Beyond The Frame With Broomberg & Chanarin

- Words

- Anna Dorothea Ker

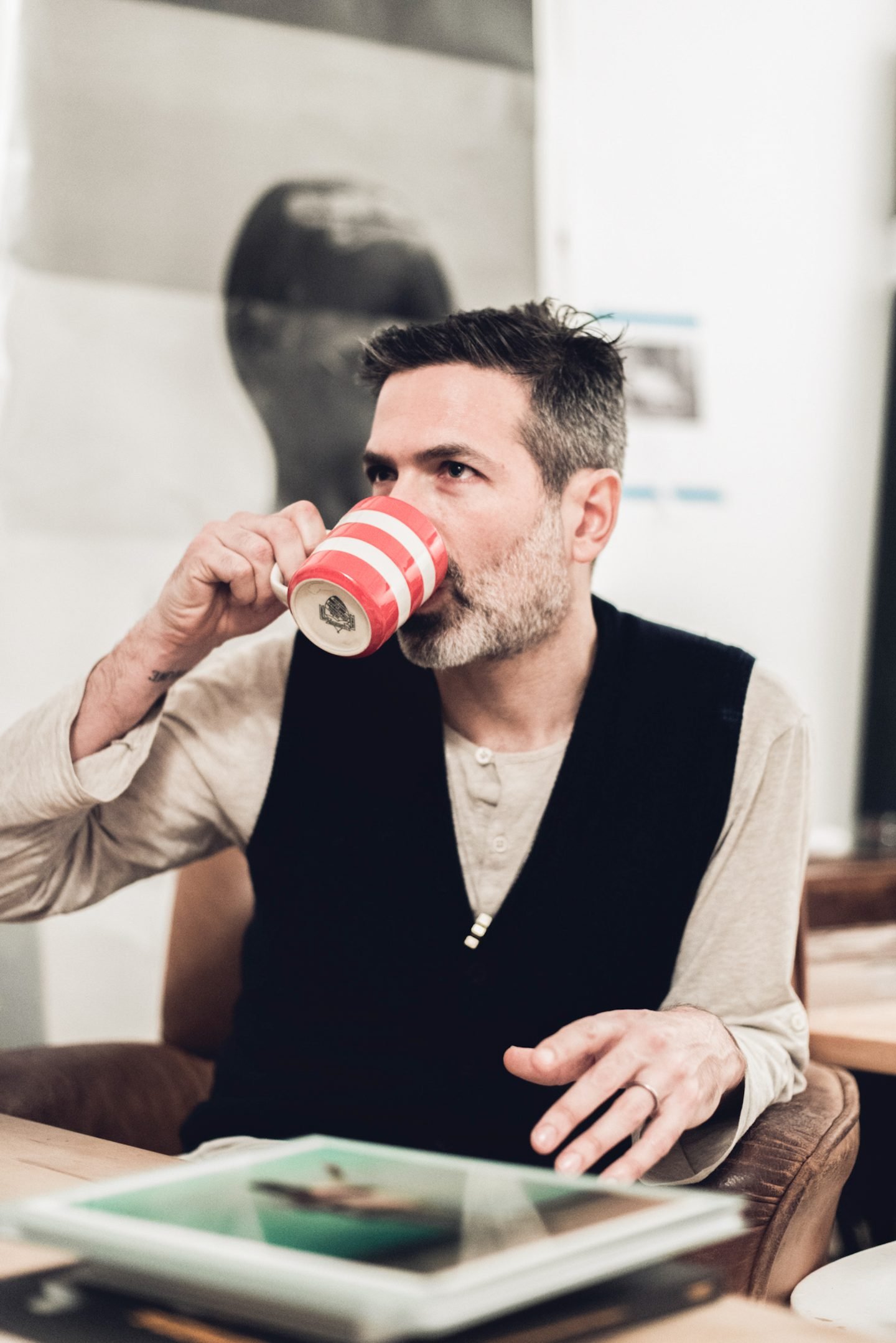

One blustery Spring day, in collaboration with C/O Berlin, we paid a visit to the then-brand new East London studio of the artist duo Broomberg & Chanarin.

Broomberg & Chanarin go beyond the frame to deconstruct the traditional tenets of the photograph.Renowned for their conceptual approach to the image and interrogation of the photographic process, Broomberg & Chanarin’s aesthetically varied body of work is tied together by a cohesive approach: One that Israeli intellectual Eyal Weizman describes as ‘finding the source code of photography’. Whether their attention is turned to Freud’s couch or surveillance cameras, the artists apply a sceptical approach to image creation and reproduction, going beyond the frame to deconstruct the traditional tenets of the photograph.

