In Conversation With Photographer Mustafah Abdulaziz: On The Arctic And The Interconnectedness Of Our World

- Name

- Mustafah Abdulaziz

- Project

- Arctic

- Words

- Devid Gualandris

Photography possesses the outstanding power to evoke a wide range of emotions within us, transcending time and space—it can communicate stories, stir empathy, and inspire action. Among the many talented photographers featured on IGNANT over the years, one particularly stands out for his thought-provoking work: the Berlin-based Mustafah Abdulaziz. His highly acclaimed ongoing project, ‘Water’, has the rare ability to transport viewers into the heart of the captured moment, stimulating introspection and igniting a sense of connection to the world. We caught up with the artist to discuss the project’s latest chapter, ‘Arctic’, and how his images encourage us to recognize the beauty and complexity of our relationship with Earth.

Propelled by his curiosity and enthusiasm for travels, the Brooklyn-raised photographer Mustafah Abdulaziz has been capturing the wonder of the world around us for over a decade, evoking awe and appreciation in those who behold it. Though disparate and constantly evolving, his visual work has created a cohesive narrative that resonates deeply with viewers, inviting them to pause, reflect, and connect on a deeper level with their surroundings. What is the secret? Abdulaziz’s keen eye for composition and sensitivity to light and color enable him to freeze moments in time, preserving the raw emotions and subtle nuances that distinguish each frame.

His ongoing, long-term project, aptly titled ‘Water’, explores humanity’s relationship with water in a truly remarkable way. The project began in 2011 and is meticulously structured and thoughtfully curated. It is divided into chapters and approached thematically and geographically, with each illuminating different aspects of that relationship. Spanning across disparate regions and cultures—from the arid lands of Somalia to the bustling cities of Pakistan, from the rugged landscapes of Sierra Leone to the mesmerizing Pantanal river basin in Brazil, and the brushlands of California. Moreover, it draws attention to the profound complexities of our collective and individual interactions with it. The series delves beneath the surface of the world’s most vital resource, water, to examine the behavior and experiences of individuals, communities, and nations, providing a comprehensive and multifaceted look at the subject.

