Art As Resistance, Artist As Smuggler: In Conversation With Hector Prize Winner, Hiwa K

- Name

- Hiwa K

- Images

- Thomas Pirot

- Words

- Juliane Duft

For Hiwa K, whose name means hope in Kurdish, art is intimately bound to storytelling. His own biography interweaves with the tales of others in his exploration of interstitial spaces, ideas of belonging, and exchanges between cultures.

The new building of the Kunsthalle Mannheim mimics the strict grid of the city outside. Inside, the solo exhibition of the Kurdish-Iraqi—who fled to Germany when he was just 25—also draws lines between art and the outside world. Curated by Sebastian Baden, the show celebrates the 2019 Hector Prize, and shows major works from Hiwa K; including those previously exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery, the Venice Biennale 2015 and documenta14. Hiwa K’s works draw attention within the art world by finding bold, poetic and even humorous ways to tell stories about the global political crisis that we are all part of—blurring the lines between fiction, art and lived reality.

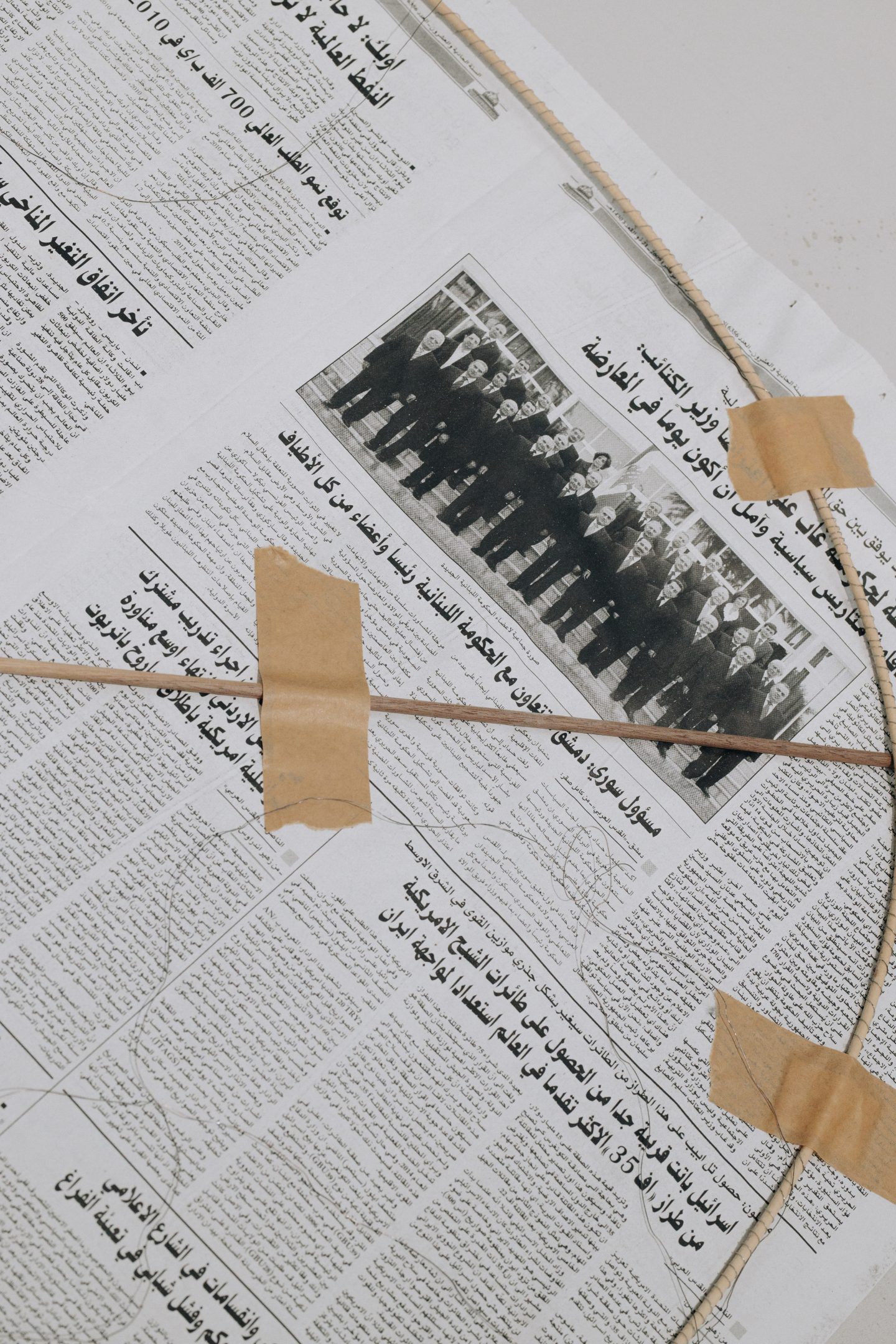

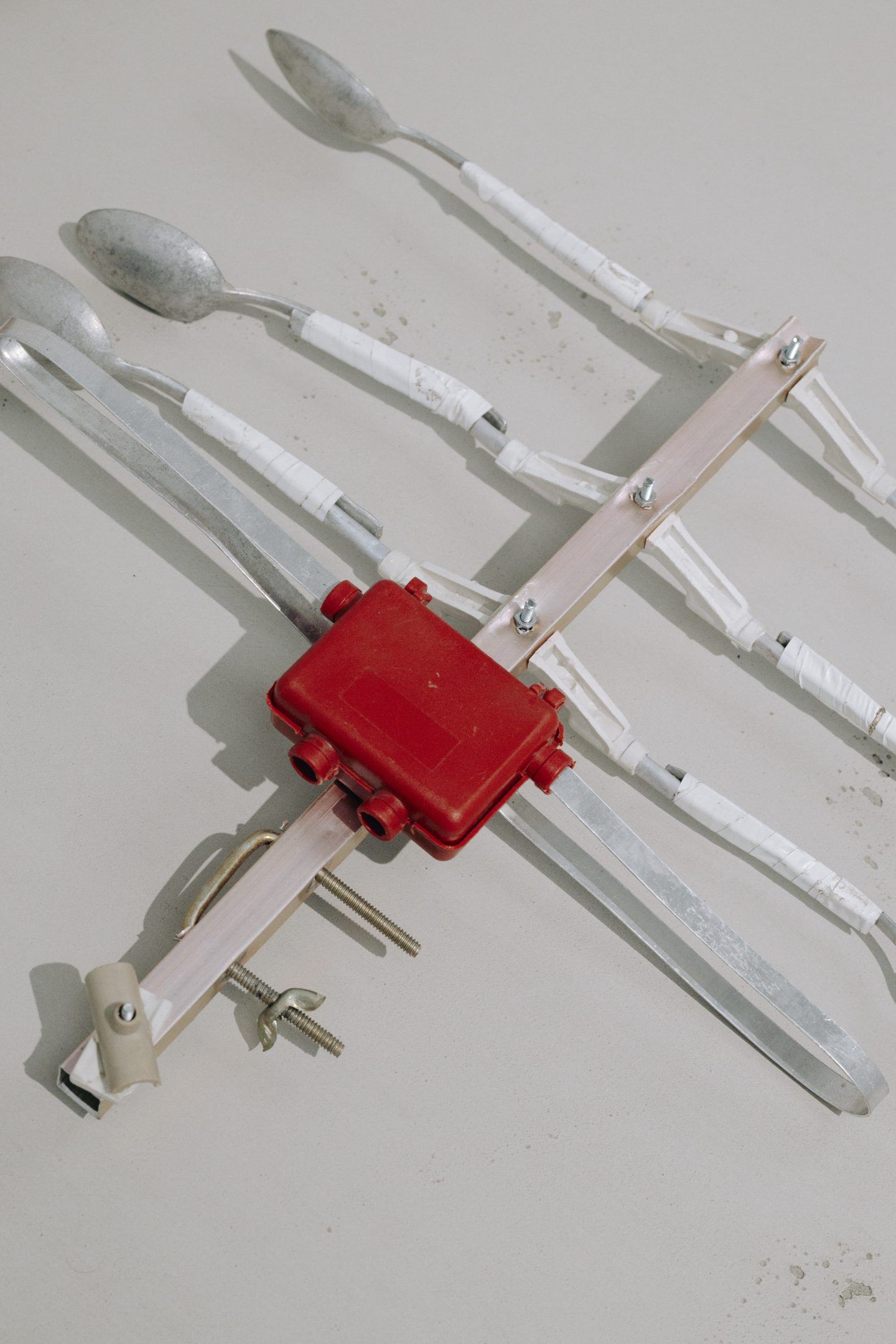

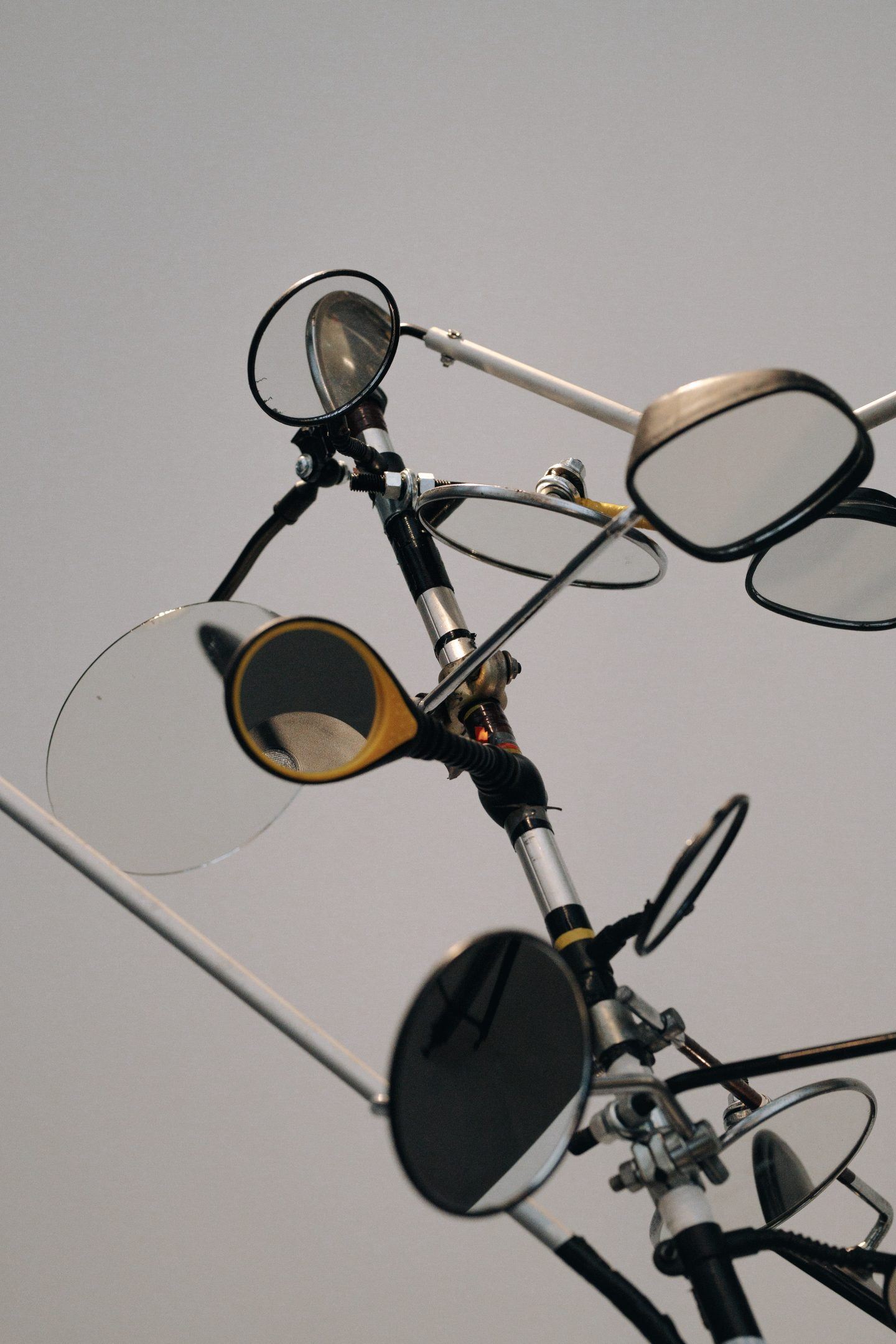

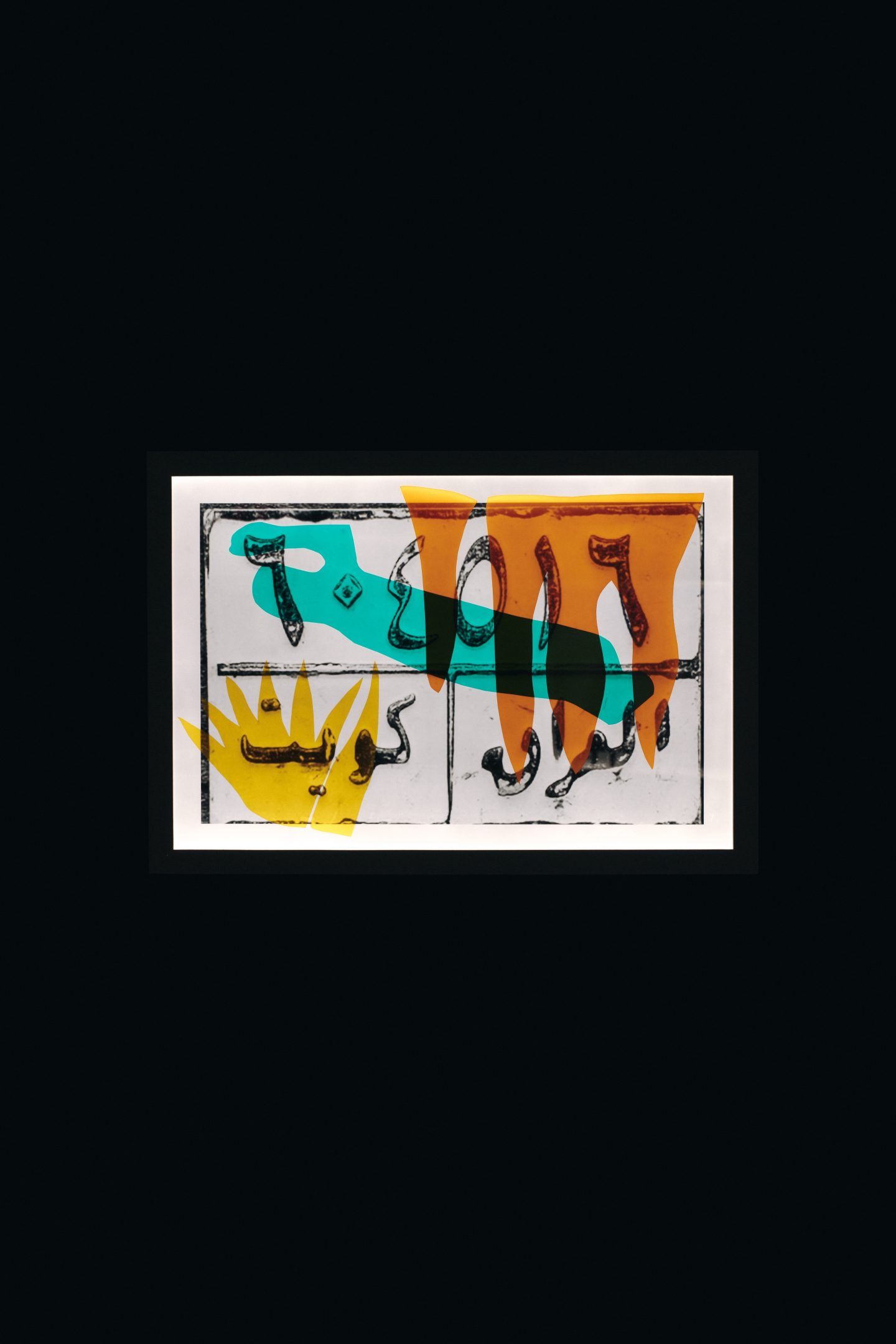

The first room in the exhibition shows his search for ways to communicate, both physically in his works as well as conceptually in his practice. In ‘Qatees’ (2009) he documented and collected oddly shaped antennas used for receiving military radio conversations in the Kurdish crisis area in Iraq. For ‘Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue)’ (2017), he built a strange device from a pole and many rear-view mirrors. In a video, he balances it on his nose, slowly making his way through a barren landscape while viewing his environment only through this strange prism. Between the thick white walls of the Kunsthalle, on a pedestal, the bizarrely twisted wire antennas and his kaleidoscope wand become beautifully fragile sculptures, but they still strongly point to the world outside.

