Deep In The Balinese Jungle, TianTaru Preserves The Lost Art Of Indigo Dyeing

- Name

- TianTaru

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Prized since ancient times for its alluring hue and medicinal properties, indigo holds an illustrious history of textile coloration and enhancement across Asian, Africa and South America—from Tutankhamen’s burial linens to the garments Samurai wore under their armor. Today, its use as a pure natural dye has become a rarity; its methods industrialized; its recipes forgotten.

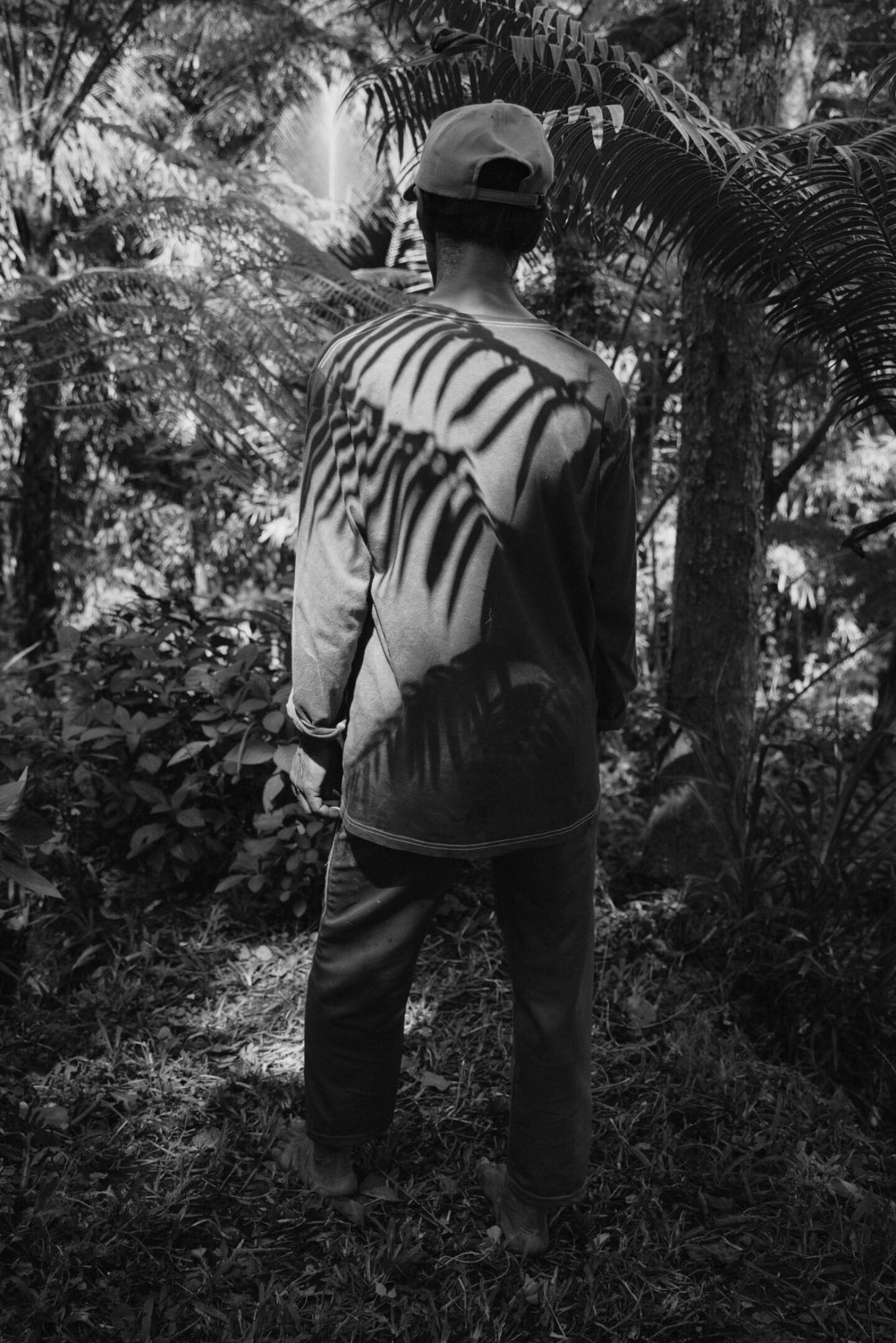

Amidst central Bali’s abundant jungle, a young family have dedicated themselves to cultivating indigo and preserving its natural dyeing methods. Under the banner of TianTaru, which denotes “the tree that grows between heaven and earth”, textile designer and artist Sebastian Mesdag, his wife Ayu Purpa and their small team of indigo farmers welcome artists and curious travelers into their sanctuary. There, among sun-dappled treetops, they can unfurl from the haste of modern life and reconnect with themselves and the natural world through communal craft and ceremony. What they come away with extends beyond an artwork—and stained blue hands—to another way of seeing things, shared generously in reverence for nature’s possibilities.