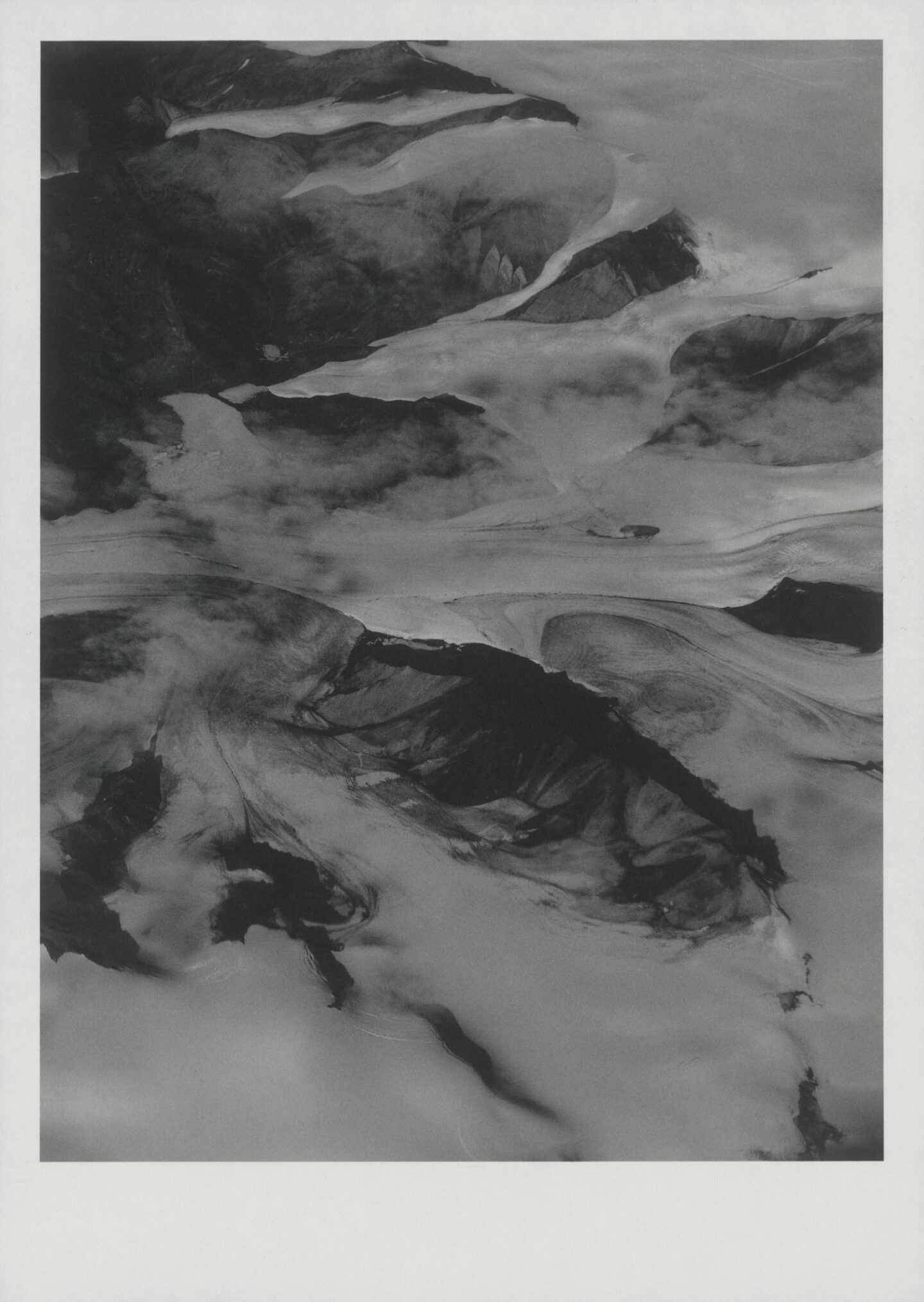

Glaciers. Baffin Bay, Canada, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

'Arctic' reminds us of the inseparability of our well-being from that of our environment

The latest chapter, ‘Arctic’, is a testament to his artistic vision and commitment, capturing human coexistence with the breathtaking nature of the Arctic region. However, the images are more than just pretty pictures; they reflect our behavior, revealing the interconnectedness of our lives with water and reminding us of the inseparability of our well-being from that of our environment. With each frame, Abdulaziz invites us to consider our roles as ‘custodians of the Earth’ by asking larger questions about values and priorities and charting a course toward a more harmonious future. He invites us to not only be inspired by nature’s beauty and magnificence, but to awaken new emotions that will lead to action and bring about positive change.

Below, we discuss the origins of Abdulaziz’s visionary approach and inquisitive spirit, from his early fascination with escapism to his move to Berlin and the new sensibilities and inspirations he found there. Then, we discuss the project’s structure, evolution, blessings and curses, and photography’s transformative power.

Record low summer ice melt. Arctic Ocean, 2022

Let’s go back to the beginning. How did your journey in photography begin? What in particular did you respond to, and why did you feel it was right for you?

I never intended to be a photographer—it wasn’t on my radar growing up and wasn’t present in my education. Where I come from, the options were either a university to study, if you were lucky and could afford it, or straight into a vocational work program that turns into a 9-to-5. Photography, filmmaking, or journalism were dreams—impractical dreams. I had always felt like an outsider growing up, half-black, half-white, with an Arabic name but wasn’t Arab. Before I was aware of it, there were all these boxes around me. I can sum up my childhood as one big confusing mess of feelings—my interests and slightly resistant disposition didn’t align with others my age; my family is big, and my attention deficit issues created a lot of emotional distress. This really defined my sense of independence. It made more sense to lean into self-reliance, and I reckon that’s where observation and critical reasoning helped insulate me from all the things that felt alienating or overwhelming.

