At The Berlinische Galerie, Explore The Experimental Forming Of Sculptor Hans Uhlmann

- Name

- Berlinische Galerie

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

A new exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie sheds light on the oeuvre of Hans Uhlmann, one of Germany’s foremost, yet forgotten, sculptors of modernity, whose large-scale public works engage in dialogue with Berlin’s modern architectural icons. Across seven chapters, the exhibition retraces the forgotten luminary’s life and work, from his formative ‘wire sculpture’ typology to the indelible imprint his public sculptures have left on western Berlin’s urban fabric.

When walking past the modernist monolith housing the Deutsche Oper Berlin on Bismarckstraße in Berlin-Charlottenburg, the attentive eye might be drawn to a sculpture that punctuates the building’s blocky presence. Monumental yet mobile, its folded bird-like form sweeps toward the sky, towering over the low-slung opera house in an evocative image of upward motion. It was commissioned by the building’s architect, Fritz Bornemann, to provide a “sculptural architectural counterweight” to the 64 x 16-meter façade of the cultural institution he would construct in 1961 to replace the site’s original opera house, which had been destroyed during World War II.

In 1955, Bornemann issued a call for entries, marking the first major competition of West Berlin art in dialogue with architecture. Four local sculptors, Karl Hartung, Bernhard Heiliger, Erich Reuter, and Hans Uhlmann, submitted proposals. While the competition called for relief, it was Uhlmann’s design, the sole freestanding work, that captured Bornemann’s imagination. “The widely visible, informal work of art made of black-tinted chrome-nickel steel with polished edges brings rhythm to the uniform surface and accentuates the rather restrained building,” noted an exposé by the German Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning. “With its soaring form, the sculpture creates a dynamic contrast to the static facade, and asserts its effect at night when the spotlights create different shadows.”

