How Does Your Garden Grow? The Latest Exhibition At Gropius Bau In Berlin Explores The Myriad Metaphorical Ways

- Images

- Oliver Tomlinson

- Words

- Rosie Flanagan

In 2019, migratory flows are increasing while borders are tightening. From the safety of our national plots, we watch on as neighboring landscapes burn, waters rise, and boats of people seeking refuge are left to sink. The nursery rhyme ‘Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary’ seems to posit the metaphorical question of the moment: how does your garden grow?

The ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ is an exhibition that ponders the myriad ways in which it does. Set against the neo-Renaissance interior of Berlin’s Gropius Bau—where vines are wrought in iron and golden cornices bloom—twenty artists from around the world offer their interpretations of the garden as a symbol of the complexity and chaos of our time. Drawing its name from Hieronymus Bosch’s famed triptych—a 15th century version of which is part of the show—the exhibition explores paradise, exile, colonialism, migration, and microcosms of place through works by Rashid Johnson, Isabel Lewis, Renato Leotta, Libby Harward, Lungiswa Gqunta, Zheng Bo, Pipilotti Rist, Yayoi Kusama, Maaike Schoorel, Taro Shinoda, and the school of Hieronymus Bosch, amongst others.

Rashid Johnson, ‘Antoine’s Organ’, 2016

At the heart of Gropius Bau is a triple-height atrium where ‘Antoine’s Organ’ (2016), a latticed installation by American artist Rashid Johnson, reaches towards the glass ceiling. The simple but monumental construction is adorned with potted plants, halogen lights, monitors screening loops of Johnson’s past works, shea-butter busts, and books on the history of black communities in America. At the center of this uniquely verdant ecosystem stands a piano; its music helping to communicate Johnson’s discussion of black identity by bringing life to an otherwise silent domestic garden.

