The Rational Modernity Of Kleihues + Kleihues Architects

- Name

- Kleihues + Kleihues Architects

- Images

- Ana Santl

- Words

- Jessica Jungbauer

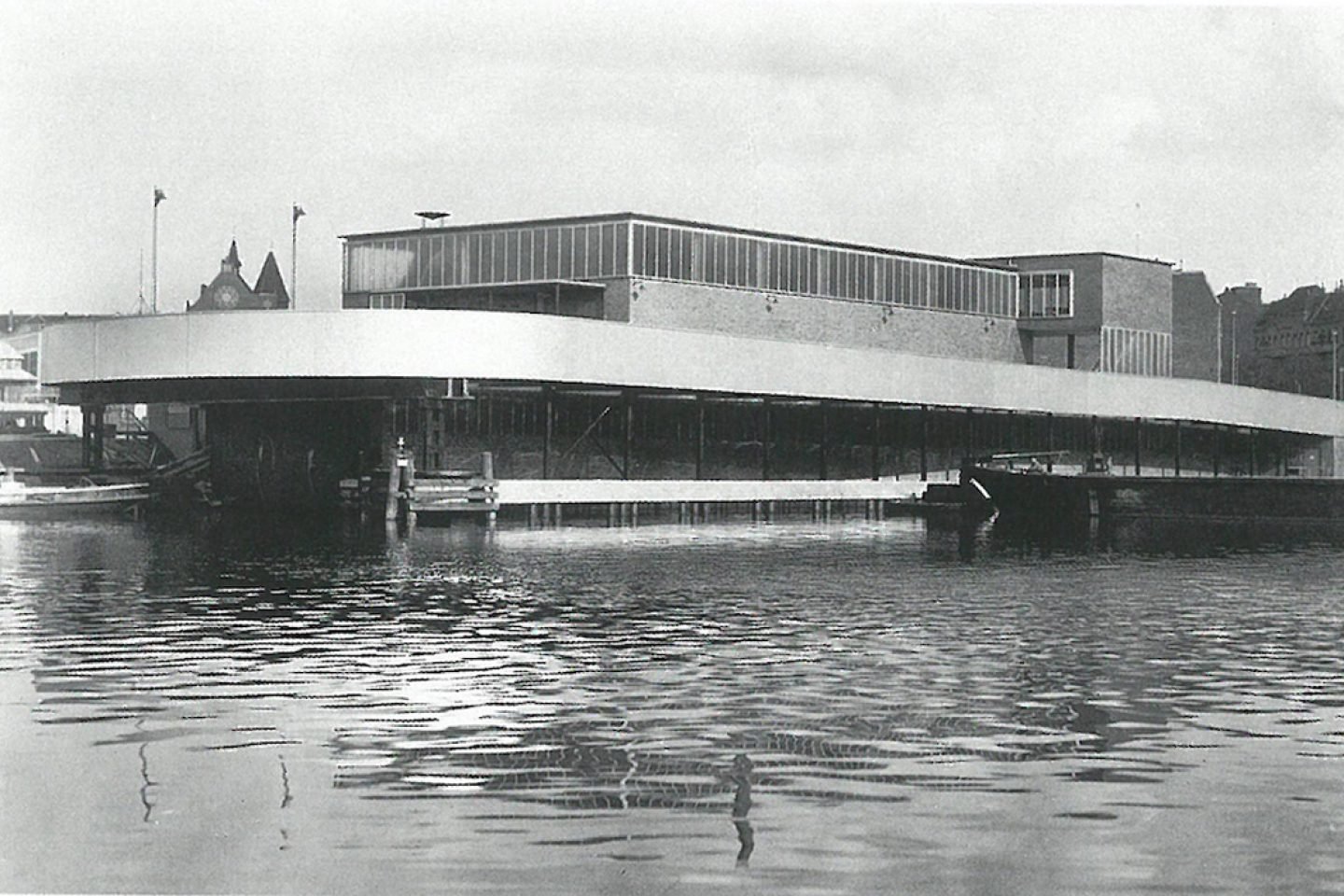

A landmark 1935 building that was once a garbage storage facility today houses the offices of Kleihues + Kleihues architects. It’s in these rooms – which overlook the River Spree in Berlin-Charlottenburg – that architect Jan Kleihues builds on the success of the studio founded in the 1960s by his father, the renowned architect Josef Kleihues.

A landmark 1935 building that was once a garbage storage facility today houses the offices of Kleihues + Kleihues architects.With a reputation for designing timeless modern buildings in the urban space, the studio’s portfolio spans cultural projects such as Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, to hotel and retail buildings, like the 5* plus Sofitel hotel and department store Galeria Kaufhof in Berlin. One of the studio’s upcoming challenges sees the transformation of Kudamm Karree in Berlin.

We sat down with architect Jan Kleihues to talk about the renovation of the historical building into an office space and the studio’s architectural philosophy as well as one of their current projects, the headquarters of the Federal Intelligence Service…

“A building like this is unique. This has to do with the time it was built, the architecture and its function.”Can you please start by telling us more about the history behind this landmark building that used to be a garbage storage facility?

