Inside The Petit Palais Paris: An Encounter With Ugo Rondinone’s Meditation On Nature

- Name

- Ugo Rondinone

- Images

- Devid Gualandris

- Words

- Devid Gualandris

Every work in Ugo Rondinone’s distinctive oeuvre is imbued with emotion—a collection of intriguing ideas, bearing an infinite multitude of meanings exceptionally configured in ever-changing spaces. Regardless of the medium, his art cultivates a sense of wonder in its viewers, tantalizing them through a poetic filter and inviting them to themselves become part of the experience. At the unveiling of his new exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris, coinciding with Paris+ par Art Basel, we had the rare opportunity to witness and listen to his wisdom.

Ugo Rondinone simply does not miss. If there’s one thing that the New York-based artist does best, it’s to always leave one entranced and visually awakened. We are no stranger to his incredible ability to envelop spaces and all who encounter them—we have been staggered by his works’ scale in Venice, just a few months ago. And yet, he never fails to surprise us. Last week was no exception. For his latest exhibition in Europe, Rondinone transformed the grandiose space of the Petit Palais—home to the City of Paris Museum of Fine Arts—into an emotional world for visitors to witness and engage with.

The artist, originally hailing from Switzerland, is an expert in evoking emotion, and has been since starting his poetic and eclectic career decades ago. Excellent at drawing from a young age, he picked up the interest for art on his own, extending his devotion to the contemporary realm by attending art school in Vienna and working in galleries. Today his work is featured in some of those same galleries—and in private and public collections all around the world. His latest exhibition combines the many themes that have shaped his practice over the years, namely nature, culture, and their intimate interconnection—symbols to which he returns time and again, revealing their complexities with every new show. Just like its title, the water is a poem, unwritten by the air, no. the earth is a poem, unwritten by the fire, the exhibition is a complex proposition—at once demanding and introspective—which the artist chose to communicate through different media, intricate symbols, and unique sensorial and spatial experiences.

Ugo Rondinone at the Petit Palais

In his latest exhibition, he reflects on the intimate interconnection between nature and culture—revealing its intricacies through sensorial and spatial experiences

