George Nakashima Woodworkers: A Legacy Carved in Time

- Name

- George Nakashima Woodworkers

- Images

- Monika Mroz

- Words

- Monika Mróz

Stepping onto the grounds of George Nakashima Woodworkers feels like entering another world—a quieter, more refined realm. The soft light, unhurried sense of time, and almost tangible peacefulness create a space for reflection. A network of thoughtfully placed structures invites gentle exploration, each one revealing another chapter of Nakashima’s creative journey and a story shaped by time.

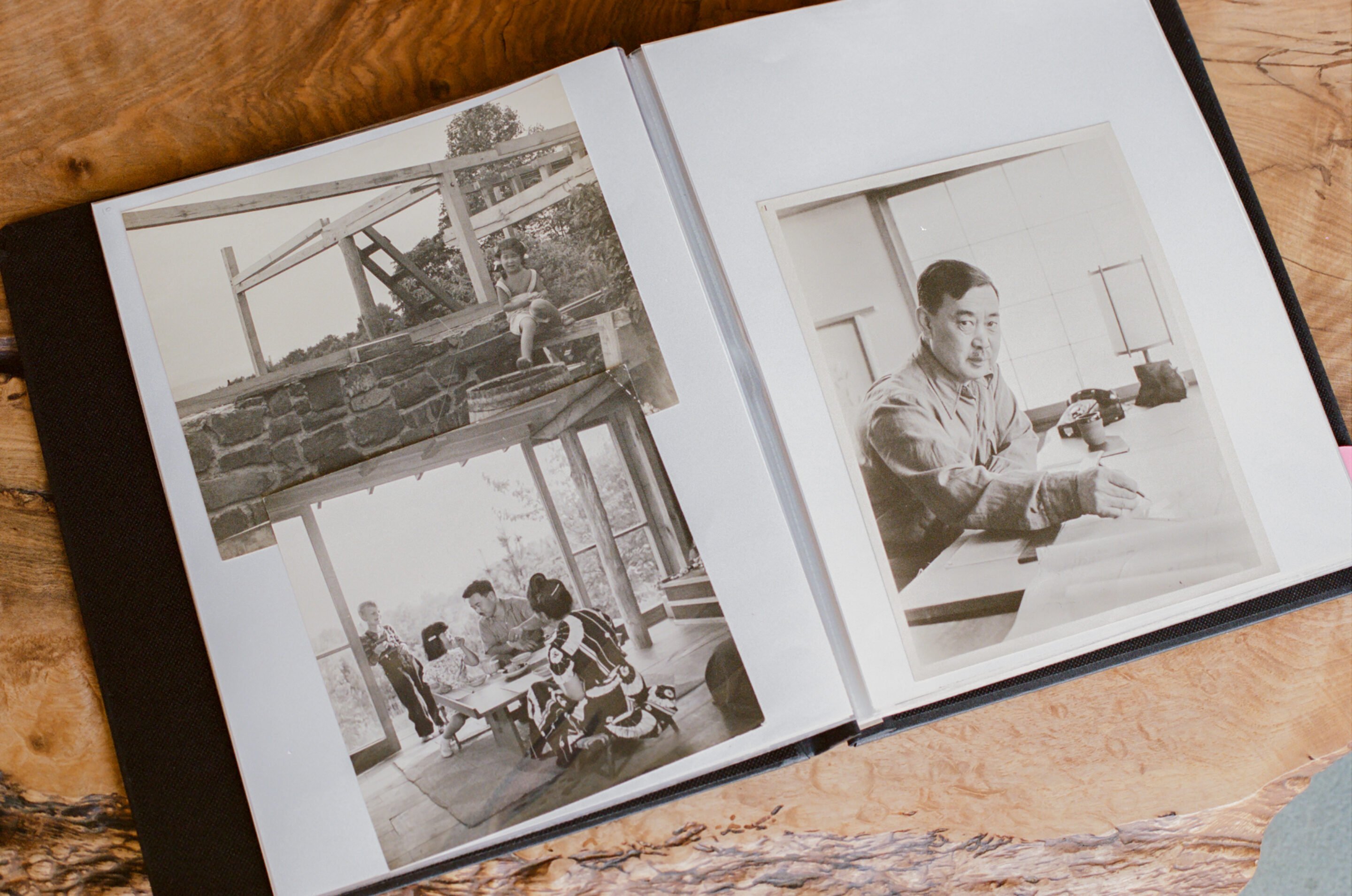

It all began around 80 years ago with one man’s quest to master the art of woodworking and provide for his family. Much like his creations, the premises of Nakashima Woodworkers are inseparable from the surrounding nature, serving as both a living archive of design and a testament to a deeply personal legacy.

