In Conversation: Christian+Jade on Exploring the Secret Life of Wood with Dinesen

- Name

- Christian + Jade

- Project

- Weight of Wood

- Images

- Claus Troelsgaard

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

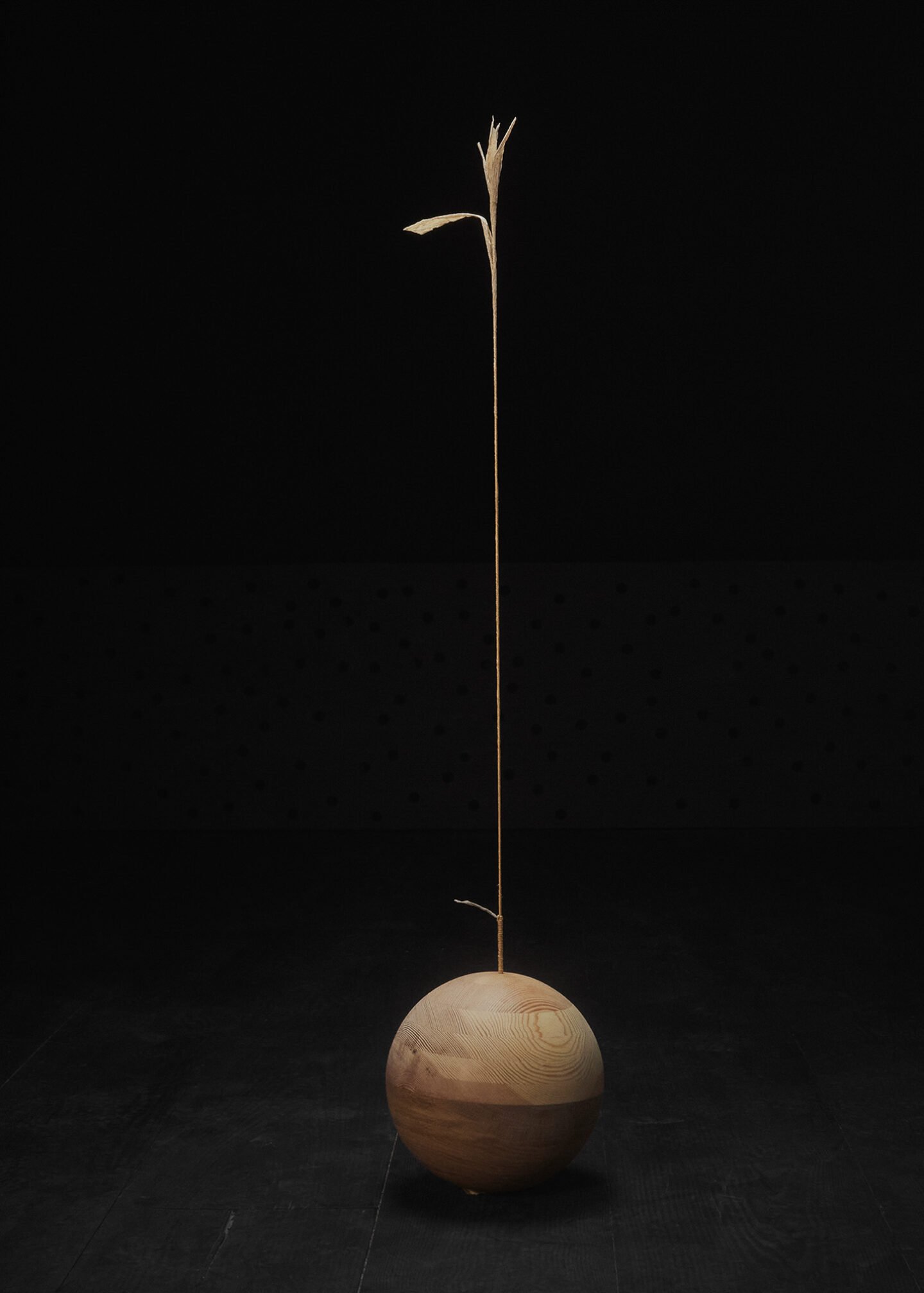

Living organism, raw material, coveted commodity. From the forest through the trees to the floorboards we stand on, wood’s many facets make it a material of inherent tensions. When Christian+Jade, the Copenhagen-based design studio of Christian Hammer Juhl and Jade Chan, began to question why no two pieces of wood weigh the same, they propositioned Dinesen, Denmark’s leading wooden flooring manufacturer, founded in 1898 and today in its fifth generation, to join them in investigating what wood’s density reveals about its personality, environmental conditions, and myriad other properties.

