Hospitality’s Next Era: In And Beyond Flussbad, Slowness Reimagines the Possibilities

- Name

- Flussbad

- Images

- Clemens Poloczek

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

Boutique hotels and global membership clubs have had an outsized influence on the 21st century hospitality landscape. Twenty-five years in, amid our hyperconnected context of cultural sameness and climate awareness, many are questioning what our predominant modes of going and staying truly offer. Is there a way forward that nurtures rather than depletes? How can we reconnect with places, people, and ideas in ways that feel grounded and real? Charting the course for answers is Slowness, the experiential hospitality collective co-founded by Claus Sendlinger, whose creation of Design Hotels in the early ‘90s helped catalyzed the boutique hotel movement. In the next era of his team’s vision, Slowness is redefining what hospitality brings to the table. Ignant experienced its flagship project in Berlin, the Flussbad Campus on the eastern reaches of the Spree River, where the category-eluding Reethaus stands as a stoic centerpiece. An exploration of how Slowness’s life-centered philosophy honors the connections between all living things, and strengthens the bonds between them.

01 A Fluid Field

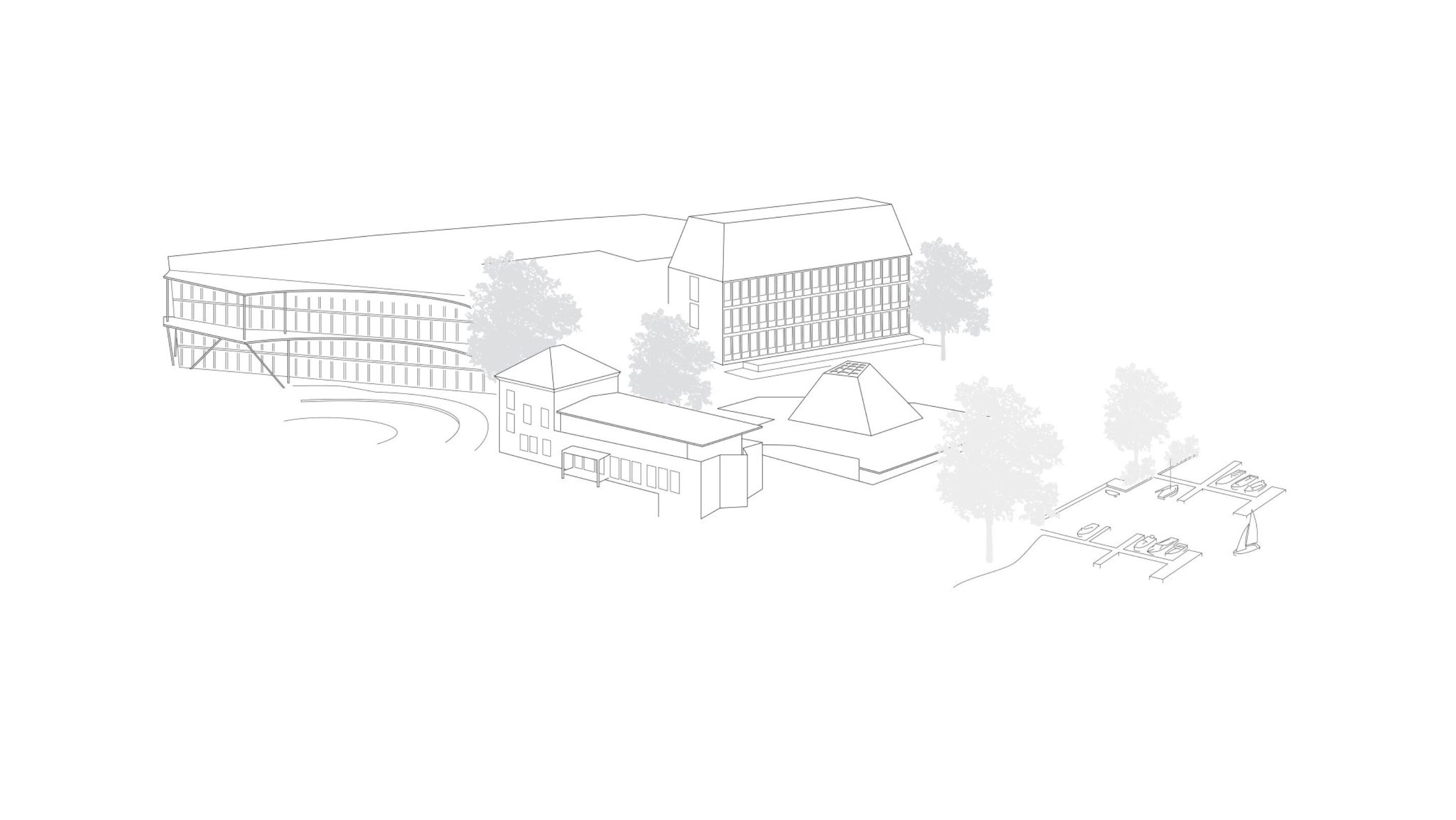

A cluster of structures, primeval and post-industrial, rise from a rewilded field along eastern reaches of Berlin’s Spree River, overlooking the great green expanse of Treptower Park on the facing bank. Industry, leisure, and commerce have long shaped the story of this 12,000 square-meter site on the Rummelsburger Bay in the city’s eastern district of Lichtenberg. In 1927, during the Weimar era, it hosted the open-air Lichtenberg Municipal River Baths, set adjacent to a power plant whose runoff water heated its pools in winter. The power plant remains functional today, a landmark of the enduring industrial character of Berlin’s Lichtenberg district. From the 1950s until German reunification, the site housed an East Berlin customs office, until its eventual abandonment and reclamation by nature saw it set the scene for illegal parties that defined the heady days of the city’s 1990s rave culture.