Today, George Nakashima’s vision lives on through his daughter, Mira Nakashima. An accomplished designer in her own right, she has preserved the family business while establishing her own name in the design world. In the family’s former living room—a space once filled with conversation and laughter—Mira reflects on the decades of artistry, innovation, and timeless design that continue to define this unique place.

What was your childhood like? It must have been quite curious for a child to be constantly surrounded by creativity and the act of making.

I suppose it was interesting, though I didn’t know any different. I was born in Seattle, and when I was six weeks old, we were incarcerated in the Idaho desert. After that, we were sponsored by Noémi and Antonin Raymond, who had a farm down the hill, where we lived until 1945. My father worked out of the garage back then, and when I was about 5 or 6, he found this property. He couldn’t afford it, so he paid for it in labor, and we lived in a tent where the lumber sheds are now. I remember growing up in that tent, surrounded by poison ivy. Dad would carry us over it to avoid rashes. First, he built the shop to have a place to work and then, little by little, he built our first house.

We didn’t have television, and I was an only child for 13 years, so I didn’t have any playmates. The men in my father’s shop became my friends. I would play in the shop with pieces of wood and sawdust and make things from berries I picked outside.

I can imagine it must have felt like a great playground for a kid.

Yes, it was nice—much more rural than today. In the beginning, there were only two men working in the shop, and there weren’t any big machines yet. The traffic on the nearby road was much lighter too, so it was mostly very quiet.

Did your father encourage creativity in you and your brother, or was it more of a byproduct of spending time together?

I don’t think he actively encouraged creativity when I was young. I was good at art—drawing, painting—and my parents supported me in that. But I was also studying other things like French, math, and music. Actually, I started music with one of the men in the shop when I was about ten. He and his wife didn’t have children yet, so they would take me folk dancing in Princeton every week and taught me to play the recorder, which became my first instrument. I developed a real affection for music during those times—we’d sing rounds in the car all the way home.

I also had an “aunt,” Aunt Milly though she wasn’t my real aunt. She had lost her own child when he was two and became very close to me when I was the same age. I think we were still living at Raymond Farm when I first met her. She took me under her wing, gave me swimming, diving, horseback riding, and tennis lessons, and even took me to The Trapp Family Singers’ camp in Vermont. That camp was wonderful—music all day long, every day!

When I went to college, I was really good at math, but I actually thought I would major in languages. I was studying French, Italian, Russian, and even some Greek. But my father told me, “No, you’re majoring in architecture.” So, that’s what I did.

He clearly had a plan for you.

Yes, I guess so.

So, during your studies, did you ever consider staying in the family business or eventually taking it over, or did you have other plans for yourself?

I wasn’t really thinking about a career at the time. I was just enjoying the moment. At Radcliffe College, I studied architectural sciences, but it was mostly focused on humanities—history, design—nothing specific to furniture making. I didn’t think much about coming back to run the business.

Then, my Aunt Milly decided I needed to visit Japan, and she wanted to go too. In 1963, we joined a Zen Buddhist tour led by Alan Watts. It was an amazing experience—we learned a lot about Japanese culture, history, and traditional architecture. After the tour, I stayed in Tokyo with my mother’s older sister to study Japanese, since I couldn’t speak much of it at the time.

While there, my father’s friends, Junzo Yoshimura and John Minami, helped me get into Waseda University, where I studied architecture. I was way behind my classmates, though—they were doing pencil and pen drafting, while I had only done freehand drawing before. It was a challenge learning both drafting and Japanese. In 1964, my father visited me on his way to India, where he was teaching, and he took me along for a while before I returned to finish my studies in Japan.

Why did you decide to come back home?

I had married one of my classmates and was living in Tokyo when we had our first child. My parents invited me back to the U.S. so they could meet the baby. We moved back just before my daughter Maria was born in 1966. Then, in 1969 or 1970, I was invited to start working part-time in the company.

After your father’s death in 1998, you took over the company. How much of your work is about preserving his legacy and philosophy, and how much of it reflects your own direction and ideas?

