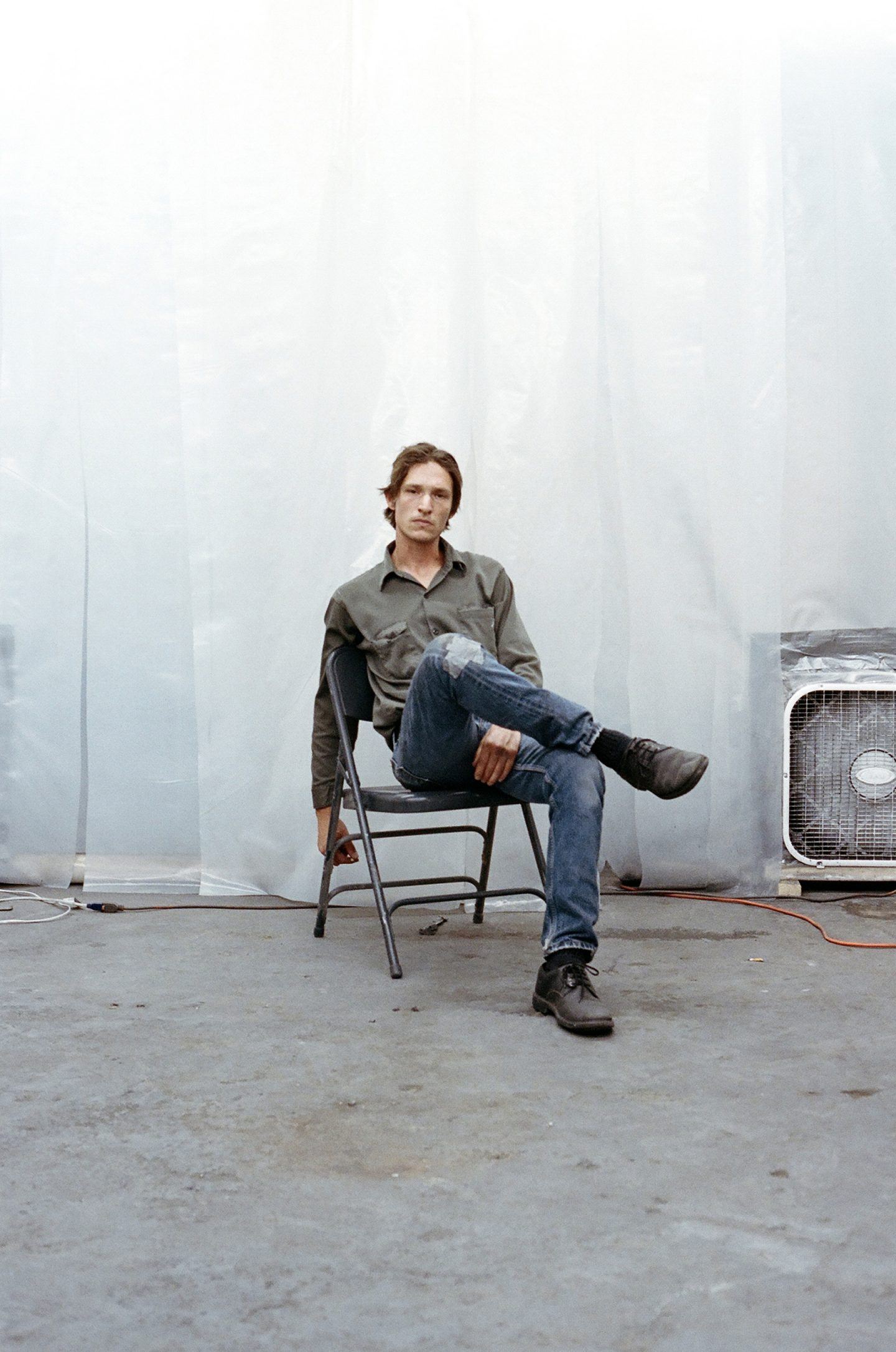

To Create Is To Destroy: In Conversation With Daniel Turner

- Name

- Daniel Turner

- Photographer

- Daniel Turner

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

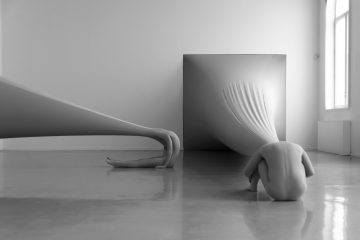

For American artist Daniel Turner, to create is to destroy. In his current alchemical solo exhibition on show at König London, he has used the material of a psychiatric facility to create five post-minimalist sculptures.

Having been institutionalized for both psychological and neurological conditions at various stages throughout his life, Turner’s choice of the WAMC psychiatric facility in North Carolina as material for this exhibition seems pertinent. Can an artist ever truly be free of their history? Whilst Turner’s work may seem obliquely drawn from his own experience, in conversation with IGNANT, he insists that these sculptures are not autobiographical, but instead the impersonal result of a chemical process that pays respect to materials and their origin.

For Turner, the elements that he works with carry a sociological, emotional and political weight, each equally considered as he recasts them as works of art. This phenomenological approach is interestingly tempered by his desire to separate himself from his creations: “The introduction of my hand would only suggest a painterly or pictorial approach towards form,” he explains, “therefore it’s important for me to remain removed.” As the show winds to a close, we spoke to Turner about his process-based practice, the lack of sentimentality with which he approaches his art, and how he found exhibiting in the former car park that houses König London.

Your work is often concerned with the transformation of materials and their “cumulative history”. How does this come into play in your current exhibition?

When I speak of cumulative history I’m referring to a succession of affects upon any given material, how place conditions material or site. The exhibition in London consists of five free standing aluminum and fiber forms, each of which was cast out of material extracted from WAMC Psychiatric Facility in North Carolina.

König London is housed within a car park, which has a lot of character and traces of past use. This, perhaps, presents a challenging setting to show your post-minimalist pieces. How was it to work within such a space?

The gallery itself is subterranean, therefore the setting was rather ideal, equally quiet and removed. While the forms are highly calibrated in their production, the position of each is guided solely through intuition.

Daniel Turner - König London

All images © Daniel Turner, courtesy of König London

The sculptures “bare no trace of hand”—yet they’re loaded with autobiographical value. How important is it for you, if at all, to remain seemingly removed from the artwork whilst expressing such personal experiences?

While I have been institutionalized for both mental and neurological conditions, I don’t see my sculptures as autobiographical or personal. The exterior finish of each form was developed out of a reductive process. Each of the five forms have been machined milled to reveal its material properties. The introduction of my hand would only suggest a painterly or pictorial approach towards form, therefore it’s important for me to remain removed.

You have been shortlisted for the Pinchuk Future Generation Art Prize for 2019, which will culminate in a group exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale. Can you talk us through this exhibition, and any other projects you are planning for the year ahead?

I’m currently working on three sculptures for The Pinchuk Art Center, each of which in direct response to The Vinnitsa Regional Psychoneurological Hospital in Vinnitsa, Ukraine. Founded in 1897, the active institution specializes in polyclinic medical care for psychiatry, neurology, and neurosurgery. I have identified, archived and recast one metric ton of the hospital’s steel bedding into two concentrated forms. Additional material extracted from the site has been distilled into a steel byproduct, which will be burnished directly into Pinchuk’s museum walls.

All images © Daniel Turner