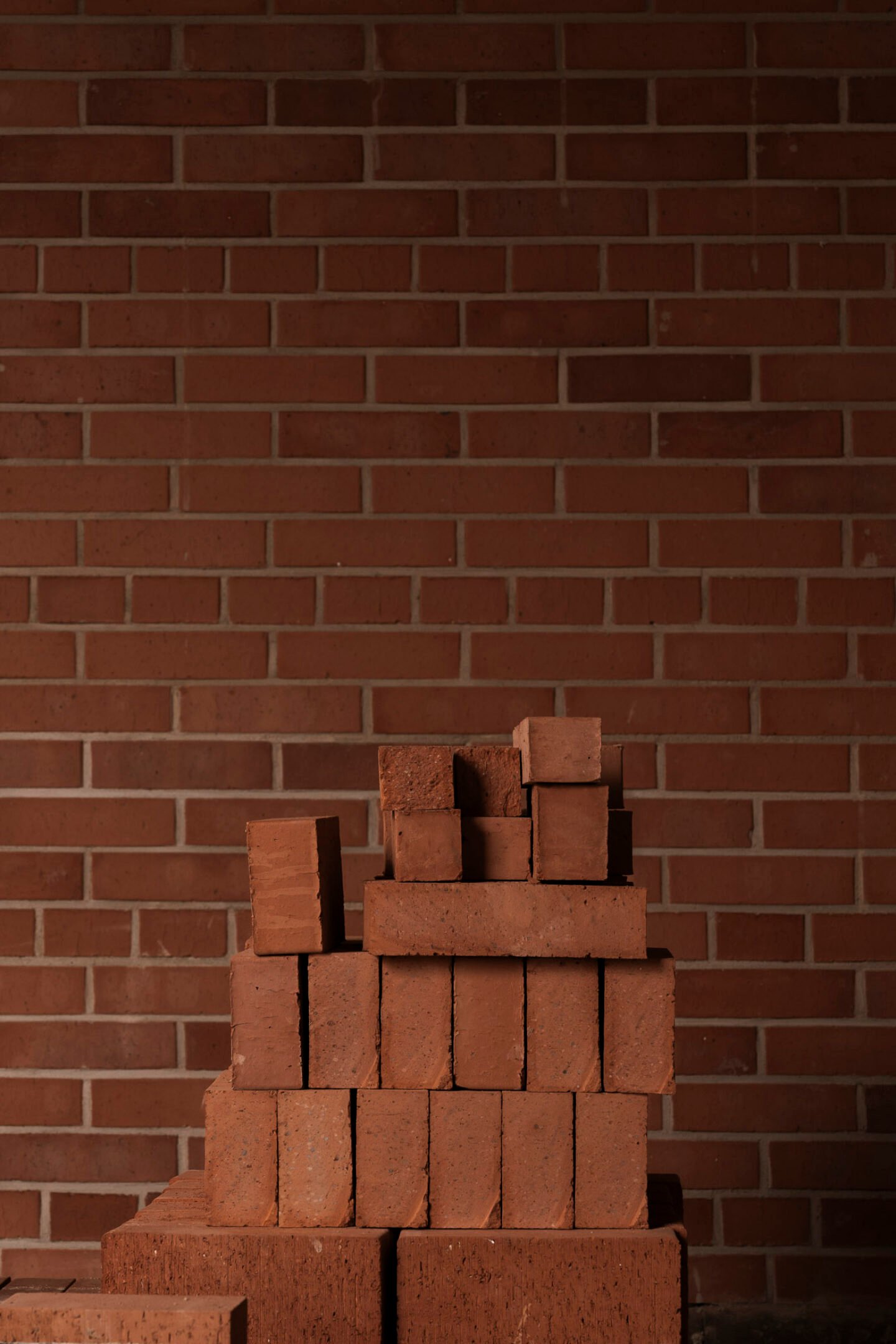

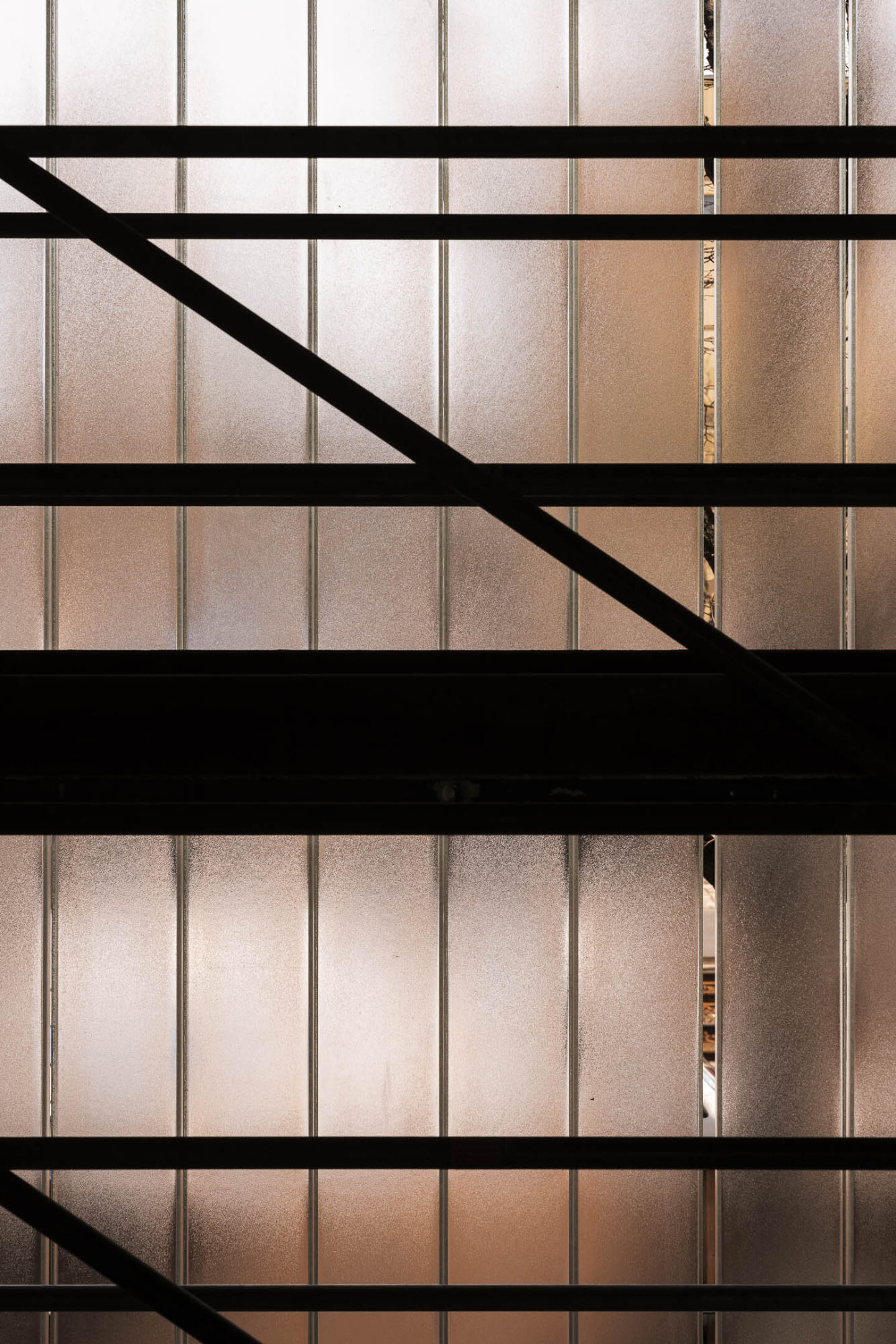

Today, the land is opening a new chapter of its history, authored by the experiential hospitality collective Slowness, founded by Claus Sendlinger, who previously established Design Hotels, together with Peter Conrads whose long career in consultancy and investment includes the re-organization of the United Nations in the early 1990s. Flussbad’s first completed milestone, the Monika Gogl-designed Reethaus, rapidly imprinted itself on Berlin’s cultural consciousness following its opening in 2023. The glass and concrete structure with its trapezoid, hand-thatched roof houses a bunker-esque performance space that takes cues from “ancient temples, caves, and other natural voids”. Transmitted through a 360-degree sound system, the genre-eluding programming by Soundwalk Collective gives the