The only thing I wanted to do, and maybe still do, is be a pilot. That required joining the military or a vocational school. I was at a crossroads—one path felt like a carrot being dangled, and the other was more ambitious, undefined. It was a lucky break when I came across photography. I was in my late teens, procrastinating at a bookstore, wandering through aisles of books as I pulled down this large white book, Richard Avedon’s magnum opus In The American West. His photographs were a revelation of thought, intention, and execution. It had simply never occurred to me that a photograph could be a mirror, reflecting the feelings and thoughts of the observer. The space between those he observed and himself created this incredibly rich otherness. Ever since, I’ve been fascinated with otherness, which perhaps can be described as atmosphere, essence, or significance. If I felt lost before, Avedon made me feel like I could find where I belonged. There was a rightness to being an outsider. I could go anywhere or anywhere. The only thing that mattered was life itself and the act of being as close to it as I dared. This idea was transformative.

Glacier’s end. Brooks Range, Alaska, USA, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

‘Water’ is now in its 11th year. What compelled you to start this ambitious project?

Research for the project began around the same time I left New York City and quit The Wall Street Journal in 2011. There was something beyond photojournalism I was interested in, where the power of humanistic photography could be applied to contemporary large-scale issues, and the output could create unusual and impactful responses in viewers. There were some things about photography, in general, that were frustrating. It didn’t feel very inclusive of people who were different from the status quo or who came from backgrounds and experiences outside the traditional channels the industry seemed to value at the time. That wasn’t where things were for me, so I went to Berlin and found a vibe that was more in line with who I was and what I valued. Berlin was an open canvas of time and synchronicity. I had been searching for ideas that felt like a gauntlet and challenge. Topics that were most attractive revolved around themes of common experience—energy, migration, population growth, and climate change. The greatest story of our generation won’t be found in war zones or pop entertainment. The question is nothing less than the survival of our species. This felt worth pointing a camera at. It’s an underestimation to say the project is about water. It’s always been about choice and the absurdity of consumption and relentless irresponsibility that has led us to where we’re at now. That’s where the project was born, and that’s the long short of it.

Looking back, would you have done anything different?

Yes, I spent a lot of energy trying to convince people who held keys to things I thought I needed. It turns out I just needed to stop asking permission and go and do the work. It seems pretty logical now to do a project like this, but it wasn’t always this way. The conviction of learning what your own voice is takes a long time. It’s a road paved with difficulty and a lot of failures. But it’s worthwhile.

The remains of a geodesic dome meant to grow vegetables for local consumption. Svalbard, Norway, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

"In order to do the best work, we’ve all gotta come up with strange ways to trick ourselves into seeing things for the first time"

How do you approach a new ‘Water’ chapter? How much planning and research goes into it? And how much of the work is intuitive and spontaneous?

Usually, the next thing comes to me in the middle of the current thing. One thing leads to another, right? As for planning and research, this used to take up the majority of my time. Now I pay more attention to intuition. In order to do the best work, we’ve all gotta come up with strange ways to trick ourselves into seeing things for the first time. In practical terms, I do deep dives into potential chapters before I ever pitch them. Somewhere inside the research, in the late-night conversations with friends and colleagues, is the kernel of the idea. This is followed by rounds of interviews and a reading list compiled from people who live within the scope of the new chapter. Then, I draft pitches while simultaneously looking at unrelated films and books and go into what I like to call a self-imposed exile. Distraction is costly at this stage. It’s also this stage where the chapter either succeeds or fails because I have to analyze my concepts, methods, feelings, and approach. This can last for days or weeks, but at some point, I get tired of myself, or someone tells me to get on with it.

The project requires a lot of traveling. Have you always been a hodophile? What types of travel do you find particularly exciting?