Over a cup of tea we talked to Adam Broomberg about the duo’s current projects, working without ownership and drawing inspiration from meditation. After Oliver Chanarin joined us for a few photos, we left feeling challenged, inspired and excited for the duo’s upcoming show at C/O Berlin, ‘Don‘t Start With The Good Old Things But The Bad New Ones’, opening 29 September 2016. The exhibition will be part of C/O’s ‘Thinking about Photography’ series, a new format for Berlin that places a deliberate focus on new trends in contemporary photography.

You’ve recently moved into a new studio space. How did you select it, and which interior elements are most important to you in your photographic practice?

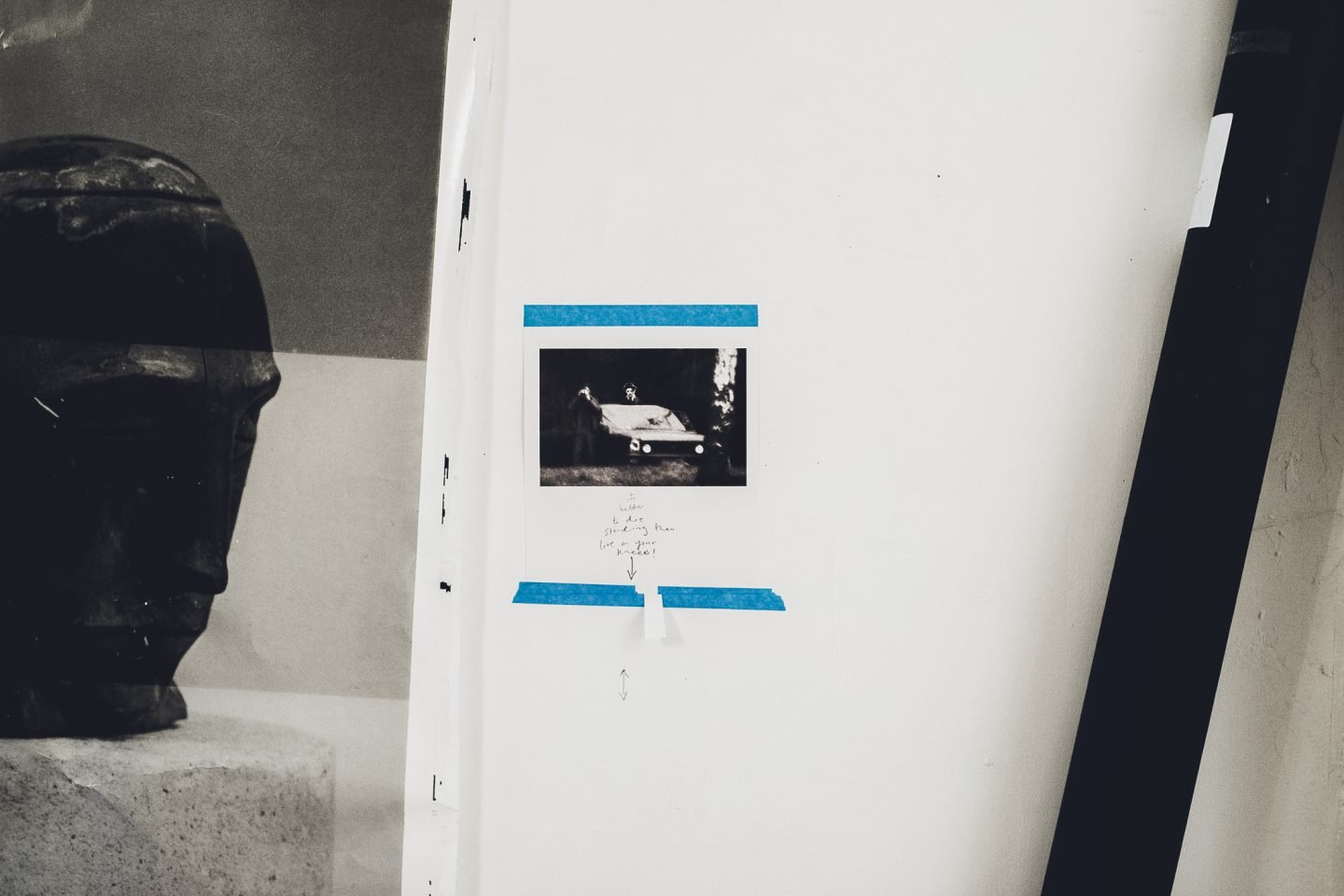

Natural light, space, character… [laughs]. Why did we move here? Because we couldn’t afford the last studio. We wouldn’t be in a sealed space with no windows out of choice. Saying that, Space Studios is a remarkable organization. It’s one of the last subsidized artist spaces, so the whole complex here is occupied by artists – and this is in East London, with its crazy property prices. For us, the studio changes shape according to the project – some are very hands-on, very tactile, and involve a lot of making. At the moment we’re in a very different space, we’re not in production – we’re researching, thinking through a number of projects. So it’s a very fluid space for us, it’s not stable.

For those less familiar with your work, how would you define the ‘red thread’ running through your diverse photographic practice?

With each project our concerns – for good or for bad – remain the same. Somebody said to us recently: ‘The problem with your work is you’ve got no one style’. We’ve heard that quite often. It makes us a kind of commercial disaster, but I think there’s real stability and consistency in the way that we interrogate what we’re approaching. I think it’s essential that we use different aesthetic strategies, because to use the same one would be acting unfaithfully to the idea. It’s difficult, in some ways, because we didn’t go into this whole thing knowing exactly what we wanted to do. It’s been a learning curve that we’ve unfortunately imposed on the public [laughs]. These strategies do vary between Olly and I, but our intentions are the same. We did quite an amazing interview with Eyal Weizman, a discussion that became the text for ‘Spirit Is A Bone‘, and he said something quite lovely and really flattering: that we try to get to the DNA of photography, the source code of photography, That really made sense to us.