floor to an eclectic line-up of sonic performances that invite “radical presence”. Invitations have welcomed visitors a listening session for recordings of the Gyuto Monks Tibetan Tantric Choir, or a live performance by the singer and composer Walid Ben Selim.

02 Revitalizing Community

In the coming twelve months, Reethaus will be joined by the completion of new and adaptively reused buildings, including ‘Werft’ by Berlin’s brutalist auteur Arno Brandlhuber and Swiss architect Christian Kerez and ‘Bootshaus’ by holistic placemaking studio Realace. “Flussbad has an interesting quality between Lichtenberg, with the power plant, very rough on the edge,” notes Claus Sendlinger. “On our side, everything is green. The design of the Reethaus is melting into this piece of green that we’re protecting here.”

Eventually, Flussbad will comprise an auditorium and gallery, library, a restaurant and bar, ateliers, working lofts, and hotel rooms, and a health and movement studio. Cold and warm therapy, movement, and meditation will be joined by functional medicine, personal training, and lifestyle consulting advice. Once in full flow, the campus will operate on a multi-dimensional membership model, which was recently prefaced with the launch of the Friends of Reethaus membership. Multiple modalities of engagement will invite like-minded locals and itinerant creatives opportunities to participate in elements of interest – attend a performance or a lecture, work in the library, dine at the restaurant, or immerse themselves in the campus’s health and overnight stay offerings. In short, to join a community that speaks to them authentically, offering the opportunity to connect and exchange in person across disciplines, backgrounds, and life stages.