When my father passed away, he didn’t have a plan in place. Of course, nobody expects to die… We had a backlog of three and a half years of orders, but many clients canceled because they believed that without my father’s signature, the pieces wouldn’t be as valuable. Some even asked for a 50% discount. That was tough, but for those early years, we tried our best to make the pieces as close to what my father would have done.

There were a few long-time workers who knew my father’s methods well, so together we recreated his designs. When I worked with my father, I always thought it was important to learn how the lumber was processed. I’d go to the sawmill with him, watch how he studied the logs, and figured out how thick to mill them and what he would create from them. That was great training, and I felt confident I could make furniture because I had done all the drawings under his guidance.

What I didn’t realize was how important marketing was. After a while, one client, Mrs.Krosnick encouraged me to do something different. She didn’t want the same designs, and that was the first push I needed to start creating my own work. An art dealer named Robert Aibel told me that I needed to establish myself as a designer because many people saw my work as reproductions and didn’t think they should pay as much for it. Although I explained that the effort and labor to create the pieces remained the same, he encouraged me to develop my own designs and even offered to showcase them in his gallery. So, I did. Little by little, people started to notice. We got publicity, and eventually, clients understood that I could continue making my father’s work while also bringing something new. That’s how we slowly came back.

What was your favourite part of working with your father?

Working in the shop.

Why?

It was just fun. Making things in three dimensions, shaping wood, and seeing how it transformed when it was finished and oiled was really rewarding. You’d start with raw materials and end up with something entirely different—it was exciting to see that process unfold.

When I first started working, my mother had me in the office, typing orders and answering phones. I remember thinking, “I went to architectural school for this?” But when I finished my office work, I could spend time in the shop, which I loved. Eventually, my father had me doing more drawings in the design office. His drawings were very loose—basically freehand sketches on small sheets of paper with minimal dimensions.

I questioned how the team could make furniture from such basic drawings, but my father would tell me they knew what to do. He was always in the shop every day guiding them, and if he didn’t show up right away, they’d wait for him to give instructions. I suggested adding more detail to the drawings so they could work more independently, and that’s when I started incorporating more precise dimensions and a larger scale, which made the process smoother.

I’m sure your father taught you many things, as parents do. But is there something in particular that stayed with you—something you’d want to share with other woodworkers or designers?

Yes, one thing that comes to mind is my father’s book, The Soul of a Tree, which he wrote in 1981. It has been a great inspiration for woodworkers and is still in print today. I think many people found it influential. Interestingly, writing the book was a challenge for him. My mother said he struggled with English in college—she even helped him write the first chapter. She’d tell him, “George, you need a subject, a verb, and an object in your sentences!”

Eventually, he found an editor at Kodansha, who encouraged him to add more technical detail to the book. The first half is more about his history and experiences, but the second half became a practical guide for woodworkers. It includes joinery techniques and methods he learned in Japan. I think that’s why the book remains so popular—it offers both an introduction to woodworking through his philosophy and a practical how-to for furniture making.

It sounds like your family worked as a team, with everyone contributing in different ways. Was it difficult to balance living and working together, or did it feel natural?

It felt like a natural state of things. The shop was always right next to the house, and I think my mother probably sent me out to play in the shop when she got tired of watching me. So I was always there. The atmosphere was very familiar, and it still feels that way today. When you walk around the property, everyone feels comfortable. I remember in the summertime, when it was really hot, my mother would make Kool-Aid—cheap and full of artificial flavours, but cold and wet. We’d mix up pitchers and take them to the men in the shop. It was a nice little tradition.

That actually brings me to my next question. Why do you think it feels so peaceful here? That’s the first thing that struck me—it’s a workshop, people are working, things are happening, but there’s this serenity in the atmosphere as you walk around.