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

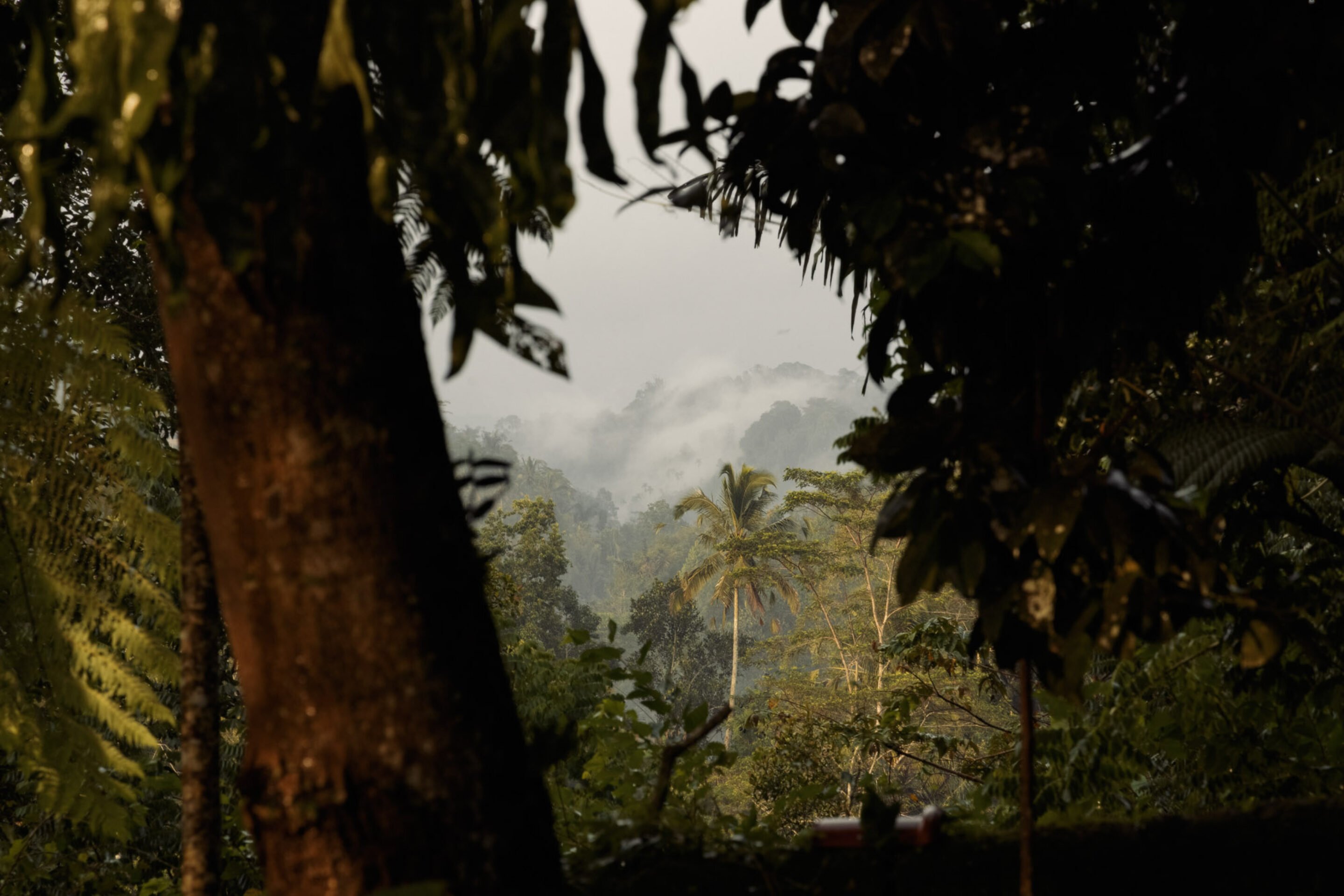

Around an hour north of Ubud, Bali, the crest of an undulating gravel road gives way to a forest draped across several terraces. Horses await patiently at a gate, while a peacock meanders down the driveway, leading the eye to a constellation of native trees that form a forest so verdant it conceals the waterfalls that naturally irrigate it. As beautiful as it is in its own right, this forest was cultivated to serve a higher purpose: a protective canopy of shade and protection for Assam indigo. The forest’s verdancy belies its relative youth. Only fifteen years ago, the land it envelops looked vastly different. An arid field destined to become a rice plantation, it was treeless and devoid of electricity or running water, threaded to civilization via a gritty dirt road. It was this seclusion and consequent tranquility ensured by the challenges of this terrain that charmed the couple as they searched for a land to build themselves a home on.

Mesdag met Purpa during a visit to her native Ubud. Born in southern Spain to Dutch globetrotting parents who instilled in him a passion for travel and cultural exchange, he put down roots in Bali in 2004. Decades earlier, his first trip to Bali was taken at 14 to see the home his uncle, Hans van Praag, had built in his later years, having resided in Bali in the ‘30s when Indonesia was under Dutch rule. It was van Praag who ignited his interest in indigo, by showing him a ceremonial textile headband handwoven from cotton on the island of Sumba. The cloth and its coloring left an impression on Mesdag so profound that it would chart the course of his work and life. He went on to study fine arts at Central St Martins in London and Parsons Paris. Eschewing the chemical-laden paint that dominated the Western palette, his pursuit for natural materials took him to India, where he spent four years living amongst the Santali tribe, with whom he helped set up an embroidery studio that employed 80 women whose shawls took a painstaking eight months to make. In parallel, he immersed himself in the fundamentals of natural dying at Weavers Studio in Calcutta.