“What we see here at Reethaus is a need for an interdisciplinary belonging,” says Ann-Kathrin Grebner, Slowness’s Curatorial Director. “You want to get in touch with different groups and different fields. This is what we see here – the scientist researching aging is talking to the guy who’s a superstar in the cultural world. There’s an understanding for connecting in a deeper sense and purpose, especially as we’re overwhelmed with so much information. It really shows us that when people go into details, they connect differently. That’s what the campus is built for. It also gives the chance to make something collectively. It’s one thing to say, let’s join a community. But what’s your contribution to that community? You need to support people to actually contribute; to go from passive consumption to getting active.”

03 Better, Not Bigger

The Flussbad campus is one node in Slowness’s network of hospitality concepts, each deeply rooted in locality while distinct in scale, atmosphere, and offering. Collectively, they dismantle binaries between concepts that have been long been pitted against each other within the domain of hospitality: the rural and the urban, architecture and agriculture, presence and pleasure. In the centre of Berlin, Flussbad is joined by the bakery Sofi, a joint venture developed together with Frederik Bille Brahe and his Copenhagen-based team that became an overnight institution on opening in 2020.

In Portugal, Casa Noble, a guest house and cultural salon in Lisbon’s historic Graça district converted from three historic buildings, finds its rural counterpart in Friends of a Farmer, a regenerative farming project, Friends of a Farmer, strengthens ties between small-scale organic producers and consumers through farmer’s markets, lecture series, and foraging workshops. In Thailand, ‘Slow Wonder’, a collaboration with cultural festival Wonderfruit, explores exchange and dialogue between cultural rituals and traditions and holistic wellbeing.

In their diverse expressions, this growing movement of initiatives is grounded in a new hospitality paradigm that, in the words of Claus Sendlinger, offers a response to the question: “Is there a chance to make things better instead of bigger?” There’s a follow-up: “And what does that require?” The teams’ exploration of answers traces back to rural Ibiza, where in 2016 Slowness, together with Design Hotels established the now-dormant La Granja, a 10-hectare working farmstead organically tended to reframe dialogue around food provenance and cultivation. The idea was to recenter the hotel experience around regenerative principles, inviting guests to connect deeply with the land they were guests on, and contribute to its flourishing.

04 Agriturismo Inverted

The notion behind La Granja isn’t without precedent; Slowness notes the inspiration from myriad movements across eras, and modernizes them for our present moment. A leading reference is the ‘agriturismo’ (agricultural tourism) model initiated in Italy in the mid-1960s. Arising in response to the industrialization of agriculture, its intention was to support independent farmers in an era of rural decline by licensing them to host guests on their land. Claus deconstructs the unforeseen consequences: “With the decrease in small farming and the increase of tourism, most of the activities were just turismos, no agri, because it was so much easier to rent the rooms than to work the land. Before we did La Granja, none of the agriturismos did agriculture. But it was a jackpot to have an agriturismo license, because it was a jackpot to rent a room. So we flipped it, and we said: tourism can really support amazing products in terms of farming: hand farmed, zero pesticides, zero fertilizers, an organic farm.”

La Granja acquired somewhat of a legendary status that has only grown since its closure. Its spirit is carried forward in Slowness’s farmstead project currently in development on Alentejo’s Arrábida Coast, led by the same Master Farmer who tended to La Granja. Cohering around a central farmhouse, the 120-hectare property will comprise private houses and hotel rooms with an offering of experiences that echo the ethos of the Bauhaus or the avant-garde Black Mountain College founded on a North Carolina farm in 1933. A health center and a fourteen-hectare biodynamic farm hosting a destination restaurant will be joined by a school of crafts established together with an architectural team from Lisbon who has devoted themselves to cataloguing the craftspeople preserving Portugal’s artisanal traditions.