Earlier, you asked if there was anything I’d do differently. I started this project when I was 25. I’m turning 37 next month. What once drew me to photography isn’t the same anymore. Traveling doesn’t mean the same thing. I grew up learning photography through road trips around America. I miss this. There’s no easy way of reconciling a road trip while doing the work I’m doing now. Hopefully, that’ll change one day. The travel I like is more wandering, more languid, and less about travel. I want to drift around the mark, not bullseye it. All the interesting things happen in between.

Blood from a seal butchered by Inuit hunters stains the sea ice. Arctic, Greenland, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

Polluted water at the center of the lead and zinc Red Dog Mine, located in the remote far north of the American Arctic, far from access to the public. Owned by Teck Resources. Alaska, USA, 2022

Many photographers tend to be self-critical. Would you consider yourself so?

Photography is an insecure field. You’re alone a lot. You’ve got self-doubt mixing with constant analysis and critique. On top of that, there are too many photographers in general—too much noise. As a result, people end up tightly wound about what’s supposed to be a beautiful and insightful experience. Too self-involved about perfection, or what others are doing, or whatever. The only thing that’s interesting about a photograph is emotion. Even when the subject matter is difficult, there is an elemental exchange between observation and expression. Fluidity, adaptability, and the capacity for depth of mind and character. Everything about the technique can be learned in photography, but if a photographer lacks depth, then no amount of perfectionism can cover up for the lack of meaning.

There’s this thing I used to do when I was stumped during the post-production phase of the project. I would take A5 work prints of photographs and stuff them in my pocket. I’d go for a long walk. Along the way, I’d do other things. In between, I’d stop and shuffle through the prints. Each time I did, I tossed whatever felt weak—or had too many question marks over it — By the time I got home, I’d have one or two prints I couldn’t stand to let go. Those were the ones that stuck with emotion.

"If a photographer lacks depth, then no amount of perfectionism can cover up for the lack of meaning"

Brooks Range glacier ending in a puddle on a ridge. Alaska, USA, 2022

Let’s talk about the latest chapter of your ongoing documentary project, ‘Arctic.’ When and why did you decide to tackle this region’s issues and intriguing stories?