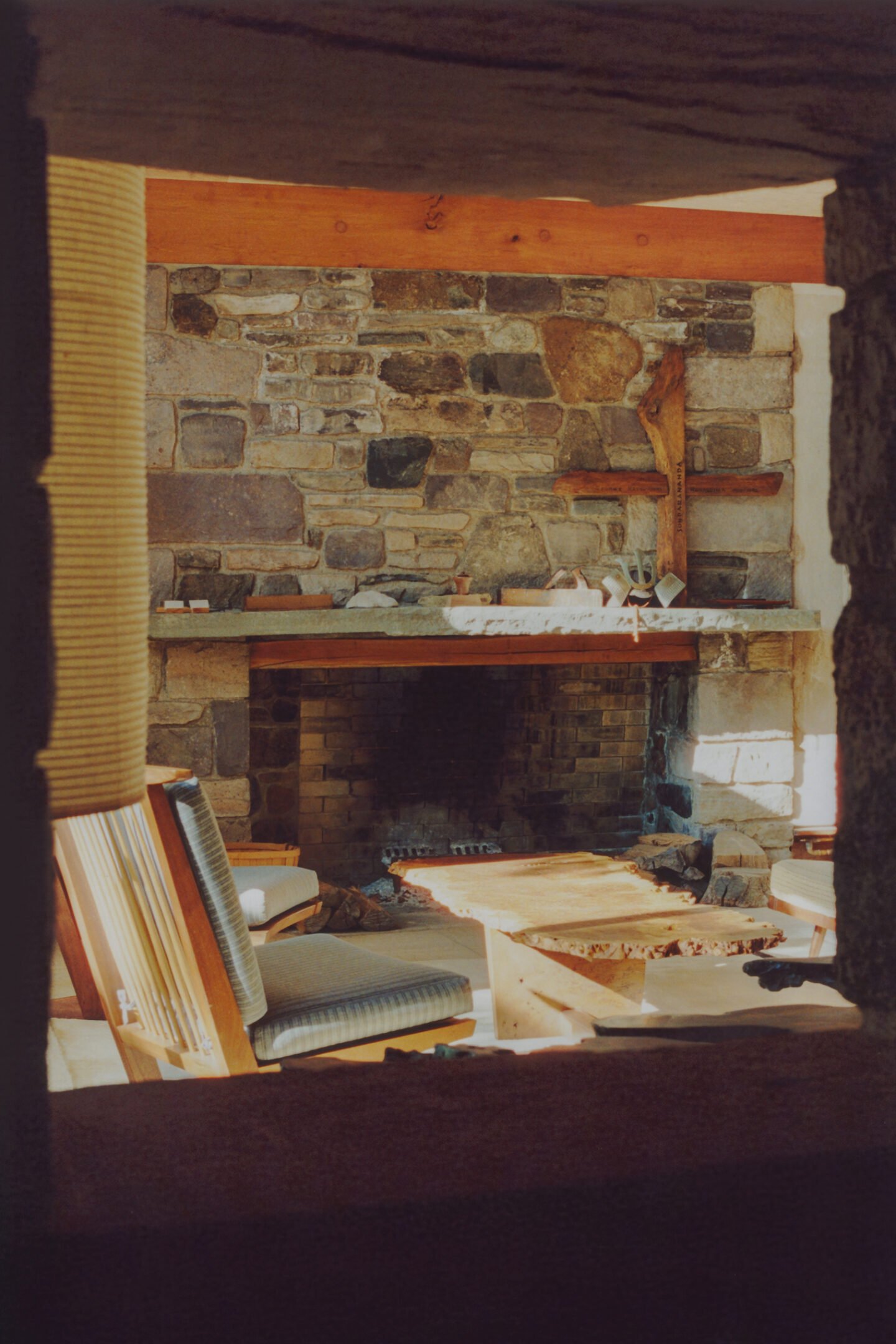

That’s a bit mysterious, even to me. I don’t fully know why, but I think part of it goes back to when my father found this piece of land. We were living in a small cottage at the time, and he was drawn to this property because it’s a south-facing slope. It had been farmed before, but nobody lived here. Even though he didn’t have the money to buy it, he was determined to live here. Back then, it was mostly farmland around us, so it was very quiet.