05 Locally Rooted, Life-Centered

While every Slowness concept is inherently singular in reflection of its surroundings, all cohere around a common philosophy. “Our deal here, what we did with the farm, is to find others who are thinking the same – life-centered, holistic, circular – and build it all in,” Claus says. “It’s not just selling rooms in a beautiful setting with good food. How can it go back to the land? How can it go back into the communities?” His citation of ‘life-centered’ refers to an emerging approach, grounded in environmental ethics, that looks beyond human needs to account for long-term ecological and social considerations. In short, it honors the interconnectedness of all living things.

Health – of individuals, communities, and ecosystems – is accordingly a central throughline Slowness places and projects, in reflection of the collective’s mantra of ‘cultivating arts, crops and inner gardens’. “Through the arts, we create connections and discourse and find people who we believe will have a lot to share together,” Claus notes. “The crops are where the food is all coming from, either planted and grown by ourselves, or with similar-minded people in the region. The inner garden is really the mind part of personal development. These things will always be covered. How they will be executed depends on size, location, seasonality.” The ultimate aim is a mindset shift for approaching an industry that has long been accepted as depletive. “We believe that hospitality can be a force for good,” Claus states. “That’s really why we’re doing what we’re doing. And that’s also what we want to show: that doing things better rather than bigger can also be tremendously successful. It takes more mind; it takes more energy; and the business model needs to shift, maybe, a little bit.”

06 The Near-Missed Landmark

In its second year of existence, the Reethaus was named by Time Magazine as one of 2024’s ‘World’s Best Buildings’. Its reception, locally and internationally, positions it as an emblem for Berlin’s emerging creative era: more polished, better funded, but as fluid and boundary-pushing as ever. Yet the campus taking shape around it might never have manifested in its final form. Claus recalls the moment he and Peter viewed Brandlhuber and Kerez’s first presentation for Flussbad’s ‘Werft’ building. Its initial concept was presented in the form of a six square meter model in Kerez’s Zurich office. He went into the meeting anticipating a ‘classic Brandlhuber’ – formal and austere, akin to the Antivilla that was under construction at the time.

To his great surprise, “The building was full of curves,” he recounts of that first tense moment. “I looked at Peter, and said, ‘Let’s step outside.’ I was shocked.” he laughs. “What is this? I thought we were getting a Brandlhuber, but this is completely different. We didn’t know what to say. We listened to both gentlemen, how they were arguing for it and how they were explaining it… I think in a normal moment, I would have said, ‘No, just forget it, it’s let’s restart,’ but their words really triggered something in me and Peter. We said, ‘Okay, let’s just let it sit. Give it a week, then we’re going to look at it again.”

Seven days and substantial reflection later, the architecture for Werft was greenlighted. Building restrictions would eventually sharpen its soft edges, but some curves remain. They quietly nod to Louis Kahn’s Ayub National Hospital in Dakar, Bangladesh, which Kerez had visited with his students shortly before the first presentation to Slowness. Claus remains just as captivated as Kerez was by the hospital’s sweeping volumes. “Now, many years later, as I’m walking through the building every day, showing interested tenants around, I can see Kahn,” Claus says. “But he’s hidden. It’s a Brandlhuber-Kerez.” Even for the hospitality veteran, with his specialism in actualizing architectural vision, there was an alchemy to Flussbad’s built atmosphere that he couldn’t have anticipated. “I’ve seen hundreds of hotels growing from nothing, so I would normally have a good sense of what is going to be,” Claus reflects, “but this building really left me almost speechless. When the floors were being poured and the scaffolding was up, you could not feel the real power of it. Only when the concrete was dry did you go in and say, ‘Wow’.”

Opportunities to become part of the Flussbad Berlin campus include available spaces such as studios, ateliers, and offices for rent. Find out more and enquire via flussbad.com/join.

Images © Clemens Poloczek | Text: Anna Dorothea Ker