In the mid-2000s, as Mesdag and Purpa embarked on the process of constructing the home they now live in with their two children, they took inspiration from Japanese minimalism to design a two-story dwelling open to the elements, complete with an open-air kitchen and a façade-free upper floor. Having sourced recycled teak and ironwood from dismantled houses on Java, they undertook construction fully by hand, without the use of machines or electricity, with support from a representative of each of the fifteen families in their village.

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

“The beautiful thing about Bali is that when you plant a tree, you know that in 20 years, it'll be about this big. You can create your dream in this lifetime.”

In the early days of the process, a friend brought them three cuttings of Indigo. “We kind of forgot about them,” laughs Purpa. “One day, we came to check it and suddenly, it had grown. We had an expert come and check, and when they validated it, were like, “OK, we’re going to do this now.” While the heavy rainfall in the area suited the Assam indigo plant perfectly, it lacked uninterrupted shade to grow. At the time, Mesdag and Purpa were making and selling naturally dyed T-shirts. They poured the profits of each T-shirt into planting a native tree, from unfurling ferns to Bodhi trees to a bonsai that would evolve into a Banyan.

By the time their house was finished, seven years later, a forest had sprung up to create an ideal ecosystem for their indigo plantation to thrive. Thanks to the site’s natural irrigation system of waterfalls flowing into a duo of dovetailing streams, the forest was fully self-sustaining, needing no extra irrigation or intervention beyond the plant’s harvest. “The beautiful thing about Bali is that when you plant a tree, you know that in 20 years, it’ll be about this big,” says Mesdag. “You can create your dream in this lifetime.”