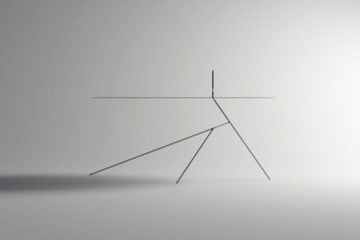

Initial conversations gave way to a month-long residency under the umbrella of Dinesen Lab, the family-run firm’s innovation branch, who provided a carte blanche, open archives, and access to all areas. Christian+Jade interviewed experts involved in every stage of the tree’s life cycle, from wood anatomists to architects and carpenters, and channeled their findings through a highly experimental process from the company’s sawmill in the small town of Jels, South Jutland. Their research has resulted in a highly tactile exhibition at the Dinesen Showroom in Copenhagen, which will run until August 2023. In three sections, Weight of Wood explores the relationship between ‘Forest and Wood’ – an ode to wood in its primary form as a living entity – ‘Wood and Wood’ – showcasing Dinesen’s main species, sourced from Germany’s Black Forest – and ‘Wood and Human’ – centered on three objects that subvert expectations of balance. Jade and Christian took Ignant behind the scenes of their collaboration with Dinsen to reveal what their residency and the resulting exhibition taught them about the secret life of this ubiquitous, beguiling material.

Why the weight of wood?

Jade Chan: As designers, when we’re working with material, we’re always faced with the choice of what to use. It becomes a question not just of what to use because it looks good, but why would we choose a specific wood species over another? That’s how we arrived at wondering why wood has different weights and how we could use that property and that knowledge as a starting point for design.

Christian Hammer Juhl: In the old times, if you were constructing a boat, you’d be using different parts of the tree for different purposes. But today, you mostly use it for aesthetic purposes.

Jade: In the past, you would also go to a forest nearby and use what is available. Nowadays, you have access to everything. There are so many options to choose from. It’s not an obvious choice to use a local wood. So a lot of questions come into play. We came up with the idea of the weight of wood. We had so many plans for it. We wanted to do some experiments. We wanted to research. We wanted to make sculptures. We wanted to make furniture.

To achieve all of that, we thought to ourselves, “We need to contact a company that’s on top of their game, that’s known for having a lot of knowledge around wood, but also who encompasses curiosity. In Denmark, Dinesen is not only known for the highest quality of wooden flooring, but they also have this playfulness. They did a project called ‘A Sense of Dinesen’ [with Sissel Tolass and Pneuma], where they explored the smell of the forest and the trees. When we saw that project, we knew they were the right people to talk to.

From there, how did your residency come to be?

Christian: Very concretely, we created a PDF that became an overview of the project. Dinesen has this part on their website where it says if you have an idea, please reach out. So we forwarded it to their email. Then three weeks later, they responded, “We want to work with you.” We grabbed a cup of coffee with Jens Jacob Dinesen [Head of Strategy and Business Development], who is one of Dinesen’s co-owners, at a café. Then half a year later, the world locked down, and this project got locked down too. So there was a long time between the initial idea and the start of the residency.

Jade: It was sort of a conversation that led to us to decide collectively that a residency was the best format where we’d get the space to focus and really try and explore how we can formulate an understanding of this complex concept around weight and wood.

"Our studio is very focused on how better understanding your materials and objects can change the way you relate to them, the way you understand them, and how you live with them."

When it eventually began, what did the residency look like? How did you spend your days?

