On The Cusp Of Her Next Era, Anahita Sadighi Is Redefining The Role Of The Gallerist

- Name

- Anahita Sadighi

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Activist. Cultural trailblazer. Successful entrepreneur. Advocate for underrepresented artists. Berlin’s youngest gallery owner. Since opening her first exhibition space in 2015 at age 26, gallerist, dealer, and collector Anahita Sadighi has been lauded with many labels. Yet in her personal and work life, she elegantly eludes categorisation, preferring to initiate intercultural and interdisciplinary dialogue to create new connections in the spaces between. In doing so, she expands the role of the gallerist beyond its traditional mandate to incorporate a plurality of perspectives, cultures, eras, geographies, and disciplines. Now, in November 2023, the dialectic between her two galleries—Anahita Arts of Asia, focusing on ancient art from across Asian and other non-Western cultures, and Anahita Contemporary, showing international contemporary painting and photography—finds its synthesis in her new namesake gallery in Berlin-Charlottenburg, designed by Gonzalez Haase AAS. In an exclusive interview on the eve of its opening, Sadighi spoke with Ignant about the vision for her next era, making space for multiplicity, and why West Berlin is where it’s at.

"My aspiration is to make underrepresented themes more visible within a contemporary understanding of art and cultural history."

After graduating with an MA in Art and Architecture of the Islamic Middle East at SOAS, University of London, you opened your first gallery, Anahita Arts of Asia in 2015. Aged just 26, you were Berlin’s youngest art dealer at the time. Two years later, you opened Anahita Contemporary. While distinct in focus, each gallery was united in its purpose to increase the visibility of underrepresented topics within art history and the cultural landscape. Now that you’re merging both into a singular gallery under your name, what can we expect from this new era?

With my first gallery, Anahita Arts of Asia, I specialized in antique art, initially with a focus on Asia and countries along the Silk Road. Later, I expanded the remit to incorporate other geographies such as African and South American art. Two years later, I opened my gallery for contemporary art where I show international contemporary positions with a focus on intercultural and interdisciplinary dialogue with a view to bring together different artists from different generations. This combination of these two gallery programs is certainly a unique orientation in Germany.

My aspiration is to make underrepresented themes more visible within a contemporary understanding of art and cultural history. I think that the specific development of my various galleries—each with its different thematic focus and distinct requirements—harbors great transformative potential. The global events of the last few years have strengthened this belief. Ultimately, it’s a very personal journey that I’m on; one I hope to share with others. With my new gallery, I hope to break new ground and shape my work and my commitments—including my role as a gallerist—in a new way, or rather define them in my own way. The coming months and years will see us be involved in a new curatorial approach and exhibitions that are unprecedented in Germany.

I’m interested to hear how you define your role as a gallerist, given that you’ve forged your unique path within a heavily White male-dominated industry.

I see my work as a gallerist as a fusion of theory, scholarship, practice, and my own family history as well as my passion. The curatorial approach of the gallery is ultimately born out of all these elements. Versatility is at the core of my role as a gallerist. Particularly as a woman, and as a gallery owner and creative practitioner—as well as a musician, a pianist, a collector, and a host—I want to embrace this versatility, to draw strength and inspiration from all these areas, and to carry that inspiration forward.

My curatorial work and my engagement with art are strongly influenced by all these elements; all these realities. It’s interesting; the many facets of my role are often confronted with surprise: “Oh, you’re a gallerist, but you also do these other things!” I don’t think one excludes the other. On the contrary, each cross-pollinates the other and makes it more exciting and contemporary. Ultimately, it comes down to opening up new perspectives on the art and culture of non-Western cultures.

"The space between cultures, between geographical locations, between disciplines and media is the place of the future."

What does it mean to you to live and work ‘in-between’—different cultures, disciplines, geographies, eras, practices, and mediums?

Above all, it means embracing these different influences, looking at things from different perspectives, and always being open to new things, especially because I know that there is no one perfect view. To me, it’s really about living this versatility, and that can be applied not only to my work but also to my private life—to my social contacts and my political views. I think the in-between is generally given far too little attention in the cultural landscape, whether in art, film, or theatre. There are so many stories that take place in the space between.