Rashid Johnson, ‘Antoine’s Organ’, 2016

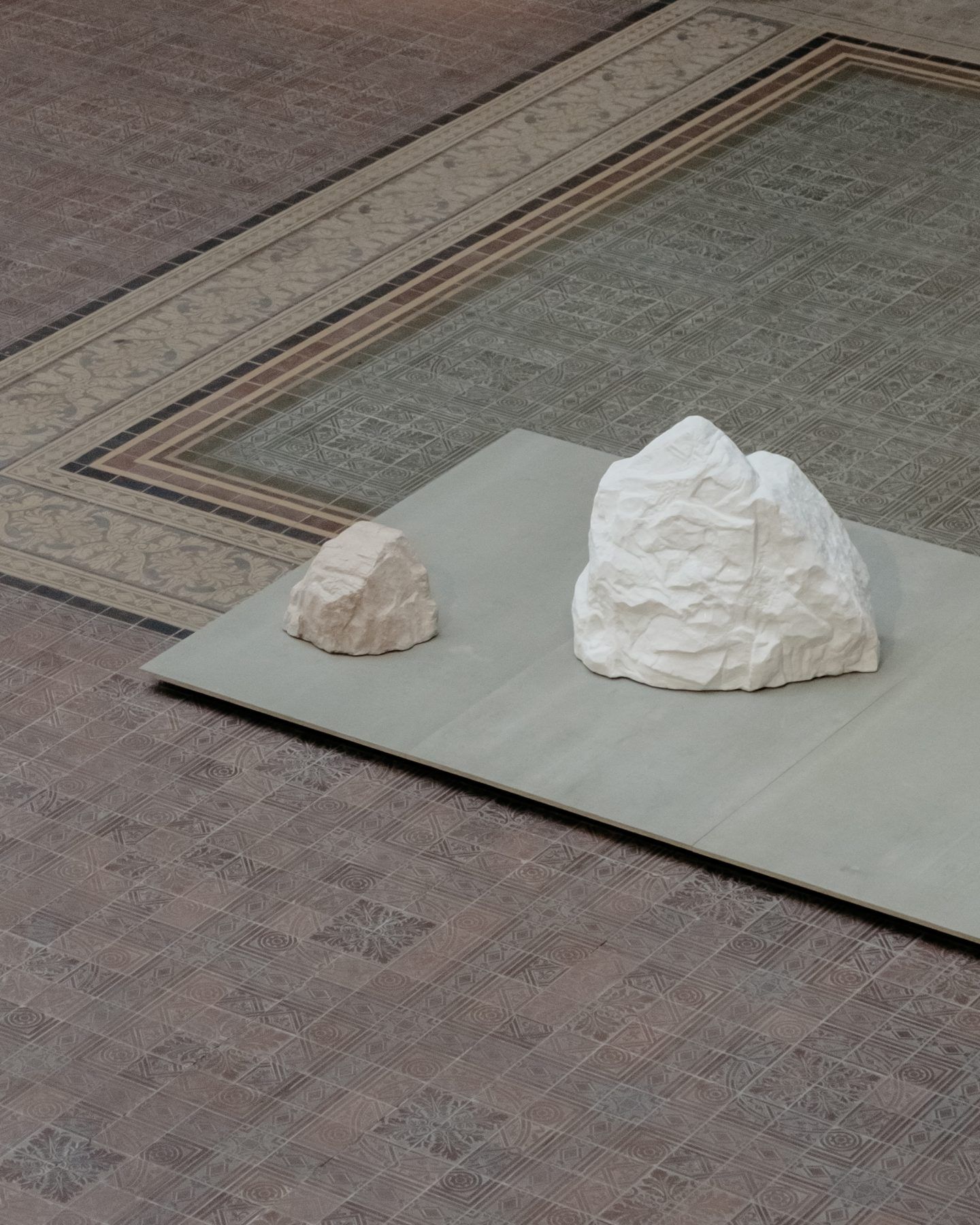

Taro Shinoda, ‘When I see you in the mirror’, 2019

Such sonic activation is an essential element of the exhibition; connecting the various works through sound. Berlin-based performance artist Isabel Lewis was responsible for tuning the space with the help of the musical collective Labour. “For me, the garden is really important in terms of how I think about composition,” she tells us, her voice barely cutting through the sound of the percussionists playing on the second-floor balcony of the atrium. “It’s the conceptual framework for how I work with performance, it’s really what it means to create an immersive fully sensory experience.”

School of Hieronymus Bosch, 'The Garden of Earthly Delights', 1535 to 1550

School of Hieronymus Bosch, 'The Garden of Earthly Delights', 1535 to 1550

In a garden it is almost impossible to separate such sensorial experiences—you don’t just look at things; you move amongst them, you are immersed within them. Inside Gropius Bau, sound allows the exhibition to bloom beyond the artworks, to become an organism that—like a real garden—connects space, object, and visitor. Italian artist Renato Leotta enacts this conceptually; upon entering the corner room that ‘Notte di San Lorenzo’ (2018) occupies, you are asked to remove your shoes and tread lightly. The space has been paved with terracotta tiles that together form a neat square edged in by white floor; producing an aesthetic not dissimilar to that of an Italian courtyard.

Renato Leotta, ‘Notte di San Lorenzo’, 2018

Renato Leotta, ‘Notte di San Lorenzo’, 2018

Created in a small field of lemon trees just outside of Acireale – a Sicilian town that lies between the Mediterranean and Mount Etna, the work poetically transposes an element of the Italian landscape to Berlin. “Very simply, it’s an observation of gravity”, Leotta explains of the work. “It is a record that is part of space, and part of time, which is also a garden”. To create ‘Notte di San Lorenzo’, Leotta lay the unfired clay tiles below the trees in his garden, where, over a period of months, the lemons fell from their branches. The malleable tiles caught the freshness of these full fruits as they dropped, resulting in an abstract map that charts gravity, and what Leotta calls the “negative of a portion of time”. Within the walls of Gropius Bau, Leotta’s work retains the feeling of his garden; offering both sensorial experience and space for quiet contemplation.

Leotta was not the only artist to transfer a garden to a foreign space for the exhibition, though Australian artist Libby Harward’s reiteration of her 2018 work, ‘Ngali Ngariba – We Talk’, does this with far different intent. With a focus on Australia, this site-specific installation and sound work gives voice to plants whose arrival in European gardens occurred through conquest and colonialism. Consequently, the bell jars with perspiring plants hold much more than an organic part of the place that they are from.