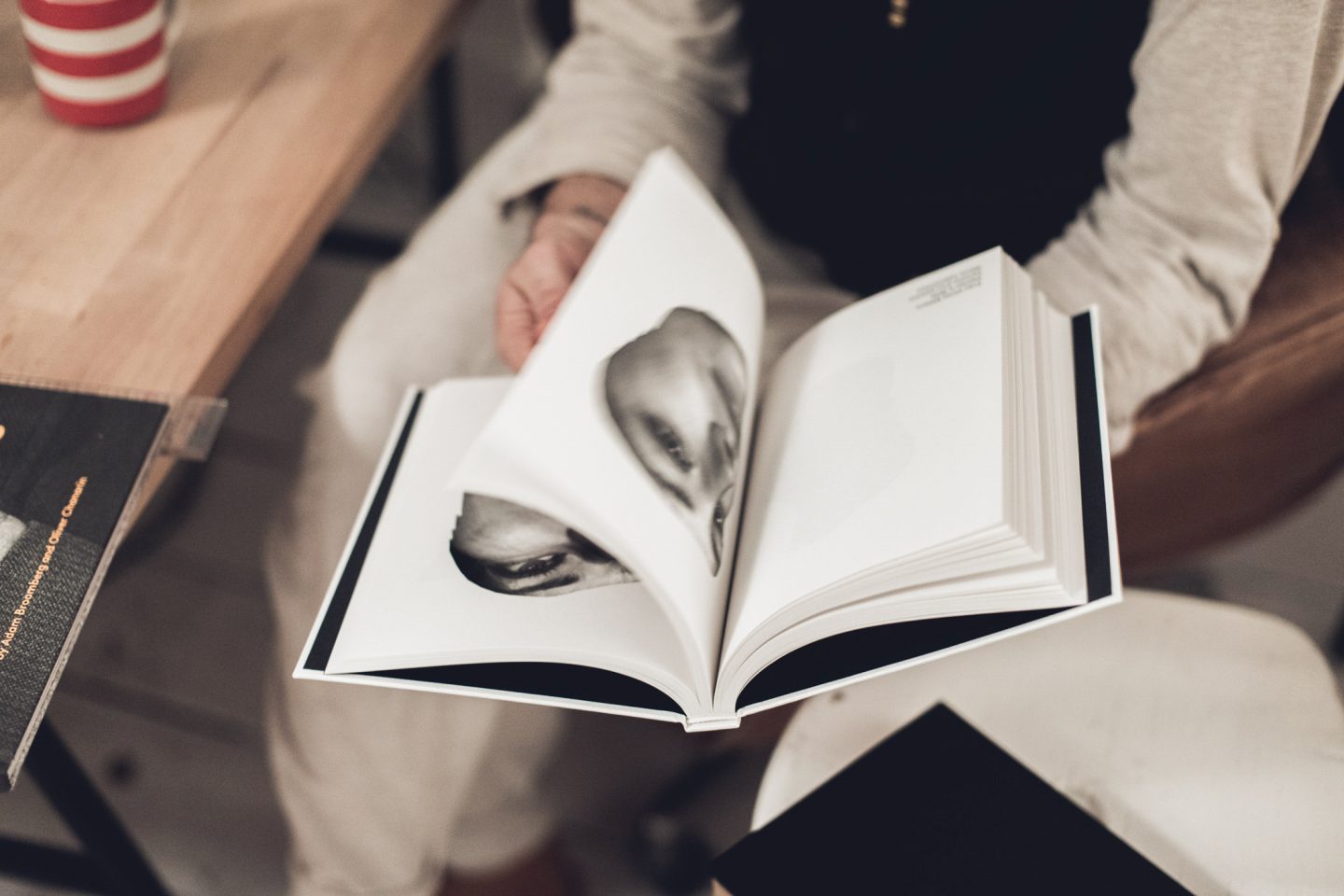

This book was made using surveillance technology developed by the Russians, which is being rolled out around the world. The images it contains are ostensibly portraits, but they were created by these machines using a process called ‘non-collaborative photography’. The notion of the accident and the notion of control are very important to us. This project contradicts a central tenet of traditional photography: that the person behind the camera is ultimately and absolutely in control – of the frame, of the composition, everything up until the print. That’s what gives it its value: the authenticity and integrity of this kind of ‘genius’ vision. ‘Spirit’ is quite the opposite. We don’t have authorship – because we’re collaborating with the people who are creating something for us – and often we leave it up to accident. The fact that there are two of us means we often talk about our work in anonymous terms – neither of us own it. I think those things have pretty much remained consistent. There’s a sense of mistrust in our interrogation of the image. I’ve never been in love with photography, and I think that’s a healthy thing, I’ve never been enamoured by the craft of it, which can overwhelm a critical sense. I don’t want to be arrogant and align us with conceptual artists, but the notion of the idea being more primary than the outcome is quite an interesting thing. It removes any sense of commitment to one aesthetic strategy, and that’s important to us.

Another recent project took place at the Freud Museum – his former home. We were fascinated by the famous couch that’s is still there in the study, covered by this beautiful Qashqa’i rug – thinking of all the patients that had lain on it, and the minute physical traces they would have left. We got a forensic team to come in and examine it. They took hairs, fibers, dust – everything they could find – and did an analysis as if it were a crime scene. We took these super magnified images of their scientific findings (which were lurid rainbow colours) and we turned them from a photographic image back into a woven tapestry. We like to not be in control of the result of a project, certainly aesthetically. We had no control over the outcome; in fact, it was so ugly that Olly called it a giant beach towel. But that’s not important. What’s important it that someone else was in that position of power – it’s about the performance and the collaboration. In many ways it’s like a project called ‘The Day Nobody Died’ that we did in Helmand Province, in Afghanistan. We exposed sections of photographic paper to light each time an event happened that would be considered newsworthy. Again, we weren’t in control, it was the sun and heat that determined the aesthetic outcome. And I think that’s kind of consistent for us.

Your background lies in sociology. How did you make your foray into photography, both individually and as an artistic duo?