The in-between space is also home for so many people with a migratory background and that we draw a lot of strength and inspiration from it. Understanding the in-between is crucial to developing a personal identity—a sense of self. Yet German culture tends to find it challenging to embrace the in-between, to the extent that many find struggle to fit in here. I’m convinced that the in-between will play an important role in the coming decades and that it will also have a lasting impact on the creative industry. The space between cultures, between geographical locations, between disciplines and media is the place of the future. It has a very transformative energy because it creates something new from existing components.

How does this notion translate to the debut exhibition in your new gallery?

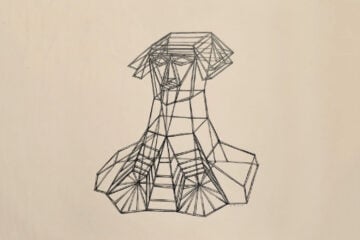

With our first exhibition, What you seek is seeking you, I pay tribute to my origins, and to the special legacy of the way I grew up, with the collection and the work of my father. [Editor’s note: Hamid Sadighi Neiriz is a celebrated artist, gallerist, and collector who for over 30 years directed the Berlin-based Gallery Neiriz, which held a leading collection of non-Western art with an extensive focus on kilims] For this reason, I have decided to show very special works on Japanese rice paper that were created in the ‘90s. During this time, my father was also very strongly influenced by African art, Chinese calligraphy, and Japanese painting. In this respect, the influence of other cultures and the artistic legacy of non-Western cultures is carried on in our family history, a trajectory that I very much wanted to show in the new exhibition.

These works are combined with contemporary sculptures by Dieter Detzner, a Berlin artist whose work engages with ancient Buddhist art, including large bronze sculptures and a special Buddhist deity on a Chinese altar table. We are also showing an incredible Persian nomadic kilim—which is really a museum piece—in dialogue with contemporary paintings on paper. A textile work from the Congo in presented dialogue with antique ceramic pieces, and we’re showing photographs by Kalpesh Lathigra, Yumna Al-Arashi, and a painting on aluminum by Wenxin Zheng. The idea of the opening exhibition was to compile different gallery programs from Anahita Arts of Asia and Anahita Contemporary to present the spectrum of the gallery and to share these dialogues that are strong both in form and in content.

On the subject of your family history, having grown up amongst the art studio and gallery of your father, you’ve spoken about how your parents allowed you to play around and interact with even the most valuable and fragile works in their collection. How did your parents’ approach to art and life influence your own practice?

My family—in particular, my father—have been intensively involved with art throughout my life, and I’ve inherited their passion. Because I was in contact with my father’s collections from an early age, I certainly developed an especially playful approach toward art. It comes naturally to me to combine and integrate works of art in different settings, and artworks also exude a certain sense of security, because they naturally also remind me of my childhood and give me stability and also give me strength, inspiration, and creativity with my work.

It’s true that my parents allowed me to play in my father’s studio and handle the objects there in a playful way, even together with friends, and as a teenager, it was definitely my greatest pleasure to be allowed to engage these objects or somehow use them to inform our own creativity. They didn’t hide their collection, but deliberately shared it with me, and I’m very grateful for that today, because it allowed me to develop this very natural approach to art, and also to antiques. I believe that of course, this natural and very organic approach to living with art is something worth cultivating because it holds so much promise. Art allows us to cultivate a life for ourselves—a contemporary one. Rather than distinguishing between art and life, I want to encourage an understanding of art as part of life’s reality.

I’d like to pause on the topic of personal connections. Growing up as a child of the Iranian diaspora – having been born in Tehran and moving to Berlin as a one-year-old, you’ve described your associations with Iranian culture as “a mythical awareness and melancholy”. Can you elaborate on these two elements?

Iranian culture has had a strong influence on me and has always fascinated me, just like the history and artists of this country. From an early age, I grew up with these mythical, fantastic stories like the Shahnama by Firdausi, (the Persian Book of Kings), and I identified very strongly with them. They greatly impacted my thirst for adventure, my creativity, my willingness to take risks, my passion, and, of course, also my melancholy.

The history of Iran reads like a thriller. The fact that this country was ruled for many centuries by non-Iranian dynasties and at the same time preserved its very own cultural and artistic identity, and even influenced these foreign rulers, moves me again and again. The protest movement ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ [Editor’s note: This protest movement arose in 2022 and Iran and spread globally in response to the death of Jina Mahsa Amini, who died in custody for having been deemed by Iranian authorities to have failed to properly covered her hair] still shows that this spirit still persists in large parts of the population. Iran is a large source of my inspiration and creativity and also of my longing, hence this mythical and melancholic aspect.