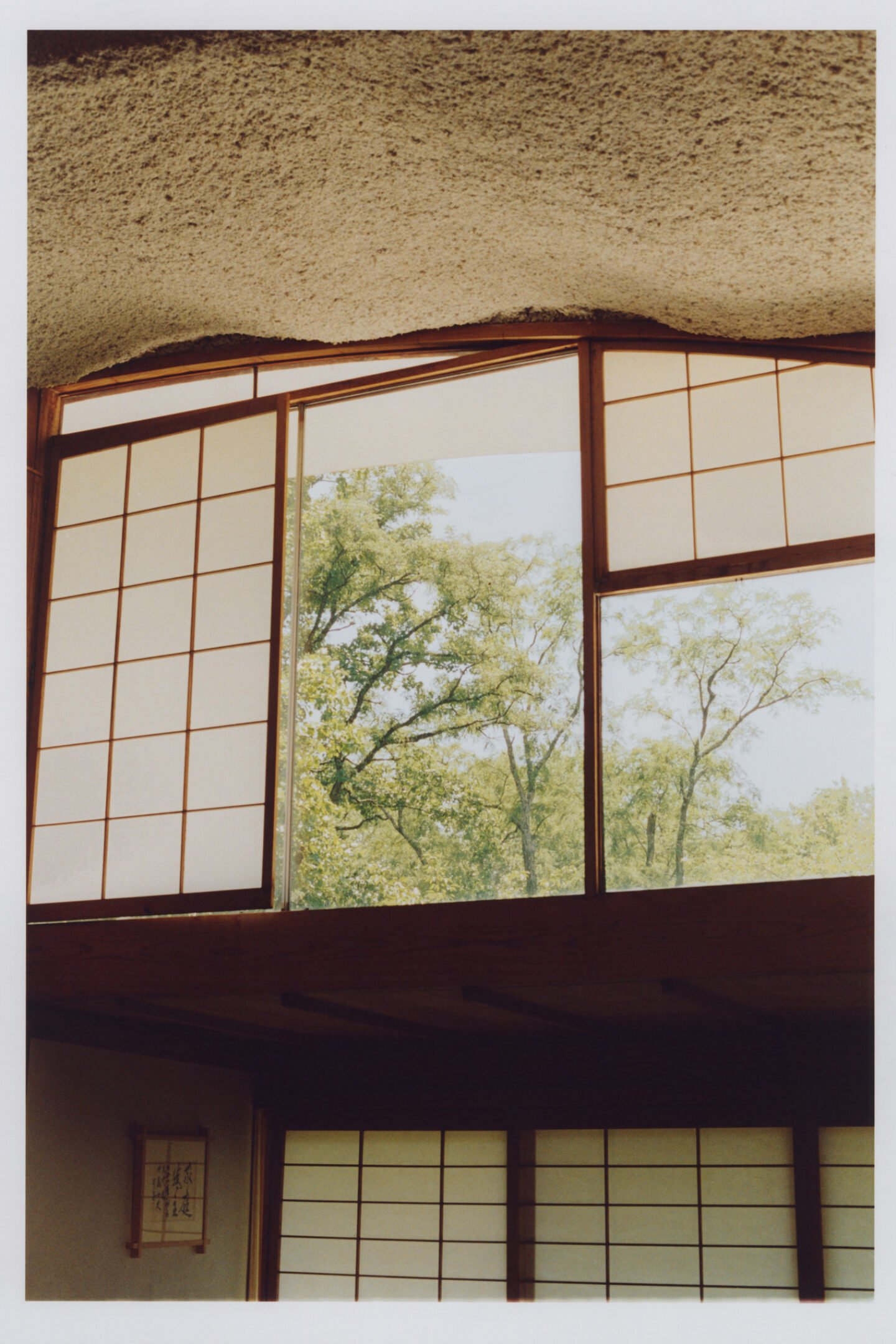

I think the peacefulness also comes from the architecture. My father designed the buildings to fit into the landscape and allow the outdoors to be part of the interiors—something that’s very much in line with Japanese architecture. It creates this sense of harmony. While we do have some noisy machines in the shop, there’s a lot of handwork, which requires focus and concentration. That kind of work naturally brings a sense of calm.

The way George Nakashima talked about trees sounds almost spiritual. Could you share more about how he developed this philosophy, both in woodworking and life?

When my father worked in the Raymond office in Tokyo, he developed a deep understanding of how architecture could harmonise with the landscape, thanks to his friend, Junzo Yoshimura, who showed him traditional Japanese architecture. He saw how, unlike Western architecture, Japanese design integrates the landscape rather than shutting it out. That was a big influence on him.

One of his projects in Japan was a church built in Karuizawa using materials sourced from the land itself—wood from the trees and stone from the ground. It was a type of indigenous architecture, and the building relied on master carpenters who had an instinctive understanding of nature, passed down through generations. This experience shaped his belief in using natural materials and working closely with them.