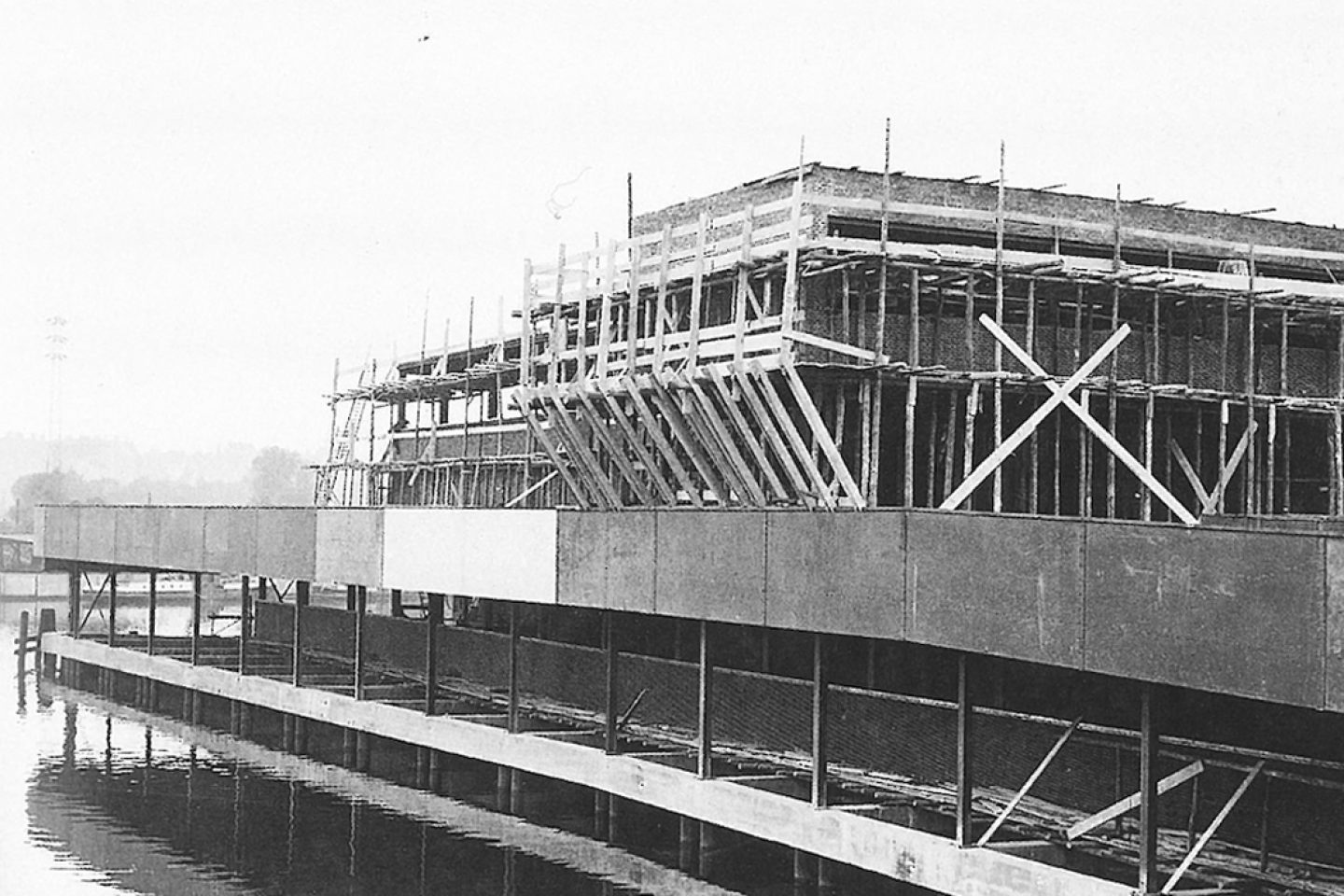

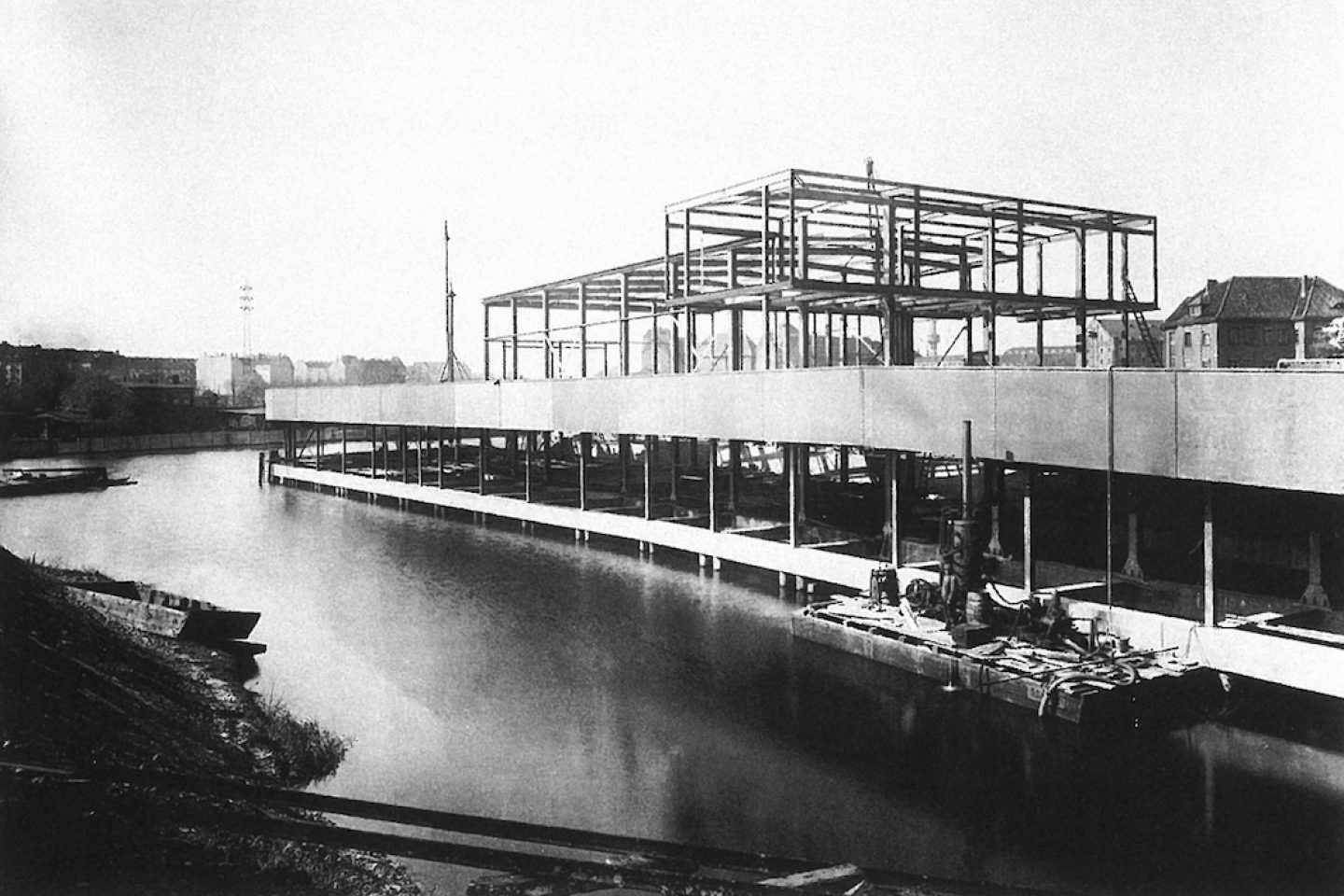

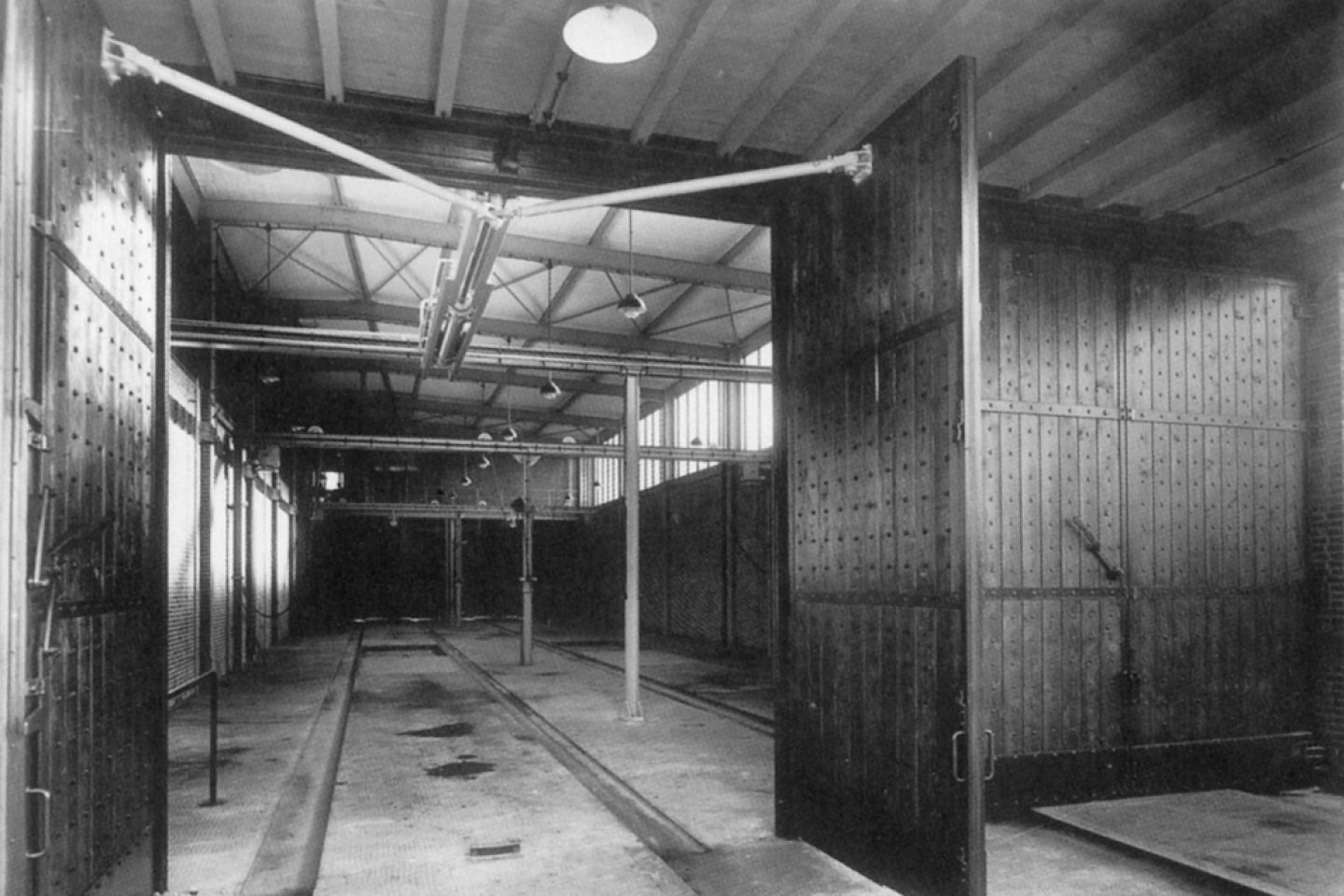

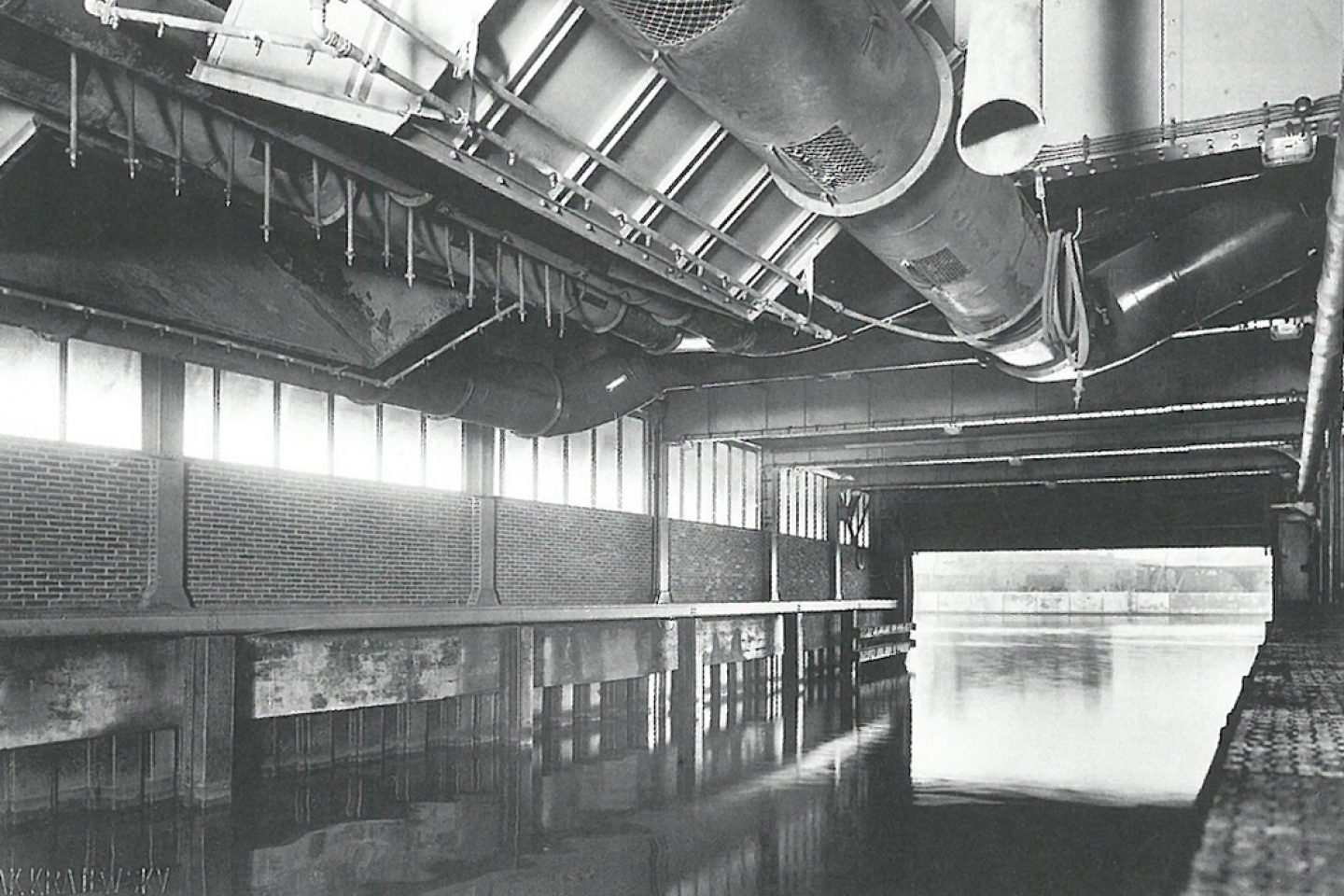

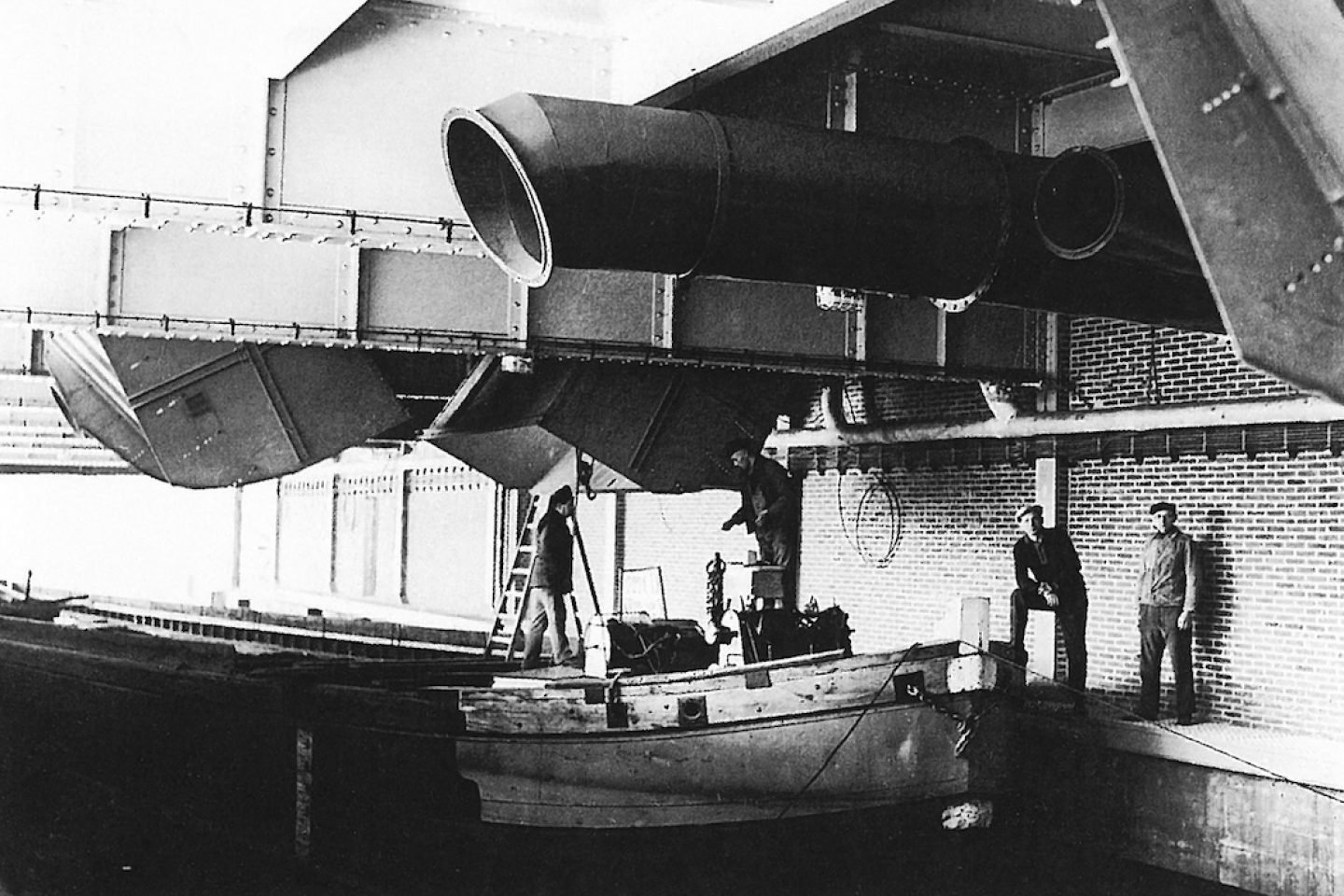

Jan Kleihues: “A building like this is unique. This has to do with the time it was built, the architecture and its function. The function of the building was that garbage, which in the past largely consisted of furnace ash, was carried up this flat ramp in horse-drawn carts. This large ramp was built so that the carts then could not only go backwards, but could also move forward. The interesting thing is that the whole building stands in the water. Downstairs there is a huge water garage where barges once docked. In the soil, there were pockets through which the debris has been tilted into the vessels. Then the ships went out to Brandenburg and had it dumped somewhere – though I’m not quite sure where exactly.