Jade: The residency started in South Jutland, where Dinesen has their own sawmill. We arrived only with our idea, not knowing that everything comes into play. We started by talking to the people in the sawmill, people in the production facility. We talked to foresters, scientists, wood anatomists, architects, carpenters – with each of them, we discussed this idea we had about the different weight of wood, and from each of them, we got completely different perspectives on what they thought accounted for the different weights and why.

We started learning that everything affects the weight of wood, as it’s a living material. We couldn’t have perfect conditions in the sense of comparing them objectively. So, what we did was focus on the Schwartzwald (Black Forest) in Germany, where Dinesen gets most of their wood. After speaking to the forester there, we learned that 90% of the forest consists of only 11 species. He shipped all 11 of those pieces to us, and we used that material to start working and making a proof of concept.

The first thing we did was cut each piece of wood into a five-by-five-centimeter block of 250 grams. Right away, we saw that it had different heights. So that was an example of how you could see something as intangible as weight. We didn’t have a full plan for how the residency was going to go, but we came down, we talked, we explored, we reacted to whatever we heard, and we learned.

Christian: We spent lots of time in the workshop trying to create all these small, different objects that would visualize these intangible qualities such as weight – how can we create forms and combine woods in different ways that would balance and just play around with it? That was our achievement – gaining the knowledge and then translating it…

Jade: How can you see it, how can you feel it, and in the end, how can you use it as a design tool? Because the question for us is: How can we bring it back into the home? This knowledge, the stories about the forest ¬– how is that something you can live with? Our studio is very focused on how better understanding your materials and objects can change the way you relate to them, the way you understand them, and how you live with them.

What are some of the prevalent cultural and historical narratives surrounding wood that you wanted to deconstruct as you began exploring these questions?

Jade: One of the very first questions we discussed with Jens Jacob is that weight is always directly related to the concept of quality. We think that a heavier wood is more likely to be of a higher quality, but what exactly does that mean? When you stand up a piece of wood, and someone tells you it’s the highest quality you can get, what constitutes that? That completely matched our starting point from which we could investigate different aspects of the tree. That’s also the story that the sales team at Dinesen explains to clients – this is how it grows, and this is the grain – but weight became a form and a tool with which we could address different connotations. Something that is light, if it’s meant for a specific purpose, could be of a really high quality for that purpose. It really depends on context.

Can you share a specific example of a type of wood that challenges conventional connotations?

Christian: The wood anatomist we interviewed told us about the beech tree and how it’s become this overlooked wood. In the ‘80s, beech was very popular – and the Danish forest consists of so much beech wood – it’s our national tree, but we don’t use it in furniture, we don’t use it in our houses for our tables and our chairs and our floors. It’s out of fashion because we don’t like the color, we don’t like the grain – as it has institutional connotations: sports floors and school furniture. You don’t want to feel like that at home. It’s interesting that we just export all this wood to other countries.

Jade: We learned that, apparently, it’s the tree of the future in its anatomy and how it’s constructed – it’s able to withstand quite changing climates. It’s a very strong, good wood that’s very stable.

Christian: We also met some people around hornbeam, which is sort of seen as a weed. It’s extremely dense, and when you are working with forestry, you’re interested in creating lots of mass – you want trees that grow fast, you want straight stems. So, they cut down the hornbeam early in the stage of forestry to avoid wasting time growing this tree that people don’t use anymore. In the old times, they used to use hornbeam for mechanics and gears in mills. It’s a super dense, beautiful wood that actually doesn’t have much grain structure – it’s very monotone in its expression.

Jade: It was interesting getting to know how our cultural understanding and beliefs and trends can really shape the way trees grow or what constitutes our environment, our forest.

You mentioned the perceived correlation between weight and quality, but what else does measuring the weight of wood reveal about other facets of the material?

Christian: We had to learn about Dendrochronology, a science where you study tree rings, and through those rings, you are able to map the area that the tree has been grown in. You are able to map the environmental changes in our climate that are happening and science where they often use it for shipwrecks and also for example if you find the tools from prehistoric times, you can look at the wood grains and then put them into a larger context of other wood grains and then say, “OK, this tool was created with wood from Latvia, so why is it in Italy?” These grains reveal so much more than just the age of the tree.

