through a combination of natural and unexpected elements, she explores forms and shapes found in her surroundings—familiar, but with a sense of distance. Both planned and spontaneous, her shots capture the ephemeral as much as they embrace the accidental, gently revealing the sensitive state that lies beneath the surface of each fleeting moment.

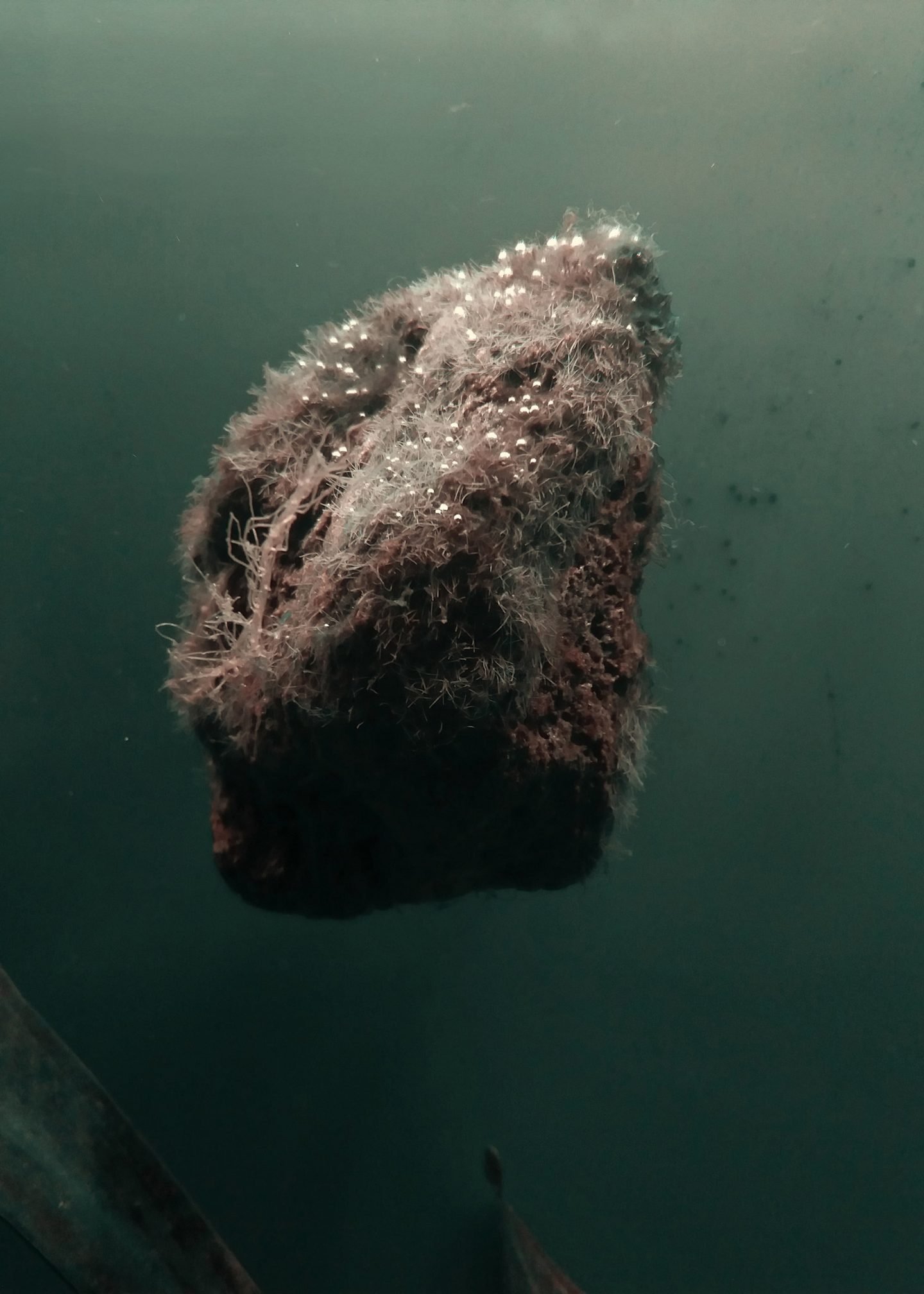

From deconstructing gender to astrophysics and epigenetics, Azzopardi’s themes are wide ranging—and never boring. Driven by a desire to understand the state of her body and mind, her latest, and ongoing, series, ‘Les Formes Qu’illes Habitent en Temps de Crise’ is rooted in her experience of depersonalization—a condition in which one feels extended detachment from their body and thoughts. “The disorder affects my ability to form a constant self,” she explains; “marked by the regular disconnection to my body, loss of feelings and boundaries, I got used to imagining the perception of the surrounding living things; projecting myself in animals, plants, and objects.” Using the images as distractions as well as a tool to redraw the outline of things, Azzopardi explores the relationship between human and non-human beings, as well as ideas of otherness, and the dissolution of boundaries. The result is a highly sensorial and intimate look at a transitional period of her life, one filled with contradictions, ambivalences, and moments of collision but also harmony.

Azzopardi’s incisive eye, sensitivity to nuances and fragilities, and refined aesthetic all make for an incredibly bold and humanistic conceptual storytelling. Below, the photographer reminds us how exceptional art can be modeled from the ruins of our, at times incomprehensible and inescapable, reality.

How would you describe your approach to photography? Would ‘experimental’ be the right word here?

