Robert Irwin’s Luminescence Shines In Berlin, With Light And Space (Kraftwerk Berlin)

- Name

- Robert Irwin

- Project

- Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin)

- Images

- Timo Ohler

- Words

- Steph Wade

The seminal contemporary American artist Robert Irwin’s latest installation, ‘Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin)’, is a mammoth work of art exploring human perception. IGNANT has partnered with LAS (Light Art Space) to present this immersive experience of light, space, and form, set against an awe-inspiring Brutalist backdrop in the iconic former power plant, Kraftwerk Berlin.

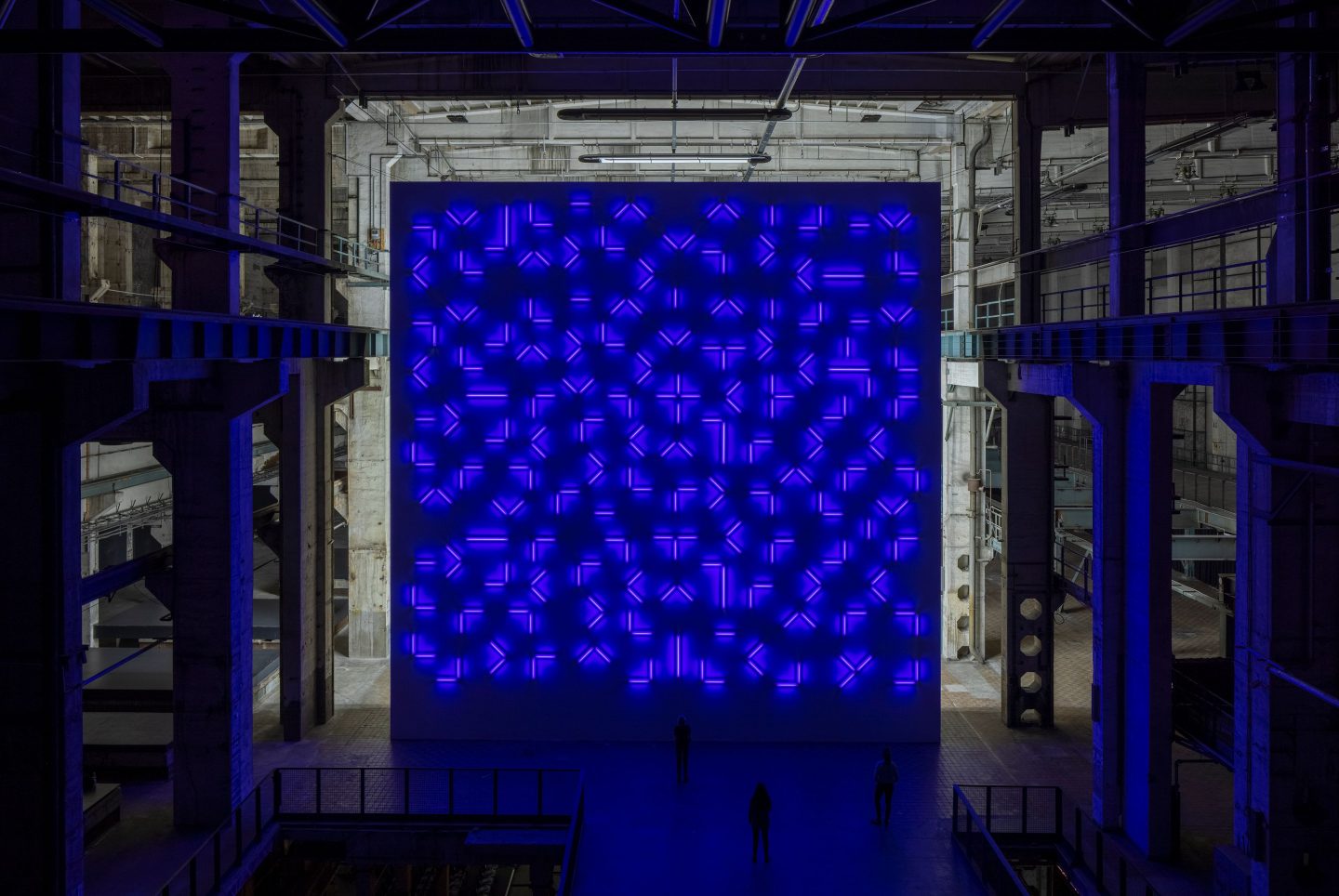

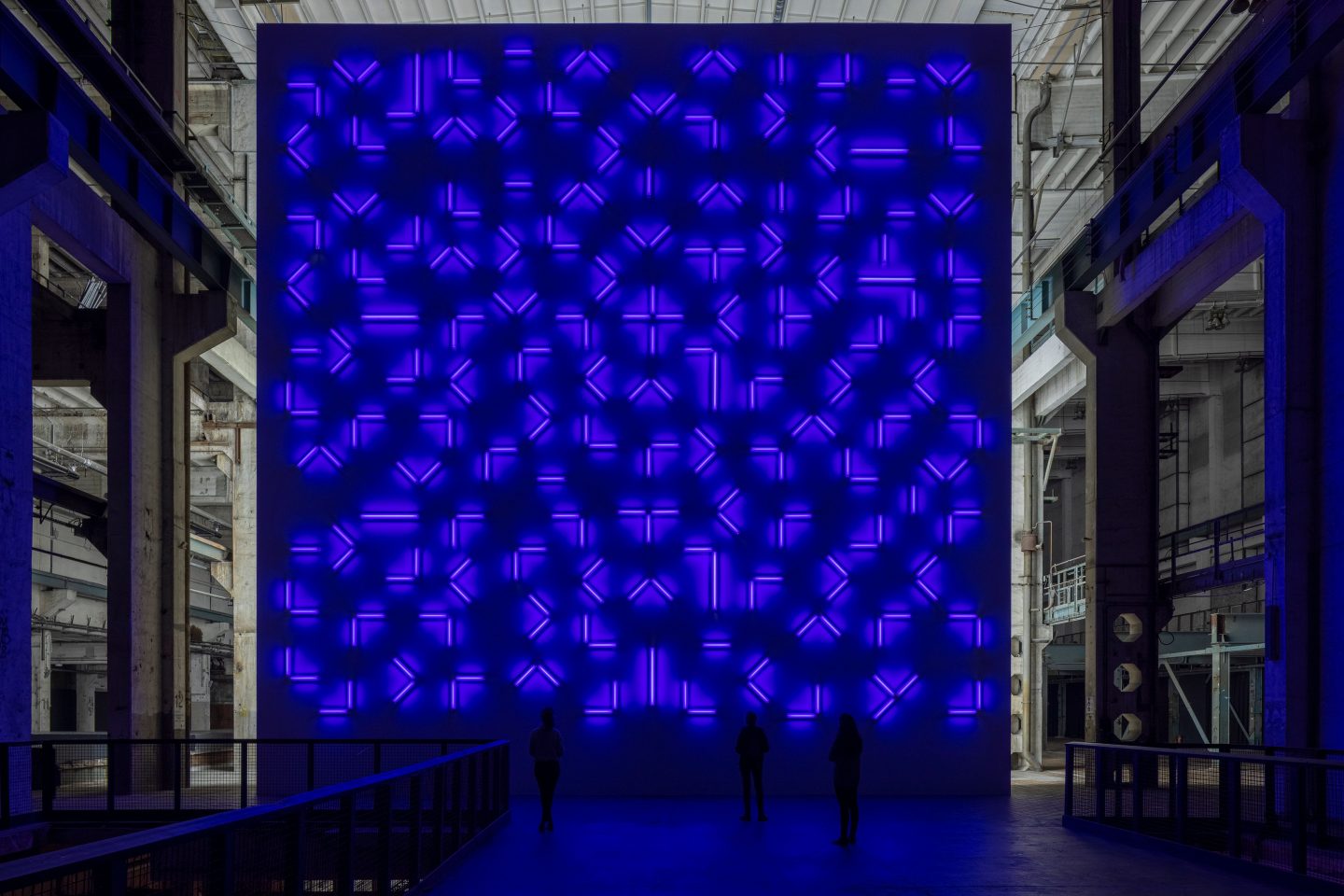

The exhibition showcases a visionary new work by Irwin, who is 93 years of age—a freestanding 16 by 16 meter wall lined on either side with hundreds of fluorescent tubes illuminating the venue’s 100-meter-long turbine hall. The installation, created especially for Kraftwerk Berlin, continues Irwin’s series of works Light and Space which he began almost fifteen years ago, and is the largest work of art that the artist has ever exhibited in Europe. The piece keeps in line with the Southern Californian art movement called Light and Space, in which perception itself is the medium—it originated in the 1960s and was made famous by Irwin and other artists like James Turrell, who is a close friend and artistic collaborator of Irwin’s. Together, over the years the pair has experimented with light greatly, using it to alter the way we perceive our surroundings. Like Turrell, much of Irwin’s work lies in creating a phenomenon for people where, when viewing his work, it is almost impossible to differentiate between seeing and imagining.