“The interesting thing is that the whole building stands in the water. Downstairs there is a huge water garage where barges once docked.” But the building only existed briefly in that capacity. It then stood empty for a long time, but was still being heated at the time when West Berlin was still hanging onto the financial drip of Germany. When we acquired the building in 1988, it was still in good condition, but hadn’t been used for a long time. There was some kind of application procedure where one had to pitch the best approach and we said from the beginning that we wanted to set up an office. That’s what my father did, since I was still studying at that time. At that point, I had my office in East Berlin located on Max-Beer-Straße, and my father and I only came together in 1996.

How did you convert the building into an office?

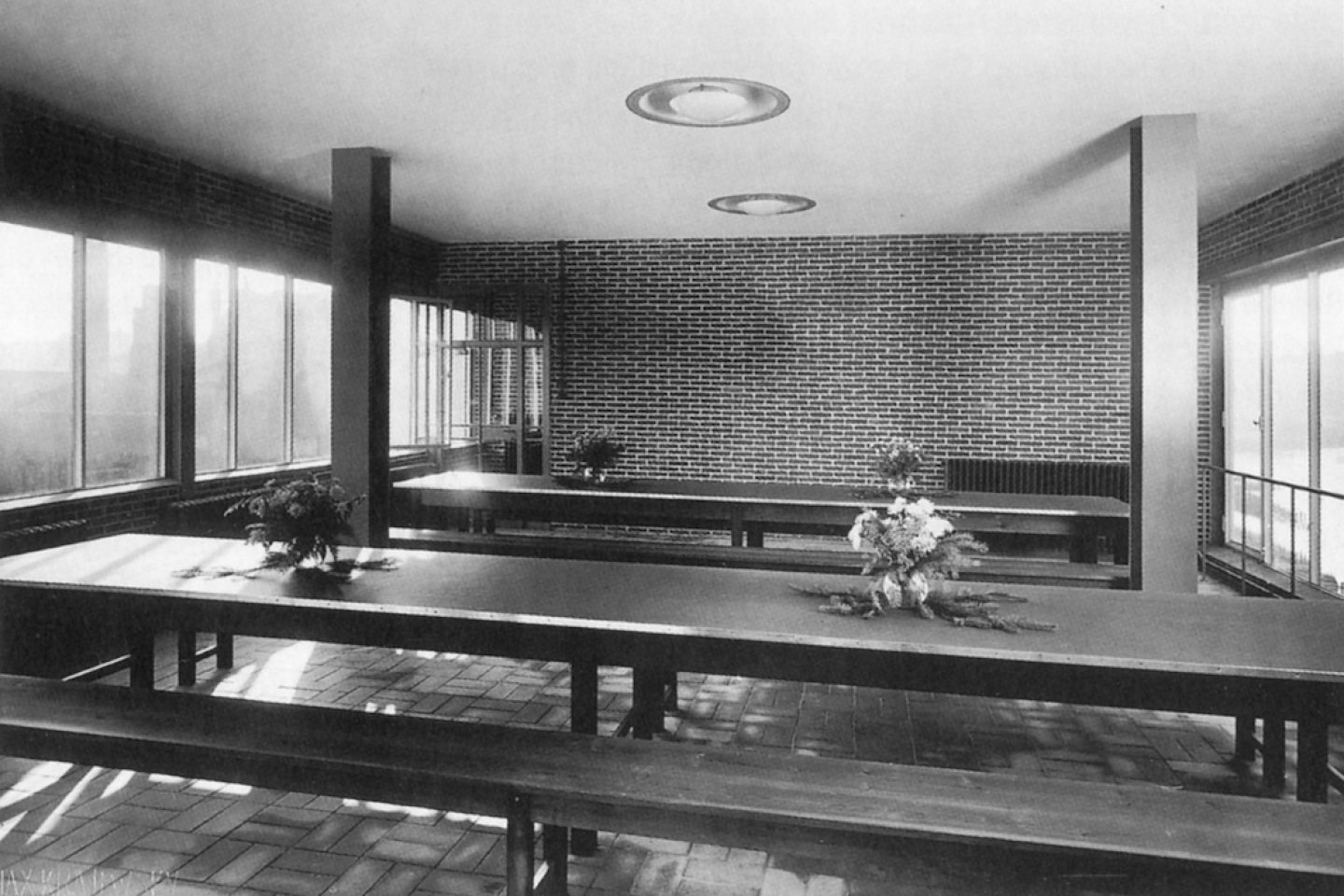

Jan Kleihues: “The problem is that this building was never intended to be used as an office – instead, it always had an industrial character. The hall wasn’t meant to protect anyone from the rain, but instead protect the neighbourhood. When you put the ash into the barges downstairs, it created a huge cloud of dust, which was then be placed on the adjacent land. That’s why you also had the gates built all around the building, which could be closed during the bulk operation.”

"This hall has the physical properties of a tent. That is, in winter, it is not quite as cold as it is outside, and during summer, it’s even warmer."

“The problem is that this building was never intended to be used as an office – instead, it always had an industrial character.” “The side windows, for example, were essentially very thin wire panes of glass that didn’t meet the requirements of thermal insulation nowadays. So we replaced them with relatively heavy insulating glass windows instead. Of course, you want to maintain the character of a building, which is why there are these C-shaped profiles. Before they were put in, there were just very flat profiles that were not strong enough. Now, we have these C-profiles, which cast a shadow. The other issue is that there were clinker walls. During the renovation, we padded the clinker walls with insulation and then another plasterboard wall on top. Since the ceiling is also something special of course, there is insulation on the roof too. We then also have 10 cm-thick insulation for the floor heating.”

How would you describe your architectural philosophy?