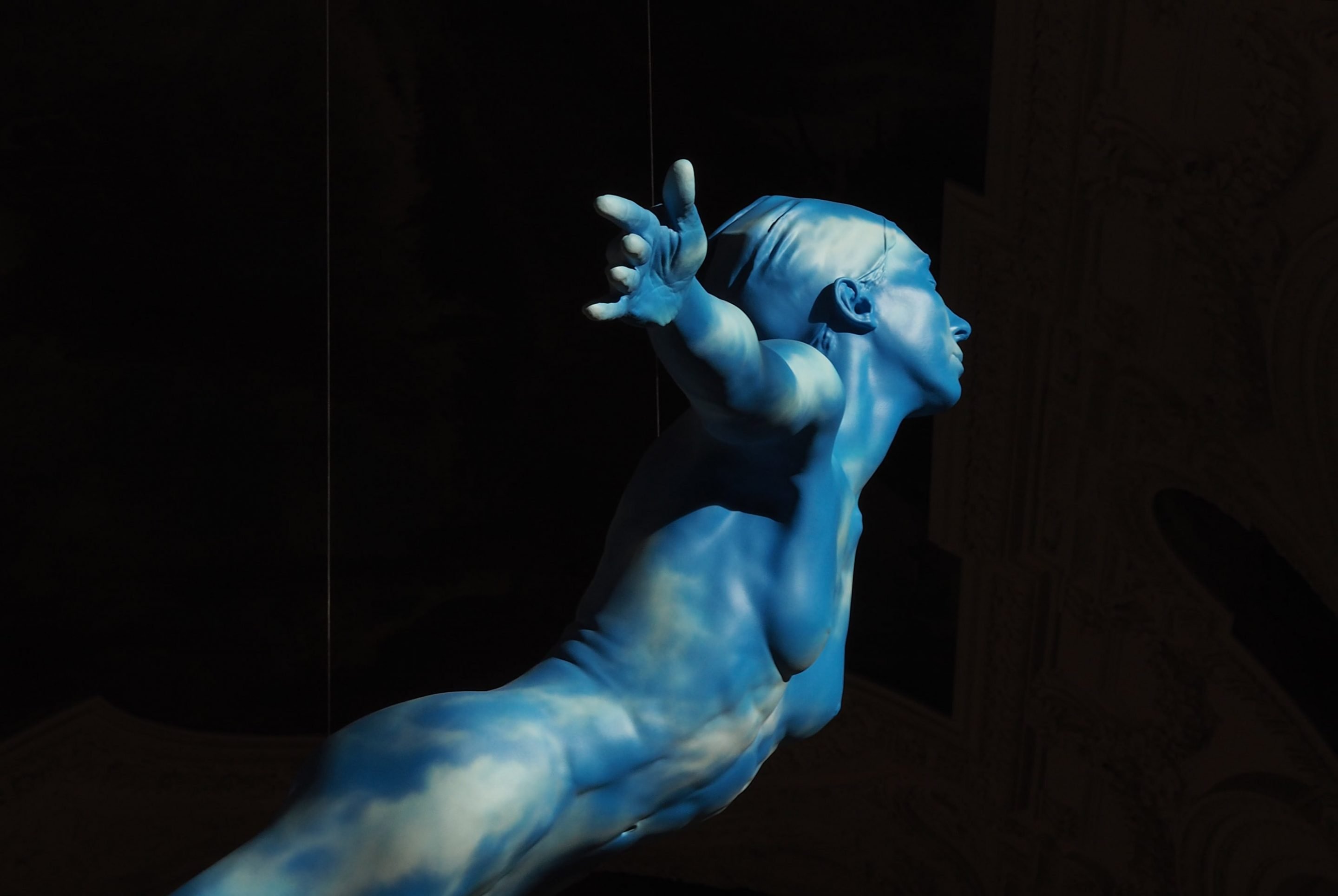

The space of the Petit Palais is a jewel in itself—dazzling and towering, its size immediately forces you to raise your head to see it as a whole. There, hanging in the Rotunda Hall, are Rondinone’s humansky—an ensemble of suspended sculptural nude bodies of trapeze dancers embellished with a blue cloud-dotted sky camouflage. Visitors find themselves instantly captivated, their senses challenged. “The sculptures serve as vessels that contain the natural world of air and water,” says Rondinone, who was inspired for the project by Italian Renaissance paintings. The elemental theme progresses in the Sculpture Gallery with nudes, a series of sitting nudes spread among eighteen historical plaster sculptures from the Palais’s collection. Fragmented and in different brown tonalities, they depict the human-scale bodies of eleven Swiss male and female dancers at rest—self-absorbed and motionless as if in a meditative state. With nudes, Rondinone pushes sculpture to the edge of some avant-garde artistic proposition, raising it above a mere representation of nature. “The sculptures are made of wax and earth, sourced from all seven continents,” he explains. “They merge the element of earth with the human body, becoming one with nature.”