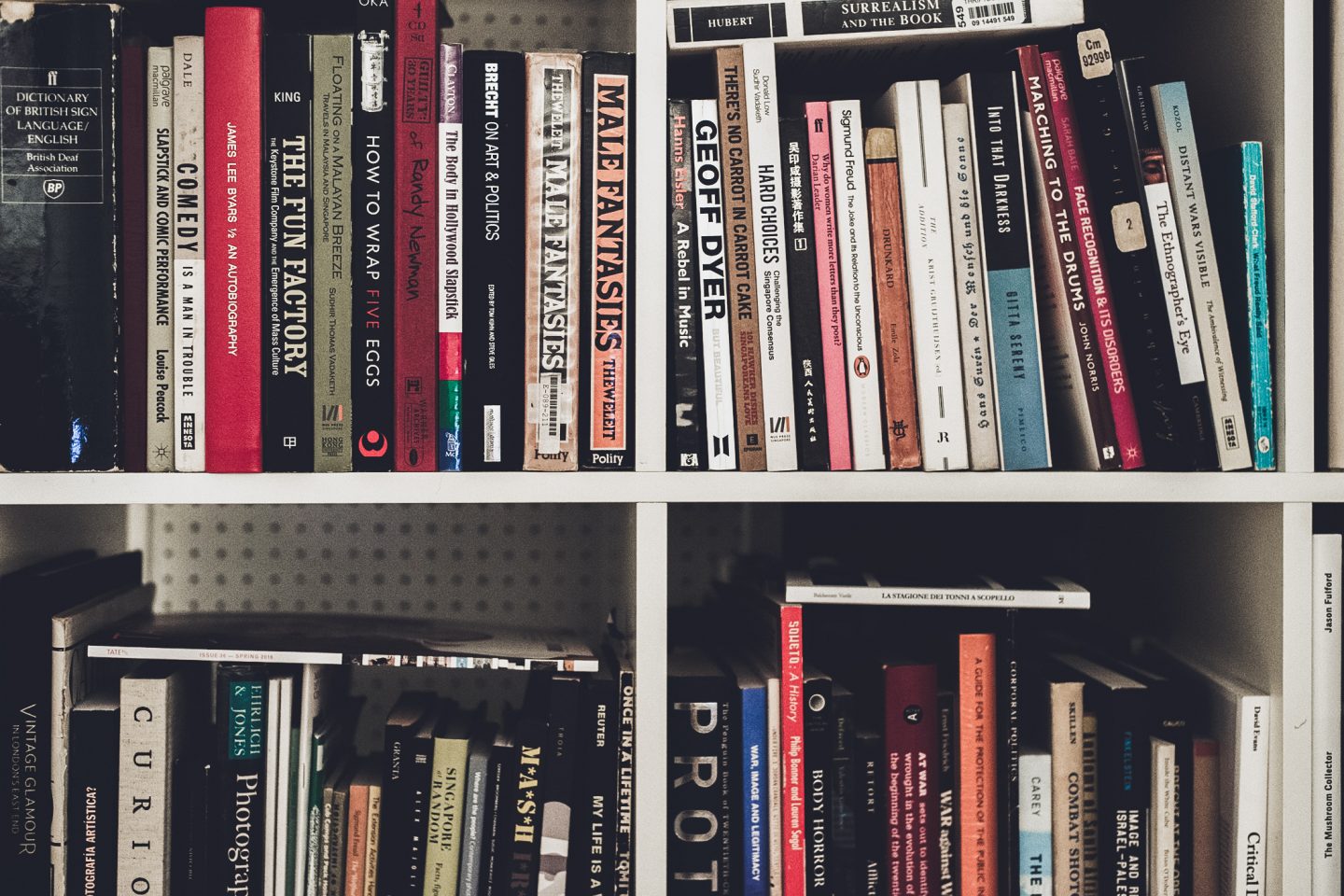

I mean, I was 18, living in South Africa, in the 1980s. My sociology professor was assassinated. It was a very powerful time, very politicised. I think you had to be informed, and have a political conviction on both sides. So that was hugely informative for me, more than any formal education. In saying that, because of the cultural boycotts, we were really isolated and cut off, and I think that served a purpose as well – not being encumbered. I speak to people my age that went into art school, and there’s a massive legacy of the history of art, which I just didn’t know. That’s allowed us to have courage to do silly things. It was really a series of accidents. We started off as friends, and started working together on Colors magazine – the one that Benetton used to fund – and then we just bumbled into it. Neither of us are very reflective human beings, and we didn’t sit down and strategize – it was really an accident that suddenly started to gain traction. Neither of us were formally educated in art, we’re much more interested in what’s going on in the world than what’s going on in the art world. We’re not artists’ artists. I think with the books particularly – we’ve made 15 or 16 – they function as works because they interrogate their own form, a little bit. They don’t follow standard operating procedures in terms of a how a book functions.