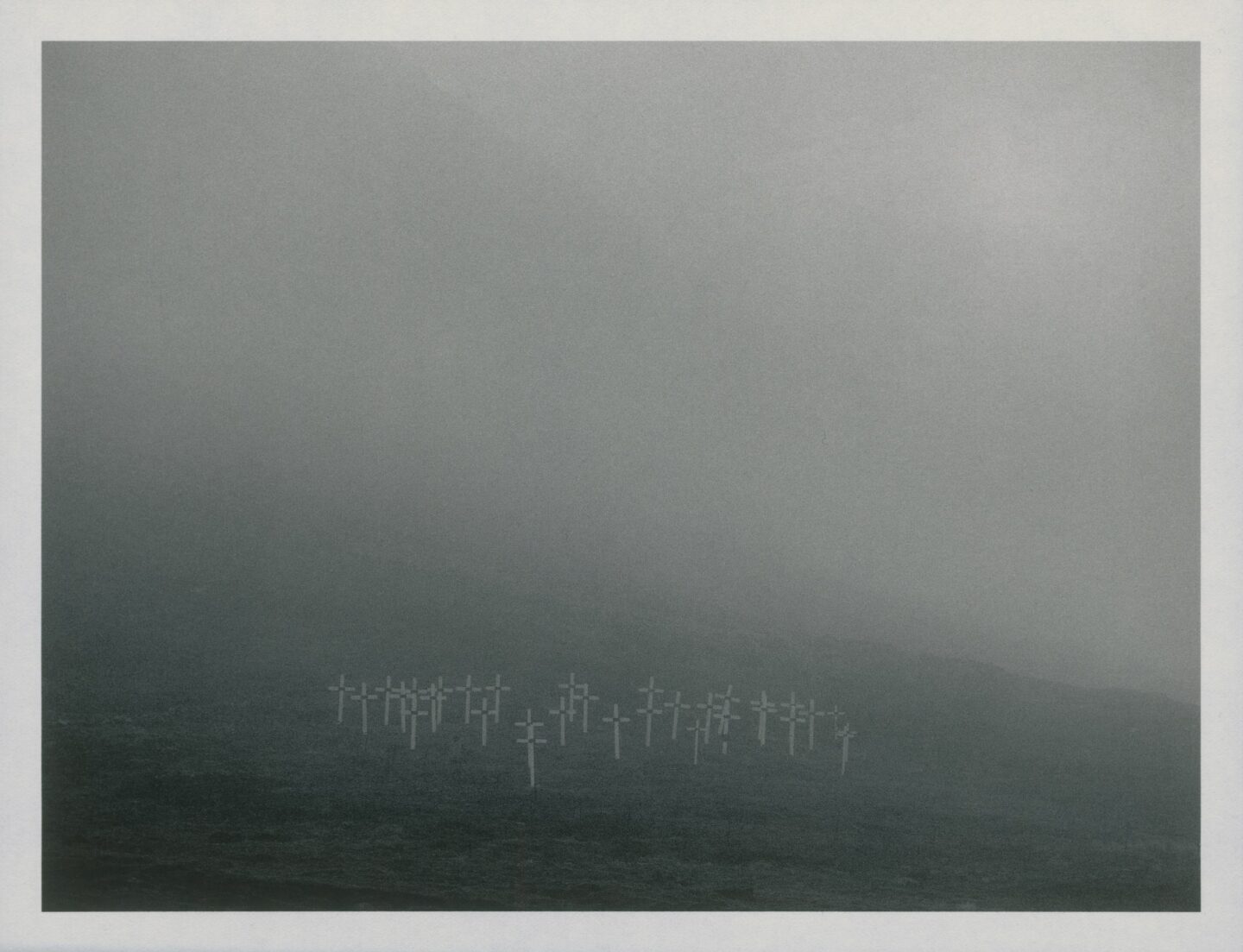

I had wanted to make ‘Arctic’ for a while but hadn’t been ready. I applied for a fellowship with the Bertha Foundation, and their year-long support allowed for the necessary time and space. The Arctic is an incredibly beautiful and vital part of our world; it possesses an elemental, almost primordial feeling. It felt important to weave this emotional essence into the fabric of the new work. I changed my approach entirely. Instead of a single story, ‘Arctic’ needed to be a commentary on a spectrum of human proclivities. It needed to feel, in its texture and atmosphere, like an emotional weight of our planet fading into memory. This is why the final collection of ‘Arctic’ photographs are on Japanese rice paper prints, 21×30 cm, mixing the hardness of the content with the softness of something physical.

What of the Arctic do most people know? It’s fantastical, symbolic even. What it’s not is well-known. The Arctic exists as a grand expanse at the edge of the map of our collective awareness, an abstraction too large, too far away, to grasp. That was something I wanted to play with: a common generalized perspective looking outward at an expanse so bright and white and crucial for our survival yet impossible to lay a simple marker upon. So the photographs needed to be what you see. They needed to show this place in a way it hadn’t been shown before. Their style required sequential dialogue, abstraction of scale, and symbolism in pattern and shape. They needed to be both intimate and alienating. Maybe even confusing.

How does ‘Arctic’ represent the natural development of the project?