That dream is now shared through TianTaru’s workshops, which are highly personal, hands-on, and primarily an exercise in patience. Uncompromising in their refusal to cut corners, Mesdag and Purpa understand that indigo dyeing is a process that can’t be rushed. As individuals or in groups of two, guests are invited to experience its rhythms for themselves by following the entire indigo lifecycle.

“We start off with the harvest, then we teach our guests how to extract the dye and make the Indigo paste. Then we teach them how to make an indigo vat using only sugar and limestone. So we give them the recipe, then we give them a cloth to dye,” explains Mesdag. They’re also invited to bring a personal item to dye too, in an opportunity to give a new life to an old garment. “We teach them how to do the finishing, and we give them a plant.”

Over the course of two or more days, guests become part of the family, sharing meals prepared from fresh herbs and coconuts harvested from the garden. At night, they sleep on a futon in the open-air guest house that doubles as a yoga studio and a sorting room for freshly harvested indigo leaves. As custodians of a fading art form, transparency is central to TianTaru’s philosophy. “We share all the information we have; we don’t keep anything to ourselves. Our idea is that people can go home and they can create their own studio,” says Mesdag. “Previously, indigo was a secret. No-one would share their recipe, because it’s your trade, and if you show the neighbor, then you lose your custom. Now, we’re getting to the point where we need to share information. Though even if I give you all my information, it’s not going to be the same. Maybe your earth is different. Depending on where you are, the climate—everything—will change your vat.”

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

Images © Pempki

“Indigo's alive, so every batch you make might be a little bit different. There’s red in it, and purple. It's not just a flat color. The darker you go, the more these colors will come out.”

While TianTaru’s dye recipe comes from Malian indigo doyen Aboubakar Fofana, Mesdag and Purpa are quick to underscore its central element of chance. “Indigo’s alive, so every batch you make might be a little bit different. Even when you make three vats the same day, one might be dark, and one might be lighter,” notes Mesdag. “It’s quite sensitive.” Water temperature, humidity and the human touch on the cloth all further impact the final result—as do the number of dips in the indigo vat. Four to five per day are standard, accounting for plenty of time for oxidization. “Indigo isn’t just a flat color. There’s red in it, and purple,” he adds. “Depending on the light, on some materials you’ll see it more than on others. The darker you go, the more these colors will come out.”

There’s equal variation in both the materials and objects dyed at TianTaru. String and wood alongside paper; even entire rooms of houses have been imbued with the deeply resonant blue. Inviting indigo experts and textile designers to stay with them, exchange knowledge, and create together is integral to TianTaru’s ethos. “Every time people bring a different material, we have to think of a new way of dyeing,” notes Purpa. Through collaboration and exchange with the likes of Spanish painter and sculptor Cesar Fernandez, Naruse Kiyoshi of Greenman Banana Paper Studio, Indonesian furniture designer Eva Natasa, and Balinese architectural design studio Blanco—to name a few—techniques expand, refine and feed back into the curriculum. Recently, that has included experimenting with replacing limestone with lye water in the vat, per Japanese tradition, or creating paper from the bark hand-peeled from the trunk of the indigo plant.

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Images © Zissou

Artists return for residencies, teach their own workshops, invite Mesdag and Purpa to their corner of the world. A recent trip to Bhutan, where the Assam indigo plant is believed to have originated from, and where it still grows wild, has inspired Mesdag to refine a recipe only using materials sourced from their land. At TianTaru, the philosophical is inextricable from the practical. “Sometimes people ask me, ‘What happens if the color runs?’ or ‘Will the color fade?’” Mesdag notes. “The thing is, chemicals fade. Everything fades. We always think that everything has to be permanent. But nothing is permanent. In the Balinese language, there’s no word for art. People create beautiful things for the gods, spend hours on ceremonies, then they get destroyed, swept away. Art is for yourself. If someone wants to buy the end result, fine. If they don’t, it’s still your own process.”

Images © Pempki & Zissou | Text: Anna Dorothea Ker