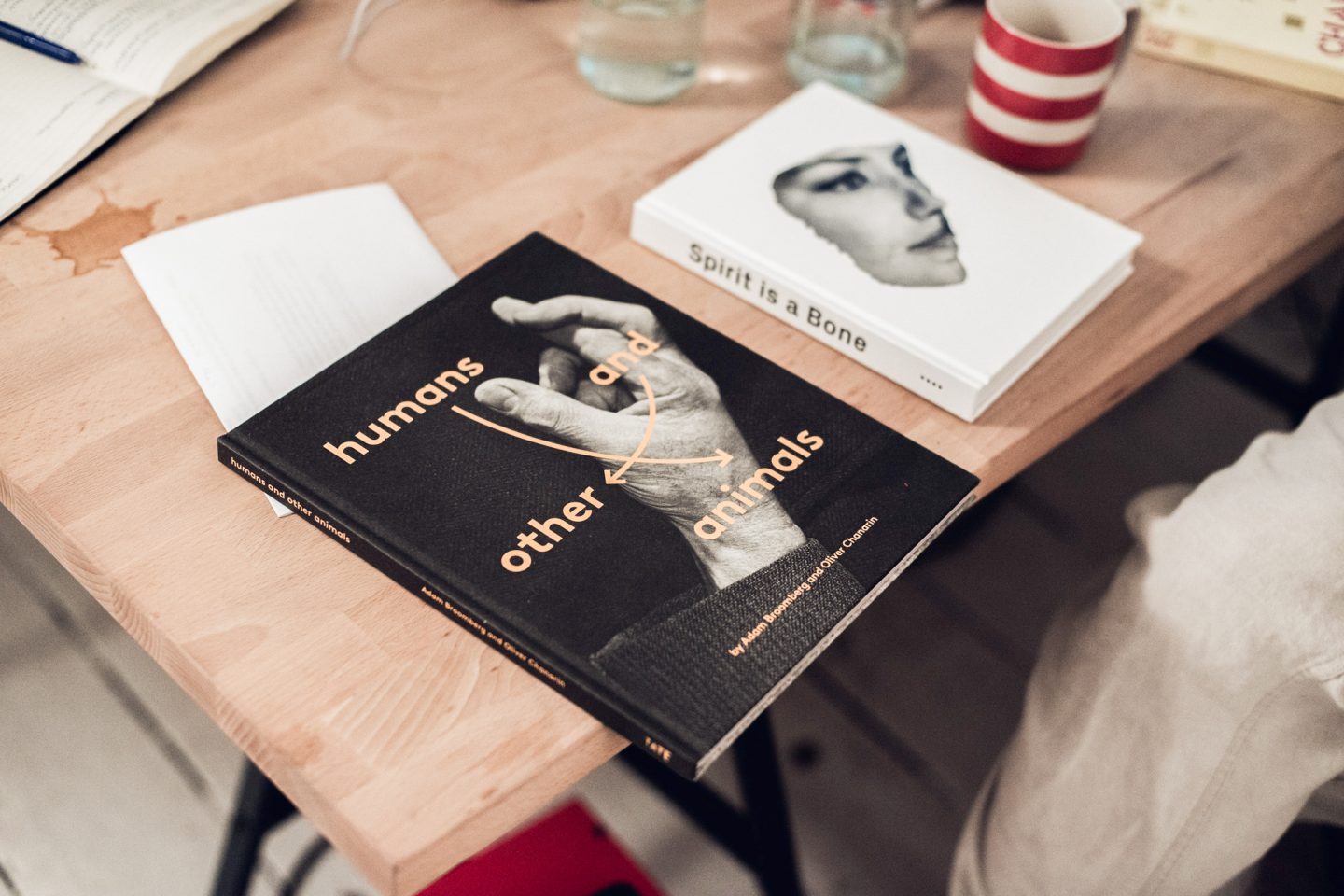

Two of your books take centre stage at your upcoming exhibition at C/O Berlin this September. Can you elaborate on the stories behind them?

This [picks up ‘War Primer 2’] is a prime example of how to interrogate the medium – what does this object mean? Symbolically, politically, everything. As is Spirit – it’s revolting, a really creepy experience. The fact is, you don’t discover anything more from each page – that is the object. You can’t unpack it; it’s almost as if something just emanates from it. So I do think our books – some more successfully than others – interrogate the notion of what it means to be a book.