“We have no architectural label or signature like Frank Gehry, for example.”Jan Kleihues: “I would describe it as ‘rational modernity’ or ‘modern rationalism’ – whatever you want to call it. However, this now sounds like it describes a style, and I think that’s not the question at hand. If one takes a look at our buildings – this is not necessarily intentional, but instead a natural result of our approach – then the building, down to the smallest detail, is not necessarily recognizable as a building by Kleihues + Kleihues. We have no architectural label or signature like Frank Gehry, for example. I always use this example because you can always immediately recognize the buildings of Gehry, except for the house on Pariser Platz. That’s not our goal. Our goal is to integrate into the urban context, to develop it and to improve it at best. Therefore, the rational modernity is really just an attitude, but doesn’t necessarily follow a style. That is, when we consider the scale, the proportions and so on, it is really not about being flashy, but to remain relatively moderate in the background. For us, the issue of the city is very important and therefore, we always think about the overall context before we consider the specific building.”

"Our goal is to integrate into the urban context, to develop it and to improve it at best."

How do you typically approach a new project?

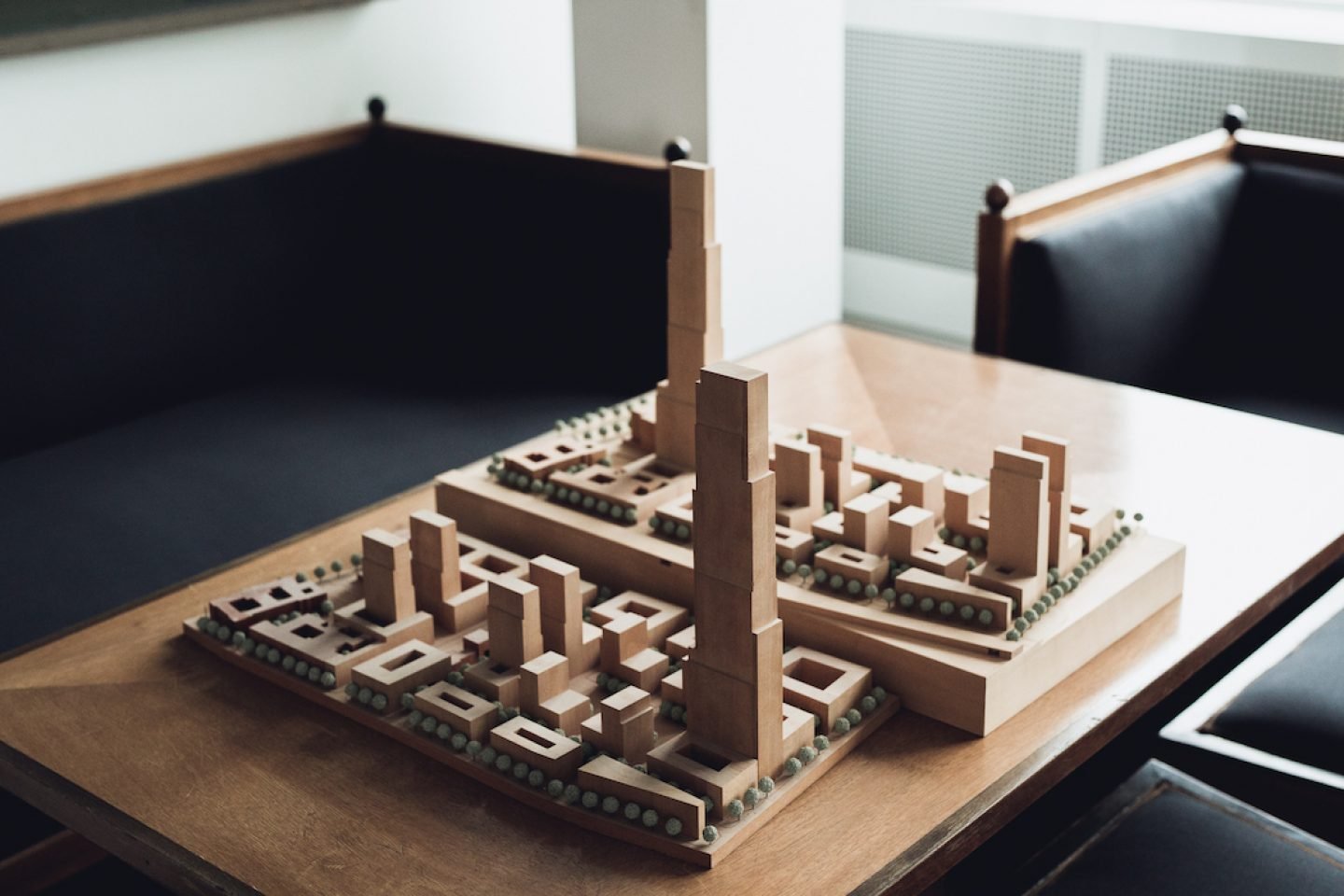

Jan Kleihues: “If I could, I would now give a lecture and in this lecture, I would show pictures. I would first show three images from three different models –planimetry, stereometry and physiognomy. Planimetry is the two-dimensional layout of the city. It’s all about a city’s structure, – ‘the fabric of the city’ – including building lines, roads and paths. How do I integrate myself into this city, and how do I develop the self-image of this city further? The second part, the stereometry, is just the three-dimensionality of what I have previously defined as two-dimensional. It’s again a matter of looking at the surrounding area. Are there high or low buildings or any buildings that have solitary character? And then there’s the physiognomy. This is the character, the face of the building.

"By the way, all architects claim to be timeless, but only we can really make it. [laughs]"

““We want our buildings to be just as relevant in 40 or 60 years’ time.” “We don’t do anything just because it’s in fashion, and we don’t pander to trends. We want our buildings to be just as relevant in 40 or 60 years’ time. If you now take planimetry, stereometry and physiognomy and break them down in terms of how we work, we will first look at the site and the surrounding area. We then take a look at what’s typical of the neighborhood. Next, we take a closer look at the buildings; their proportions, the window area proportion and materiality, and then we try to develop the design further with our buildings. Sometimes you can then also set accents that maybe also allow a look into the future – for example, how you can continue to build if the adjacent property is not yet occupied.”

What was, for example, the inspiration behind the glass roof of Galeria Kaufhof?