In November 2022, you contributed to Woman, Life, Freedom with your installation of the same name as part of the Berlin Design & Art Festival at Stilwerk. Might we be seeing more of your work out in the world?

You can definitely view this work in connection with the question of redefining the role of the gallery owner and not being stuck in one category. For me, this protest movement was a very emotional moment—almost a wake-up call—and it was clear that I had to position myself very strongly and clearly. I wanted to react to it through a generous artistic response, and in doing so contribute to the discourse to draw attention to this movement, and at the same time to my own practice as a curator and gallerist. That’s what led me to the selection of ancient Persian amphorae: these wonderful, versatile ceramics also symbolize this diverse protest movement. I think this work with ancient artifacts or with objects from different cultures can certainly serve to draw attention to contemporary events. For me, it’s about political storytelling—not through the creation of new media, but with the help of old works of art and objects that also have a functional character. This fascinates me, and I imagine that I’ll continue to work in this way over the coming years.

I’m interested in your perspective on the relationship between art and architecture. The spatial concept for Anahita Sadighi emerged over the course of a close collaboration with Pierre Jorge Gonzalez of Berlin practice Gonzalez Haase AAS. What kind of experience did you want to create, and how did your partnership unfold?

I think that art and architecture have always belonged together—that goes as much for ancient epochs as it does today. I had the great pleasure of working with Pierre Jorge on the interior design for the gallery. His vision of combining the old with the new impressed me, and it fits very well with my work. He’s a great artist and visionary. It’s important to him to somehow convey the personality of the people behind a space. He didn’t just design the rooms, he also designed the entire interior, all the furniture design and the table in the office is a real work of art. New stories will be created and told here. We’re also planning joint long-term projects that will see gallerists and architects come together. I truly believe that this kind of long-term collaboration always has this transformative potential and a lasting impact on the work of everyone involved.

Both your gallery and your home are located near Savignyplatz in Berlin-Charlottenburg—decades ago the undisputed epicenter of Berlin’s bohemian art and culture scene, yet a neighborhood that has perhaps over the past decades taken a backseat to other gallery hubs like Kreuzberg and Mitte. Over the past few years, however, several sparks of art and cultural initiatives appear to be illuminating Charlottenburg again. Are we in the midst of a West Berlin renaissance?

The West has definitely been enjoying a revival for several years now, and it’s far from over, which makes me very happy. Charlottenburg has always been an important gallery district, with all the antiquarian bookshops, old cinemas, and long-established shops that characterize the neighborhood around Savignyplatz especially. Then we have the Schaubühne Theater, the Deutsche Oper (German Opera), and the UDK (University of the Arts). There’s just a great foundation here that’s wonderful to work with as a creative practitioner. I’m equally looking forward to everything that is still to come. Many visitors to Berlin appear to be experiencing Charlottenburg in a positive light, while Berliners are rediscovering it for themselves. That’s the nice thing—this district is able to reinvent itself. Of course, as a Charlottenburg resident, I’m also trying to do my bit towards that.

"As an institution or simply as cultural professionals, we have a responsibility to engage in this exchange and to try to bring society closer together again."

One of the ways you’re doing this is through your open invitation to the community to engage with the work you show—and with each other—through a program of events, talks, screenings, and readings that will continue to complement your exhibitions. Can you preview what we can expect here?

We will definitely be launching an extensive program. I think that the disciplines of art and art history, music, literature, performance, and dance should be thought of all together. I consider it essential to my role as a cultural practitioner to present various disciplines in dialogue with one another, and through that, to bring different communities together who can ultimately participate in a dialogue, whether an interdisciplinary or an intercultural one. I believe we’re experiencing a phase of social regression. There is so much suffering, so much war at the moment. The world is on fire and exclusionary and hateful policies are once again being successfully implemented in Germany.

Alongside that, we’re seeing the regression in our ability to discuss and debate issues in a truly rational way. This applies to politicians as well as social networks and even among friends. You’re either in favor or against, either friend or foe. There’s no room for the in-between. We’re moving further and further apart from each other, and it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find consensus. Yet what matters in our society is mutual respect, understanding, and acceptance. These are the ends to which diversity and plurality can be engaged. As an institution or simply as cultural professionals, we have a responsibility to engage in this exchange and to try to bring society closer together again. This is what I want my work to contribute to.

Images © Clemens Poloczek | Text: Anna Dorothea Ker