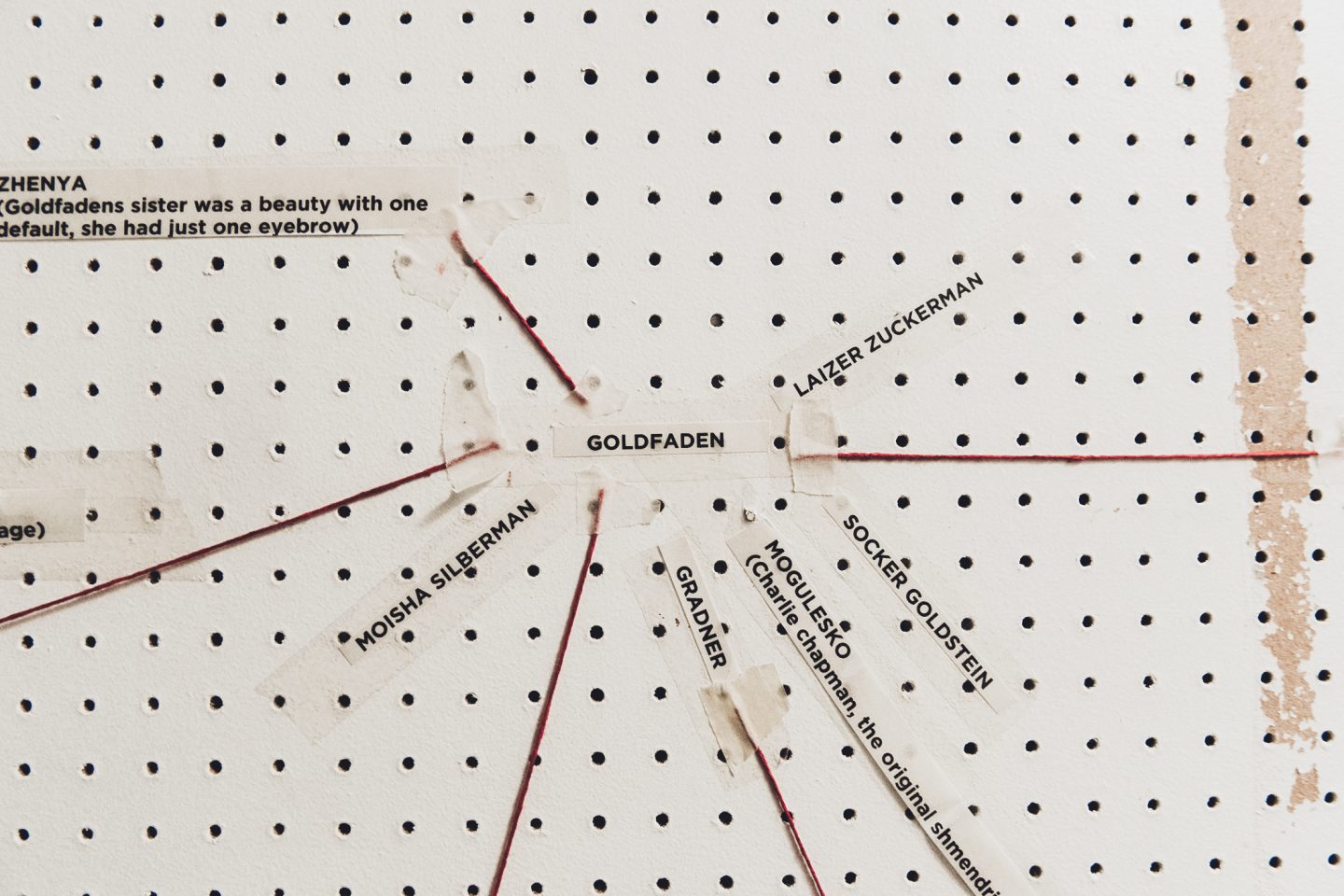

With ‘Holy Bible‘, its format belies its production – it appears to be a linear narrative, but we spent about 6 months to a year in the Archive of Modern Conflict, and then we spent months and months reading the whole Bible, underlining things that seemed interesting and relevant. The way we conceived it as an art work (Divine Violence) is an exploded form of the book, a massive collage that you can’t conceive in its traditional linear form. It’s a whole different experience. Photography has this pretense of trying to document everything, so we mined one of the most extensive archives in the world, the Archive of Modern Conflict – we had access to everything from Bikini Atoll to Curtis [Collection] images. It’s also such a remarkable place because it’s almost an anti-archive, it’s the underbelly of history – so it doesn’t just go for the main events, there are some amazing pictures of Nazi soldiers – maybe I can find you some – really intimate pictures of them, like two of them sleeping on a train. So it’s a kind of narrative that you would never normally have access to. This idea that these are young boys, sensual, intimate, and gentle with one another – we’ve only seen the machine-like, regimented automaton. And so it was really quite remarkable to have that access, and it seemed like the perfect way to approach this project. A whole other big thing of our work is the wrestling between words and images in every sense, not just literally – words can be a thought or a concept, and images can be projections. I think that tension runs right through all of our books. The exhibition form, Divine Violence, will be shown at C/O Berlin, alongside War Primer 2.