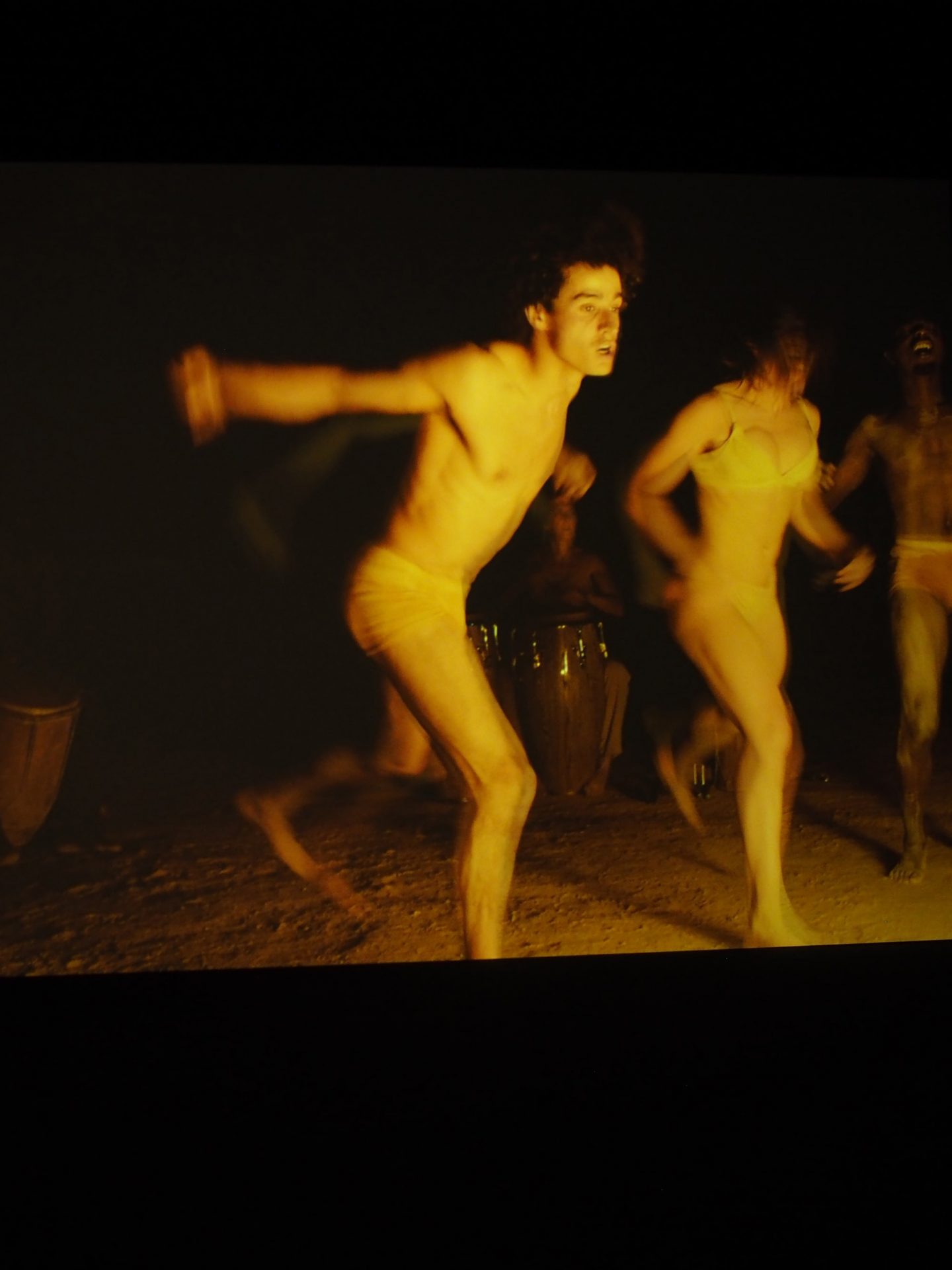

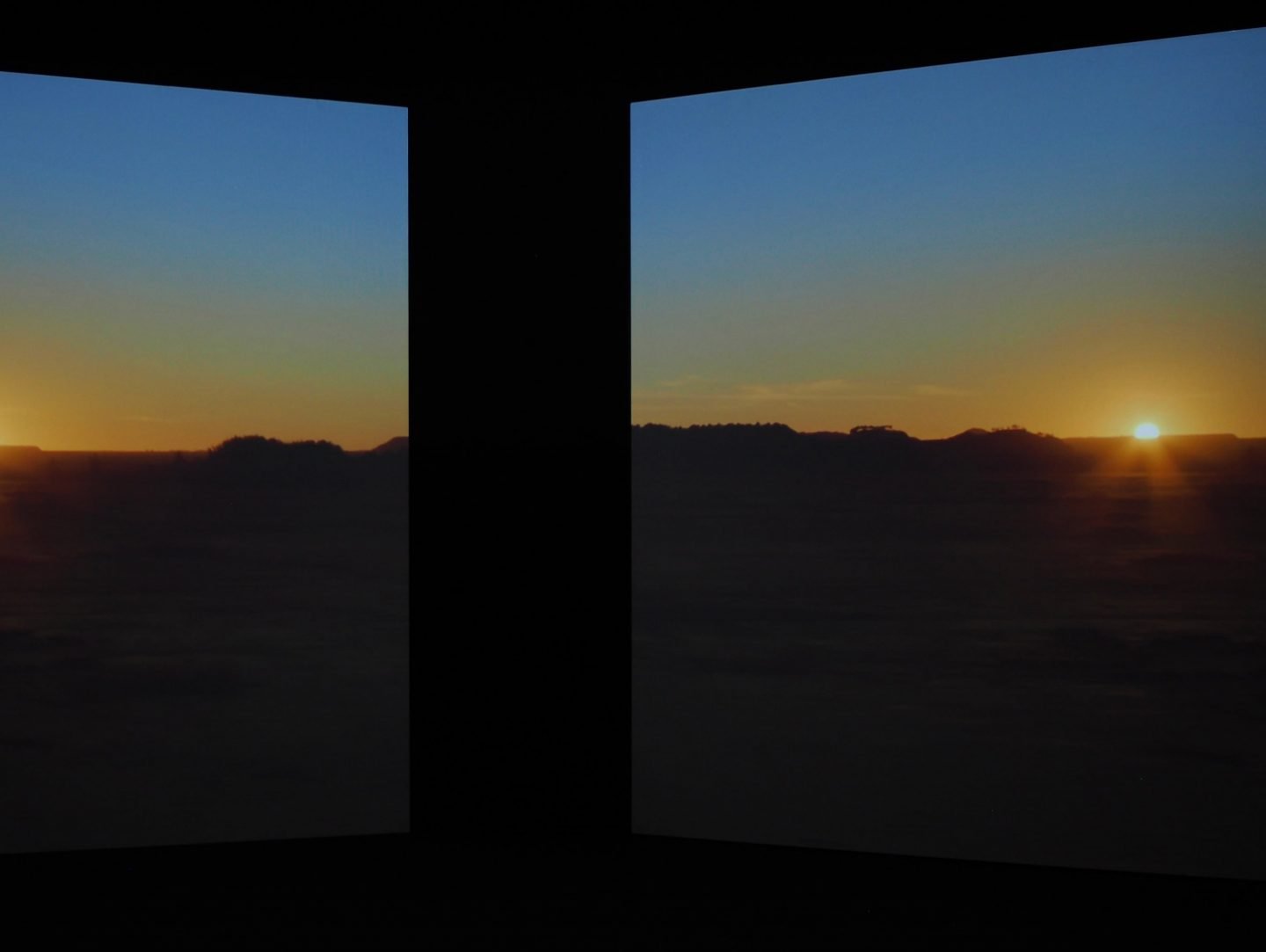

Rondinone’s interest in our collective relationship with the natural world is ever more prominent in the video artwork burn to shine—a world premiere and centerpiece of the show, installed inside a 10-meter-high sculptural cylinder made of charred wooden slats in the North Pavilion. Monumental and visible from afar, the structure has two doorways and is surrounded by four paintings by Eugéne Carrière—“a decision made by the artist,” notes Juliette Singer, chief curator of the Petit Palais. Inside it, an hexagonal room houses six screens projecting a captivating film. The film features 12 drummers and 18 dancers gathered around a fire in an unnamed desert. Performing an ancestral traditional Moroccan trance blended with contemporary dance gestures composed by Franco-Moroccan choreographer Fouad Boussouf, the different human bodies unite with nature from sunset until dawn, taking viewers into a trance state of spiritual liberation. “The initial inspiration for the work comes from a poem by John Giorno, which itself comes from a Buddhist saying describing the coexistence of life and death,” explains Rondinone. “This is similar to the much older Greek myth of the phoenix. According to the legend, a phoenix lived for 500 years. Just before its time was up, the phoenix built a nest and set itself on fire. Then at sunrise, a new phoenix arose from the ashes.”