Yes, I think this is what best defines my practice. I never really had a photography mentor—I borrowed cameras from the workshop and learned by observation and making mistakes. Errors and accidents compelled me to discover other ways of making photos. I still work this way today.

Do you feel like you’ve had any sort of personal growth since you started photography? Has it helped you understand yourself?

I don’t know if it was photography that initiated my personal growth, but looking back at some of my photos made me realize how my image-making has changed over time. I had a tendency to favor a very controlled and tight framing, with the subject centered in the image. After a while, I understood the need to isolate the subject. The urge to clearly define its limits was perhaps linked to the fact that my dissociation condition made me lose the sensation of limits in my own body. Now, I try to leave my images more open.

"Errors and accidents compelled me to discover other ways of making photos"

Do you have some sort of set routine around how you’re creating your images? Or is it more that it happens when it happens for you?

I have no routine in photography. Image-making doesn’t require the same rigor as writing. Photography works mostly as an adventure or a wandering through time, place, and emotion for me—one that enables me to explore, connect, and experience. I let myself be carried away while remaining attentive to the multitude, to the microscopic as much as to the macroscopic.

How do you choose your subjects? Or do they choose you?

It works both ways. Having a camera attracts a lot of encounters, whether it be with humans or non-humans. Sometimes I choose them, sometimes they choose me. I approach photography the same way one may the sense of touch—it is impossible to touch without being touched in return. I like to think that when I look at something, I’m looked at in return, even if what surrounds me does not have eyes.

Are there any experiences of shooting you can pinpoint that changed your approach to photography?

It was at the beginning of my photography practice. I was deep in the outskirts of Shanghai, my ankle was badly twisted, and I entered a building in ruins that seemed completely abandoned. On the second floor, I came across a dog. He was terrified, kept barking and trying to jump on me. I ran away. After walking for 30 minutes, thinking about him and the look on his face, I turned around and went back. I sat for a long time, meters from him. He got used to my presence; we looked at each other a lot, and I ended up taking his picture. That day was a turning point for me: I understood that photography can require a lot of patience, desire, leading us to the unknown and to new encounters.

In your work, you question ideas of otherness as well as the separation between human and non-human living forms. Where does this fascination stem from?

I grew up surrounded by animals and animal stories. My grandfather was passionate about birds and plants. When I was four, he was tending to three injured buzzards in his garden, and I would go feed them with him. Before I was born, he also healed penguins—the story goes that he gave them a bath every Sunday. I’ve always had a bond with animals, intrigued by their empathy and their curiosity. Sometimes, back when I was going through depersonalization, by looking into the eyes of an animal and sharing an unidentified emotion—one that we cannot decipher for we use different interpretation grids—I would find my sensations back. Their otherness was in fact very familiar to me. This is why I want my work to invite people to, when faced with the radical otherness of an animal or plant, recognize themselves in this otherness, rather than entering immediately into a relationship of domination with them.

Let’s talk about ‘Les Formes Qu’illes Habitent en Temps de Crise.’ How did you start developing this project? And what did you set it to be?

I started without knowing it. A camera allows you to get closer to things while keeping them at a distance. For me, it was a tool and a shelter—it made me direct my attention to my eyes and the environment around me, and made me forget the difficulty I had with feeling the rest of my body and emotions. It allowed me to continue to exist in the public space when I was going through difficult moments of depersonalization.

Losing some sense of individuality led to a struggle to understand the boundaries of my environment and then to question how we define our identity as human beings. For a long time, Western philosophy has done everything to distinguish humans from animals, to the point that we thought we were outside the sphere of the living. Based on this observation, I explored the relationships between human and non-human beings, trying to escape from a prism of utility or servitude and seeking instead to identify the common forms that cross us.

"I see this series as a futuristic fable, where it’s possible to create links between different species"

How does this specific collection of images reflect the state of dissociation you experienced?

I’m not sure it reflects dissociation; rather, it reflects a way of appropriating that state of being. This series has become a surreal ecosystem in which metamorphoses are possible. A place where bodies can transform and absorb each other. I see this series as a futuristic fable, where it’s possible to create links between different species and reflect on a future where we take care of our vulnerabilities and interdependencies.

With ‘Les Formes Qu’illes Habitent en Temps de Crise,’ what do you want to leave people with?

I would like people to maintain a heightened curiosity about life around them, to observe terrestrial life with the same enthusiasm they would have for discovering life forms on another planet. I would also like them to feel the strangeness and tenderness of the things that surround us. Yet I know that the series can be interpreted in as many ways as there are eyes—that’s certainly the most exciting thing about it.

What makes you feel creatively satisfied?

Sometimes, it’s the rendering of an image that ends up surprising me—I start to look at the same photo for a long time, as if to tame it. Most of the time, though, my pleasure is related to color. I can spend hours looking for the right shade and vibrancy, only to dive in and get giddy. After each new hue discovery, the eye can dive deeper in color, the search becoming infinite.

Does the reception of the work decide the success of it for you, or is the success in the creation?

For me, success—or joy, even—comes when, after a long creative process, I eventually create an image that I feel is the right one; when ideas come together and the work makes sense by itself. A positive reception of a series does not exactly define its success, but rather functions as a powerful support for future projects. It just gives you the strength to keep going.

Finally, what do you think makes a strong image?

When that image becomes an obsession, when you feel the need to return to it over and over, because it resets the way you look at things. Only a few can do that.

Images © Chloé Milos Azzopardi