His reverence for trees also started in Japan, where carpenters would spend years selecting the right timbers, and he was inspired by the Japanese practice at the Ise Shrine, where trees are planted specifically for rebuilding the shrine every 20 years. Beyond Japan, his love for trees was also rooted in his childhood in the Pacific Northwest, where he spent a lot of time hiking and camping as a Boy Scout. In fact, he studied forestry for two years in college before switching to architecture. His connection to trees stayed with him throughout his life, and he always believed in giving trees a ‘second life’ through his work.

It still feels like you have a lot of contact with nature here, being surrounded by trees and the forest.

Yes, the trees are such a big part of the environment here. I’ve seen old pictures of the house, and back then, the trees were small—you could see all the way to the mountains. Now, the trees have grown so much, you can’t see the mountains at all.

It’s like they grew up with you, in a way.

Yes, exactly.

Do you have a favorite tree on this property?

Oh, probably the Japanese maple my grandfather planted. It has this beautiful curving structure and really thin leaves. It’s a Weeping Thread-leaf Japanese maple, and it’s stunning. My grandfather lived in Portland, Oregon, and helped start the Japanese garden there. There are trees there that look similar to this one, and I think that’s why it’s my favourite.

In the fall, the tree turns a brilliant shade of orange, but only for a few days before the leaves curl, turn brown, and fall off. It’s a reminder of impermanence, which is a key part of the Japanese aesthetic. The beauty is fleeting, like the cherry blossoms—so brief, but that makes them more precious. You really have to pay attention and appreciate the moment because it won’t last.

This property has so many buildings, each with its own history. Is there a specific spot or object here that brings back the most vivid or happiest memories for you?

That’s a great question. There are so many layers of memories here, but this table that we’re sitting at, in particular, holds a lot of special ones. It was the center of countless family dinners with friends and family. My mother would often cook in the old house, bring the food over here, and we’d serve it at this table. Many of my parents’ friends were clients—often doctors who furnished their offices with Nakashima furniture—and they became close friends. We’d have them over for dinner, and sometimes they’d mix up their shoes or coats after taking them off when they arrived. So, this table holds a lot of fond memories of those gatherings.

Tables seem like such great witnesses to history—so many stories and meals shared around them.

Absolutely. This table, in particular, is special because it was the prototype for the peace altars my father created. He had a huge tree offered to him by a logger, and he wanted to do something really meaningful with it—peace altars for each continent. The altars were much larger than this table, but the shape was similar. He realised what a beautiful and unifying shape this is, perfect for bringing people together in one conversation, unlike a rectangular table where conversations often split. Round tables have always been used for peaceful discussions, and that was the main idea.

What are the principles of George Nakashima Woodworkers, and what sets it apart from other makers or companies?

That’s a complicated question. When my father first got into woodworking, it was in part a protest against modern architecture. He had studied and practiced architecture in Japan and India, but when he returned to the U.S., he was disillusioned by what he saw. He often told a story about seeing a Frank Lloyd Wright building under construction and being put off by the shoddy craftsmanship—two-by-fours nailed together and covered to look nice, like a stage set. He wanted more control over the process, which is why he turned to furniture, where he could oversee everything from start to finish.

While in Japan, he learned intricate craftsmanship, like using wood joints instead of nails or metal strapping. This precision and dedication to detail stayed with him. In India, where he was supervising the construction of a reinforced concrete building, he demanded strict tolerances and even designed the formwork himself. These experiences shaped his exacting standards for quality.

When we were sent to the Idaho desert during World War II, my father worked with a Japanese carpenter and learned how to use found materials—old crates, leftover construction lumber, even desert plants like Bitterbrush. That time taught him patience, improvisation, and how to work with Japanese tools and techniques that became central to his furniture-making philosophy.

It sounds like he had incredible adaptation skills.

Yes, he really did. He knew how to adapt to every situation. He was a good camper, after all.

So, it started as opposition to modern architecture, but now, having something handmade like this seems even more remarkable.

Yes, back in the 1940s, it was the beginning of mass production, and my father’s work was a protest against that. He believed that if we lost our manual skills and our connection to nature, we’d lose something essential about being human. That’s even more true today, with everything mass-produced in factories.

He felt that in traditional Oriental art, like brush paintings, there was deep respect for natural forms, which artists brought into their work. In contrast, modern art and architecture often ignore nature, driven more by ego and personal expression.

One important lesson my father learned during his time at the ashram was about sublimating his ego. It was a struggle for him, but once he learned it, he insisted on applying it to the work in the shop. Not everyone understood that, and it sometimes caused conflict, especially in a Western culture that values individualism so much.