“A good house can only be as good as the combination of architect and client.”Jan Kleihues: “A good house can only be as good as the combination of architect and client. You can be the best architect in the world, but if you have a client who is ignorant or not interested in the matter, then the chances that the building will be good are relatively poor. You can see when looking at the structures themselves when the builder himself and not a manager has worked together with the architect on the project. Which was the case at Galeria Kaufhof at Alexanderplatz. That’s not a new building, it’s actually still the existing department store from the GDR. For its renovation, we had to build all the time without the store being closed. We were then of the opinion that the stairwell could be enlarged as well, giving the whole building a tremendous quality. As for the glass roof – usually a glass roof has to do with, well, glass. But especially in winter, the time when most things are sold, it gets dark relatively early and then these glass roofs are simply dark. But you want the exact opposite to happen. You want to spotlight them, and that is why we have developed this structure for Galeria Kaufhof. First, it’s a structure that evolves from the vertical supports and then merges into the roof. Second, we have a lot of projection space, that is, the panes of glass are vertically and are only set back and everything else is white. You can spotlight it perfectly, especially during the dark winter months. So the roof illuminates. And then it’s also a super exciting structure in terms of geometry, nothing sensational, just quite banal geometrical shapes.”

“The essence of this project is, of course, security against physical terrorist attacks and against foreign intelligence interception.”A current project of yours is the headquarters of the ‘BND’ Federal Intelligence Service in Berlin. How are you going about approaching such a project?