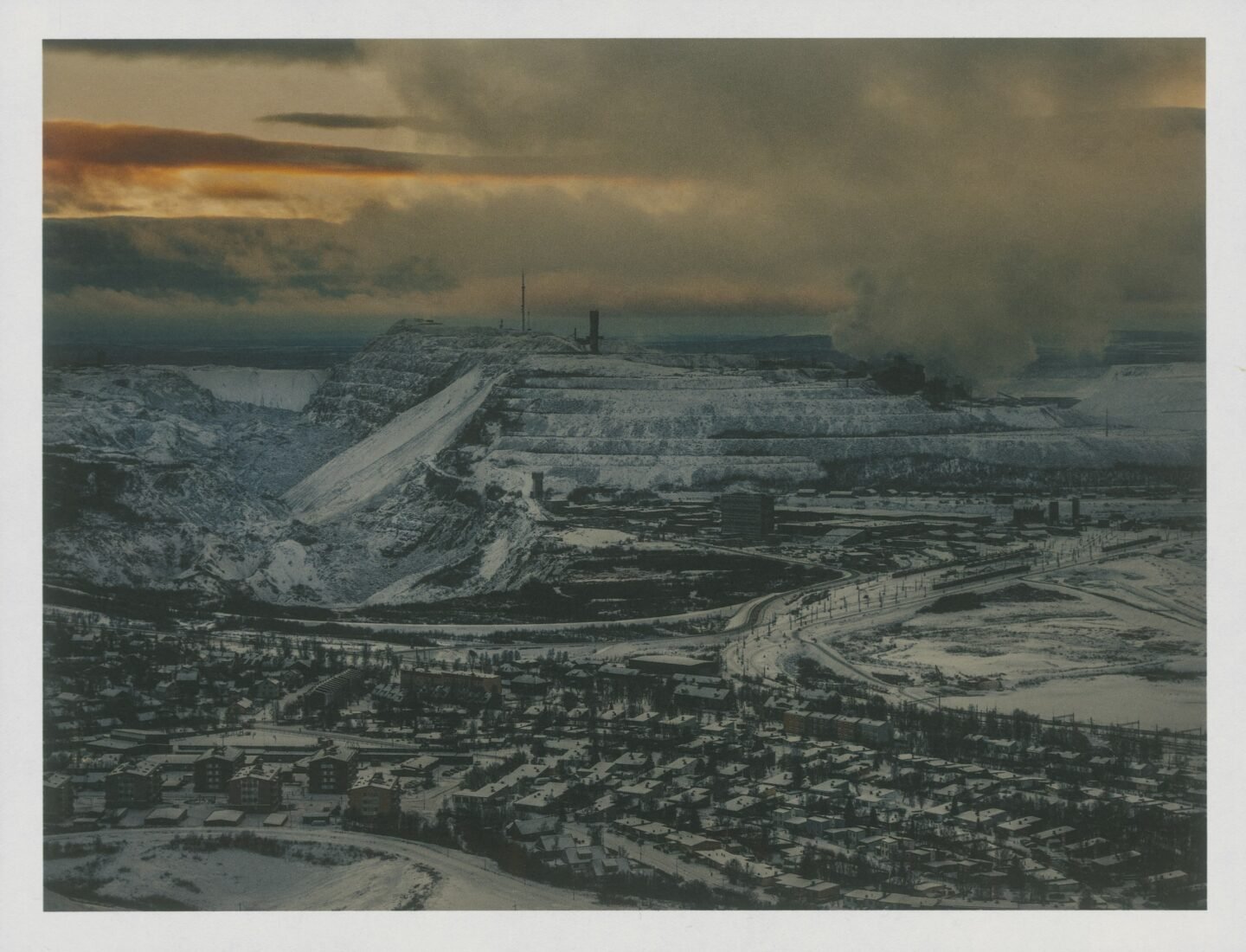

During the first ten years of the project, I believed I was documenting current affairs. What I’m learning now is that the small slices of experience that speak to how human beings are creating catalysts for self-destruction—that’s the real thing I’ve been documenting. There are more interesting stories and far less literal undertones in dialogue about climate change that can be expressed through emotive photographs as critical tableau. I see the first ten years of the work as Part 1. This next part must look backward in history and forward in time to evoke an otherworldly sensitivity to these very abstract places and the significance of our choices.

Graveyard dating to 1918. Any who die on Longyearbyen in is flown to the mainland Over 60% of the population of Svalbard is seasonal and transitory, for mining, shipping, fishing, or eco-tourism. Svalbard, Norway, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

Homes of Greenlanders next to the cemetery. Sisimiut, Greenland, 2022

Heat wave in the Arctic Circle, which is warming much higher than the rest of the world. Svalbard, Norway, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

"'Arctic' evokes an otherworldly sensitivity to these very abstract places and the significance of our choices"

From Sweden and Norway to Greenland and Alaska, ‘Arctic’ has taken you across the world. What caught your attention in the Arctic? Do you recall a moment or conversation you had with someone that has impacted the way you see the world around you?