Image © Ewald Gnilka

Image © Elsa Thiemann

Image © Ewald Gnilka

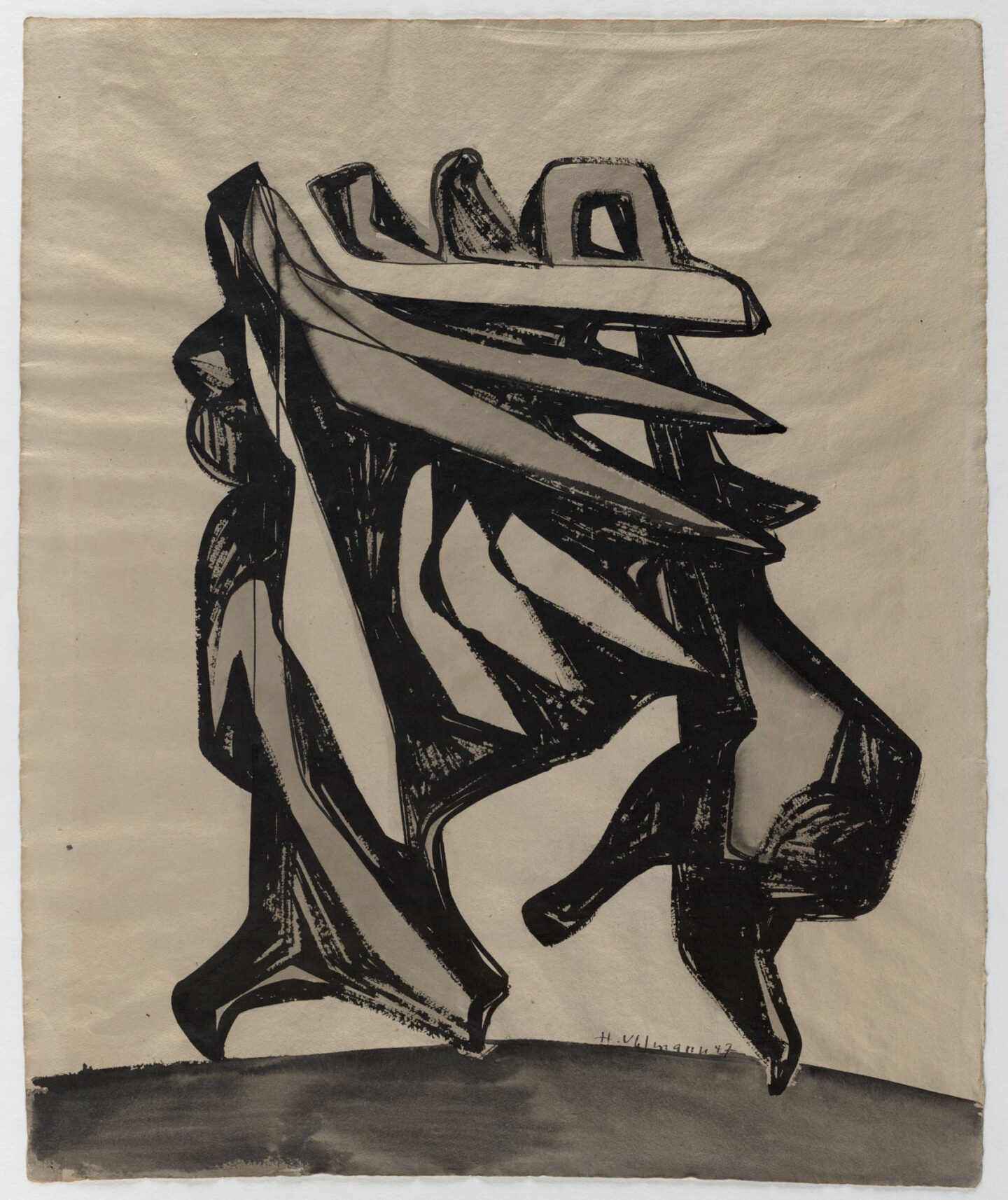

Known affectionately as the ‘shashlik skewer’ today, it is only one of seventeen public sculptures, over 250 sculptures, and countless drawings that comprise the oeuvre of Hans Uhlmann. A luminary of West Berlin modernity and one of Germany’s foremost metal sculptors, Uhlmann has in recent decades remained in the farther corners of public memory. Now, the Berlinische Galerie has turned a spotlight back onto his legacy. The exhibition Hans Uhlmann: Experimental Forming (through until May 143, 2024) deconstructs Uhlmann’s oeuvre from the 1930s to the 1970s. A sequence of seven chapters traces the evolution of his practice. ‘Spaces Shaped with Wire,’ ‘Dance and Movement,’ ‘Transcending the Material,’ and ‘A New Astronomy of Space’ chart his various artistic phases, while ‘Curator and Networker,’ ‘International Success,’ and ‘Monumental Sculptures’ explore Uhlmann’s international success, curatorial work and creator of noted ‘percent for art’ (public commission) artworks.