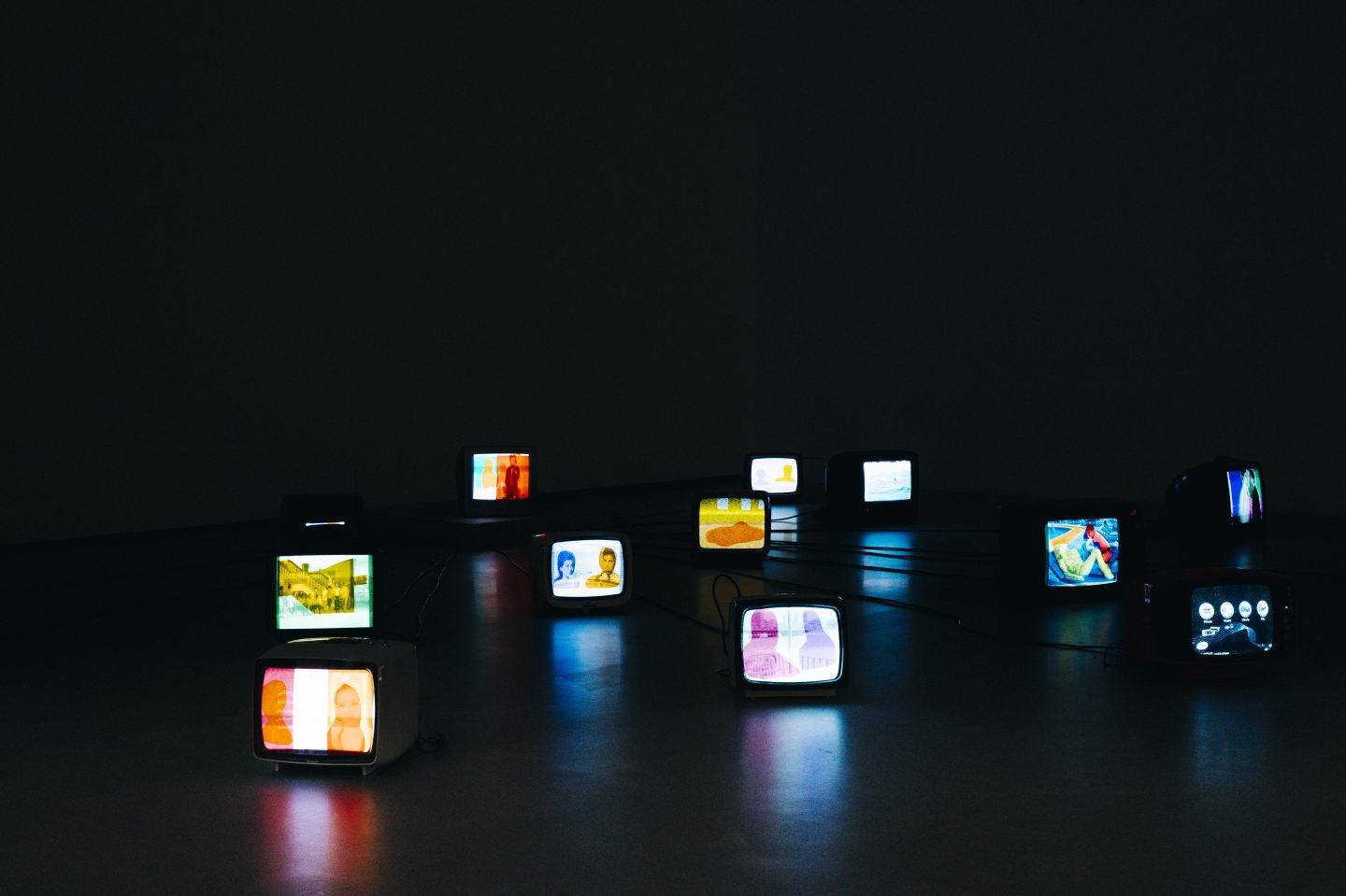

In ‘My Father’s Colour Period’ (2013), a group of 16 televisions sit flickering on the floor. Hiwa K has pasted their screens with foils; making the black and white images appear colored. They will play as such until the television tubes eventually run out, turning the screens to black forever. It was an idea inspired by his father—a man described by Hiwa K as an “ingenious rascal”—who introduced color television to his family this way in the late 1970s. It was a time when the Kurdish area of Iraq had limited access to such chromatic pleasures. As Hiwa K tells us, quoting Shunyamurti, “Comedy is the highest mode of art”. This belief seems to be one that he inherited from his father. In another video work, he walks through a Kurdish protest. While those around are attacked with tear gas, he plays the theme of the Spaghetti Western, ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ on a harmonica—in German, the title translates tragically to Play Me the Song of Death.

For Hiwa K, the “artist is a smuggler”—and in the cool halls of the Kunsthalle, he certainly offers a different kind of reality. “His art wants to transcend borders and to explore”, Baden explains of his oeuvre. Hiwa K has lived in Germany since fleeing the Kurdish crisis zone during his twenties. In Iraq, he practiced as a painter for fourteen years: “I stopped making art when I came to Europe. I started to learn flamenco guitar. For me, the beauty of it was the unfolding of questions in the way you see the music of the West (chord based verticality of the western music) and the East (the horizontality melodic based eastern music) meet in Andalusia. I realized I was repeating questions from someone else, but my geopolitical context has different questions. So after seven years, I came back to art to raise these questions in a different way.”

"My geopolitical context has different questions. So after seven years, I came back to art to raise these questions in a different way.”

Today, he creates works across mediums to ask questions about identity, migration, and the social and geopolitical power structures that govern them. The Hector Prize, funded by Hans-Werner Hector, is for artists like Hiwa K who are living in Germany and working in sculpture, and spatial and multimedia installation. “The jury chose Hiwa also because he works so precisely with the sites he shows in,” explains Baden.