In northern Alaska, I worked with a pilot named Kirk to fly over the mountains and glaciers of the Brooks Range and up to the Arctic Ocean. Kirk knew the land intimately. He had spent years exploring and getting a handle on his own view of Alaska. Rattling around in his bush plane, I remember having some of the most enjoyable conversations I’d had while working anywhere on the project. We spoke of the nature of the hunters who came to Alaska for their trophy kills and about the history of the state, of the deals and devils who have sought to exploit her valuable resources. We spoke about perspective and storytelling, about the places we’ve seen. Outside the window, the mountain peaks slid by. Storm clouds drifted over ancient glaciers. One time, as we were flying through rain, the treetops were scattered in burnt orange and rough green. We spoke about how to reach people about ideas of preservation and caretaking of the planet—an idea close to both our hearts. It was really special. I remember climbing out of Kirk’s plane and feeling very thankful that I got to have experiences like this. I hope those feelings of gratitude for what wonders this world gives are present in the photographs I make.

Iceberg, Ilulissat Glacier, Greenland, 2022

In Kiruna, located in the Arctic in, workers from the LKAB iron ore mine begin the ski season as iron ore is shipped out along the train tracks at top. Kiruna, Sweden, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

Your photographs reveal the complexities of our behaviors towards the water while reminding us of the urgent need to work towards a harmonious coexistence between nature and humankind. In previous interviews, you have said that, with ‘Water’, you hope to make people sensitive to the issue and mobilize themselves to protect this resource. What do you personally take away from this project?

That was a bit optimistic to hope for. Maybe ten years ago, that idealism made sense. Last year, I saw a movie called ‘Triangle of Sadness’, and towards the end of the film, the social paradigm of the characters stranded on the tropical island shifted comically and tragically in favor of people who hadn’t been empowered in the social structure that led to their boat disaster. When people have the luxury of ignoring the incredible scale of their selfishness, materialism, and apathy, they tend to make some pretty absurd and short-sighted choices. I kind of view the idea of photography mobilizing people to protect this resource, and therefore themselves, kind of like that film’s plot twist.

Water is my subject, sure, but it’s actually the reflector I use to speak about absurd and surreal behaviors. My job isn’t shining a light or bearing witness or any other trite platitudes. It’s not about protecting a resource but ensuring our survival. What I get out of the project is purpose. I take all that anger and sadness at the same things we all witness and do something about it. I’m extraordinarily lucky that what I do reflects my convictions of humanism, equality, and equanimity, of a belief in leaving things better than they were left to us. The act of compassionate observation and humanistic documentation is my way of commenting upon this great tragedy we are all living through and showing that these things are worth fighting for.

Apart from photography, what other sources of happiness do you find?

Dialing into someone’s work process: impassioned craftsmanship. Cinema—Paul Thomas Anderson, Lynne Ramsay, Denis Villeneuve, Claire Denis. Cinematography—Roger Deakins, Emmanuel Lubezki, Greg Fraser, Natasha Braier. Road trips and long train journeys. The coasts of Italy. Byrne v Fischer (New York City, 1956) or Karpov v Kasparov (Moscow, 1985). The mountains of the Midwest. Learning a new way to do something better. Aviation, philosophy. Books, books, books. Late-night dance floors. Music, wine.

The state-owned mining company LKAB has recently discovered the largest deposit of rare earth minerals in Europe, reported January 2023. This will increase mining in Kiruna, which is already moving the city itself in order to access further underneath it. Kiruna, Sweden, 2022 | 21 x 30 cm (edition of 10) | Archival ink on Japanese rice paper 110 / gram

Summer rainstorm over the permafrost. Alaska, USA, 2022

Images © Mustafah Abdulaziz