As Dr. Glenda Harward-Nalder, an academic who works in tandem with Harward, explains: “First Nation Peoples listen to plants and plants listen to us. Ours is a reciprocal relationship.” In this work, invisible voices speak in the languages of the plants, asking in their mother tongues that we—like Australia’s first people—hear them. “In Gropius Bau Museum, when Gagil [the plant] asks Minyangu ngari gadji? (Why am I here) our Ancestors, who have been waiting nearby for 140 years, will answer, Yuwayi bunji ngali ganyagu wunjayi! (Farewell friend, we are going home now!)”, Harward-Nadler concludes in her essay about ‘Ngali Ngariba – We Talk’. She is referring to the ancestral remains of over 50 Indigenous Australians who—after a long battle—are being returned from German institutions to rest in their homeland this year.

Libby Harward, ‘Ngali Ngariba – We Talk’, 2019

Libby Harward, ‘Ngali Ngariba – We Talk’, 2019

The colonial gardens that Harward’s work speaks of remain political places with rules of entry. South African artist Lungiswa Gqunta’s ‘Lawn I’ (2019) does much to discuss the garden as such a space of exclusion. Inside the room that houses this work, signs of warning reign; this lawn is quite literally dangerous. ‘Lawn I’ consists of a neat square of upturned glass bottles that have been smashed in half, their edges are jagged, and their insides pool with a liquid.

During apartheid in South Africa, only wealthy whites had lawns, and so the garden became symbolic of both privilege and suffering. “These markers are a constant reminder of the racial oppression of black South Africans forced to work tirelessly with little pay, to maintain and nurture the very spaces they will never get to enjoy” Gqunta explains. Around the world, broken bottles and glass similar to those used by Gqunta are cemented into the top of garden fences to deter unwanted visitors. How does your colonial garden grow? Through disenfranchising some, and disallowing others.

Lungiswa Gqunta, ‘Lawn I’, 2019

Lungiswa Gqunta, ‘Lawn I’, 2019

Hong Kong-based artist Zheng Bo presents four works from 2018 that look at such questions of deprivation from an eco-queer perspective. In ‘Fern as Method’, ‘Movements’, and ‘Survival Manual II (Hand-Copied 1945 “Taiwan’s Wild Edible Plants”)’, Bo makes a bid for what he terms a “Good Anthropocene” by illustrating the benefits of decentralizing human beings in favor of a multispecies future. His video work ‘Pteridophilia 1-4’, in which young men engage in sexual activities and BDSM with plants, appears to make a pointed comment on nature’s inability to consent or object to mankind’s needs and desires.

Zheng Bo, 'Pteridophilia 1-4', 2016–2019; 'Movements', 2016; 'Fern as Method', 2019

Zheng Bo, 'Fern as Method', 2019

In Pipilotti Rist’s ‘Homo Sapiens Sapiens’ (2005), lust also takes center stage. Like the Garden of Eden, the utopian space is broken and remade through seduction. The Swiss artist’s immersive video work is viewed from the floor, where floor pillows in acid green and orange offer an undulating space for bodies to fall. An oval-shaped screen shows peaches and testicles being massaged at intervals while strange sounds hum in the background. While Rist’s work is purely paradisiacal, Yayoi Kusama’s ‘With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever’ (2013–2019) is a comment on the symbiosis of utopia and dystopia, and our ability to discern one from the other. In a white space adorned by the multi-colored spots of Kusama’s fame, three oversized tulips bloom. But what first appears playful quickly becomes sinister as the mono-visual nature of object and space cause the visual collapse of the room: is this truly paradise?

Yayoi Kusama, ‘With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever’, 2013–2019

Yayoi Kusama, ‘With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever’, 2013–2019

Yayoi Kusama, ‘With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever’, 2013–2019