We are all taught in a way to always strive to doing something different than others, of being unique.

My dad did understand the necessity of mass production to some extent, though. In the 1940s, he designed a line of furniture for Knoll Studios and produced a lot of the prototypes himself in his old workshop. He knew that mass production had its place, but he insisted on keeping the rights to make the pieces by hand in his shop.

He also designed a second line for Widdicomb-Mueller in the 1960s, using new technologies like veneer bending. But when they started changing his designs without telling him, he stopped working with them. He felt strongly about controlling the product from start to finish—from the tree, through the lumber sheds, all the way into the workshop. That control allowed him to adjust designs as they progressed, because a piece always looks different on the bench than it does on the drafting board.

Who do you think influenced your father as a designer or artist?

People often ask if he knew Wharton Esherick, who was an early woodworker here in Pennsylvania, but I don’t think they ever met or talked. One of his best friends, though, was Harry Bertoia, the sculptor from the early Knoll days. They would talk a lot, but not about form or technique—Harry worked in metal, and my father in wood. Instead, they discussed the philosophy of art—what art is, why it exists, and how it should fit into people’s lives. For my father, furniture was always a form of art, but it also had to be practical. If it wasn’t useful, it wasn’t good design. Harry felt the same way about his furniture designs.

Did your father know Isamu Noguchi? I read they have crossed paths.

Yes, they knew each other, but they weren’t close friends. Isamu was part of that same group of designers from Knoll in the 1940s, but he was doing his own thing in New York, while my father was working in Pennsylvania. They met a few times but never collaborated, though I’m sure they respected each other. After they both passed, the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C., organised a Nakashima-Noguchi exhibition. Their work—Noguchi’s Akari lamps and my father’s furniture—went together beautifully. It made me wish they had done a show together during their lifetimes. Toshiko Takaezu, another artist, came to that exhibition. I had hoped to collaborate with her as well, but it never happened.

I’ve seen many great pictures of you and your family when you were a kid. Did you have a photographer friend who took them?

We had a few different photographer friends, but a name that comes up often is Ezra Stoller. He did a complete photographic essay of every building my father designed. He was a very fine architectural photographer, though I’m not sure how their friendship started. Recently, I’ve been in touch with Phaidon, the London-based book company. Jules Spector, who works with them, wants to do an architectural book on my father. Most books so far have focused on his furniture, but this one will highlight his architecture. It’s interesting because my father built buildings the way he built furniture—using the same joints and methods, just like in Japan.

How would you like people to remember your father, both as a maker and as a human being? What was he like?

I remember my cousin, John Terry, did a documentary on my dad that took him 20 years to finish. He interviewed so many people, including Robert Lovett, a builder who worked on almost every building on our property. When asked what my father was like, Robert simply said, “He was different.”

That’s probably the best way to describe him. His Japanese sensibilities, his experience with form and space, and his time in Japan shaped the way he saw the world. In the 1940s, he used rejected lumber because he couldn’t afford high-quality wood, but he found beauty in the natural shapes of the trees. He redefined “free form” in furniture design by embracing the natural contours of the wood, which is what people probably remember him most for.

It’s striking how, here, you can’t forget that the furniture is made from a tree. In highly processed wooden furniture, that connection is lost, but here, the natural form is so present.

Oh, isn’t that beautiful? Yeah, it’s amazing. My father always believed that people use wood as just a material to shape, but he preferred to use the natural shape of the tree as a presence, like it had its own personality and life. He felt that somehow the life of the tree was still within the planks that made the table people live with. He always said the wood speaks to him, and I guess it speaks to the rest of us, too—maybe not as loudly as it did to him. But you have to know how to listen, and be open to it.

What’s the future for George Nakashima Woodworkers?

The future of George Nakashima Woodworkers may involve becoming a nonprofit. We currently run both the Peace Foundation, which preserves my father’s legacy, and the furniture-making business. By combining them under one structure, the furniture business could continue generating income to support the preservation of his buildings, furniture, and archives. This could provide long-term stability for the legacy.

However, we’re mindful of how this change could affect the workshop’s atmosphere. The balance we have now, with a focus on craftsmanship and pride in the work, is important to maintain. If we can preserve that while transitioning to a nonprofit, it seems like the right direction to ensure my father’s vision is carried forward.

Images © Monika Mroz for Ignant production | video © Portblue