“The show is conceived of as a trilogy,” Erik Verhagen, curator of the show, explains to IGNANT. “This is the first time the three groups of works have been shown together. It was very important for Ugo that there was a rhythm and narration between the three.” The artist wanted visitors to slowly move from chapter to chapter, their journey culminating in the cylinder—the climax and final discovery of the exhibition. Throughout the Palais, the enthralling feel of the space is underscored by the filtered light and mood set by the palace’s vast glass windows, which have been covered by the artist with gray filters—when the sun goes down and the moon comes up. “It’s an element that many visitors will fail to notice,” Verhagen remarks. “It’s subtle but very present. The filter helps the exhibition to be a work of art, in and of itself. It’s Ugo’s magical touch, to do some discrete intervention that completely changes the space,” he continues—a compelling way to honor the place while transcending it.

To the visitor, the overriding feeling of the exhibition is one of harmony—colors, forms, eras have been combined to tranquil effect. However, “the process was quite challenging,” explains Singer. “We are working with an historical building, which was built for the 1900 Exposition Universelle, and is not fitted for contemporary solutions. We had to take many risks, but we hope that the work of Ugo can be a new way to approach the museum, and help people connect to the four elements and open their minds to new visions,” she says. “The work is like a poem, it can make you discover something in yourself that you were not expecting.” Rondinone is indeed intent on keeping his work open to interpretation—he seeks to encourage his audience to draw their own conclusions based on their experiences and feelings of the moment. Fundamental in this attempt are the principle of the series and the variations of recurring motifs. “The work of Ugo has a kind of circular dimension,” Verhagen explains; “every beginning is an end, and every end is a beginner. He reworks and rethinks points on different levels and perspectives. You always have the impression that you rediscover things you thought you already knew. That’s because they are recontextualized, and every show is different, even if it features the same ingredients.”

Curators Erik Verhagen and Juliette Singer at the Petit Palais

Though he produces shows that become progressively more elusive and intriguing, Rondinone does not see himself as a man of endless ideas. “It’s the work that really dictates the next movement,” he explains. “I only dedicate myself to one project at a time, which fully occupies my attention. I enjoy solitude, withdrawing in the mornings to reflect and nurse ideas and visiting the studios only in the afternoon hours. Solitude allows me to recluse into my own thoughts—that’s when the creative process happens,” he adds. For Rondinone, art is not about mere creativity, it is about openness. “Art is something that enriches your life; something that reads and speaks the way we are thinking,” he says. And while art can question the status quo or provide social commentary, it can also be fun and frivolous.

The artist believes in art as an ordinary element in people’s lives, something that should not be restricted within the walls of a museum. “I’ve always wanted to make art accessible,” he shares. According to him, power lies in familiarity and repetition. Using familiar forms that are instantly recognizable and accessible—such as trees, clouds, the sun, or rainbows—in ever-new contexts and arranged spaces, Rondinone creates new ambiences that trigger the curious mind and encourage interaction. “Art should be an open container. Public sculpture is the easiest and most effective way to reach and engage the public,” he continues. Since 2016, Rondinone’s neon stone totems of seven magic mountains have taken over the barren Nevada Desert. In 2017, Rondinone installed the sun, a monumental radiant bronze sculpture reminiscent of a ring of fire, in the Garden of Versailles, the former residence of Louis XIV. The fascination of these installations has attracted millions of visitors, who are reliably enchanted and captivated by their majesty. “There’s a real desire to have these experiences. It’s important to include people, rather than exclude them,” he concludes.

“A great work of art has the ability to transform the visitor”

Leaving behind the Petit Palais—and Rondinone’s colorful boulder totems just outside it, ready to greets new visitors—one cannot but acknowledge how his art and meditation on nature, whether indoors or out, large or small, can so beautifully initiate dialogues, rearrange thoughts, destabilize perceptions, and even unsettle certaintities. During our visit, Verhagen said that “a great work of art has the ability to transform the visitor.” Needless to say, we are—touched and transformed, at last.

All images © Devid Gualandris