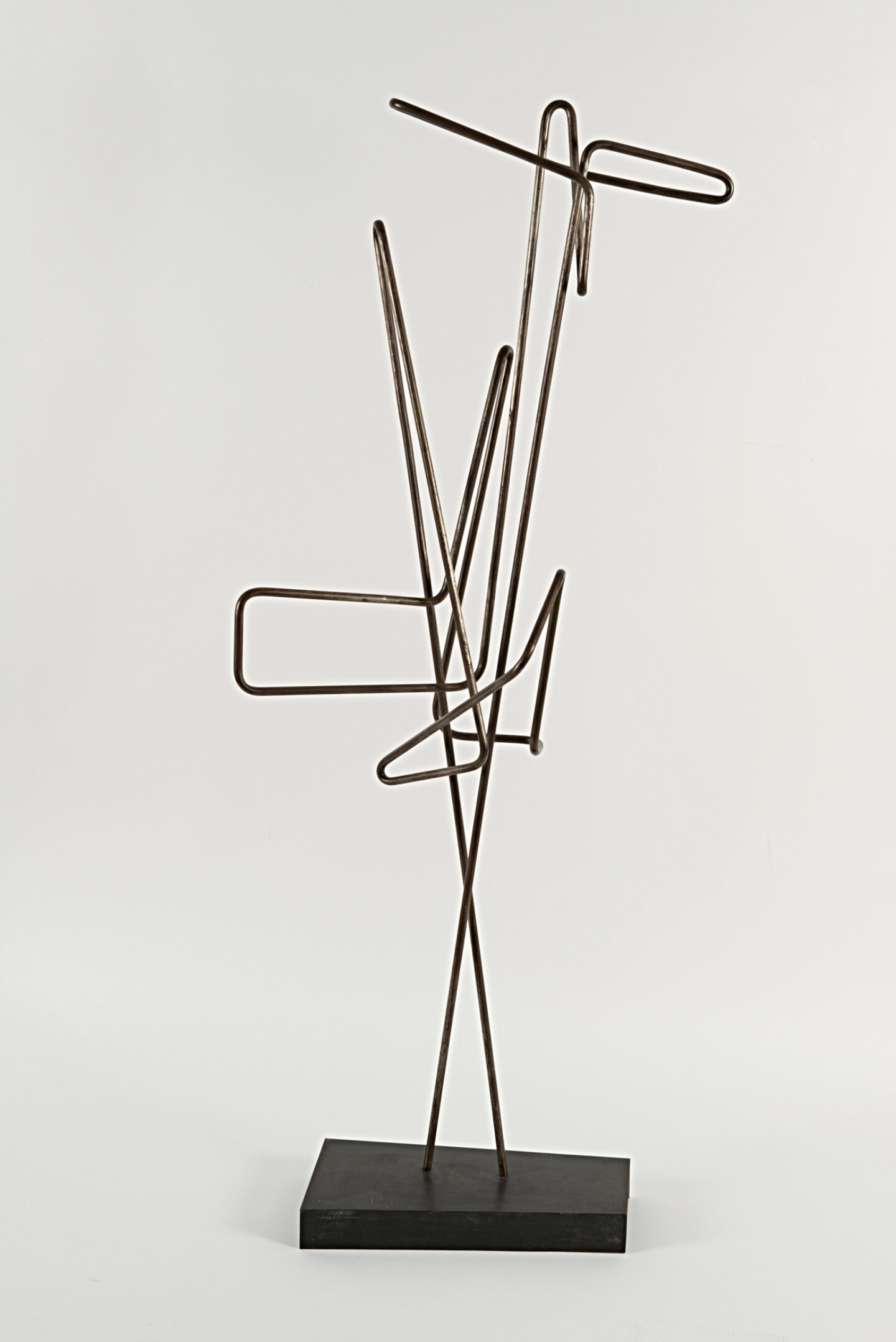

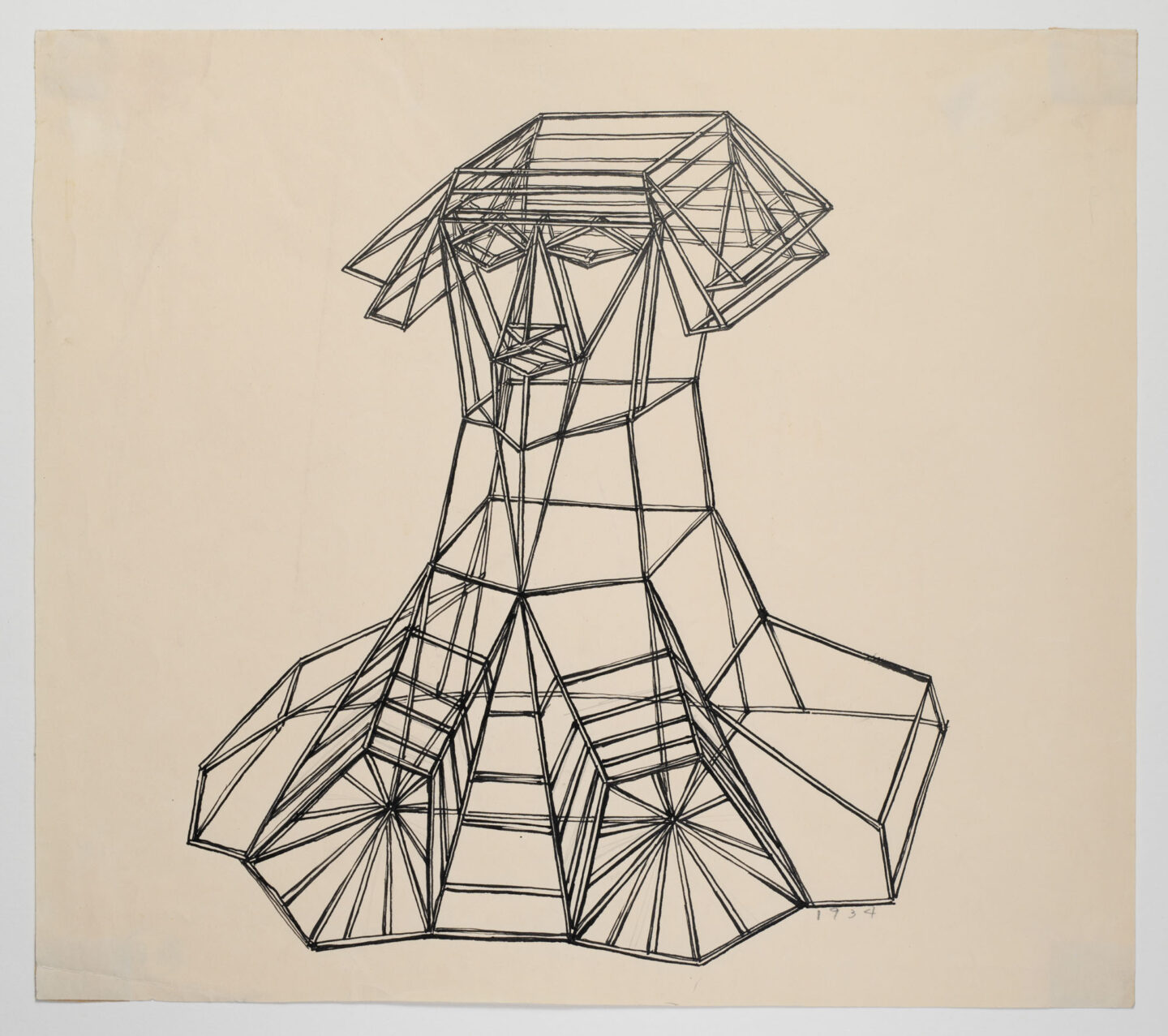

Uhlmann’s foray into artistic practice came by way of the technical. He initially studied mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule before beginning to work as an engineer. In his spare time, he dabbled in sculpture, taking part in exhibitions now and then. In October 1933, Uhlmann, who was at the time a member of Germany’s Communist Party (KPD), was detained by the Gestapo with the charge of ‘preparing for high treason’ and was sentenced to one and a half years in prison. During his incarceration, Uhlmann found psychological freedom by pouring himself into his art, developing amongst other designs the concept of a ‘wire sculpture’ which he realized after his release. Throughout the evolution of his practice, his early work remained highly influential – “the most important period in my artistic development,” in his own words.

“He decided on metal quite early on and then challenged the material again and again.”