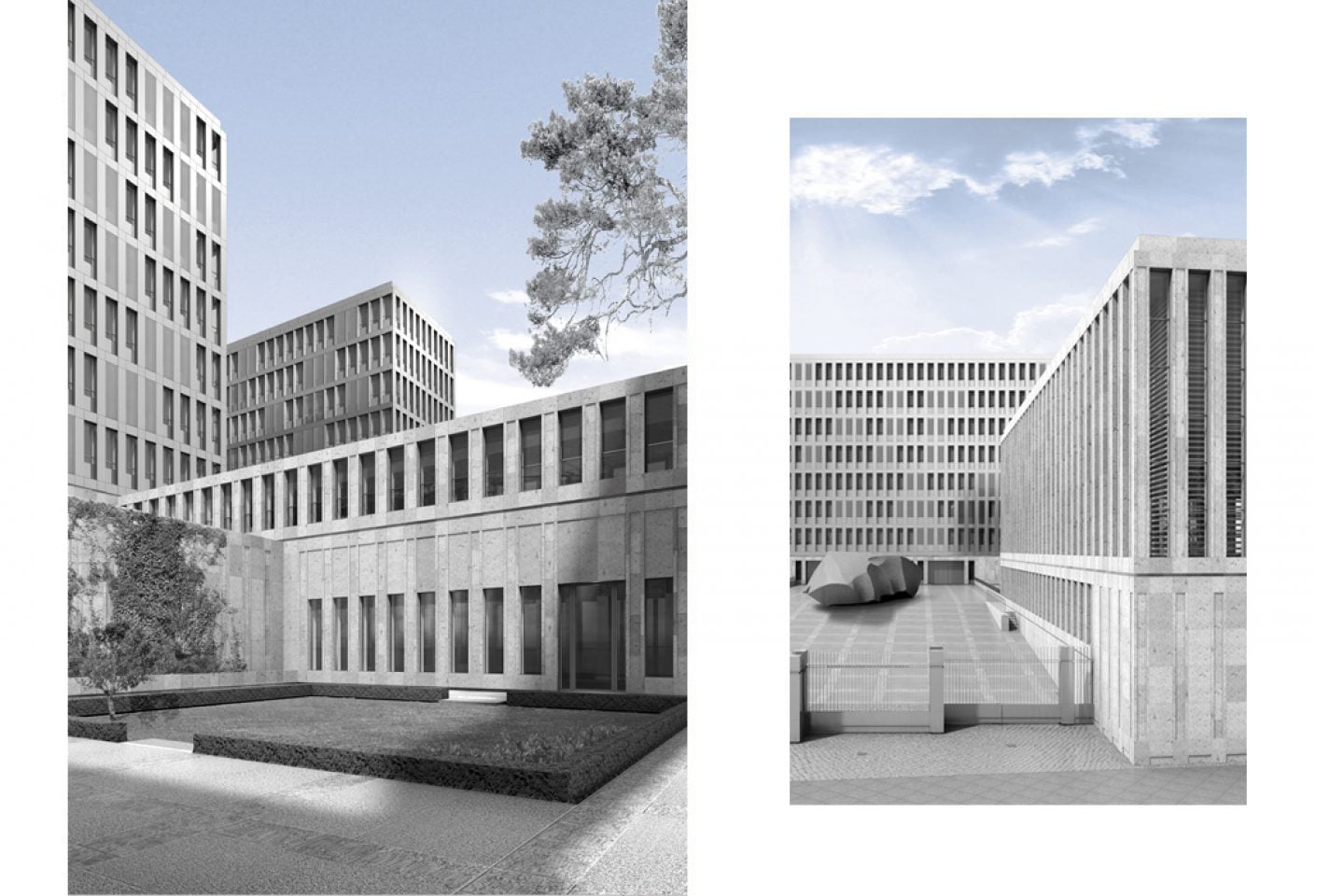

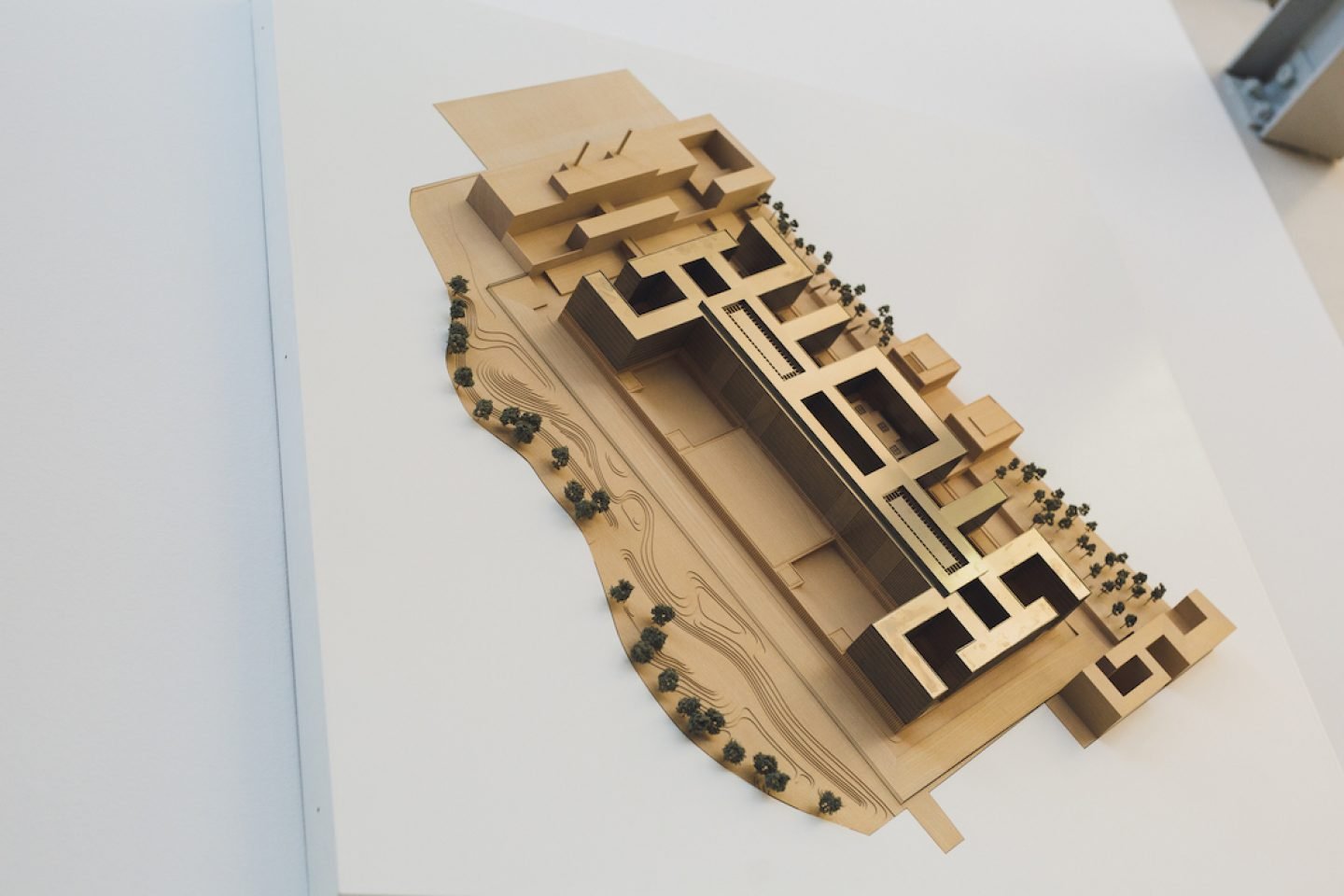

Jan Kleihues: “When I first heard that you can apply for this project, it was immediately clear to me that this has something to do with James Bond. [laughs] The essence of this project is, of course, security against physical terrorist attacks and against foreign intelligence interception. For these reasons, this building had to stand 30 meters away from the road. For us this was obviously a huge problem, because we really wanted to continue the building line. The other issue is that the function of this building is extremely important. This building has to respond immediately to global political developments, so certain departments need to shrink very quickly and other departments must be able to grow very fast.

“When I first heard that you can apply for this project, it was immediately clear to me that this has something to do with James Bond. [laughs]”Normally, we would have said, we’ll take the urban structure and scale it to perhaps build a small village. But that didn’t work because in this case, the vertical circulation has to work just as fast as the horizontal. The other issue is the visibility of terror. This building has a five-meter high pedestal, which is impact-protected and bombproof, and this base has, of course, no windows. In no case did we want to have it visible from the street, because then it would represent precisely these prejudices that people already has against the BND anyway. So we had the whole building set in a pit, with some kind of water castle setting the base in a sink, and on this base the buildings now stand. Now, when you drive along Chauseestraße, you see nothing. The base is hidden. It’s just like you’re driving past a normal building.”

"Nevertheless, we did not want to hide the BND in and of itself. The BND has an important function and we thought the building should have a confident look."

“Therefore, there are, for example, two gatehouses, which will also be seen on TV when the BND is reported on. Then there are 14 000 windows, all of which are identical. Now, one can say that this monotony is totally boring. But there are two ways of looking at things. On the one hand, when you walk directly along the walls, you can touch the brick and you can touch the railing. Then there is the view of the building from afar. That is the structure and material as well as the cubature. It was important to us that the cubature of the building was brought to the fore.

Unfortunately, the building is not accessible to the public, but inside, we aimed to design an open structure. There are three huge atriums which serve as central meeting places. There is the vertical connection with the usual elevators, but there is also a set of castle-like stairs. And then, of course, we have the rapid variability of the individual department sizes.”

You studied architecture in Berlin in the 1980s. How do you see Berlin’s future in terms of urban development?

Jan Kleihues: “So far, I’m very satisfied. Although many complain about it. I am firmly convinced that you can destroy a city with the wrong urban planning, but not with the wrong architecture. Either the architecture is good, then it stays. Or it is bad, then it is demolished and it is built something new. But if I take, let’s say, an uncontrolled sprawl – and as a negative example, I am now taking London – then one is really going to destroy this city. I hope that in this city – with such intact urban structures like Charlottenburg, Spandau suburb or the Scheunenviertel – one will still continue to handle it so carefully and gently, filling the gaps while maintaining a certain consistency.

"Berlin still has very much space and still a lot of potential, but we have to be careful."

Due to the refugee crisis, there is now a push from senator for city development Geisel, who argues that Berlin’s urban development should not be so narrowly defined anymore, with which I also agree to some extent. But you must also be careful to not open the floodgates to proliferation and uncontrolled growth. Now, one must also say that we slowly get into a situation where you can start talking about lack of housing. If we are talking about lack of housing, we do not even know what is already going on in Munich, let alone in London or Paris. We are still endlessly far away from that. Berlin still has endless amounts of potential of urban densification, since there are endless amounts of brownfield sites.”

The interview was edited and condensed · Photography by Ana Santl · Historical images © StADKPB · Project images © Stefan Müller, Achim Kleuker, Stefan Lotz