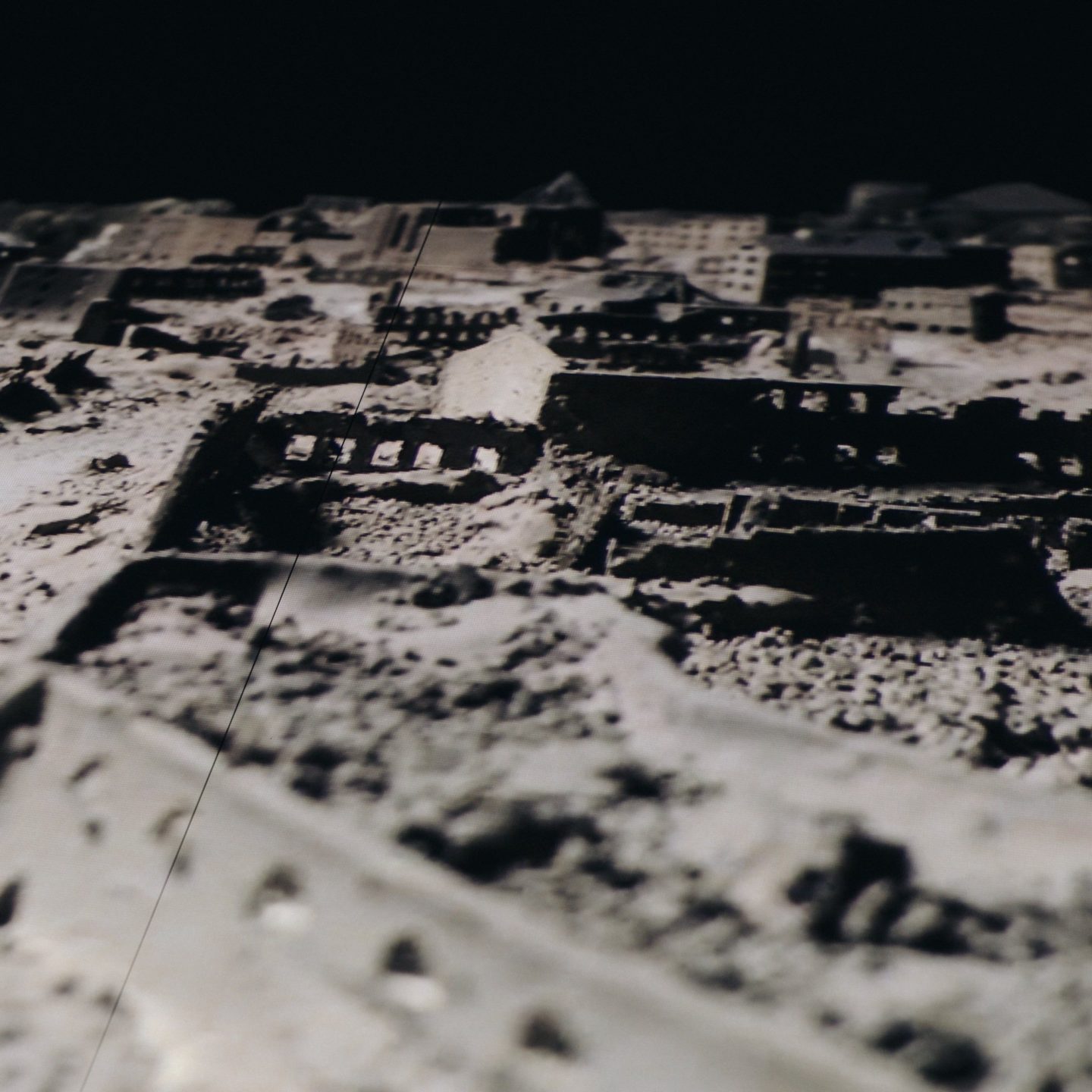

The next room is quiet, it houses ‘Alchemy of Love’ (2019), a work that Hiwa K created for the Hector Prize Exhibition. It is the centerpiece of the show and the secret, dark heart of the spacious new building. The work was inspired by a carpet that Hiwa K and Baden found in the brutalist Collini Center; it depicted Mannheim as it was in the 1960s—a prosperous city. While the dimensions of this carpet are mirrored by ‘Alchemy of Love’; Hiwa K’s message is far darker. The carpet on show at Kunsthalle is printed with an archival photograph of Mannheim from 1943, it shows a post-war city razed almost to the ground. The work has been placed in conversation with Hiwa K’s 2017 video installation ‘View From Above’, created for documenta14, which discusses the perils faced by migrants when fleeing “safe” zones.