You’ve also been working on a German translation of your book ‘Humans and Other Animals’, an A-Z in sign language and photographs that explores how we interpret photographic images. Can you tell us more about this project?

I read this to my children, and as a story, it’s awful. But I did a few workshops with kids at a local school just yesterday and as a tool, it’s remarkably functional – it’s quite liberating to make something useful, an educational tool. This book doesn’t interrogate the children’s book genre – but there’s something amazing about the visual language of signing. It’s a fad to teach toddlers under the age of two to sign, whereas usually the language itself is totally ignored. Yesterday I was working with a lovely girl called Abi, who is a sign interpreter, and her mum is deaf. She was saying her mum – who is my age – had to sit on her hands for the first 15 years of her life, because up until relatively recently signing was illegal. Deaf people weren’t allowed to own property. There was a real threat perceived, because this language is such a very subtle, complex and personal one. We realized, when we started producing a German version, that not only does the written language change, but the signing is different too, so there has to be a full translation. For each book we make in a different language, Connor [The boy in the photos] has to learn the new signs, and he’s going to be older and older as we do every edition. Most people don’t know that signing isn’t universal. They’re trying to formulate a universal sign language, but even in the suburbs of London, people have different ways of speaking, you know?

From where or whom have you been drawing inspiration recently?

Meditation [laughs]. Seriously, I’ve been spending a lot of time doing that. That’s been remarkable… let me think. I think I’ve been reading quite a bit about that period from 1966 about conceptual art, when the idea of art as an object kind of dematerialized. In 1969, Baldessari took 12 years of his work and cremated it. He made 6 little biscuits out of it, and he spoke of it as this great liberation – I mean, 12 years. It made me think about all the things we’re keeping down the hall in storage. Why are we keeping that? I’m quite attracted to this idea of getting rid of it, and that void. There are a lot of people who are making work about that – Lawrence Weiner is still making work about it, where it’s just transferred in words, and these words, for him, are sculptures.

I remember when Olly and I were really young, we met a good friend of Joseph Beuys, who took him to Scotland for the first time, and he took lots of pictures of the two of us. I asked him why he was taking pictures, and he said, well, because I’m an adherent of Beuys’ idea of social sculpture, which is that every interaction is an artwork. So I’m quite intrigued about the idea that it’s not about the creation of objects. A book is a lovely way to work through that. Luckily they never really garner the attention of the art world, because they can’t be commodified in the same way – they kind of slip underneath or above it. Also I think they’re threatened by the very real intimacy of the book, the way it changes each time you approach it. A book’s not a public event, which so much of artwork is. So actually when I think about it, I’m more comfortable being in the realm of the book than any other, even though I’d never consider myself a kind of bookmaker.

In an age where everyone is a photographer, how has the standard or criteria for what makes an exceptional photo shifted?

I think, for me, it’s always been about photographs that are aware of their own making. I mean, Lee Miller made just a couple of genius moments, and they were very performative. One is of course is of her and her lover taking photos of each other in Hitler’s bath. In fact, I’ve traced that bath, the actual bath, which is in the basement of The Academy of Fine Arts in Munich – I’m dying to track it down. So you’ve seen that photo of Miller in the bath, but never the one of her lover, right? And that’s funny, because that’s Lee Miller’s image. It’s interesting how history kind of coagulates and narrows down to a few iconic images. I recently got hold of those pictures, and I loved the performance of that: that’s performance in a photograph. There was another she took when she was on top of the pyramids, and it’s just a shadow of the pyramid, but also a self-portrait because she’s at the top of that pyramid. Those are two of the photographs that set off the consciousness of the medium, which I really love. Photography can’t help but have that; whether it’s the intention of the photographer or not, that’s not always there. That’s what makes it. I think our practice has almost been one of defiling images, or dissecting them. With ‘Afterlife’, we literally cut the photograph up with a scalpel. With ‘Holy Bible’, there’s no captioning, no authorship – Walker Evans’ Polaroids are in there, and you wouldn’t know. There’s kind of a lack of respect for the medium that I think is healthy. The fact is that the medium of photography has always changed so rapidly, always been in a state of flux. It’s about learning how to harness it and enjoy it.

"The fact is, the medium has always changed so rapidly. It’s actually about learning how to harness it and enjoy it. "

With thanks to C/O Berlin for making this interview possible.

All images © Owen Richards, created exclusively for iGNANT.