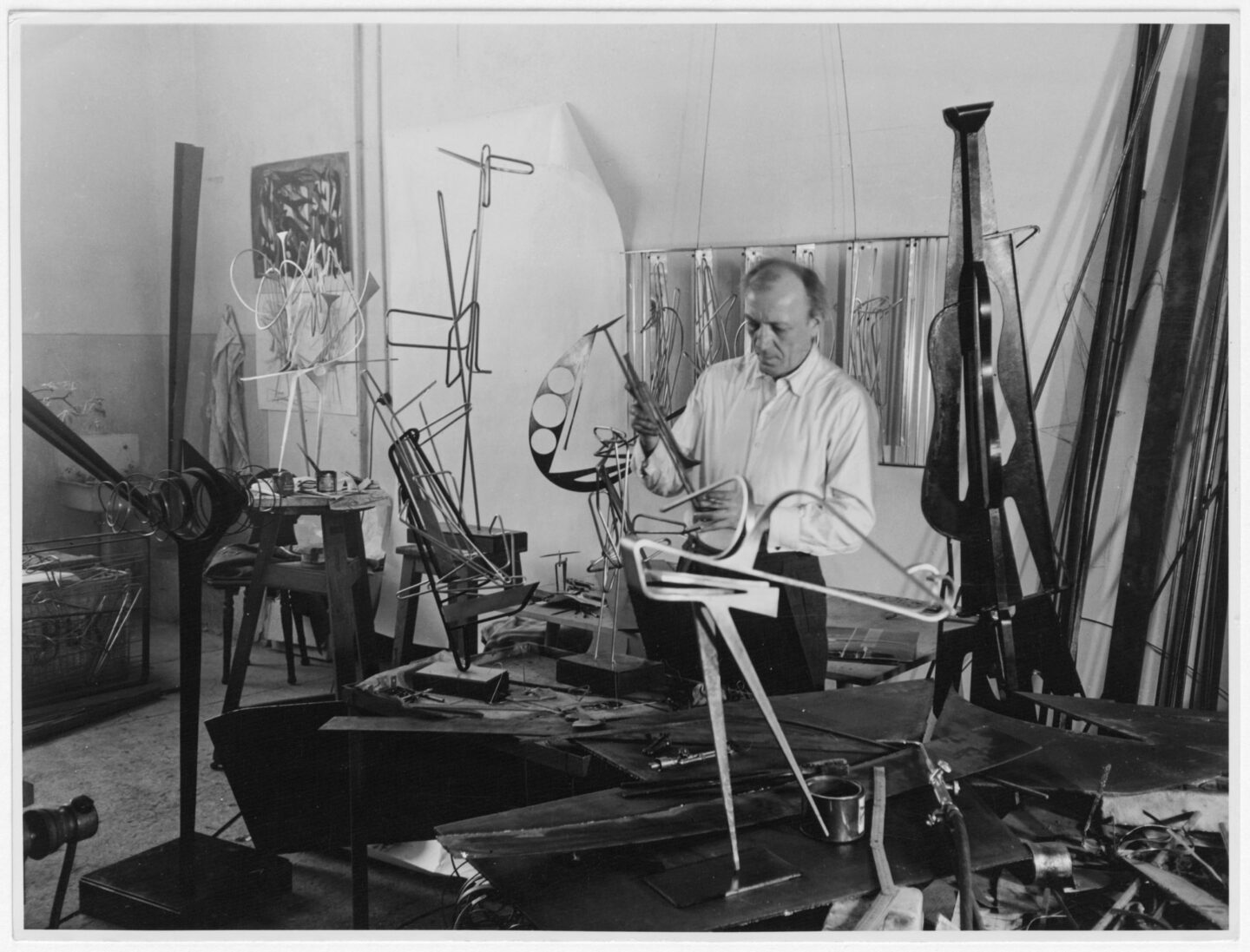

Following the end of the Second World War, Uhlmann chose to forgo his engineering career and dedicate himself wholly to his art as both a practitioner and curator. He immersed himself in West Berlin’s art scene, organizing exhibitions for the Berlin-Steglitz district and later Galerie Gerd Rosen. His own works post-1945 display relentless material experimentation. “Uhlmann’s artistic practice was characterized by experimentation, but also by his extraordinary expertise with regard to materials,” notes Berlinische Galerie Curator Dr. Ilka Voermann. “He decided on metal quite early on and then challenged the material again and again.”

In addition to solid plaster figures and bronzes, Uhlmann continued to develop his wire sculptures, replacing the fine wire with thicker iron rods, which, when warped, appeared as figures drawn in space, in the exploration of the themes of dance and movement that preoccupied Uhlmann at the time. “Uhlmann was interested in ‘overcoming matter’ or, to put it more simply, he wanted to make his preferred material – metal – appear weightless,” Dr. Voermann says. “Movement and dance in particular served him as a thematic point of reference here. Uhlmann once compared the desired effect of his sculptures to a dancer whose training remains invisible as they float across the stage.”

In 1950, Uhlmann took on a teaching position at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste (today’s Universität der Künste) in Berlin-Charlottenburg. The financial security this new chapter offered him gave rise to new opportunities such as an expansive studio space that enabled the creation of more technically complex large-scale works. His sculptures grew in size and untethered themselves from representation. A clarified material palette exclusively comprised metal, with which Uhlmann continued to explore themes of movement and dance, folding and unfolding.

Image © Harry Schnitger

Image © Harry Schnitger

During the 1950s, visual art became central to West Germany’s efforts to present itself as a free and democratic modern nation. Amidst an emphasis on modern and non-representational art — which had had been derided as ‘degenerate’ under National Socialism — Uhlmann’s abstract metal works were lauded both in andany beyond West Berlin. “In 1950, Galerie Günther in Munich organized a solo exhibition at which he was seen by important art historians and critics such as Werner Haftmann and Ludwig Grote,” Dr. Voermann says. “Grote was also the key to Uhlmann’s international success. Thanks to him, Uhlmann’s works were exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1954, followed by further exhibitions in the USA and Brazil.”