“My ambition is, in a sense, to make you see a little bit more tomorrow than you saw today”

With this in mind, the commission for this piece first started as a dialog between the artist and the art foundation LAS, to create an all-encompassing experience of perception where light, space, color, and form blend together to defy visual logic. Since the 1970s, Irwin has produced exclusively site-specific works—so the earliest discussions LAS and Irwin had were in relation to the qualities of the site itself, and how the piece could stand in contrast to the interior of the imposing, decommissioned power plant. The venue is situated on the border of the Kreuzberg and Mitte neighborhoods, and was once used to power all of East Berlin—The Berlin Wall stood very close by, with other historical landmarks including Checkpoint Charlie and the Brandenburg Gate also not far away.

For Irwin to create the new piece, the location meant everything: and with the site in particular he was struck by the scale and drama of the upper turbine hall. To work successfully with the space he would first need to meet the challenge of its impressive scale: “That’s what site-conditioned means,” Irwin explained to LAS. “You start with the site and its characteristics, and you try to match them in a way that enhances the experience.”

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

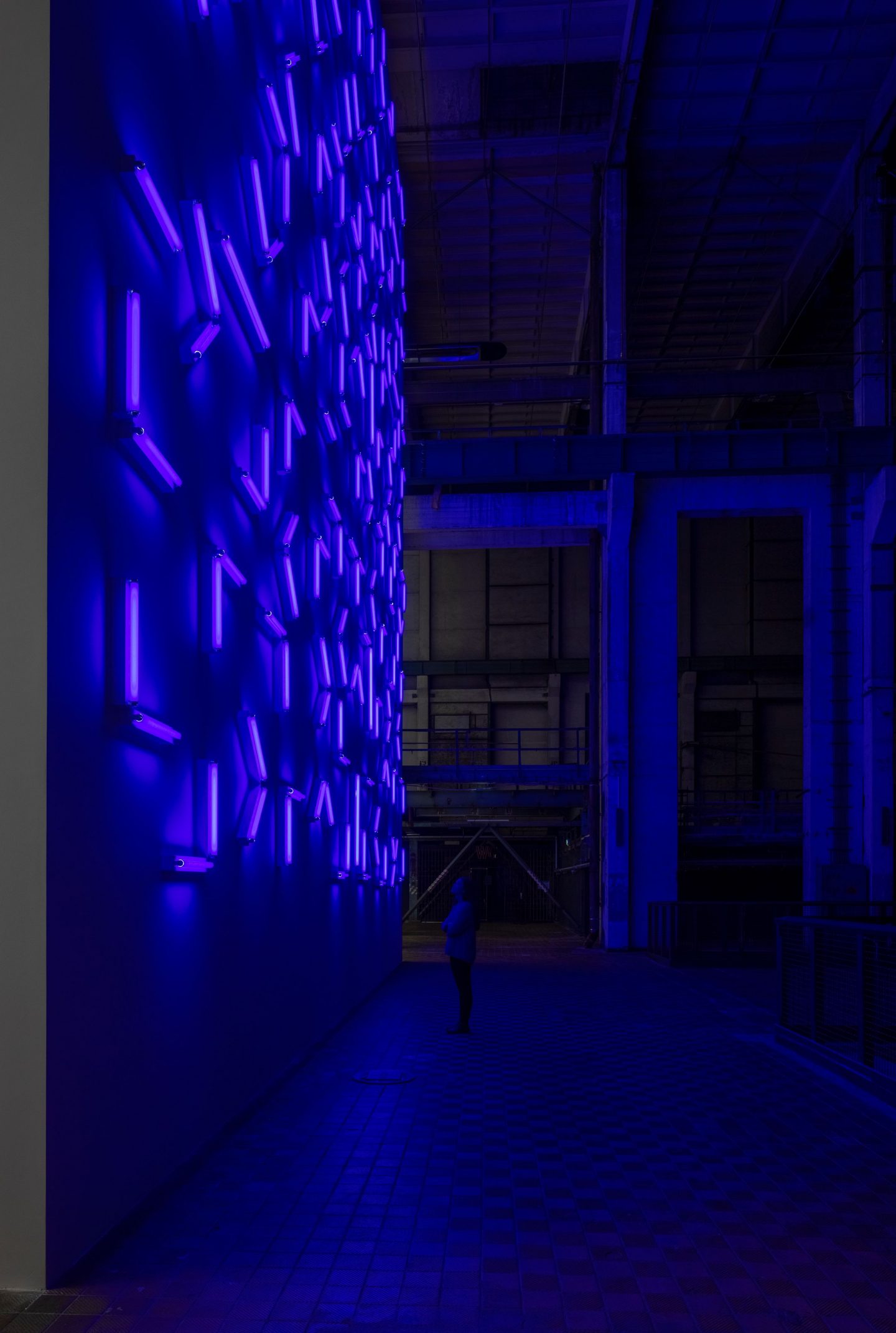

Upon first impression, there are many aspects of the work that strike the eye: its size, no doubt, which when standing close by is staggeringly high; its color—fluorescent white on one side and cobalt blue on the other; and its position in the space itself, a multilevel industrial complex dominated by cast-concrete pillars, ceilings, and floors, with metal railings, pipes, and electrical conduits. Walking through the first lower hall, one walks past a series of enormous structural beams, and up a switchback staircase to the upper hall, with its soaring high ceiling that reaches more than twenty meters in height. This area is flanked by mezzanine-like spaces with suspended steel walkways: it is an architectural maze of sorts, and perfect fodder for Irwin’s piece to shine—both literally and metaphorically.

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

Much of Irwin’s work lies in creating a phenomenon where it is almost impossible to differentiate between seeing and imagining

In Berlin, a city known for its cultural landscape that promotes a range of experiential moments through art, design, architecture, music, and performance, venues like power plants, factories, and churches seem as if they are built (beyond their original function) to house experiences for altered states of being. Just look at the infamous Berghain and Tresor nightclubs, or König Gallery’s past life as a 1960s Brutalist church.