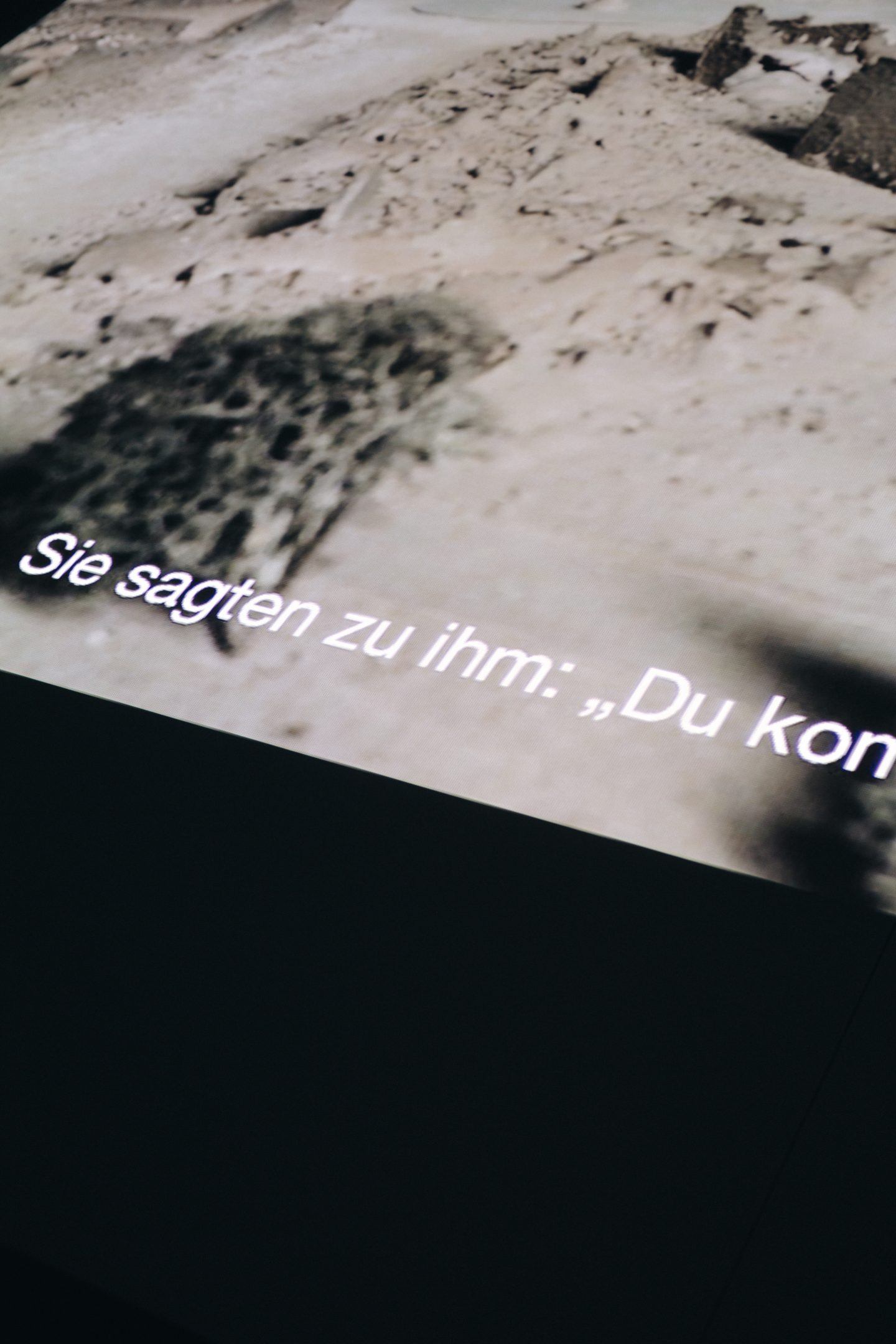

“Every work of Hiwa K is deeply rooted in reality”, Baden explains. His works stem from history and from stories—especially his story. As a conversation partner, Hiwa K is spellbinding, and in his artworks, he uses his narrative power to transform situations and power relations. In his work ‘View From Above’ (2017), Hiwa K tells the story of an anonymous man, who must memorize the plan of a city he has never lived in, in order to be granted asylum by Germany. The film shows images not of Kurdistan or Iraq—the places spoken of by Hiwa K—but rather, of a post-war Kassel, which lies in devastation. Such spaces of crisis are temporary. What is fact and what is fiction, what is justice in the grand narrative of history? In Hiwa K’s art, reality is made up of multiple voices, a polyphony we have to listen carefully to. Perhaps that is why constant movement and music are key to his practice: “We are translating constantly, even in our mother tongue. That’s also what creates space in the works. That’s why I call them unfinished in a way, but that gives life to things,” says Hiwa K.

"Finally, if nothing else works, you just have to go to the heart... I am not esoteric, but I have no other instruments.”

“With this exhibition Hiwa K is on the frontier to something new, challenging the institutional ways of art education”, Baden points out. For Hiwa K, it seems to be something more: “we are entering a new era, we are drowning now”, he says. As temperatures around the world soar, his practice has had to shift—a direct response to climate change, migration and the social and political consequences—namely, the rise of right-wing extremism in Europe—that this increasing heat has engendered. For Hiwa K, words are no longer enough. “First you have to try to change things with your hands, if that does not work you have to use words. Finally, if nothing else works, you just have to go to the heart. We all understand music, vibrations, silence, breathing. I am not esoteric, but I have no other instruments.” Interweaving art with its audience, fact with fiction, and history with the personal, one thing is for sure: Hiwa K’s art is terrifically real.

– This story was produced in collaboration with Kunsthalle Mannheim –

Edited by Rosie Flanagan

All images © Thomas Pirot for IGNANT production