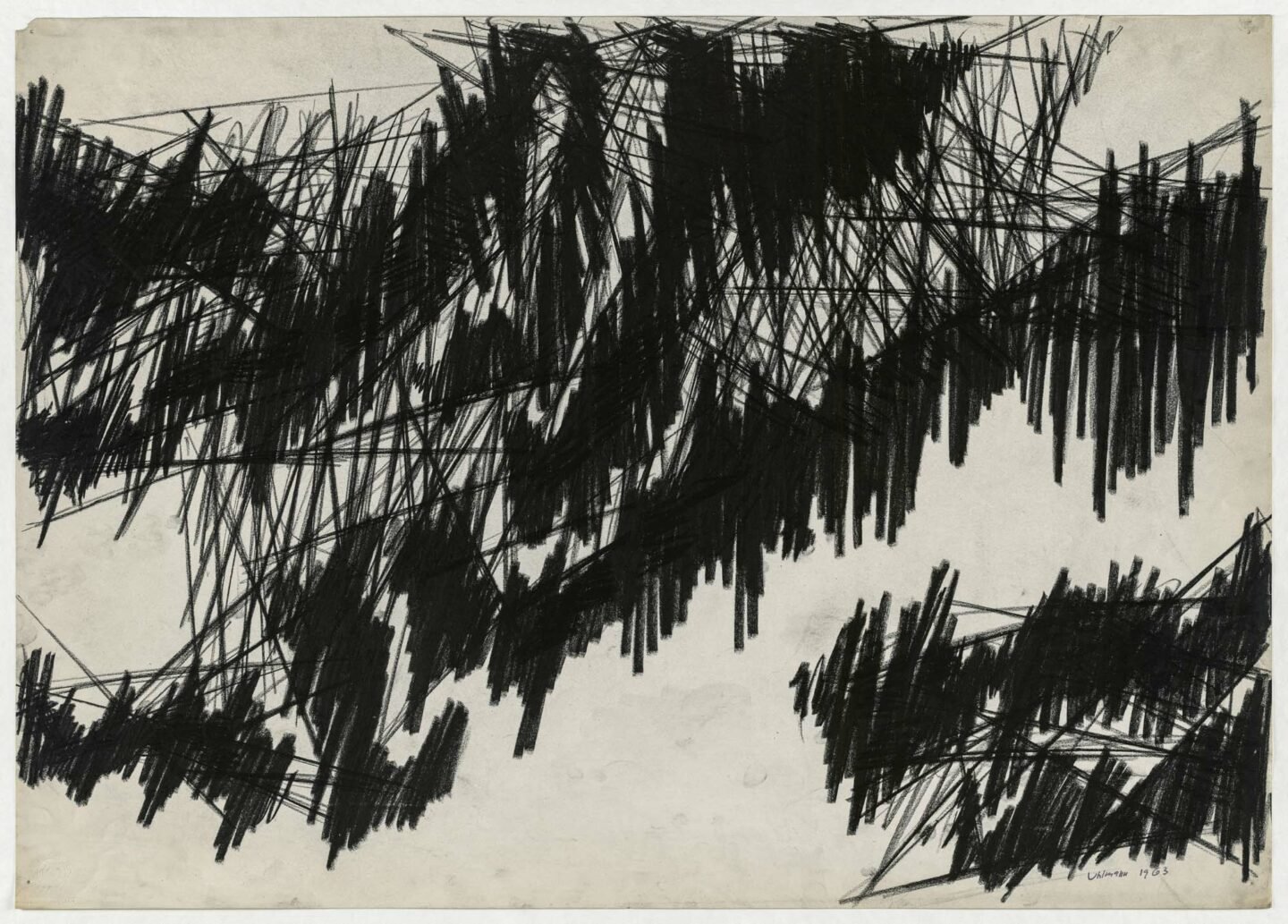

In the 1960s, alongside chalk drawings that offered a more experimental form of expression, Uhlmann dedicated himself to ‘percentper cent for art’ projects, through which he explored the motifs of ‘tower’ and ‘column’. Both of these he viewed as spaces built around an inner life; more permeable than fortified. Between 1954 and 1972, he created seventeen publicly commissioned works which have since become ingrained in the urban fabric of several German cities as well as in Rome.

In the west of Berlin, four large-scale works engaged in dialogue with cultural institutions and icons of modern architecture: in the foyer of the concert hall of Universität der Künste (1954), on Hansaplatz amidst the surrounding Hansaviertel’s embodiment of utopian city planning (1958), the aforementioned ‘Untitled’ sculpture that points skywardds in front of the Deutsche Oper (1960–61) and on the roof of the Berlin Philharmonie (1963). As emblems of West Berlin’s aspirations for modernity, each quietly preserves its past, eternally stretching towards tomorrow.

Hans Uhlmann: Experimental Forming is on view at the BerlinischeBerlinsche Galerie until 13 May 2024. For more on the exhibition, visit the exhibition website.