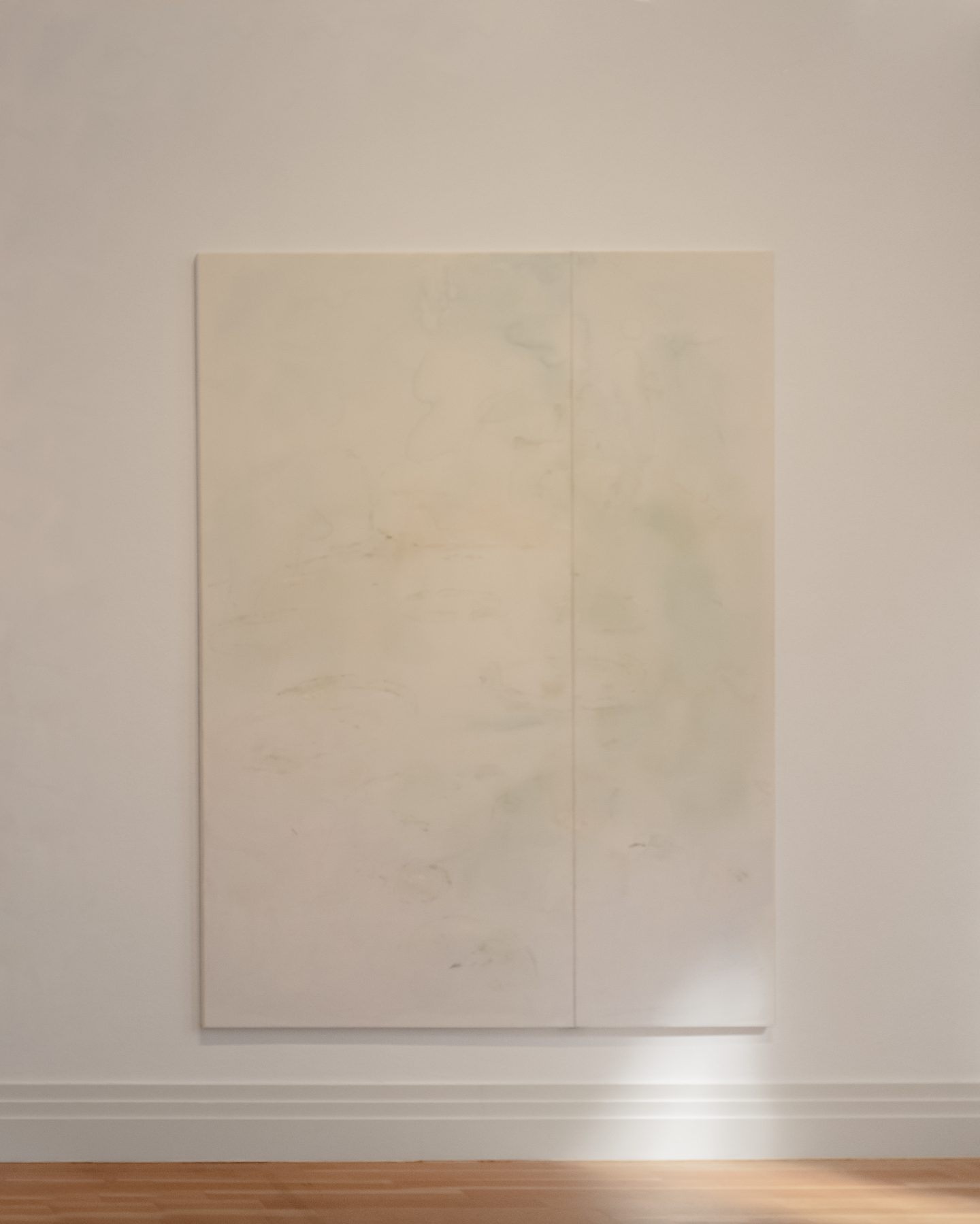

The changeable nature of a garden is explored differently through the work of London-based artist Maaike Schoorel: “Gardens are in flux,” she explains, “depending on the light, a garden changes constantly.” Her abstract paintings are gestural; texture and color work together on the large canvases to create the experience of looking at a garden. “A brushstroke from the edge of a stem moves upwards and touches on a different texture of the leaf of a flower,” she explains. “These marks together in its context of the space form the shape of a flower within the garden.”

Maaike Schoorel, 2019

Maaike Schoorel, 2019

Taro Shinoda, ‘When I see you in the mirror’, 2019

Taro Shinoda, ‘When I see you in the mirror’, 2019

Such formal consideration and deliberate abstraction are equally important in Japanese artist Taro Shinoda’s ‘When I see you in the mirror’ (2019). In this work, Shinoda examines the garden as a structure for thought, creating from marble stones that mimic those that would be found in Japanese rock garden—a space specifically designed as an imitation of nature, to allow space for meditation and clarity of thought. “I believe that people can only understand the world through the lens of abstraction,” he explains. “The garden is an abstraction of nature, and thereby like a means to relate to the world. In effect, the garden helps you to think,” he concludes; a fitting explanation of the exhibition in its entirety.

All images © Oliver Tomlinson for IGNANT