Jade: One example that we have in the exhibition is two pieces of pine, almost the exact same species, but they’re 200 grams different. One of them grew in a Danish forest, probably in a lot of sunlight with a lot of good nutrition. As you can see, what makes it much lighter is this thing called ‘early wood,’ which grows much quicker and earlier. The other piece of wood we found in the Austrian Alps, and it grew at a high altitude of around 2000 meters in harsher conditions, in windier conditions, and hence much more slowly. So that’s an example of how the exact same species can work differently, but it’s also about the conditions – how that’s connected to a bigger picture.

"The goal with that is to remind people that it's not just a material to be extracted and processed, but that it's also part of a living ecosystem."

‘Weight of Wood’ aims to fill the gap between perceptions of wood as nature and wood as a commodity. Why is it important to reinforce that connection?

Jade: We often use this example of how Dinesen is known for flooring. When people are looking at choosing specific types of wood for flooring, they base it on aesthetics, on colors – on what they can see, which is just a surface. But there’s just so much beyond it. It’s a natural material. People come in, asking, “Oh, I would like a floor surface that has no knots, that has a grain that’s super even.” They think of wood more as a material that fulfills an aesthetic function.

We heard from the wood production team that there are requests for materials that don’t really match up to the fact that the tree is a living material. That’s what we think is very important – changing the way we choose to consume and use wood, and being forgiving to the material, understanding that maybe it has knots, or it has cracks, and seeing the beauty in that. By being able to draw the bridge between them, we can change how we see wood.

The exhibition has a section that we call ‘Wood and Forest,’ and the goal with that is to remind people that it’s not just a material to be extracted and processed but that it’s also part of a living ecosystem where there are different species within it. Because forest management has changed the environment – sometimes you can find a plot of land with only one species. But that’s not natural. That’s not how a forest grows best. What is best for us as humans is not necessarily best for a tree or a forest or the ecosystem within it. And that’s just why we thought there were a lot of reasons to explore this gap between the two.

How has your exploration prompted you to reconsider your own relationship with the everyday materials that surround us?

Christian: A surprising thing – a poetic thing – about the tree is that a tree is built up around the stem or a core, and the tree can be 300 years old, but from the same organism, you can have a branch that is only three months old, and all of it is connected.

Jade: I think it was the discovery that two pieces of the same tree don’t necessarily weigh the same, but there can be some from the hardwood, and there can be some from the soft wood, and the hardwood is actually the core of the tree, and tree actually grows around this stem of itself that supports new layers of the tree. We found it very poetic in the sense of how we also build up life based on the core of a lot of history. It was our revelation in the sense of how much a tree can also tell us about living organisms or the way things are.

What do you hope visitors to the exhibition will take away?

Jade: We hope everyone will be able to recognize wood as a material for all its richness and complexity, and beauty and be reminded of why we continue to use it today. Then, of course, we have architects, interior designers, and those who work with wood constantly. With them, we could get a bit nerdier and share a different perspective on a material that everyone knows so well. We live with it – it’s in our floors, our walls, our doors. We’re surrounded by it every day. But our relationships to it and understanding of it can be disconnected. Our goal wasn’t only to look at the relationship between the forest and the trees, but with us as humans in the home – knowing about how wood as a material changes the way we relate to it.

Christian: We included Hans-Peter Dinesen’s poem “To those who love the tree,” which speaks about all these people who are working with the tree. I feel like the poem captures how we want to speak to everyone and introduces every aspect of what constitutes the weight of wood.

Jade: …And how everyone can form a different relation to wood and trees, that they can find something in the exhibition that they can relate to, that brings them closer to the tree.

“To those who love the tree, those who may be fighting the tree, the one who plants the tree, the one who fells the tree, the poet who praises the tree, and the one who simply settles with enjoying the tree.”

— H.P. Dinesen, 3rd generation, Træværk

The exhibition ‘Weight of Wood by Dinesen x Christian+Jade’ is on until August 2023 at the Dinesen Showroom at Søtorvet 5, 1371 Copenhagen. Open Tuesday to Friday, 9.00–17.00, and Saturday, 10.00–15.00.

Images © Claus Troelsgaard