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

Speaking of former identities, Irwin himself was not always immersed in the world of light and space. At the start of what would end up being a prolific, six-decade career, Irwin’s practice first was rooted in early Abstract Expressionism. Back in those first years as an abstract expressionist painter in the 1950s, one day Irwin realized his paintings were not giving him meaning. “I had my first show in a major gallery, and there was that moment before everyone came in that I realized everything I was doing was shit,” he says, in a rare short film created by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

Galvanized by this realization, Irwin moved through observation-based Minimalist painting, sculpture, and wall-objects in the 1960s, yet it wasn’t until the 1970s that the artist abandoned his object-centric practice altogether, in favor of working more with fluorescent light. He spent time researching the science of perception with Turrell, and debated with NASA scientists on the potential of human habitability in space, all the while creating luminous pieces with either natural or artificial light—not out of any sculptural desire, but rather for the effect the works could have on the visitor’s awareness. In the piece currently on show, the way Irwin distributes the fluorescent tubes is based on two overlapping geometries: one set are vertical and horizontal, the other are rotated on a 45-degree angle. There is something fuzzy and magnetic about their repetition that is reminiscent of the Matrix code, or how electricity might look materialized (albeit in artistic form). This resonance with electricity comes full circle then, almost as an irony for Irwin’s takeover in a space that once buzzed with real electromagnetic energy.

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

“My ambition is, in a sense, to make you see a little bit more tomorrow than you saw today,” Irwin said to Milton Esterow, in “How Public Art Becomes A Political Hot Potato,” in January 1986. This comment is demonstrative of his interest in what occurs for the viewer once the artwork is left behind. With ‘Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin)’ this ambition continues—Irwin’s ability to convey a powerful show of light, color, and space as a sensory experience is one that leaves a lasting and widened impression.

Robert Irwin, Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) , 2021. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). © Photo: Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.

Robert Irwin’s Light and Space (Kraftwerk Berlin) is on show until January 30, 2022 at Kraftwerk Berlin. For more information, click here.

Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space). All images © Timo Ohler. VG Bild-Kunst, 2021.